полная версия

полная версияRalph Gurney's Oil Speculation

Otis James

Ralph Gurney's Oil Speculation

CHAPTER I.

THE "CHUMS."

The puffing, panting engine that dragged the long train of heavy cars into the busy little city of Bradford, in the State of Pennsylvania, one day last summer, witnessed through its one white, staring eye, sometimes called the head-light, many happy meetings between waiting and coming friends; but none was more hearty than that between two college mates – one who had graduated the year previous, and the other who hoped to carry off the honors at the close of the next term.

"Here at last!" exclaimed George Harnett, as he met his old chum with a hearty clasp of the hand. "In this case, if the hope had been much longer deferred, the heart would indeed have been sick."

"It was thoughtless in me, old fellow, not to have sent you word when I concluded to remain at home two days longer, but the fact of the matter is that I did not think you would be at the depot to meet me, but would let me hunt you up, for I suppose you do have some kind of an office."

"Yes," laughed the young man, "I have an office; but since my work just now is several miles from here, I am seldom at home, and was obliged to come for you, or run the chance of having you spend a good portion of your vacation hunting for me."

"And are you sorry yet that you chose civil engineering for a profession?"

"Sorry! Not a bit of it! Up here there is more excitement to it than you are aware of, and before you have finished your vacation, you will say that the life of a civil engineer in the oil fields of Pennsylvania is not by any means monotonous. But come this way. My team is here, and while we are talking we may as well be riding, for we have quite a little journey yet before us, over roads so bad, that you can form no idea of them by even the most vivid description."

"But I thought you lived here in Bradford."

"I live where my work is, my boy, and since it happens just now to be out of town, my home, for the time being, is in as old and comfortable a farm-house as city-weary mortals could ask for."

"Well, I can't say that I shall be sorry to live in the country – for awhile, at least."

"Sorry! Well, I hardly think you will be, when you learn what I have to offer you in the way of enjoyment. I am locating some oil-producing lands, in a valley where game is abundant, where the fish prefer an artificial fly to a natural one, and where the moonlighter revels with his harmless-looking but decidedly dangerous nitro-glycerine cartridge."

"What do you mean by moonlighter?" asked Ralph, as he seated himself in the mud-bespattered carriage which George pointed out as his.

"A moonlighter is one who shoots an oil well regardless of patent rights or those owning them, save when, by chance, he finds himself gathered in by the strong arm of the law."

"I thank you, Brother Harnett, for your decidedly clear explanation. I almost fancy that I know as much about moonlighters now as when I asked the question, which is saying a good deal, for you very often contrive, in explaining anything, to leave one even more ignorant than when he consulted you."

"If you are willing to listen to as long and as dry a dissertation on oil wells in general, and illegally-opened ones in particular, as ever Professor Gardner favored us with on topics in which we were not much interested, I will begin, stopping now and then only to prevent my teeth from being shaken out of my head as we ride over this road."

The two had hardly got out of the "city," and the thoroughly bad character of the road was already apparent. Riding over it was very much like sailing in a small boat on rough water – always down by the head or up by the stern, but seldom on an even keel.

"Go on with the lecture," said Ralph, "and while I try to hold myself in the carriage, I will listen."

"Because of my friendship for you. I will make it as brief as possible. In the first place, you must know that before oil is struck, the operator finds either a rock formed of sand or of gravel. This is the strata just above the deposit of petroleum.

"Of course this must be bored through, if possible, and in the pebbly rock there is no trouble about it. The drills will go through, and the gravel will be forced to the surface without much difficulty. But when the sand-rock is met, it clogs the drills, making it almost impossible to bore through. A heavy charge of nitro-glycerine makes short work of this rock, and out comes the oil.

"Now, this method of blasting in oil wells has been patented, or, at least, the cases for the glycerine and the manner of exploding it has, and the company, which has its office in Bradford, use every effort to discover infringements of their patent. Like all owners of patent rights, they charge an extra price for their wares, and the result is that there are parties who will, for a much smaller amount of money, shoot a well and infringe the patent at the same time. These people are called moonlighters, and the risk they run of losing their lives or their liberty is, to say the least, very great. The lecture-hour has now been fully, and I hope I may say profitably, employed."

"If it profits one to learn of your friends, the moonlighters, then your lecture has been a success. But how do you find excitement in anything they do? Surely they do not make public their unlawful doings."

"Oh, everything save the shooting of the well is done legally, and with many even that is questionable! The cases are to be tried, and many believe that the owners of the patent have really no rights in the premises. The owners or prospective owners of the land whereon the wells are to be sunk, employ me to survey their tracts, and by that means I frequently make the acquaintance of those people who, for the almighty dollar, will peril their lives driving around the country with nitro-glycerine enough to blow an entire town up."

"Let me trespass once more on you for dry detail, and then I will learn anything else I may want to know from observation. What is nitro-glycerine?"

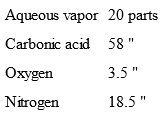

"I will answer your question by quoting as nearly as I can from what I read the other day. It is composed of:

"Until 1864 it found no practical application, except as a homeopathic remedy for headache, similar to those which it causes. In that year, Alfred Nobel, a Swede, of Hamburg, began its manufacture on a large scale, and, though he sacrificed a brother to the terrible agent he had created, he persevered until in its later and safer forms nitro-glycerine has come into wide use and popularity. It is a clear, oily, colorless, odorless, and slightly sweet liquid, and can, with safety, only be poured into some running stream if one wishes to be rid of it. Through the pores of the skin, or in the stomach, even in small quantities, this oil causes a terrible headache and colic, while headaches also result from inhaling the gases of its combustion. It has thirteen times the force of gunpowder, exploding so much more suddenly than that agent does, that in reality it is much more powerful, and it is this same rapid explosive power that prevents it from being used in fire-arms."

"You would make a first-rate professor, George," said Ralph, laughing, "and you may refer to me in case you should desire to procure such a position. Now I think I am armed with sufficient knowledge to be able to meet your oily friends, the moonlighters, and have some idea of what they mean when they speak."

"If I am not mistaken we shall meet some of them very soon, without trying hard; but if we do not, I will take you to one of their cabins as soon as we may both feel inclined to go."

"Don't think that I have come here to spend my vacation simply with the idea that I am at liberty to make drafts at sight on your time," replied Ralph, as an unusually rough portion of the road necessitated his exerting all his strength to prevent being thrown out of the wagon. "I intend to be of every possible assistance to you, and when I cannot do that, if you are still obliged to labor, I will extract no small amount of enjoyment out of your farm-house and its surroundings. But at any time that you have a few hours to spare, I will be only too well pleased to meet with any adventure, from nitro-glycerine blasts to the perils of trout-fishing."

By this time the conversation ceased, owing to Ralph's interest in the scenery around him, and the curious combination of oil-tanks and derricks with which the landscape was profusely dotted. From Bradford to Sawyer the road winds along at the base of the hills through a lovely valley, that seems entirely given over to machinery for the production and storage of oil. On every hand are the tall, unsightly constructions of timber that form the derricks, looking not unlike enormous spiders, as they stand on the sides of the mountains or in the ravines, while the network of iron pipes, through which the oil is forced by steam-pumps from the wells to Jersey City, are fitting webs for such spiders.

Huge iron tanks, capable of holding from twenty to forty thousand barrels of oil, dot the valley quite as thickly as do the blots of ink on a school-boy's first composition, and form storage places for this strange product of earth, when the supply is greater than the demand. It is truly a singular scene, and he who visits this portion of the country for the first time cannot rid himself of the impression that he has, by some mysterious combination of circumstances, been transported to some remote and unknown portion of the globe.

George, to whom this scene was perfectly familiar, did not seem inclined to allow his friend to remain in silent wonder, for he persisted in supplying him with a fund of dry detail, which effectually prevented any indulgence of day-dreams.

Although Ralph would have preferred to gaze about him in silence, George told him of the Pipe-Line Company, who owned the greater portion of the huge iron receptacles for oil; who also owned the network of iron pipes, through which they forced the oil to the market at a charge of twenty-five cents per barrel.

He also told him that this company connected the main line of pipes with each tank owned by the oil producers, supplying a small steam-pump at each connection, and, at stated times, drew off from private tanks the oil. He even went into the particulars of the work, explaining how each man could tell exactly the number of barrels the company had taken from his tank by measuring the depth of the oil before and after the drawing-off process.

Then he described how these huge receptacles were frequently struck by lightning, setting fire to the inflammable liquid, and causing consternation everywhere in the valley; of the firing of solid shot into the base of the tanks to make a perforation that would allow the oil to run off, and of the loss of property and danger of life attending such catastrophes.

So much of dry detail or interesting particulars of the oil business had the young engineer to tell, that he had hardly finished when the horses turned sharply into a narrow road, over which the trees formed a perfect archway, that led to just such a farm-house as suggests by outside appearance all the good things and comforts of life.

"This is to be home to you for a while," said George, breaking off abruptly in his dissertation on the price and quality of oil, in which Ralph was not very much interested, "and I can safely guarantee it to be a place which you will be sorry to leave after once knowing it."

"It certainly does not seem to be a place around which anything exciting can be found," thought Ralph; but, since it was only rest from study he was in search of, he was content with that which he saw.

CHAPTER II.

A NEW ACQUAINTANCE

Ralph Gurney was one who thoroughly enjoyed everything in which pleasure could be found, and even while George was caring for his horses, of which he was very fond, Ralph had already begun a survey of the farm on which he was to spend his vacation.

The cattle, poultry, horses, dogs, and even the cat, had received some attention from him, and he was on his way to the sheep-pasture near by to make the acquaintance of the woolly members of the flock, when the sharp ping of a bullet was heard as it whistled by his head, while, a second later, the report of a rifle rang out sharply.

There was something so entirely unexpected and so thoroughly startling in this mode of salutation in so peaceful a place, that Ralph leaped two or three feet in his fright, and at the same time saw the hole in the brim of his hat, which showed how near the deadly missile had come to him.

Almost any one would be alarmed at such a visitor, even though he might have been expecting this attention, and Ralph came very near trembling with fear as he realized how narrow had been his escape from death.

He looked quickly around to see who was using him as a target; but no one was in sight. The sheep had been quite as much startled by the report as he had by the proximity of the bullet; therefore, there was no reason to suspect that they had had anything to do with this decided frightening of the new boarder.

Ralph was on the point of calling out to George for an explanation of this apparently reckless shooting, when a voice from amid a small clump of trees shouted:

"Hold out your hat and I will put a bullet through the center of it."

Even if Ralph had not been angry because of the danger he had been forced to run, he would not have accepted any such cheerful invitation, and, instead of replying, he looked carefully around in search of the speaker.

"Hold out your hat, and I will show you what I can do," continued the voice, while its owner persistently remained hidden.

"I don't know who you are," said Ralph, speaking sharply; "but from what I have already seen of your reckless shooting, I consider it to be some one's duty to teach you how to handle fire-arms."

"And you propose to do it, eh?" was the question, as a boy eighteen or nineteen years of age, with a face that was the perfect picture of good humor, walked out of the thicket. On his shoulder he carried a rifle, and in his left hand some partridges and a fox-skin. "That was a nasty shave for you," he continued, in a half-apologetic tone; "but, you see, I hadn't any idea there was any one around. Farmer Kenniston is down on the meadow, and Harnett went to town this morning; so you see that, by rights, you ought not have been here."

"And because, in your opinion, I should have been somewhere else, you concluded to send me away by the most certain and effectual method?" asked Ralph, having by no means subdued his anger, although it was vanishing quite rapidly before the pleasant tone and face of the boy who had come so near killing him.

"Well, you see, I didn't know you or any one else was within a mile of the place. I had a charge left in my rifle, and I wanted to see if I could knock a knot out of that second board in the barn. Just as I pulled the trigger, you came from behind the shed, and then I couldn't call the bullet back. I am sorry that I startled you so, and I was in hopes you would hold out your hat, so that you could have seen how handy I am with a rifle, which would have made you feel easier."

"I must confess that I can't understand how I could be soothed by any proof of your skill as a marksman," replied Ralph, with a smile, his anger now almost completely gone. "Of course, I know that you didn't intend to shoot so near me; but in the future I advise you to empty your rifle before you come so near to a house."

"But I have wanted to put a bullet into that knot from the trees back there ever since I have been here, and now let's see if I struck it fairly."

As if he considered that he had made all necessary apologies for the shot which had startled Ralph, the boy started towards the barn, and in another instant he was pointing triumphantly to the offending knot in the board, which had been completely shattered by the bullet.

"There!" he cried. "Harnett said I couldn't hit it from that dead pine tree, and that even if I did succeed in hitting it, I couldn't split it. Now we'll see what he has got to say to that."

Ralph had nothing to say as to the argument between his friend and the stranger, and in the absence of anything else to say, he asked:

"Do you live here?"

"I am living here just now, and shall for some weeks longer, I suppose. You are Ralph Gurney, whom Harnett has been expecting, I fancy?"

"Yes; but if George has told you who I am in advance of my coming, he has not been so liberal to me in regard to yourself."

"That probably arose from the fact that I am no one in particular, while, on the contrary, you are to become one of the particularly bright and shining lights in the medical world. I am only Bob Hubbard."

Who Bob Hubbard might be Ralph had no idea; but even though the young gentleman spoke of himself in such a deprecating way, it was easy to see that he did not consider himself of slight consequence in the world. He was a bright, jovial, generous looking boy, with a certain air about him which made the shot, fired so dangerously near Ralph, seem just such a reckless act as might be expected of him.

"Do you like hunting and fishing?" he asked, after he found that Ralph was not disposed to say anything about the profession of medicine he had chosen, and which George had evidently spoken of.

"Indeed I do," was the decided reply. "Is there much sport around here?"

"All you want. I have only been out about two hours, and I have got these," he said, as he held up his game. "And as for fishing, you can catch trout until your arms ache – providing they bite rapidly enough."

"Indeed!" replied Ralph, dryly. "I fancy I have seen as good almost anywhere. Do you go fishing very often?"

"Nearly every day."

"Then, if George has any business to attend to this afternoon, suppose you and I see if the fish will bite fast enough to make our arms ache pulling them in."

Bob hesitated in what Ralph thought a very peculiar way, and said, after a pause of some moments:

"I'd like to, but I have an important engagement this afternoon, and I hardly see how I can arrange it."

There was certainly nothing singular in his not being at liberty to accept the proposition made so suddenly, and Ralph would have thought his refusal the most natural thing in the world had it not been for his evident embarrassment when none seemed reasonable. However, the young pleasure-seeker attached no importance to what seemed like singular behavior on the part of this newly-made acquaintance, and was about to make another proposition for a fishing excursion, when Harnett suddenly made his appearance.

"Hello, Bob!" he cried, "you've been making the acquaintance of my chum, have you?"

"Yes, after a fashion. I fired at that knot in the barn you said I couldn't hit from the pine tree, and came near putting a bullet through his head. But I hit the knot, and what's more, I split it."

"And here is a hole in the brim of my hat, to prove that he did fire at it," said Ralph, laughing, as he held up his perforated hat to display the mark of the bullet.

Harnett looked with no small degree of alarm at the evidence of Bob's shooting, and said, sternly:

"I think it is quite time that you became a trifle more careful with your fire-arms, Bob. You have already had several narrow escapes, and will end by killing some one, if you don't stop shooting at every promising mark you see."

"I'm not half as careless as I might be," said Bob, earnestly. "This is the first time that I have ever really come near hurting any one."

"What about the time when you came near hitting Farmer Kenniston, and killed a lamb? Have you forgotten the untimely death of Mrs. Kenniston's favorite duck, or your adventure with the red calf in the pasture?"

"Oh, those don't count – at least none except the lamb scrape are worth talking about, Harnett, so don't read me one of your long-winded lectures; and, now that I have hit the knot in the barn, I promise not to shoot at anything within half a mile of the place. I'm going down to town for a while, and when I get through with what I have on hand, we'll make some arrangement to show your friend the oil region."

As he spoke Bob went into the stables, and when the two friends were alone again, George asked:

"Well, Ralph, how do you like what you have seen of the moonlighters? Not very ferocious, eh?"

"What do you mean? I haven't seen any moonlighters yet."

"Indeed! You have been talking for the last ten minutes with the most successful of them. Bob Hubbard enjoys the rather questionable distinction of being the most noted one in this section of the country."

Ralph looked at his friend in speechless astonishment for several minutes; this careless, good-natured boy was very far from being the famous moonlighter his fancy had conjured up, and it is barely possible that he was disappointed at not having seen some more savage looking party, for he had speculated considerably about these people who explode nitro-glycerine in an illegal manner.

"If I am not mistaken," continued Harnett, "he is going to shoot a well to-night, and I guess there will be no difficulty in getting his consent for you to be present. Wait here, and I will talk with him."

George hurried away toward the stables, leaving Ralph in a curious condition of mingled wonder and surprise that in this very peaceful-looking place there could be found such an evident fund for adventure.

The gaining of Bob's consent for Ralph to be present at the shooting of the well was not such a difficult matter, judging from the very short time George found it necessary to talk with him. When Harnett came from the stable, he told Ralph that the necessary permission had been given, and that they would start for the cabin of the moonlighters at once, in order that none of the details of the work might be lost.

While they were speaking, Bob drove out of the stable behind a pair of small gray horses, which were so spirited that their driver could pay no attention to anything but them.

"I'll see you again very soon," he shouted; and hardly had he uttered the words before he was tearing along the rough road at a rate of speed that threatened a rapid dissolution of the light carriage.

If George had any business to attend to on that day, he evidently made up his mind to neglect it, for he began to make his arrangements for the journey with quite as much eagerness and zest as displayed by Ralph.

Since it was by no means certain that the well would be opened that night, owing to the vigilance of the owners of the torpedo patent, George made preparations to remain away from Farmer Kenniston's all night, taking blankets, food, fishing-tackle and rifles, as if their excursion was to be one simply of a sporting nature.

"It wouldn't do for us to drive out to the moonlighters' cabin as if we were going to see a well shot," he said, in reply to Ralph's questions of what he proposed doing with rifles and fishing-rods; "for, if we were seen, it would be quickly reported in town, and Bob would have the whole posse of Roberts Brothers' force upon him. Now, there would be nothing thought of our going out fishing, which fully accounts for my preparations. I have known Bob to wait for a week before he dared explode a charge, and I don't care to get mixed up in any encounter between these two sets of torpedo men."

"I don't want any harm to come to him through me," replied Ralph, gleefully, "but I should not be at all sorry to see just a little excitement in the way of a chase of the moonlighters."

"There is every chance that you will be fully satisfied before you leave this portion of the country," said George, grimly; and then, as his horses were ready for the road once more, he added: "Get in, and, if nothing happens, I will show you the cabin of the moonlighters in less than an hour."

CHAPTER III.

THE CABIN OF THE MOONLIGHTERS

Bob Hubbard had been away from the Kenniston farm-house nearly half an hour when Ralph and George left it, but the latter was so well acquainted with the country that he did not need any guide to the cabin, and could not have had one, had he so desired, for Bob was far too cautious to be seen leading any one to his base of operations.