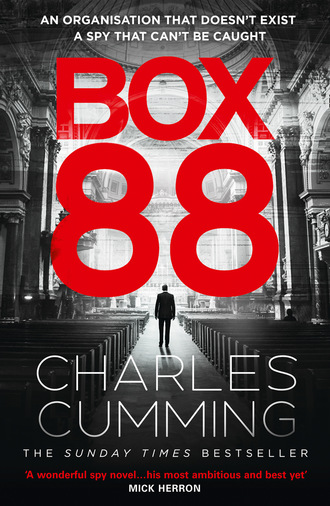

Box 88

‘How did you meet Xavier?’ de Paul asked, accepting an Order of Service from a good-looking man in his twenties who looked as though he’d walked straight off the set of Four Weddings and a Funeral.

‘Out in South Africa,’ she said.

‘I see,’ he replied, absorbing the euphemism.

One of the mourners passed de Paul and touched him on the back, saying only: ‘Cosmo’ in a low murmur before settling into a pew. Cara told de Paul that she would prefer to be alone ‘at this difficult time’ and was glad to see him take the hint.

‘Of course. It was charming to meet you.’

‘Likewise,’ she said, and moved quickly along the nave.

She was staggered by the opulence of the church. Tessa’s research into the Bonnard family had revealed that Xavier’s mother, Rosamund, was the daughter of a duke whose family appeared to have owned, at one time or another, most of the land between Cambridge and Northampton. Perhaps it took that kind of old school clout to secure the entirety of Brompton Oratory for a midweek funeral. Certainly it looked as though the church was going to be three-quarters full. There were already at least four hundred people filling the pews and many more still shuffling in through the entrance. Cara stopped halfway along the aisle and turned to look for Kite. To her astonishment she saw him immediately, standing no more than ten feet away beneath a sculpture of St Matthew. It was the first time that anyone on the team had been that close to BIRD. She was struck by how easily she recognised him from surveillance photographs: the dark hair, greying slightly at the temples; the narrow blue eyes, catching light from a window in the southern facade; a face at rest, giving nothing away, but with the faintest hint of mischief in the lines around his mouth. Not a noticeably handsome man, but striking and undeniably attractive. Cara had a habit of comparing people to animals. If Robert Vosse was a cow, plodding and decent, Matt Tomkins was a vulture, circling for carrion. If Cosmo de Paul was a weasel, sly and opportunistic, Lachlan Kite was not the bird of his codename, but rather a leopard, lean and prowling and solitary.

She sat at the end of a vacant pew, removed the sunglasses and immediately took out her mobile phone.

He’s here, she typed to Vosse, glancing up at Kite as she accidentally pressed ‘Send’ too early on WhatsApp. To her horror, she realised that Kite was looking directly at her. Cara returned to the message, her heart beating so fast that her hand began to shake as she held the phone. Dark grey suit, tailored. Slim. Six foot max. Appears to be alone.

The service was scheduled to begin in five minutes. Cara decided to return Kite’s gaze. If she could forge a connection with him, however briefly, it was more probable that he might talk to her in the aftermath of the funeral. That was the Holy Grail as far as Vosse was concerned: to get alongside BIRD and to cultivate a relationship with him.

She put the phone back in her coat pocket, composing herself. But when she turned and looked back towards the statue of St Matthew, Kite had disappeared.

Walking into the church, Kite was suddenly confronted by the sight of Martha talking with a crowd of university friends. He had not expected her to make the trip from New York. His heart thumped as she turned around – and he realised that he had been mistaken. It was just a trick of the light. The desire to see her, of which Kite had barely been conscious, had momentarily scrambled his senses.

Looking up at the vast, vaulted ceiling, the grandeur of the Oratory reminded him of the great chapel at Alford, religion on a scale Kite had never before experienced as a bewildered thirteen-year-old boy, arriving from the wilds of Scotland in an ill-fitting suit in the late summer of 1984. That first year at his new school had thrust him into a world of privilege and wealth with which at first Kite had struggled to come to terms. More than thirty-five years later, every second face in the Oratory was a pupil from those days or a friend of Xavier’s whom Kite recalled from the 1990s. The intervening years had not been kind to most of them. Kite was blessed with a photographic memory, but some were barely recognisable. The eyes remained constant, but the features, like his own, had been bullied by time. Everywhere he looked Kite saw slackened skin, thin, greying hair, bodies warped by age and fat. To his left, Leander Saltash, once a lean, aggressive opening batsman, now a bald, stooped television director with a BAFTA to his name; to his right, a man he took to be the diminutive, acne-ridden Henry Urlwin, now transformed into a six-foot beanpole with a chalky beard. Even Cosmo de Paul, that creature of the yoga retreat and the dyeing salon, looked washed out and slightly overweight, as if no vitamin supplement or exercise regime could reverse the inevitable decline of middle age.

‘Tell me. Did I fire six shots or only five?’

Kite felt two fingers pressed into his lower back, a hand clamped on his shoulder. It was a voice he hadn’t heard in years, a voice he had hoped, in all honesty, never to hear again. The voice of Christopher Towey.

‘Chris. How are you?’

Years ago, at Alford, Towey had obsessively watched the films of Clint Eastwood, quoting ad nauseam from the Harry Callaghan series to anyone who would listen. Every time Kite saw him, Towey made the same joke. He did so again in response to Kite’s reply.

‘Well, Lachlan, to tell you the truth, I’ve forgotten myself in all this excitement.’

Kite was in a bleak, uncooperative mood, thinking of Martha and Xavier. He didn’t recognise the quote and smiled as best he could, hoping they could skirt around Dirty Harry and Sudden Impact and talk like grown men.

‘It’s good to see you.’

‘You too, mate,’ Towey replied. ‘Christ, doesn’t everybody look so bloody old?’

‘Very.’

‘Age has withered us,’ he said. With dismay, Kite remembered that they had studied Antony and Cleopatra together for A level. Towey was still locked in the classroom, a man of forty-eight stalled for ever in his school days. ‘Custom has staled our infinite variety.’

‘It’s not that bad,’ Kite felt obliged to say, and suddenly wished that he had taken Isobel up on her offer to come with him. ‘People are probably happier now than they were twenty years ago. There’s a lot to be said for not being young. Fewer choices, less pressure. You look great, Chris. How’s married life?’

‘Divorced life nowadays.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘Don’t be. I’m bonking like a madman. Best-kept secret in London. If you’re a moderately well-financed middle-aged man with a British passport and some shower gel, the world’s your oyster. Poles, Brazilians, Uzbeks. Some days I can hardly walk.’

‘I’ll bear that in mind.’

‘So what have you been up to lately, eh? Last time I saw you, you were working in Mayfair. Oil or something.’

‘That’s right.’ Shortly after the attacks of 9/11, BOX 88 had been mothballed. Kite had taken a long sabbatical, then worked in the oil business for a small private company financing exploratory research in Africa.

‘Still doing that?’

‘Still doing that,’ Kite replied.

It was a lie, of course. Kite and Jean Lorenzo, his opposite number in the United States, had revived BOX 88 in 2016. In one of his final acts as president, Barack Obama had approved intelligence budgets totalling more than $90 billion, 7 per cent of which was diverted to ‘Overseas Contingency Operations’, a euphemism for BOX 88. Kite was now director of European operations working out of the Agency’s headquarters in Canary Wharf.

‘Tell you who thinks you’re a man of mystery. Remember Bill Begley? Always reckoned you were a spy.’

Kite had lived so long with the triplicate lives of the secret world, never settling down, always packing a bag and moving on, working one day in London, the next in Damascus, that people from time to time had suggested to his face that he was a spy. He had a well-honed response for such occasions which he used on Towey now.

‘I confess,’ he said, raising both hands in mock surrender. ‘Get the cuffs.’

Towey, never the brightest button in the Alford box, looked confused.

‘To be honest, I wish I had gone into that life,’ Kite added. ‘Lot more interesting than the work I’ve been doing the last ten years. But from what I understand, it doesn’t earn you any money. Foreign Office pays peanuts. Are you still in the City?’

Towey confirmed that he was indeed ‘making investments on behalf of private clients’ but was soon drawn into a separate conversation with a married couple whom Kite did not know. He grabbed the chance to leave. As he crossed the aisle, Xavier’s children, Olivier and Brigitte, walked in front of him. Kite had not seen them in years and was staggered by Olivier’s likeness to his father; it was as if the seventeen-year-old Xavier had walked past and failed to recognise him. Nearby, Kite spotted a senior French diplomat talking to a member of the Bonnard family; Kite knew that MI6 had recruited his number two in Brussels as part of the broad intelligence attack on EU officials during the Brexit negotiations. Two pews beyond them, Lena – Xavier’s long-suffering wife, herself a recovering heroin addict – looked at Kite as she sat down. He had written a letter of condolence to her within hours of Martha’s call, but could not tell from her reaction if she had read it. He raised a hand in greeting and Lena nodded back. She looked shattered.

A sudden silence settled on the congregation, punctured by organ music. Kite felt eyes on him. He looked up to find the woman he had seen walking alongside de Paul – still wearing oversized sunglasses and the black overcoat – staring in his direction. Had she recognised him? She sat down and began texting on a mobile phone.

‘Lachlan?’

Xavier’s younger sister, Jacqui, was gesturing at him from some distance away. The woman in the long overcoat removed her sunglasses and briefly looked at Kite a second time. He had never seen her face before – mid-twenties, alert and attractive – and wondered what had become of de Paul.

‘Communing with the tax collector?’ Jacqui asked.

She made her way towards him and they embraced. Kite felt the dampness of tears on her cheek as she kissed him.

‘What’s that?’

‘St Matthew,’ she said. ‘You’re standing underneath his statue. He was a tax collector. And here they are, the Catholic Church selling candles at fifty pence a pop.’

Jacqui indicated a box of candles nearby. She was uncharacteristically wired and jumpy. Kite assumed she was running on Valium and beta blockers.

‘I’m so sorry about Xav,’ he said, aware that there was nothing he could do or say to make the situation any better. ‘Did you get my letter?’

‘I got it,’ she replied. ‘You were very kind to write. Nobody knew Xavier like you did, Lachlan.’

The remark served only to stir up those same feelings of guilt which had dogged Kite since Martha’s phone call. His friend’s suicide had become a set of nails drawing down the blackboard of his conscience; he wished that he could be free of remorse, but could not shake the idea that what had happened in 1989 had shaped the entire corrupted course of Xavier’s life.

‘A better friend would have protected him,’ he said.

‘Nobody can save anybody,’ she replied. ‘Xav was the only person who could protect Xav.’

‘Maybe so.’

The service was due to start. Jacqui indicated that she should take her seat and they said farewell. Kite moved towards the centre of the church as Jacqui joined her family in the front row. A few seats away from his own sat Richard Duff-Surtees, an old Alfordian of towering arrogance and sadism who had called Kite a ‘pleb’ and spat on him in his first week at the school. Eighteen months later, seven inches taller and almost three stone heavier, the fifteen-year-old Kite had knocked him out cold with a clean right hook on the rugby field and been threatened with expulsion for his efforts. Duff-Surtees caught his eye during ‘Abide with Me’ and looked quickly away. It was the only pleasing moment in an otherwise heartbreaking hour of tears and remembrance. The family had asked for a High Mass and much of the service, to Kite’s frustration, was conducted in Latin. An agnostic from a young age, he loathed the smoke and mirrors voodoo of Catholicism, felt that Xavier would have insisted on something much lighter and more celebratory. Why was it that the upper classes, when confronted by emotional turbulence of any kind, retreated behind ceremony and the stiff upper lip? Kite was all for strength of character, but he had no doubt that Rosamund Bonnard and her waxwork friends would have grieved more openly for a Jack Russell or Labrador than for the death of their own child.

Singing the final hymn – the inevitable ‘Jerusalem’ – he looked around the church and decided to skip the wake. Better to stick twenty pounds in the collection box and slip away rather than risk another Eastwood quote from Chris Towey or, worse, a face-off with Cosmo de Paul. To that end, Kite waited in his seat until the church was almost empty, then walked out through a door in the south-eastern corner, wondering where he could grab lunch in South Kensington before setting off for the gallery.

Matt Tomkins told Vosse that Cara had panicked. As the service drew to a close, Kite had remained in his seat. Obliged to stand up to allow the mourners in her row the opportunity to leave, Cara had bottled it and gone with them, fearing that Kite would turn and notice that she was hanging around. Finding herself caught in a tide of Sloane Rangers shunting out of the Oratory, Jannaway had consequently lost sight of the target and been buttonholed by Cosmo de Paul on the steps of the Oratory.

‘So where is she now?’ Vosse asked.

‘Still talking to the man she was with before. Said his name was Cosmo de Paul. Pinstripe suit. It’s obvious he’s chatting her up, sir. I told you she was too attractive for surveillance work.’

‘Don’t talk crap,’ said Vosse, who was sitting in the Acton safe flat. He had high hopes for Cara but was worried that Kite was going to slip away yet again. Three times they had followed BIRD in central London. Three times he had vanished without trace.

‘It’s not crap, sir. I just call it as I see it.’

Tomkins had been sitting at the patisserie watching the traffic go by when Cara texted, telling him to get to the Oratory as fast as possible to help in the search for Kite. He had requested the bill – an eye-watering £18.75 for two cappuccinos and a slice of chocolate cake – and strolled across Brompton Road as the mourners continued to pour out of the church. He knew from Cara’s texts that Kite was wearing a tailored grey suit and black wool tie, but so were at least fifty of the other middle-aged men standing in clumps outside the church.

‘Head to HTB,’ Vosse told him on the phone.

‘What’s that?’ said Tomkins. He knew the answer to his own question the instant that he asked it; for the past hour he had been staring across the street at two signs next door to the Oratory bearing the letters ‘HTB’. But it was too late.

‘Holy Trinity Brompton,’ Vosse replied impatiently. ‘Pay attention. Protestant church round the back of the Oratory. Brainwashed evangelical Christians claiming to be possessed by the Holy Spirit. Posters advertising the Alpha Course and a better life with Bear Grylls and Jesus. You can’t miss it.’

Vosse had obviously done his homework, walking the ground the night before. Tomkins looked for a side door into the Oratory but couldn’t spot one. There was no sign of Kite. Black cabs were pulling up outside the church all the time. BIRD could easily have ducked into one and driven off while Cara was looking the other way.

‘Hello?’

She was on the phone again.

‘Yes?’ Tomkins replied.

‘Any luck?’

He looked over and saw Cara standing beside de Paul. She might as well have been holding a placard above her head emblazoned with the words: Have YOU seen Lachlan Kite? Vosse would have a field day when he found out.

‘Not yet, no,’ Tomkins replied. ‘I’m not really dressed for a funeral. If I come any closer, I’ll stick out as much as you do.’

‘Fuck’s sake,’ said Cara, looking up at the sky in dismay. ‘Just walk past or sit in a fucking bus stop. There are more people in Knightsbridge who look like you than there are people who look like me. Wait—’

Tomkins could tell by the note-change in her voice that she’d spotted Kite.

‘My days,’ she said. ‘I’ve got eyes on BIRD. He’s over by the wall.’

‘Another smoke?’ said the American, offering Kite a cigarette as the forecourt in front of the church slowly began to empty. The congregation was heading for a residential square to the west of the Oratory where drinks and snacks had been laid on in a hall reserved for mourners. Kite had stopped to check a message on his phone and liked the idea of a quick cigarette before lunch.

‘Would love one,’ he replied, wondering if the American had been targeted against him. ‘I never got your name.’

‘John,’ he said. ‘And you?’

‘Lachlan.’

Alcoholics Anonymous was decent cover for a phoney relationship with Xavier: most people wouldn’t pry into a stranger’s struggles with addiction, nor would anyone at the funeral know very much about Xavier’s experiences in the programme. Kite decided to probe a little deeper.

‘What did you make of Xav?’ he asked. ‘When he was down, could you bring him out of it? Did you ever have any success talking to him about his depression?’

It was a trick question. Xavier had been wild and unpredictable, but had consistently hidden his gloom from even his closest friends. Kite had never known him to complain, to cry on a shoulder, to lament the path his life had taken nor to despair over his addictions. He was, in his own particular way, every bit as stoic and uncomplaining as his mother. Outward displays of failure or self-pity were not in the gene pool.

‘Funny,’ John replied without hesitation. ‘I never knew him to be like that. Even in meetings he was always upbeat, always trying to find a way to make people laugh, to think more deeply when it came to their own situations.’ John appeared to have passed the test. ‘A lot of us were pretty down a lot of the time, present company included. Xav didn’t go in for that stuff. That’s why I can’t believe he did what they say he did. Had to be an accident, sex game or something.’

Xavier had been found in the bathroom of a Paris Airbnb, hanged by the neck. Unless somebody had staged the killing, it was suicide, pure and simple.

‘Maybe you’re right,’ Kite replied.

‘I’m sorry for your loss, man.’ John put his hand on Kite’s shoulder, his long, thick beard and the bright sunlight on his back momentarily giving him the look of an Old Testament prophet.

‘Yours too,’ Kite replied. ‘The world was a better place for having Xavier in it. We’re going to miss him.’

‘Lachlan?’

Kite turned. A striking man of Middle Eastern appearance had approached him from the western edge of the enclosure. He was wearing a dark grey lounge suit with a black tie and a crisp white shirt. A navy blue handkerchief protruded from the breast pocket of his jacket. Kite did not recognise him.

‘Yes?’

‘Excuse me.’ The man acknowledged the American, tipping his head apologetically. An expensive-looking watch caught the sun on his left wrist. ‘I don’t think you will remember me. I was at Alford, several years after you. My name is Jahan Fariba.’

Kite immediately recognised the name. Xavier had spoken about Fariba on one of the last occasions they had met. He was a businessman, British-born, his parents having fled Iran shortly after the revolution. Xavier had done business with him in a context Kite could not recall. He remembered that his friend had spoken fondly of him, on both a professional as well as personal basis.

‘Jahan. Yes. Xav talked about you. How did you recognise me?’

‘I’ll leave you guys to talk,’ John interjected, shaking Kite’s hand and moving off. Kite thanked him for the cigarettes. Fariba tipped his head respectfully at the American’s departure.

‘Jacqui told me who you were,’ he said, nodding in the direction of the church. ‘She pointed you out. I wanted to introduce myself.’

‘I’m glad you did.’

Fariba was in his late thirties. Fit and tanned, he resembled a recently retired professional athlete who still worked out twice a day, eschewed alcohol and went to bed at sunset six nights a week. It was late February and rare to see someone looking so vibrantly healthy.

‘Xav spoke of you, too. He was always going on about his old friend Lachlan.’

‘He was?’

Kite never liked hearing that. Xavier had known too much about his life in the secret world. The wrong word to the wrong person was an existential threat to his cover. He preferred to be anonymous: at worst the enigma at the back of the room; at best unnoticed and forgotten.

‘Yes. He was a great admirer of yours. I always wanted to meet you. I thought this would be a good opportunity. Are you going to the drinks now?’

Fariba’s accent was located somewhere between Tehran and Harvard Business School: an Americanised English characteristic of the international jet-set. He gestured towards the square.

‘Sadly not,’ Kite replied, indicating that he was short of time.

‘Me neither. I don’t feel like it. I didn’t know many of Xavier’s friends. What’s happened is awful. Just a terrible day.’

‘It really is.’ Beneath the slick, executive exterior Kite glimpsed a softness in Fariba. ‘When did you last see him?’

‘This is what I wanted to talk to you about.’ Fariba lowered his voice to a confessional whisper which was almost drowned out by the noise of a passing bus. ‘I was with him less than two weeks ago, in Paris, the night before he died.’

Cara had worked up a possible pitch with Vosse. The drug addict friend from South Africa was too risky to play on Kite, who had known Xavier well and would quickly smell a rat. Instead she would play the art card. They knew from the MI6 whistle-blower that Kite had an interest in collecting paintings. He’d been seen at the Frieze fair back in October and had exchanged emails with several dealers. Cara had briefly studied Fine Art at university before switching to Politics and knew how to talk shit about painters and paintings. She could say she’d had a temp job at one of the galleries exhibiting at Frieze and had recognised Kite as a prospective buyer. That would be enough to start a conversation, perhaps even to lead to an exchange of numbers. Vosse had joked that he wanted Cara to get to know Kite so well that he would ask her to be the au pair for Isobel’s baby when it was born in the summer. Cara preferred to think that Kite would try to recruit her into BOX 88.

But when to approach him? Outside the Oratory, Kite had been trapped in two conversations: the first with the tall, bearded man who had offered him cigarettes; the second with a good-looking businessman, possibly of Arab descent, wearing thousand-dollar shoes and an expensive suit. After what had happened before the service, Cara reckoned she could bump Kite and take her chances with an open pitch.

‘What’s going on?’

Matt Tomkins was on the phone again, calling for no good reason other than to make her afternoon more difficult than it already was.

‘What’s going on is that you’re making me answer the phone when what I want to be doing is getting on with my job. What do you want?’

‘Just to let you know, Eve and Villanelle are outside Smallbone in the Astra.’

‘Eve’ was the codename for Tessa Swinburn, ‘Villanelle’ was Kieran Dean. Vosse had a penchant for naming team members after characters in television shows. Cara looked across the busy street. There was a branch of Smallbone of Devizes on the corner of Thurloe Place. She couldn’t see the Vauxhall Astra but assumed it was parked nearby.

‘Great. Can I go now?’ she said.