Полная версия

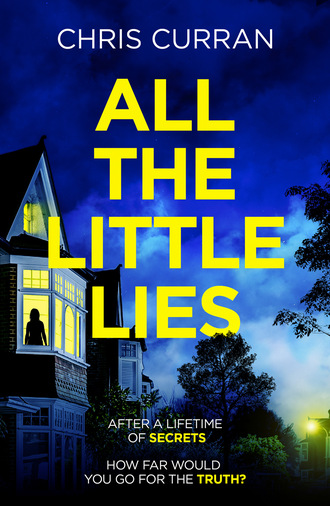

All the Little Lies

Thank goodness for Maggie, thundering up the stairs even faster than usual. Stella put down her brush as her bedroom door burst open. ‘Where’s the fire?’

Maggie ignored her and threw herself on Stella’s bed. ‘Got anything decent to wear?’ She laughed and before Stella could speak, ‘Don’t answer that. Come to my room and try something on.’

There was no point in arguing and anyway it would be too dark to carry on soon. ‘Where are we going?’ Since she’d come to live with Maggie – been taken under her wing was how Maggie described it – she’d had the kind of social life she’d only ever dreamed of.

Maggie’s room was even untidier than Stella’s and she flung open her bursting wardrobe and tossed a great pile of dresses onto the unmade bed. As Stella picked through them Maggie pulled off her own jeans and shirt and stood in her black bra and lacy knickers, one hand on her hip, studying Stella and shaking her head as she held dress after dress up to her shoulders. Stella knew her own figure wasn’t bad. She and Maggie were pretty much the same size but she would never have Maggie’s confidence. Came from always having had money she guessed. The best schools and all that. This house actually belonged to Maggie. Before coming to art school Stella had never known anyone who owned their own house and it was almost unbelievable that someone in her early twenties could do so.

‘I can’t choose until I know where we’re going, Margot.’ She grinned as she said it, knowing Maggie hated the name her parents had given her. Hated them too for that matter. She said her dad had only gifted her this house so he wouldn’t feel bad about moving to the States with his new young wife. At least that was more than she’d had from her mother who, according to Maggie, had deserted them when she was a toddler. The fact that neither Maggie nor Stella – now her nana no longer recognized her – had any real family had helped their friendship develop.

Maggie threw a shoe in Stella’s direction and plonked down among the pile of clothes, lighting a cigarette and talking through puffs. ‘My man has invited us to a gallery opening. So pick something tres glam.’

The gallery was beautiful. All pale walls with black leather sofas. Waiters circulated carrying trays of champagne. Stella had never had it and wasn’t sure she liked it, but Maggie swallowed hers in one gulp and grabbed another. Then Stella felt her stiffen beside her.

‘Damn it, the old bitch is here.’

Following her gaze across the room Stella saw a tall, blonde woman in a slender black dress. Her hair gleamed under the lights, and just looking at her made Stella feel like a scruffy midget. This must be the wife of Maggie’s current man, Ben. Maggie liked older men and was never bothered if they were married.

It had to be Ben who approached them. He took both Maggie’s hands in his and kissed her cheek and from the way Maggie stroked his jacket and gazed up at him Stella could tell he was more than one of her flings – a lot more.

He was probably at least forty, but very handsome in a dark Irish kind of way. ‘It’s Maggie, isn’t it?’ he said, his eyes twinkling.

With a quick glance around, Maggie punched his arm. ‘You never told me she would be here,’ she hissed.

‘Couldn’t be helped, I’m afraid, but I doubt you’ll be lonely.’ He turned to Stella. ‘And that goes for both of you.’ He took her hand, and she felt herself flush, wishing she’d had time to wipe it on her dress because it felt sticky. He looked from her to Maggie. A flash of white teeth. ‘Are you related?’

Maggie moved closer to him, touching his arm. Her voice turning gruff. ‘Stella is my flatmate.’

‘Ah, just alike in beauty then. So are you an artist too, Stella?’

‘An art student, yes.’

‘That’s wonderful. Did Maggie tell you we’re planning a small exhibition of young talented folk like yourselves? We’ve already snapped up a couple of Maggie’s collages.’

Before she could answer he beckoned to another man who had been talking to an elderly couple nearby.

‘You must meet my partner, David Ballantyne. He knows more about art than anyone in London.’

As the other man came over Ben said, ‘David, meet two of the young talents for our new show.’ Then he gave Maggie’s bottom a pat and headed away.

David was a bit younger than Ben. Mid-thirties Stella guessed. He was nice-looking where Ben was handsome, with fair hair and glasses, but still looked good in his dinner jacket and black specs. His smile was friendly, but he seemed embarrassed to be stranded with them, especially with Maggie rather obviously scowling after Ben’s retreating back.

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t catch your names,’ he said, and Stella thought she detected a hint of a Scottish burr.

Maggie gave him her brilliant smile and held out her hand. ‘Maggie de Santis.’ She always pronounced her surname with an almost comical Italian accent. Despite hating her first name, and the parents who gave it to her, Maggie was very proud of the fact that her ancestors had been Italian aristocracy. She tossed back her shining chestnut hair. ‘You and Ben chose two of my collages for the show.’

David’s eyes crinkled as he turned to Stella with a laugh. ‘Ah, that explains where I’ve seen you before. It’s a very amusing picture, although not a good likeness if I may say so.’

The collage he must be talking about had lots of photos of Maggie’s friends in the most bizarre poses and situations. Stella’s face was right in the middle; she was wearing a bathroom plunger as a hat, decorated with a huge feathery-topped carrot. Her laugh came out too loud. She had no idea Maggie had got the picture into an exhibition.

Maggie smacked David’s hand. ‘Naughty boy. That was supposed to be a surprise.’

Stella could never believe how confident Maggie was with men who were so much older and more sophisticated. But then looking at the way David’s face had flushed perhaps he wasn’t so sophisticated after all.

His eyes were still on Stella. ‘I don’t remember seeing any of your work.’

‘You haven’t.’ It sounded rude and she was very aware of her Geordie accent but he didn’t seem bothered.

‘Well why don’t you bring some stuff in tomorrow for me to see?’

Someone waved from across the room, and he smiled and told them to enjoy the evening and was gone. Stella’s heart was beating so fast she thought she might collapse. And when Maggie grabbed her arm she leaned in to her for support.

‘Oh my god! Thank you so much.’

Maggie tapped her glass with her own. ‘That’s what friends are for. He’ll love your stuff. And I wouldn’t be surprised if he’s taken a fancy to you, too.’

Stella told her not to be silly, but watching him smiling and chatting as he moved around the room she did think he looked rather lovely.

Eve

The doorbell to the flat shrilled into the silence. They all ignored it. Eve didn’t take her eyes off David. Could he be her real father? Surely not. She knew how much he loved Jill. But no marriage was perfect and she guessed her parents’ must have come under strain when they realized they couldn’t have children of their own.

As if he knew what she was thinking David met her eyes and shook his head. His voice was suddenly old and weary. ‘We were wrong to keep all this from you, but there never seemed to be a right time.’

The doorbell pierced the air again, a long ring, but Jill spoke over it. ‘But we were all so happy, weren’t we? How could that be wrong?’

Eve’s phone began to buzz on the table – Alex. She had to answer.

‘I’m outside. Got your message.’ He must have come straight from the train.

‘I thought we could drive home together. The light’s not good at this time of night.’

She bit down on a spasm of annoyance. She was a better driver than Alex even with her bump. Why did he insist on treating her like an invalid?

‘Stay there,’ she said, ‘I’ll be down in a minute.’

Her father said, ‘Eve, my darling …’

She shook her head and held up her hand to keep him from going on. ‘It’s all right, just leave me to think about it.’ She shoved the article into her bag and turned to her mother. ‘But please try to find that letter for me.’

As she was buttoning her jacket, Jill said, ‘Why don’t I come round tomorrow morning and we can talk this through? You can ask me anything you want then.’

Eve nodded. ‘OK.’ She must have said it more coldly than she meant because Jill’s face crumpled.

‘Eve, you must believe we’ve always done our best by you,’ she said pulling at the curls on the nape of her neck.

It was a gesture so familiar that Eve felt a twist of pain deep inside. She said, ‘I know you have,’ and kissed her mother’s cheek. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow.’

Alex talked about work on the drive home, but she was hardly listening. He was twenty years older than her and taught art history at University College London. It was how they had met. They hadn’t got together until just before she graduated, and he never actually taught her. Her parents weren’t too happy at the time. He’d been married before and Eve knew they were hoping she would come back to live with them for a while after she graduated, but there was never any chance of that. Although she couldn’t have hoped for a better childhood, her teenage years had been difficult as she began to find their love stifling.

They’d grown to like Alex when they realized how happy he made her, especially when he agreed with Eve that they would move to Hastings after her mother’s heart attack.

As they pulled up outside the house he said, ‘What’s wrong?’

She wasn’t ready to talk about it in the car, so she shook her head and, despite the baby bulk, got out quickly and had let herself in by the time he’d retrieved his briefcase from the back seat and locked the car.

Standing in the kitchen she could hear him take off his coat and walk in behind her. When she turned, his kiss was so warm and familiar she felt bad for shutting him out.

‘Come on, Eve, tell me,’ he said.

She took the scrunched-up article from her bag, then pulled him into the living room to make him sit on the sofa beside her. ‘I found out today that my parents have been lying to me all my life.’

He took the article and glanced at her, expecting her to explain, but she tapped the paper and he fumbled in his pocket for his reading glasses. ‘What is it?’

‘Just read it, please, Alex. I’ll go and dish the dinner up.’

She’d made a casserole in the slow cooker, so there was nothing much to do except to lay the table and put on some microwave rice. She expected Alex to come and talk to her when he’d finished reading, but he didn’t, so she ladled out the food and called him. When she handed him his plate he didn’t look at her.

‘Alex? You realize who she is, don’t you? And my parents lied to me about knowing her.’

He grabbed her hand and squeezed it. ‘I’m sorry, sweetheart, that must have come as a real shock. I can understand you being upset, but I suppose they thought it was for the best.’

She knew her voice sounded bitter. ‘Best for me or for them?’

‘Well I’m sure it would have upset you to know your mother was dead. And when would be the right time to come out with something like that? Did they tell you what she died of?’

‘Just that it was an accident.’ She shuddered. ‘She died in a fire – how awful.’

‘Oh, no. Well, that would have been a difficult thing to tell a child.’

‘And there’s the suggestion that it was mysterious. Whatever that means.’

They were both silent, thinking about it, until Eve felt a kick from the baby that was so hard it made her cry out.

Alex said, ‘All right?’

‘Yeah. Just a kick.’

‘All the same, you look exhausted. Maybe you should get an early night.’

She wanted to tell him to leave the worrying to her, but she knew how much this baby meant to him. It meant a lot to her too, of course. She was thirty-one and they’d tried for three years before she got pregnant. Although Alex looked wonderful for over fifty – his hair was still thick and there were no signs of grey – he’d been anxious that he might be too old for babies soon. And of course he’d already lost two children. His first wife had taken his son and daughter to Australia after the divorce and had apparently told them all sorts of lies about Alex, so they refused to see him. They were teenagers now, but he didn’t even know how to contact them.

She touched the article. ‘Have you noticed the date of the Houghton exhibition?’

‘Yes, the year before you were born.’

‘I looked it up. It was just over nine months before.’

Alex studied the report again, then put down his glasses. ‘You’re not thinking …?’

‘It makes sense. Young artist trying to make it and an influential older man.’

Alex shook his head. ‘No, I can’t believe that of David.’

‘He knew Stella at the time and if they did have an affair he could have been lying to Mum all these years as well as to me. Or maybe she decided to forgive and forget. Just glad to get a baby.’

‘Eve, this is ridiculous. It’s your parents we’re talking about.’

‘I wonder what he’ll say if I ask for a DNA test?’

‘You wouldn’t do that, would you?’

She suddenly felt enormously weary. ‘I don’t know.’ Alex was right that she needed to rest and she wanted to be alert when her mother came round tomorrow. She collected their dishes, tipped the remains in the bin and put the plates into the sink. ‘I think I will go up now.’ She kissed his hair, but stopped at the door. ‘You know, after what I’ve learned about my parents today I don’t feel I know them at all.’

She fell into a fitful sleep as soon as she was in bed. At one point, half-awake and not sure if she was dreaming, she thought she heard Alex talking to someone on the phone.

CHAPTER THREE

Stella

Stella had delivered two paintings to the Houghton Gallery. Holding them at arm’s length, as if they were grubby or possibly dangerous, the glamorous receptionist had put them into a cupboard behind her desk and said Mr Ballantyne would call when he’d had a chance to see them. It was clear she didn’t expect the news to be positive.

That was two days ago and, although Maggie told her she was stupid to be downcast, she kept expecting a request to remove her rubbish from the premises.

She had spent the morning at the Tate Gallery. She loved the place and at the moment they had a small exhibition of a group of artists who worked in the East End of London during the 1930s. One of them, George Grafton, was her favourite. Many of his paintings had been destroyed in the 1941 air raid in which he died: but some of his drawings had survived and she found copying them oddly soothing. She’d even started doing one or two of her own in his style. They were quite different from her usual stuff, but that was part of the pleasure. Made it more like playing than work.

It was a lovely afternoon and when she walked down the steps from the gallery there was the first hint of spring in the air. The Thames across the road glittered; each ripple sparkling as it caught the sunlight.

When she opened the front door, calling to Maggie as she did so, Ben waltzed out of the living room. Maggie was behind him looking furious, and Stella headed towards the stairs. Best to make herself scarce.

But Ben was looking at her with a broad smile. ‘Ah, just the girl I want to see.’

She stopped and glanced at Maggie, but she muttered something and went into the kitchen closing the door behind her.

Ben said, ‘David hasn’t stopped raving about your work for two days. Wants to make it the centre of the exhibition. If he has anything to do with it you’re going to be a star.’

Stella stopped halfway up the stairs. After what seemed an age she managed to say, ‘Thank you. That’s wonderful.’

Ben was rubbing his hands together. ‘Now, I’ve got the car outside and Maggie tells me you have more work complete. So what do you say we load the boot and take it to the gallery now?’ He bounded up past her, holding out his hand to take her drawing folder from her.

She hadn’t made her bed this morning and there were clothes scattered on the floor and dirty cups on the bedside table and the window ledge.

With her folder under his arm, Ben headed straight for the picture of her nan on the easel, touching it with a fingertip to check it was dry. ‘Right, we’ll take this one and …’ He turned to the canvases propped up by the wall. ‘This and this and, yes, this too.’

In less than ten minutes they had carried them out to his car.

As she left the house she called, ‘Goodbye,’ to Maggie. There was no reply.

Eve

As soon as Alex left in the morning Eve went onto the Internet looking for more information about Stella. There were several reports on the Baltic exhibition, talking of her talent and the tragedy of her early death. Only one gave any details about that and as Eve read she felt something cold clench deep inside.

Stella’s death was tragic. She had recently moved to Italy and was painting in a garden studio when it burned down. There were some suggestions that she was depressed at the time, but the Italian authorities eventually declared her death accidental.

Depressed at the time. Eve looked away from the screen and turned the phrase over in her mind. Where had those suggestions come from? The article was from The Guardian, so she found the contact details for the columnist and wrote a message.

I’m doing some research into the life and work of Stella Carr and wondered if you could tell me where the suggestions that she might have been depressed before her death came from.

She thought about it for a moment and added:

I’m working with Dr Alex Peyton and with David Ballantyne.

It was true, up to a point, and she hoped her own name, Eve Ballantyne, might help to give her enquiry more substance.

She couldn’t stop that phrase depressed at the time from echoing in her head. Was it code for suicidal? Eve knew about depression. Her first year teaching art in a tough London comprehensive had been difficult. She had been trying to make a go of her own painting; working late into the night after she’d completed everything for school. Alex had been supportive, but eventually she had a breakdown. It was a nightmare that went on for months and, just as she was beginning to come back to herself, her mother’s heart attack sent her back into turmoil. But that turned out for the best. They moved down to Hastings, she took a job in a local school and loved it. Nowadays she hardly painted.

What if she’d inherited a tendency to depression? She shook her head. Nothing good could come of thinking like that.

It didn’t help that when her mum arrived at the house later that morning her first words were, ‘Eve, you look exhausted.’

She forced herself not to say that it might be because of the shock she’d had yesterday. During her teenage years she had fought with Jill all the time and she still felt guilty about that.

As usual Jill headed for the kitchen, opening the lid of the cake tin she was carrying. ‘I made a sponge.’

Eve had expected this and, although she was desperate to get down to talking about Stella, she had already percolated the coffee and put mugs and plates on the table. Her jaw tensed as she watched her mother cut the cake saying, ‘What do you think? I thought it looked a bit dry.’ Just like any normal day.

Eve nibbled at a few crumbs. ‘It’s fine. Lovely, as always. Now please, Mum, tell me everything.’

After what seemed an age Jill put her palms together and said, ‘We’re sorry for not being honest with you. We spent all last evening talking about it and your father seems to think the friend who let us know about Stella’s death was the girl with her in the painting from the article – Maggie. He vaguely remembers her from the time of the Houghton exhibition and has an idea that Stella was sharing a house with her.’

This was something. ‘What was her surname?’

‘He can’t remember. Only that she had some collages in the show. Apparently they weren’t very good. Ben chose them and he wasn’t the greatest judge of art.’

‘Gallery owner was a strange choice of career for him then.’

‘Dad says he liked the glamour of it. It actually belonged to his wife, Pamela. She had the money and was a bit of a socialite, enjoyed hosting openings and so on. Not something I was interested in. I hardly ever went there.’

Eve told herself to be patient. It wasn’t easy. ‘So you never met Stella?’

Her mother fitted the lid of the cake tin back on, pressing it carefully into place. Still smoothing her hands over it, she spoke without looking at Eve. ‘Actually she stayed with us for a while before you were born.’

‘What?’ Eve plonked her mug down so hard the coffee splashed on her hand. She rubbed it off with the sleeve of her jumper, struggling to get the words out. ‘Stella lived with you down here?’ She was, what was the word? Damn pregnancy for making her head so woolly. Astounded, that was it, she was astounded. She’d assumed her mother had only met Stella when they picked up the baby (it was impossible to think of that child as herself).

‘She didn’t have anywhere else to go, you see. No family and I think she had to move out of the place where she was living.’

‘With Maggie?’

‘I suppose so. Although …’

‘So it wasn’t just Dad? You knew my birth mother too and you never told me.’ It was little more than a gasp.

Jill moved back – away from her – and turned her mug round and round on the table looking at it with intense concentration. Her voice wobbled. ‘We never set out to keep anything from you.’

‘But you did. You knew her. You could have told me what she was like. You could have told me so many things. Even the fact that my mother was an artist might have made me try a bit harder with my own painting.’ A chill shivered through her. ‘Was she so horrible you thought it better I didn’t know?’

Jill grabbed her hand. ‘Of course she wasn’t. Like we always said, she was a young girl in an impossible situation. And giving you to us was her way of doing the best she could for you.’

Eve looked into the hazel eyes she knew so well. The eyes that had comforted her when she was a little girl crying over a scraped knee or a bust-up with her friends. Eve’s own eyes were a similar colour and she’d always been happy about that. It seemed to connect them.

‘Please, Mum, tell me everything. I mean how did Dad even find out about her pregnancy if he hardly knew her?’

Her mother shook her head and took in a shuddering breath. ‘I know what you’re thinking, but there was nothing between them. He would never have done that to me. He’s always been the kind of person people can talk to and she confided in him. She was alone and virtually penniless. She came to live here because she had nowhere else to go.’

This was unbelievable. ‘You must have got to know her then.’

‘Not really. She was very quiet and she wasn’t here long.’

‘And how did you first find out about her death?’

Her mother shook her head. ‘I’m not sure. Through people in the art world I suppose. The note came later and even that was just a few lines. The truth is, and I’m sorry if this makes us sound callous, we knew Stella for such a short time and we began, very early on, to think of you as our own. We loved you so much right from the start that we didn’t want to be reminded of how you came into our lives. But we’ve always been grateful to her.’