Полная версия

When Did You See Her Last?

When Did You See Her Last? First published in Great Britain 2013 by Egmont UK Limited The Yellow Building 1 Nicholas Road London W11 4AN www.egmont.co.uk

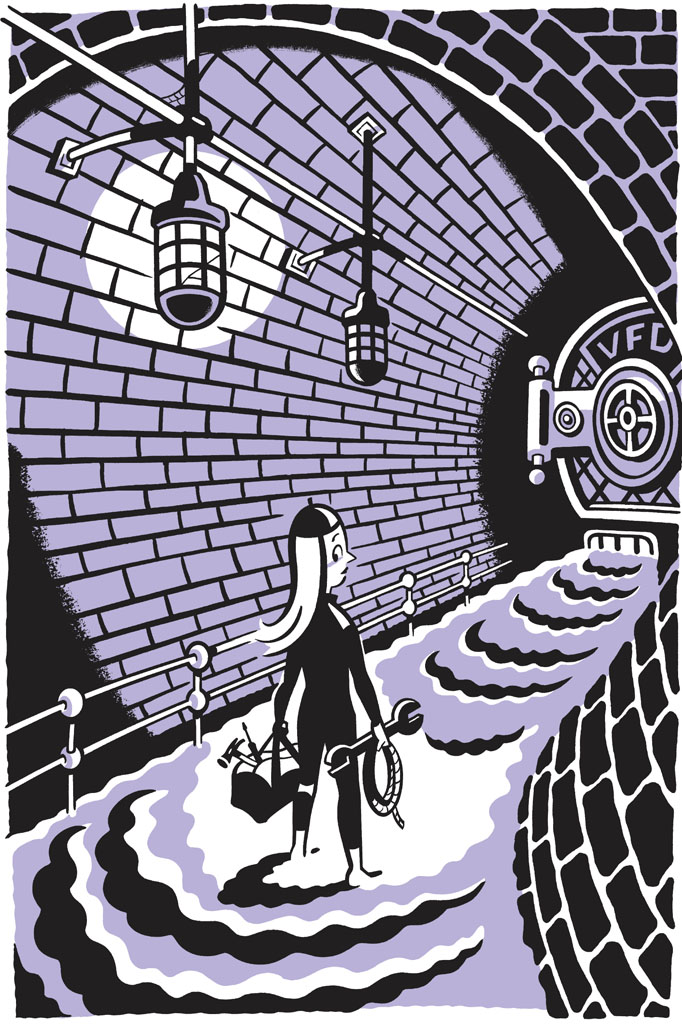

Text copyright © 2013 Lemony Snicket

Art copyright © 2013 Seth

ALL THE WRONG QUESTIONS: When Did You See Her Last? by Lemony Snicket reprinted by arrangement with Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency.

Illustrations published by arrangement with Little, Brown, and Company, New York, New York, USA. All rights reserved.

The moral rights of the author and artist have been asserted

First e-book edition 2013

978 1 4052 5622 3

eISBN 978 1 7803 1231 6

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties.

ALL THE WRONG QUESTIONS

“Who Could That Be at This Hour?”

“When Did You See Her Last?”

CONTENTS

Cover

Title page

Copyright

Front series promotional page

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

About the Author

TO: Pocket

FROM: LS

FILE UNDER: Stain’d-by-the-Sea, accounts of; kidnapping, investigations of; Hangfire; skip tracing; laudanum; doppelgängers; et cetera

2/4

cc: VFDhq

There was a town, and there was a statue, and there was a person who had been kidnapped. While I was in the town, I was hired to rescue this person, and I thought the statue was gone forever. I was almost thirteen and I was wrong. I was wrong about all of it. I should have asked the question “How could someone who was missing be in two places at once?” Instead, I asked the wrong question—four wrong questions, more or less. This is the account of the second.

It was cold and it was morning and I needed a haircut. I didn’t like it. When you need a haircut, it looks like you have no one to take care of you. In my case it was true. There was no one taking care of me at the Lost Arms, the hotel in which I found myself living. My room was called the Far East Suite, although it was not a suite, and I shared it with a woman who was called S. Theodora Markson, although I did not know what the S stood for. It was not a nice room, and I tried not to spend too much time in it, except when I was sleeping, trying to sleep, pretending to sleep, or eating a meal. Theodora cooked most of our meals herself, although “cooking” is too fancy a word for what she did. What she did was purchase groceries from a half-empty store a few blocks away and then warm them up on a small, heated plate that plugged into the wall. That morning breakfast was a fried egg, which Theodora had served to me on a towel from the bathroom. She kept forgetting to buy plates, although she occasionally remembered to blame me for letting her forget. Most of the egg stuck to the towel, so I didn’t eat much of it, but I had managed to find an apple that wasn’t too bruised and now I sat in the lobby of the Lost Arms with its sticky core in my hand. There wasn’t much else in the lobby. There was a man named Prosper Lost, who ran the place with a smile that made me step back as if it were something crawling out of a drawer, and there was a phone in a small booth in the corner that was nearly always in use, and there was a plaster statue of a woman without clothes or arms. She needed a sweater, a long one without sleeves. I liked to sit beneath her on a dirty sofa and think. If you want to know the truth, I was thinking about Ellington Feint, a girl with strange, curved eyebrows like question marks, and green eyes, and a smile that might have meant anything. I had not seen that smile for some time. Ellington Feint had run off, clutching a statue in the shape of the Bombinating Beast. The beast was a very terrible creature in very old myths, whom sailors and citizens were worried about encountering. All I was worried about was encountering Ellington. I did not know where she was or when I might see her again. The phone rang right on schedule.

“Hello?” I said.

There was a careful pause before she said “Good morning.” “Good morning,” she said. “I’m conducting a voluntary survey. ‘A survey’ means you’ll be answering questions, and ‘voluntary’ means—”

“I know what voluntary means,” I interrupted, as planned. “It means I’ll be volunteering.”

“Exactly, sir,” she said. It was funny to hear my sister call me sir. “Is now a good time to answer some questions?”

“Yes, I have a few minutes,” I said.

“The first question is, how many people are currently in your household?”

I looked at Prosper Lost, who was across the room, standing at his desk and looking at his fingernails. Soon he would notice I was on the phone and find some reason to stand where he might eavesdrop better. “I live alone,” I said, “but only for the time being.”

“I know just what you mean.” I knew from my sister’s reply that she was also in a place without privacy. Lately it had not been safe to talk on the phone, and not only because of eavesdroppers. There was a man named Hangfire, a villain who had become the focus of my investigations. Hangfire had the unnerving ability to imitate anyone’s voice, which meant you could not always be sure whom you were talking to on the telephone. You also couldn’t be sure when Hangfire would turn up again, or what his scheme might be. It was entirely too many things to be unsure about.

“In fact,” my sister continued, “things in my own household have become so complicated that I am unsure I can get to the library anymore.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” I said, which was code for being sorry to hear that. Recently my sister and I had been communicating through the library system. Now she seemed to be telling me that it would no longer be possible.

“My second question is, do you prefer visiting a museum alone or with a companion?”

“With a companion,” I said quickly. “Nobody should go to a museum alone.”

“What if you could not find your usual companion,” she asked, “because he was very far away?”

I wasted a few seconds staring at the receiver in my hand, as if I could peer through the little holes and see all the way to the city, where my sister was, like me, working as an apprentice. “Then you should find another companion,” I said, “rather than visiting a museum by yourself.”

“What if there were no other suitable companions?” she asked, and then her voice changed, as if someone had walked into the room. “That’s my third question, sir.”

“Then you should not go to the museum at all,” I said, but then I, too, was interrupted, by the figure of S. Theodora Markson coming down the stairs. Her hair came first, a wild tangle as if several heads of hair were having a wrestling match, and the rest of her followed, frowning and tall. There are many mysteries I have never solved, and the hair of my chaperone is perhaps my most curious unsolved case.

“But sir—” my sister was saying, but I had to interrupt her again.

“Give Jacques my regards,” I said, which was a phrase which here meant two things. One was “I must get off the phone.” The other thing the phrase meant was exactly what it said.

“There you are, Snicket,” Theodora said to me. “I’ve been looking for you everywhere. It’s a missing-persons case.”

“It’s not a missing-persons case,” I said patiently. “I told you I was going to be in the lobby.”

“Be sensible,” Theodora told me. “You know I don’t listen to you very well in the morning, and so you should make the proper adjustments. If you’re going to be someplace in the morning, tell me in the afternoon. But where you are is neither here nor there. As of this morning, Snicket, we’re skip tracers.”

“Skip tracers?”

“‘Skip tracer’ is a term which here means ‘a person who finds missing persons and brings them back.’ Come on, Snicket, we’re in a great hurry.”

Theodora had an impressive vocabulary, which can be charming if it is used at a convenient time. But if you are in a great hurry and someone uses something like “skip tracer,” which you are unlikely to understand, then an impressive vocabulary is quite irritating. Another way of saying this is that it is vexing. Another way of saying this is that it is annoying. Another way of saying this is that it is bothersome. Another way of saying this is that it is exasperating. Another way of saying this is that it is troublesome. Another way of saying this is that it is chafing. Another way of saying this is that it is nettling. Another way of saying this is that it is ruffling. Another way of saying this is that it is infuriating or enraging or aggravating or embittering or envenoming, or that it gets one’s goat or raises one’s dander or makes one’s blood boil or gets one hot under the collar or blue in the face or mad as a wet hen or on the warpath or in a huff or up in arms or in high dudgeon, and as you can see, it also wastes time when there isn’t any time to waste. I followed Theodora out of the Lost Arms to where her dilapidated roadster was parked badly at the curb. She slid into the driver’s seat and put on the leather helmet she always wore when driving, which was the primary suspect in the mystery of why her hair always looked so odd.

We were in a town called Stain’d-by-the-Sea, which was no longer by the sea and was hardly a town anymore. The streets were quiet and many buildings were empty, but here and there I could see signs of life. We passed Hungry’s, a diner I had yet to try, and I saw through the window the shapes of several people having breakfast. We passed Partial Foods, where we purchased our groceries, and I saw a shopper or two walking among the half-empty shelves. Black Cat Coffee had a solitary figure at the counter, pressing one of the three automated buttons that gave customers coffee, bread, or access to the attic, which had served as a good hiding place. On this drive I also noticed something new in town—something pasted up on the sides of lampposts, and on the wood that barricaded the doors and windows of abandoned houses. Even the mailboxes had the posters on them, although from the hurrying roadster I could only read one word on them.

“This is a very crucial matter,” Theodora was saying. “We were given this important case because of our earlier success with the theft of the statue of the Bombinating Beast.”

“I would not call it success,” I said.

“I don’t care what you would call it,” Theodora said. “Try to be more like your predecessor, Snicket.”

I was tired of hearing about the apprentice before me. Theodora had liked him better, which made me think he was worse. “We were hired to return that statue to its rightful owners,” I reminded her, “but that turned out to be one of Hangfire’s tricks, and now both the item and the villain could be anywhere.”

“I think you’re just mooning over that girl Eleanor,” Theodora said. “Cupidity is not an attractive quality in an apprentice, Snicket.”

I was not sure what “cupidity” meant, but it began with the word “Cupid,” the winged god of love, and Theodora was using the tone of voice everyone uses to tease boys who have friends who are girls. I felt myself blushing and did not want to say her name, which wasn’t Eleanor. “She is in danger,” I said instead, “and I promised to help her.”

“You’re not concentrating on the right person,” Theodora said, and tossed a large envelope into my lap. The envelope had a black seal on it that had been broken. Inside was nothing but a piece of paper with a photograph of a girl several years older than I was. She had hair so blond it looked white and glasses that made her eyes look very small. The glasses were shiny, or maybe just reflecting the light of the camera’s flash. Her clothes looked brand-new, with brand-new black-and-white stripes like a zebra that had been recently polished. She was standing in what I guessed to be her bedroom, which also looked brand-new. I could see the edge of a shiny bed and a shiny dresser stacked with trophies that looked as if they had been awarded yesterday. Most trophies I’d seen had figures of athletes at the top of them. These had shapes that were bright and strange. They reminded me of illustrations in a science book, explaining the very small things that supposedly make up the world. The only things in the photograph that did not look brand-new were the hat she was wearing, which was round and the color of a raspberry, and the frown on her face. She looked displeased at having her photograph taken, and also like she used her displeased expression quite frequently. Printed underneath the frowning girl was her name, MISS CLEO KNIGHT, and at the top of the poster was printed another word, in much bigger type. It was the same word I had read on the copies of the same flyer all over town.

MISSING.

The word applied to the girl, but it could have applied to anything in town. Ellington Feint had vanished. Theodora’s roadster sped down whole blocks that had been emptied of businesses and people. I realized we were heading toward the town’s tallest building, a tower shaped like an enormous pen. Once this town had been known for producing the world’s darkest ink, from frightened octopi shivering in deep wells that were once underwater. But the sea had been drained away, leaving behind an eerie, lawless expanse of seaweed that somehow still lived even when the water had disappeared. Nowadays there were few octopi left, and eventually there would be nothing at all but the shimmering seaweed of the Clusterous Forest. Soon everything will go missing, Snicket, I thought to myself. Your chaperone is right. You are in a great hurry. If you do not hurry to find what has gone missing, there will be nothing left.

The pen-shaped tower had a surprisingly small door printed with letters that were far too large. The letters said INK INC., and the doorbell was in the shape of a small, dark ink stain. It was the name of the largest business in Stain’d-by-the-Sea. Theodora stuck out a gloved finger and rang the doorbell six times in a row. There was not a doorbell in the world that Theodora did not ring six times when she encountered it.

“Why do you do that?”

My chaperone drew herself up to her full height and took off her helmet so her hair could make her even taller. “S. Theodora Markson does not need to explain anything to anybody,” she said.

“What does the S stand for?” I asked.

“Silence,” she hissed, and the door opened to reveal two identical faces and a familiar scent. The faces belonged to two worried-looking women in black clothes almost completely covered in enormous white aprons, but I could not quite place the smell. It was sweet but wrong, like an evil bunch of flowers.

“Are you S. Theodora Markson?” one of the women said.

“No,” Theodora said, “I am.”

“We meant you,” said the other woman.

“Oh,” Theodora said. “In that case, yes. And this is my apprentice. You don’t need to know his name.”

I told them anyway.

“I’m Zada and this is Zora,” said one of the women. “We’re the Knight family servants. Don’t worry about telling us apart. Miss Knight is the only one who can. You’ll find her, won’t you, Ms Markson?”

“Please call me Theodora.”

“We’ve known Miss Knight since she was a baby. We’re the ones who took her home from the hospital when she was born. You’ll find her, won’t you, Theodora?”

“Unless you would prefer to call me Ms Markson. It really doesn’t matter to me one way or the other.”

“But you’ll find her?”

“I promise to try my best,” Theodora replied, but Zada looked at Zora—or perhaps Zora looked at Zada—and they both frowned. Nobody wants to hear that you will try your best. It is the wrong thing to say. It is like saying “I probably won’t hit you with a shovel.” Suddenly everyone is afraid you will do the opposite.

“You must be worried sick” is what I said instead. “We would like to know all of the details of this case, so we can help you as quickly as possible.”

“Come in,” Zada or Zora said, and ushered us inside a room that at first seemed hopelessly tiny and quite dark. When my eyes adjusted to the dark, I could see that what had first appeared to be walls were large cardboard boxes stacked up in every available place, making the room seem smaller than it really was. The dark was real, though. It almost always is. The smell was stronger once the door was shut—so strong that my eyes watered.

“Excuse the mess,” said one of the aproned women. “The Knights were just packing up to move when this dreadful thing happened. Mr and Mrs Knight are beside themselves with worry.”

Zada’s and Zora’s eyes were watering too, or perhaps they were crying, but they led us through the gap between the boxes and down a dark hallway to a sitting room that appeared to have been entirely packed up and then unpacked for the occasion. A tall lamp sat in its box with its cord snaking out of it to the plug. A sofa sat half out of a box shaped like a sofa, and in two more open boxes sat two chairs holding the only things in the room that weren’t ready to be carried into a truck: Mr and Mrs Knight. Mr Knight’s chair was bright white and his clothes dark black, and for Mrs Knight it was the other way. They were sitting beside each other, but they did not appear to be beside themselves with worry. They looked very tired and very confused, as if we had woken them up from a dream.

“Good evening,” said Mrs Knight.

“It’s morning, madam,” said either Zada or Zora.

“It does feel cold,” Mr Knight said, as if agreeing with what someone had said, and he looked down at his own hands.

“This is S. Theodora Markson,” continued one of the aproned women, “and her apprentice. They’re here about your daughter’s disappearance.”

“Your daughter’s disappearance,” Mrs Knight repeated calmly.

Her husband turned to her. “Doretta,” he said, “Miss Knight has disappeared?”

“Are you sure, Ignatius dear? I don’t think Miss Knight would disappear without leaving a note.”

Mr Knight continued to stare at his hands, and then blinked and looked up at us. “Oh!” he said. “I didn’t realize we had visitors.”

“Good evening,” said Mrs Knight.

“It’s morning, madam,” said either Zada or Zora, and I was afraid the whole strange conversation was about to start up all over again.

“We’ve come about Miss Knight,” I said quickly. “We understand she’s gone missing, and we’d like to help.”

But Mr Knight was looking at his hands again, and Mrs Knight’s eyes had wandered off too, toward a doorway at the back of the room, where a round little man was gazing at all of us through round little glasses. He had a small beard on his chin that looked like it was trying to escape from his nasty smile. He looked like the sort of person who would tell you that he did not have an umbrella to lend you when he actually had several and simply wanted to see you get soaked.

“Mr and Mrs Knight are in no state for visitors,” he said. “Zada or Zora, please take them away so I can attend to my patients.”

“Yes, Dr Flammarion,” one of the aproned women said with a little bow, and motioned us out of the room. I looked back and saw Dr Flammarion drawing a long needle out of his pocket, the kind of needle doctors like to stick you with. I recognized the smell and hurried to follow the others out of the room. We made our way through a skinny hallway made skinnier by rows of boxes, and then suddenly we were in a kitchen that made me feel much better. It was not dark. The sunlight streamed in through some big, clean windows. It smelled of cinnamon, a much better scent than what I had been smelling, and either Zada or Zora hurried to the oven and pulled out a tray of cinnamon rolls that made me ache for a proper breakfast. One of the aproned women put one on a plate for me while it was still steaming. Anyone who gives you a cinnamon roll fresh from the oven is a friend for life.

“What’s wrong with the Knights?” I asked after I had thanked them. “Why are they acting so strangely?”

“They must be in shock from their daughter’s disappearance,” Theodora said. “People sometimes act very strangely when something terrible has happened.”

One of the aproned women handed Theodora a cinnamon roll and shook her head. “They’ve been like this for quite some time,” she said. “Dr Flammarion has been serving as their private apothecary for a few weeks now.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“Flammarion is a tall pink bird,” Theodora said.

“An apothecary,” continued the woman, more helpfully, “is something like a doctor and something like a pharmacist. For years Dr Flammarion worked at the Colophon Clinic, just outside town, before coming here to treat the Knights. He’s been using a special medicine, but they just keep getting worse.”

“That must have been very upsetting for Miss Knight,” I said.

Zada and Zora looked very sad. “It made Miss Knight very lonely,” one of them said. “It is a lonely feeling when someone you care about becomes a stranger.”

“So Miss Knight has no one caring for her,” Theodora said thoughtfully. The cinnamon rolls were the sort that is all curled up like a snail in its shell, and my chaperone had unraveled the roll before starting to eat it, so both of her hands were covered in icing and cinnamon. It was the wrong way to do it. She was also wrong about no one caring for Miss Knight. Zada and Zora were the ones who were beside themselves with worry. I leaned forward and looked first at Zada and then at Zora, or perhaps the other way around. And then, while my chaperone licked her fingers, I asked the question that is printed on the cover of this book.

It was the wrong question, both when I asked it and later, when I asked the question to a man wrapped in bandages. The right question in this case was “Why was she wearing an article of clothing she did not own?” but this is not an account of times when I asked the right questions, much as I wish it were.