Полная версия

Titanic: History in an Hour

TITANIC

History in an Hour

Sinead Fitzgibbon

About History in an Hour

History in an Hour is a series of ebooks to help the reader learn the basic facts of a given subject area. Everything you need to know is presented in a straightforward narrative and in chronological order. No embedded links to divert your attention, nor a daunting book of 600 pages with a 35-page introduction. Just straight in, to the point, sixty minutes, done. Then, having absorbed the basics, you may feel inspired to explore further.

Give yourself sixty minutes and see what you can learn . . .

To find out more visit http://historyinanhour.com or follow us on twitter: http://twitter.com/historyinanhour

Contents

Cover

Title Page

About History in an Hour

Introduction

The Battle for the North Atlantic

RMS Titanic: A Ship Unlike Any Other

The Maiden Voyage

An Inauspicious Beginning?

The Quest for Speed

Ice Warnings

A Catastrophic Error of Judgement

Damage Reports

To the Lifeboats

Save Our Souls!

Death by Drowning?

The Carpathia

Aftermath: Inquiries & Legacy

Mirror Images

Appendix 1: Key Figures

Appendix 2: Timeline of the Titanic Disaster

Copyright

Got Another Hour?

About the Publisher

Introduction

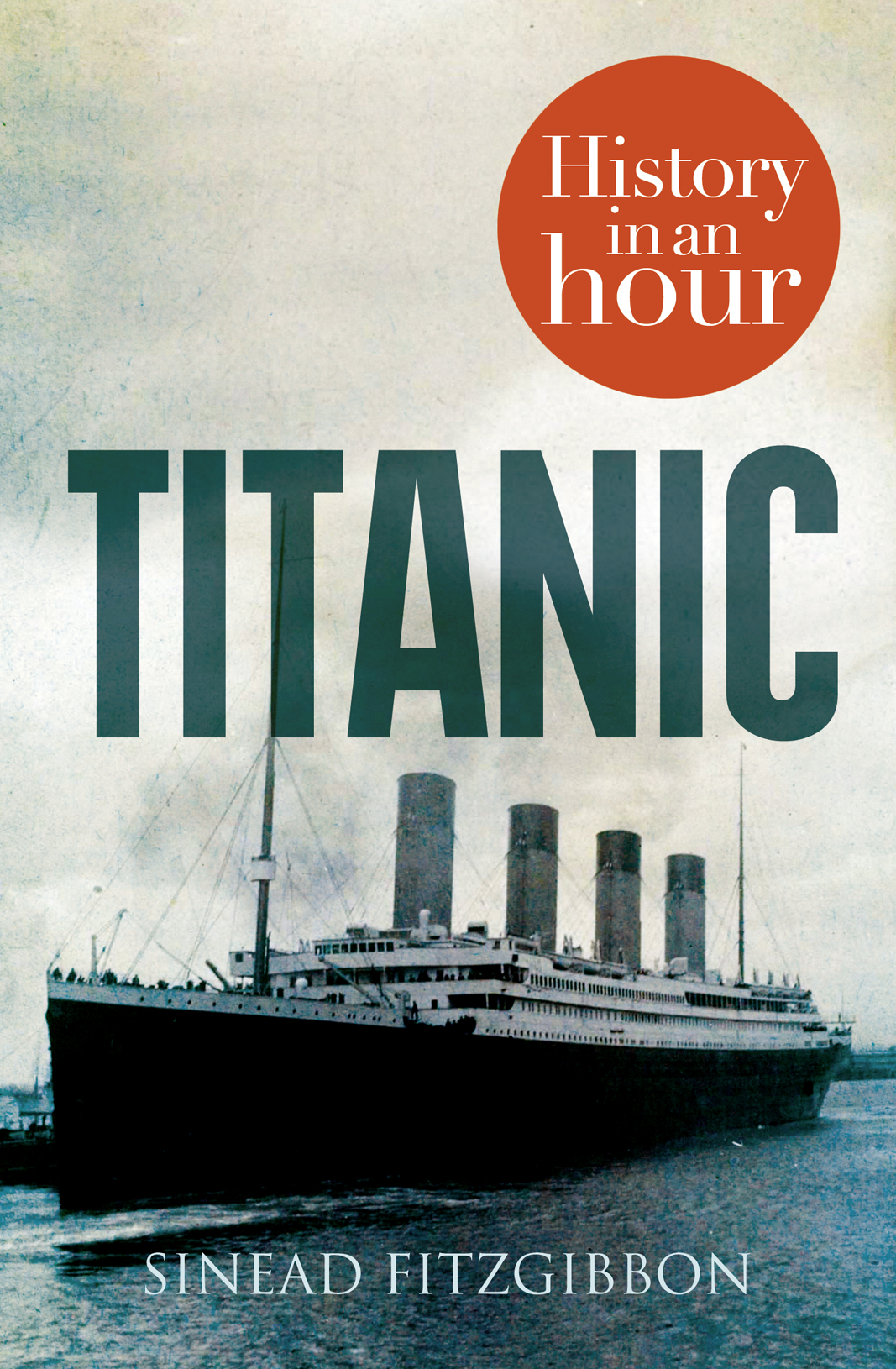

On Wednesday 10 April 1912, RMS Titanic embarked on her maiden voyage, carrying over 2,000 passengers, as she set sail from the port of Southampton, England, bound for New York City.

RMS Titanic was widely acknowledged to be the jewel in the crown of its owners, the White Star Line. The newly built liner was the product of the very latest advances in nautical engineering and a major achievement for its creators, Belfast shipbuilders, Harland & Wolff. It was the largest floating vessel the world had ever seen and, endowed as it was with every conceivable luxury, it was also the most opulent.

It is hardly surprising then, that the much-publicized launch of this gigantic vessel attracted intense media interest. On both sides of the Atlantic, Titanic was making headlines in national newspapers, while the cream of British and American high society, eager to bask in Titanic’s reflected glory, were lining up to book a passage on her maiden voyage.

Much of the excitement which accompanied Titanic’s unveiling was based on the expectation that it would smash the transatlantic speed record, previously held by the Mauretania, which was owned by White Star’s arch-rivals, the Cunard Line. This quest for speed did indeed see RMS Titanic sailing into the pages of history but, tragically, for all the wrong reasons.

Sadly, for her approximately 2,000 awe-struck passengers and crew, Titanic was not destined to reach its final destination. Four days into the week-long voyage, this triumph of human ingenuity and engineering struck a large iceberg in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. In just over two hours, she had descended to her watery grave on the ocean floor, with the loss of over 1,500 lives.

This is the story of how, thanks in large part to a calamitous chain of unfortunate events combined with a litany of human errors, the maiden voyage of a supposedly ‘unsinkable’ ship became one of the worst maritime disasters in peacetime history.

This is the story of RMS Titanic.

The Battle for the North Atlantic

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, transatlantic sea travel was fast becoming a lucrative business. Passenger numbers were on the increase, thanks in large part to the hordes of émigrés leaving Europe in search of a better life in America, while steamships also profited by ferrying mail between the US and Britain.

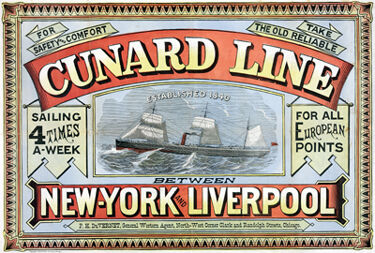

Since its owner, Samuel Cunard, was awarded the first British transatlantic mail contract in 1839, the Cunard Line had operated a near-monopoly on this highly profitable route.

Cunard Line Poster, 1875

This all changed, however, when Thomas Ismay purchased the White Star Line in 1869. Operating in direct competition with the Cunard Line, the White Star Line’s entry into the transatlantic market marked the beginning of a decade-long battle between the two companies as they vied for dominance of the Atlantic Ocean. To complicate matters, they were also fighting off stiff competition from emergent shipping firms from Germany. The stakes could not have been higher.

By 1907, with the impending maiden voyage of their new liner, the Lusitania, Cunard seemed to be once again gaining the upper hand. The Lusitania was the first in a new generation of superliners, and was soon joined by a sister steamship, the Mauretania, which was also nearing completion. Weighing approximately 30,000 gross tonnes and with a length of 790 feet, the Lusitania and the Mauretania were larger and more luxurious than any of their predecessors. They were also to be the fastest. It was widely expected that the Blue Riband – the award given to the fastest ship to cross the Atlantic – would go to either one or the other.

White Star Line Logo

Unsurprisingly, executives at the White Star Line were coming under increasing pressure to catch up with Cunard.

The White Star Line makes a Comeback

The White Star Line was now part of the American financier J. P. Morgan’s conglomerate of shipping companies, known as International Mercantile Marine. J. Bruce Ismay, who had succeeded his father at the helm of White Star in 1899, had sold the company to Morgan (pictured below) in 1902 on the understanding that he stayed on as Chairman and Managing Director. Thus, with almost limitless financial resources from his über-wealthy investor, the younger Ismay set about plotting White Star’s comeback.

J. P. Morgan

In the summer of 1907, Ismay and his wife attended a dinner at the London home of Lord and Lady Pirrie. A partner in the Belfast shipbuilding firm Harland & Wolff, Pirrie’s business relied heavily on the White Star Line for new ship-building contracts, so he had a vested interest in the continuing success of Ismay’s company. It is widely believed that over the course of this dinner the two men concocted an audacious plan to regain the advantage over the Cunard Line.

With the cavalier attitude of those spending someone else’s money, Pirrie and Ismay (pictured together below) decided that Harland & Wolff would build three state-of-the-art ships for the White Star Line. The new liners would be gigantic – at least 50 per cent larger and 100 feet longer than both the Lusitania and the Mauretania. They would offer passengers unparalleled luxury and comfort.

Pirrie and Ismay on board the Titanic Photograph by Robert John Welch (1859–1936), official photographer for Harland & Wolff

Suitable names were needed for these sister ships, names which would be commensurate with their size and grandeur – they settled on the Olympic, the Titanic and the Britannic.

The Building of a Leviathan

After this initial dinner meeting, Pirrie and Ismay quickly set to work. The proposed ships would be so huge that Harland & Wolff would need to overhaul their entire operation in order to accommodate them. The shipyards at Harland & Wolff underwent a significant re-vamp, which involved converting their three existing berths into two, over which a 220-foot-high gantry was installed. For his part, Ismay set about lobbying the New York Harbour Board for permission to build a new pier, large enough to berth his monstrous new vessels. Pirrie’s designs were endlessly debated, while Ismay encountered difficult negotiations with the Harbour Board.

By the end 1908, as an agreement with the New York authorities looked likely and the ship’s blueprints were finalized, work could at last get underway. It was decided that the Olympic and the Titanic would be constructed almost in tandem, with plans for the building of the Britannic put on hold until after the completion of her sister ships. On 16 December, the first keel plate was laid for the Olympic, with Titanic’s following three months later, on 31 March 1909.

White Star Line Promotional Poster

The process of building a ship is a complicated one. First, the hull (the lower part of the vessel) is constructed in a dry berth. Once completed, the hull (still no more than an empty shell) is ‘launched’ down a ramp into water. It is then towed to a fitting-out basin, where all the necessary equipment, machinery, fixtures and fittings are installed. When it is entirely kitted-out, the ship returns to a dry dock, where the propellers are attached. Then, after one last coat of paint, the gleaming new ship is tugged into harbour and handed over to its proud owners.

Even though Harland & Wolff devoted innumerable man-hours to the construction of the Olympic and the Titanic, the sheer scale of the undertaking meant the hulls would not be completed for nearly two years. Eventually, on 20 October 1910, the Olympic was launched from her berth (pictured below). While this was cause for great excitement, all eyes were on another, more significant, milestone, which was scheduled for 31 May of the following year.

Titanic and Olympic under construction c. 1910

In a move to capitalize on the inevitable public interest in these new superliners, Harland & Wolff had arranged for the launch of Titanic’s hull to occur on the same day they handed over the newly fitted-out Olympic to the White Star Line. This meant that the partially completed Titanic would sit alongside her sister ship in water for the very first time. This guaranteed unparalleled media interest in the Olympic and Titanic, and consequently, Harland and Wolff sold thousands of tickets to the event. On the day, hordes of spectators joined distinguished dignitaries on three specially constructed grandstands – all eager to witness this historic moment.

At exactly 12.05 p.m., two loud rockets were fired, followed by another five minutes later. Thus heralded, at 12.13 p.m. Titanic’s hull began to make its way down the greasy slipway and into water for the first time. The displacement of such a large structure was made possible by greasing the ramp with huge quantities of lubricant – 23 tonnes of animal fat, soap and train oil. The launch lasted 62 seconds, and the RMS Titanic was afloat at last.

At 3.00 p.m. the same day, Harland & Wolff formally delivered the Olympic to the White Star Line, after which the Olympic got her first taste of the sea, setting sail for Liverpool with Morgan, Ismay and a host of other illustrious names on board. The ambitious dreams of J. Bruce Ismay and Lord Pirrie had finally become reality.

RMS Titanic: A Ship Unlike Any Other

While the Olympic sailed for England, Titanic took her place in the fitting-out basin. The installation of machinery, equipment and fixtures was a painstaking process, which would take ten months and several million man-hours to complete.

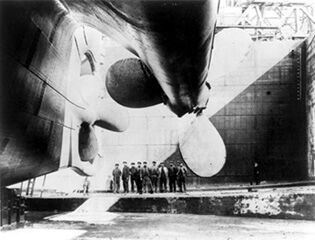

Titanic was furnished with twenty-nine massive boilers and three engines, which were serviced by four huge smokestacks or funnels. This state-of-the-art machinery allowed for an almost unprecedented top speed of 22.5 knots (or nautical miles per hour), which was also no doubt assisted by her three gigantic propellers, the largest of which measured 23.5 feet in diameter and weighed around 15 tonnes. So gigantic were the propellers (pictured below) a team of twenty horses was employed to pull them from the workshop prior to fitting.

Titanic’s Giant Propellers, at the Harland & Wolff shipyard 31 May 1911 Photograph by Robert John Welch (1859–1936), official photographer for Harland & Wolff

As RMS Titanic slowly began to take shape, it became clear that she would outshine even the Olympic. Although almost identical in design, the Titanic was a full 1,004 tonnes larger than her elder sibling. At 882.75 feet in length and 92 feet in width, her dimensions were indeed awe-inspiring. With her four funnels in place, her height was measured at a staggering 175 feet, and her weight was a massive 46,000 tonnes. At full capacity, she could accommodate 2,600 passengers and a crew of 940.

The sheer scale of the new ship was conveyed in an article in the Southampton Pictorial, its author having viewed the berth in Southampton, prior to her maiden voyage.

Perhaps the most striking features of the great inert mass of metal are the four giant funnels – huge tawny brown and black capped elliptical cylinders of steel, dominating the other shipping in the port and dwarfing into insignificance the sheds on the quayside.

RMS Titanic, it seemed, was certainly worthy of her name.

In a Class of its Own

If Titanic looked impressive from the outside, her interior appointments were even more extraordinary. The first-class areas of the ship were showcases of Edwardian splendour. Not one, but two staircases curved down from the upper to the lower first-class decks. One, known as the Grand Staircase was positioned near the front of the ship (forward) and the other towards the back (aft). The Olympic’s forward staircase – identical to Titanic’s – is pictured below.

Both stairways boasted elaborately carved wooden banisters and beautiful wrought-iron balustrades. An exquisitely decorated clock, set into an ornate wooden panel, was placed on the landing at the top of the front staircase. The walls were lined with polished oak panelling inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and these were illuminated by a flood of natural light which streamed through the huge glass dome crowning the forward staircase. Ornate gold-plated light fixtures glittered from the ceilings at night.

Forward Grand Staircase on the RMS Olympic

The first-class dining saloon was yet another sight to behold. Measuring over 100 feet in length, with tall alcoves housing arched and leaded windows, it was by far the largest room on the ship. It would become the hub of evening social activities during the fateful maiden voyage. If passengers grew tired of the oversized dining room, however, the Verandah Café with its ivy-covered trellises, and the Café Parisien (pictured below) complete with genuine French waiters, offered a more intimate dining experience.

Titanic’s Café Parisien Photography by Robert John Welch, official photographer for Harland & Wolff

Other amenities offered to first-class passengers on RMS Titanic included a reading and writing room, which was stocked with an impressive library (pictured below). Enclosed promenade decks allowed for exercise even in inclement weather, along with a large swimming pool, and a well-equipped gymnasium. There were also some decadent Turkish Baths and a barber shop.

Reading Room for First-Class Passengers

One first-class passenger, Mrs Ida Strauss – wife of Isidor Strauss, the founder of Macy’s department store – described her first impressions of the Titanic in a letter to a friend: ‘But, what a ship! So huge and so magnificently appointed. Our rooms are furnished in the best of taste and most luxuriously and they are really rooms, not cabins.’

It was not just the first-class accommodation that was impressive, somewhat unusually for the time, second- and third-class passengers also travelled in style. While nowhere near the ostentatious magnificence of first class, Titanic’s second- and third-class areas were still a considerable improvement on the norm. As a rule, the second-class accommodation on Titanic was equivalent to first class on other ships, while third class equated to second class on other liners.

Lawrence Beesley, a teacher and one of the few second-class male passengers lucky enough to survive the disaster, described the ship in detail in a letter to his son:

The ship is like a palace! There is an uninterrupted deck run of 165 yards for exercise and a ripping swimming bath, gymnasium and squash racket court & huge lounge & surrounding verandahs. My cabin is ripping, hot and cold water and a very comfy looking bed and plenty of room.

Similarly, another second-class passenger, 31-year-old Harvey Collyer, wrote to his parents:

So far we are having a delightful trip the weather is beautiful the ship magnificent . . . It’s like a floating town. I can tell you we do swank we shall miss it on the trains as we go third on them. You would not imagine you were on a ship. There is hardly any motion she is so large we have not felt sick yet.

All in all, it seems that to travel on RMS Titanic was to travel in unprecedented comfort, regardless of the class of ticket.

The Maiden Voyage

At the end of March 1912, RMS Titanic’s fit-out was complete and she was finally ready for service. Harland & Wolff formally handed the ship over on 2 April to the White Star Line. She set sail from Belfast bound for the port of Southampton on England’s south coast, arriving just after midnight on 3 April 1912.

With her maiden voyage scheduled to leave at noon on 10 April, the intervening week saw a frenzy of activity as this titan of the sea was stocked with a mountain of supplies for her week-long expedition. The provisioning of such a vast ship was no small task – an endless stream of linens, crockery, cutlery, food, drink, coal, even ice and fresh-cut flowers was ferried into the cavernous vessel from morning to night. Absolutely no expense was spared.

Similarly, the White Star Line was not about to settle for anything less than the best when it came to selecting the crew for Titanic’s maiden voyage. With the eyes of the world fixed on their wondrous new ship, it comes as no surprise that the White Star Line entrusted Titanic to their most able and senior seaman, Captain Edward J. Smith (pictured below).

Captain Edward J. Smith

Captain Smith had enjoyed a long and distinguished career with Ismay’s company. Since being promoted to the rank of Commodore of the White Star Line in 1904, he routinely took to the helm of their newest and grandest ships. The 62-year-old Smith’s seafaring career was, however, drawing to a close. This was to be his last voyage before retirement – and what better way to round off a glittering career than to take command of the world’s largest passenger liner?

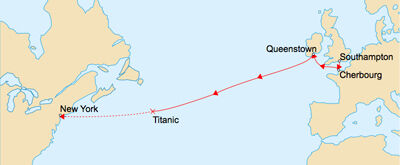

The course plotted for Titanic’s maiden voyage was one that had been followed many times by other transatlantic liners. After leaving Southampton, she was to sail to Cherbourg in Northern France, and then on to Queenstown (now Cobh) in Co. Cork on the southern coast of Ireland. After Queenstown, Titanic would put out into the great Atlantic Ocean, next stop New York.

The Route Plotted for Titanic’s Maiden Voyage

An Illustrious Gathering

In the days leading up to Titanic’s scheduled departure date, hundreds of passengers who had succeeded in booking passages on her maiden crossing began to converge on Southampton, Cherbourg and Queenstown.

Unsurprisingly for such a luxurious liner, the first-class passenger list was impressive, reading as a veritable who’s who of British and American high society. Among the American passengers were: New York tycoon, John Jacob Astor and his pregnant young wife, Madeleine (pictured below); the millionaire businessman Benjamin Guggenheim who was accompanying his mistress, the French singer, Ninette Aubart; the brash and generally unpopular Denver society hostess, Molly Brown; Isidor Strauss, the founder of Macy’s department store, and his wife, Ida; George D. Widener, said to be the richest man in Philadelphia, along with his wife and son; and Major Archibald Butt, military attaché to the President of the United States.

J. J. Astor and his wife, Madeleine

The British contingent was equally well-heeled. Distinguished passengers included Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon, a Scottish landowner, and his fashion-designer wife, Lady Lucy Duff-Gordon; William T. Stead, the social activist, philosopher and editor of London’s Review of Reviews; and the Countess of Rothes, who was travelling to California to join her husband, the Earl of Rothes, who was on a land-buying expedition on America’s West Coast.

Other notable passengers included J. Bruce Ismay, whose tenacity and vision were responsible for bringing RMS Titanic to life; the American tennis player and Wimbledon champion, Karl Behr; silent movie star, Dorothy Gibson, and the famous Broadway producer, Jacques Futrelle.

Interestingly, the owner of the White Star Line and Titanic’s chief investor, J. P. Morgan, was forced to abandon his plans to sail on his new ship due to business commitments – a last-minute change of mind which may very well have saved his life.

But this was not the only eleventh-hour change of plan for RMS Titanic’s maiden voyage . . . there was a second, which would prove to be far less propitious for those involved.

Crew Changes

Just as Titanic was preparing to set sail, her sister ship, the Olympic, was forced to return to the Harland & Wolff shipyards for emergency repairs to a propeller. This unexpected turn of events led to a surprise re-shuffle of Titanic’s crew not long before the ship’s scheduled departure.