Полная версия

The Hitler–Hess Deception

It was during this period that Hitler developed hopes that some form of accommodation could be found to end the conflict, with Germany retaining her conquests, and the Allies, having made their protests and metaphorically waved their fists at a belligerent Germany, backing down and agreeing to peace.

On 6 October, the fighting in Poland having finished and there being only a minimal level of conflict in the west, Hitler made his first public appeal for peace, giving an unrepentant yet placatory speech to the Reichstag. To many in the west, Hitler’s speech sounded like mere rhetoric. But, unbeknownst to the Reichsleiters and Reichsministers seated before him, the Führer had been making a concerted behind-the-scenes effort to negotiate an accord with Britain.

Ten days prior to Hitler’s appearance at the Reichstag, he had had a confidential meeting in his office at the Chancellery with a man named Birger Dahlerus, a prominent Swedish businessman who was also a close friend of the British Ambassador in Oslo, Sir George Ogilvie Forbes. Dahlerus informed Hitler that Ogilvie Forbes had told him that ‘the British government was looking for peace. The only question was: How could the British save face?’

‘If the British actually want peace,’ Hitler had replied, ‘they can have it within two weeks – without losing face.’9 He informed Dahlerus that although Britain would have to be reconciled to the fact that ‘Poland cannot rise again’, he was prepared to guarantee the security of Britain and western Europe – a region he had little interest in, for despite some concerns about German access to the North Sea, German expansion into western Europe was not part of the Karl Haushofer plan for the Greater Germany.

Also present at this confidential meeting with Dahlerus was Hermann Göring, who suggested that British and German representatives should meet secretly in Holland, and that if they made progress, ‘the Queen [of Holland] could invite both countries to armistice talks’. Hitler finally agreed to Dahlerus’s proposal that he ‘go to England the very next day in order to send out feelers in the direction indicated’.

‘The British can have peace if they want it,’ Hitler told Dahlerus as he left, ‘but they will have to hurry.’10

Now, ten days later, Hitler stood before the Reichstag and proclaimed Germany’s justification for taking back her former territories from Poland. For over an hour he discoursed on the history of the region that had led to the present state of affairs. Then, having taken this belligerent position, so that any placatory utterances he now made would not be seen as weakness, Hitler began to make his overtures for peace. First, he declared:

My chief endeavour has been to rid our relations with France of all trace of ill will and render them tolerable for both nations … Germany has no claims against France … I have refused even to mention the problem of Alsace-Lorraine … I have always expressed to France my desire to bury forever our ancient enmity and bring together these two nations, both of which have such glorious pasts.

He then went on to speak about his greater cause for concern:

I have devoted no less effort to the achievement of Anglo–German understanding, nay, more than that, of an Anglo–German friendship. At no time and in no place have I ever acted contrary to British interests. I believe even today that there can only be real peace in Europe and throughout the world if Germany and England come to an understanding … Why should this war in the west be fought? … The question of re-establishment of the Polish state is a problem which will not be solved by war in the west but exclusively by Russia and Germany.

After touching on a whole range of European problems that would in the end, Hitler felt, have to be resolved at the conference table, not on the battlefield, including the ‘formation of a Polish state’, Germany’s colonies, the revival of international trade, ‘an unconditionally guaranteed peace’, and a settlement of ethnic questions in Europe, Hitler proposed that a conference should be arranged to ‘achieve these great ends’. He concluded:

It is impossible that such a conference, which is to determine the fate of this continent for many years to come, could carry on its deliberations while cannon are thundering or mobilised armies are bringing pressure to bear upon it. If, however, these problems must be solved sooner or later, then it would be more sensible to tackle the solution before millions of men are first uselessly sent to death and billions of riches destroyed.

One fact is certain. In the course of world history there have never been two victors, but very often only losers. May those peoples and their leaders who are of the same opinion now make their reply. And let those who consider war to be the better solution reject my outstretched hand …11

The following morning the Nazi Party mouthpiece, the Völkischer Beobachter newspaper, blared the headlines:

GERMANY’S WILL FOR PEACE.

NO WAR AIMS AGAINST FRANCE AND ENGLAND –

NO MORE REVISION CLAIMS EXCEPT COLONIES –

REDUCTION OF ARMAMENTS – CO–OPERATION WITH

ALL NATIONS OF EUROPE – PROPOSAL FOR A

CONFERENCE.12

The olive branch had been proffered. Would it be taken up?

There followed nearly a week’s stony silence from Britain and France, prompting the German Führer to once again officially announce his ‘readiness for peace’ in a brief address at Berlin’s Sportpalast. ‘Germany,’ he declared, ‘has no cause for war against the Western Powers.’13

On 12 October 1939, Neville Chamberlain finally responded to Hitler’s offer, terming his proposals ‘Vague and uncertain’, and making the comment that ‘they contain no suggestions for righting the wrongs done to Czechoslovakia and Poland’. No reliance, Chamberlain asserted, could be put on the promises of ‘the present German government’. After the humiliating defeats of Munich and Hitler’s move against Poland, Britain’s Prime Minister now suddenly exhibited a strength few thought him capable of. If Germany wanted peace, ‘acts – not words alone – must be forthcoming’, and he called for ‘convincing proof’ from Hitler that he really wanted an end to the conflict.

The following day, 13 October, Hitler responded by issuing a statement which declared that Chamberlain, in turning down his earnest proposals for peace, had deliberately chosen war. Such was the public face of the events at the time.

Yet what about the private face? What about the travels of Mr Dahlerus, which few people in Britain, including the House of Commons, ever got to hear about?

It was one thing for Chamberlain to turn down some airy peace proposal made by Hitler, presumably aimed at home consumption. In the world of diplomacy, much more credence would have been given to such a proposal if it had been made in writing, or delivered by an official emissary. It is not suggested that peace would have suddenly erupted on the receipt of an official communiqué more clearly outlining Germany’s peace proposal – but it would certainly have been a starting point, from which an accord approaching the Allied demands could have been discussed, even if those negotiations subsequently failed.

Incredibly, such a communiqué is exactly what the British government, in the form of Neville Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, had secretly received as far back as August 1939.

In the spring of 1941, Hjalmar Schacht, the head of Germany’s Reichsbank, approached the then non-combatant American government to ask if they would be prepared to act as intermediaries to help negotiate a peace between Germany and Britain. Soon a positive flurry of urgent memos were flying between Foreign Office mandarins in Whitehall querying what should be done, for they were not at all keen for America to interfere in Britain’s foreign policy decisions. Eventually the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, Sir Alexander Cadogan, sent a ‘most secret’ memorandum to Lord Halifax, who was by then British Ambassador in Washington, that stated:

Many thanks for your letter of 17th June about Schacht’s peace feeler.

We recently prepared for our own use a memorandum summarising the various peace feelers which have reached us since the beginning of the war. The Germans are obviously now attempting to interest certain circles in the USA in the possibility of an early peace … It therefore occurred to us that you might like to see a copy of this memorandum and to communicate it very confidentially to the President for his own personal and secret information. In suggesting that you should do this we do not mean to suggest for a moment that the President is in any need of advice as to how to handle any such German approaches, but he may find details of our own experiences useful in helping him to handle the ‘weaker brethren’ in the USA … 14

The memorandum then went on to disclose details of sixteen peace attempts that had been made by the Germans since the outbreak of war. These included the Dahlerus peace initiative, about which it was revealed: ‘[Dahlerus] was convinced that Göring genuinely regretted the outbreak of the war and short of actual disloyalty to Hitler would like to see a truce negotiated. The unwillingness of the Polish government to treat in earnest about Danzig and The Corridor, coupled, perhaps, with deliberate malice on the part of Ribbentrop, had unleashed the conflict.’15 The memorandum went on to explain that on 18 September 1939 a confidential meeting had taken place in London between high-ranking officials of the Foreign Office, including Cadogan, and Dahlerus, who ‘reported that the German army were now approaching a position in Poland beyond which they would not go and that the German government were seeking an early opportunity to make an offer of peace.’16

At this meeting Dahlerus was informed that the British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax ‘could conceive of no peace offer likely to come from the German government that could even be considered … and that the British government could not … define their attitude to an offer of which they did not know the nature’.

On 12 October 1939, the report went on, Dahlerus had transmitted the final details of Germany’s very comprehensive peace offer. These included the information that Hitler was prepared to discuss the Polish situation, non-aggression pacts, disarmament, colonies, economic questions and frontiers. Indeed, Dahlerus even communicated that ‘Hitler had taxed the patience of the German people over the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Poland, and that if Göring, as the chief negotiator, secured peace, Hitler could not risk acting counter to these national undertakings.’17

This comprehensive peace initiative was kept secret in both Germany and Britain. However, even while admitting these details for ‘President Roosevelt’s Eyes Only’ in 1941, the British government was still sensitive enough about the subject to conceal certain details about what had taken place. To the uninitiated, Dahlerus’s efforts at peace in 1939 appeared a damp squib that had fizzled out. Yet there had been much more to them than the British government was prepared to admit to the American President.

During 1938, Neville Chamberlain had, with much effort, negotiated comprehensive deals with Hitler. Hitler, however, had shown a dangerous penchant for negotiating agreements and then reneging on them as soon as it suited his purposes. He wasn’t, as one diplomat later remarked, a gentleman. Chamberlain had therefore, not unnaturally, developed a marked sensitivity about being seen to negotiate again with the Nazis, whilst at the same time exhorting the British people to prepare themselves to make great sacrifices. Thus the report to Roosevelt, at a time when America was still neutral and Britain could not afford even to hint at the possibility of negotiating with the Nazis, for fear of losing American support, concealed the fact that Dahlerus had been involved in Hitler’s attempts to prevent war before the conflict had started. As consummate politician and diarist, close friend of Britain’s high and mighty, Sir Henry ‘Chips’ Channon commented two days before Germany’s invasion of Poland, on 28 August 1939: ‘Mr D[ahlerus] and a Mr Spencer have it appears been negotiating secretly here … I doubt the validity of the Walrus’s [Dahlerus’s] credentials, but he is taken seriously by Halifax, and a secret plane transported the two emissaries here, with special facilities at the airport.’18

Exactly one month later, on 28 September, Channon recorded that Dahlerus, having been to Berlin to consult with Hitler, was back in London for another secret meeting – a meeting that would not be mentioned in the information released to Roosevelt: ‘Very Secret. “The Walrus” is in London. He arrived today by plane and this time his visit is known to Hitler. Halifax and others are seeing him this afternoon. No-one knows of this. What nefarious message does he bring?’

The following day, Channon noted:

The fabulously mysterious ‘Walrus’ … was interviewed secretly yesterday … This morning he walked about the Foreign Office openly. Also Cadogan had a talk with him and a report of their conversation was given to Lord Halifax, who read it I believe, at the War Cabinet … The French, always realistic, say ‘we had better make peace as we can never restore Poland to its old frontiers, and how indeed should we ever dislodge the Russians from Poland even if we succeeded in ousting the Germans?’19

However, in the atmosphere of diplomatic and international distrust that had developed by October 1939, British contemplation of negotiating peace with Hitler quickly began to evaporate. Dahlerus’s initiative failed, and the war continued unabated.

This, however, did not mean that Hitler gave up on the idea, and he continued secretly trying to find a negotiated end to the simmering conflict in the west before it came to the boil, ruining his timetable for eastern conquest. In truth he had no choice. He had found himself fighting the wrong war.

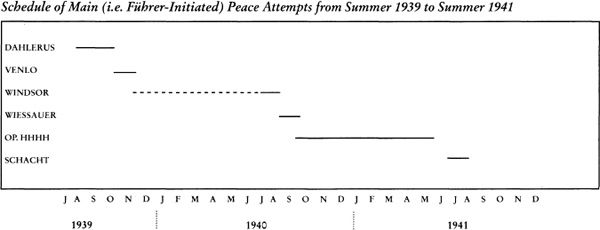

This situation led, between the summers of 1939 and 1941, to the British government receiving a great many German peaceable approaches. A substantial number of these can be discounted, for they included such low-level attempts as the German Chargé d’Affaires in Washington contacting the British Ambassador to inform him that ‘if desired he could obtain from Berlin Germany’s present peace terms’.20 On another occasion the British Legation to the Holy See reported that the Vatican would be prepared to arbitrate between Britain and Germany ‘through the Apostolic Delegate on the subject of Germany’s peace offer’.21

Indeed, reports on the possibilities of peace were submitted back to London from far and wide – even from distant Angora, where Ambassador Sir Hugh Knatchbull-Hugessen reported that the ‘Netherlands Minister has sent me the following information regarding a conversation between Herr von Papen and Herr Hitler during the former’s recent visit to Berlin’. He went on to tell his seniors at the Foreign Office that ‘Herr Hitler discussed [with von Papen his] possible terms of peace’.22

Each one of these reports required the attention of an Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office and the creation of its own file, and so became counted in the plethora of peaceable attempts made to the British government by German nationals or well-meaning neutrals. There were so many of these little snippets of peaceable intent that the whole matter of peace in 1939, 1940 and 1941 becomes rather a jumble, and to a large extent the important – real – peaceable moves made at this time have become hidden amongst all these lesser ones. However, it is possible to refine the plethora of peaceable initiatives down to just a few nuggets of gold – those that were stamped with the hallmark of Hitler.

There were basically three distinct strata to the peaceable attempts. The vast majority were low-level suggestions made by neutrals, junior German diplomats or the odd German official at loose in a neutral state. The second stratum, which was of some interest to the Foreign Office, emanated from respected neutrals, such as the King of Sweden, and upper-echelon German nationals, such as former War Minister Otto Gessler and even top Nazis such as Goebbels. These pitches for peace were made with an eye to the credit that would accrue to their originators, particularly with Hitler, if they brought Germany peace.

There was however, a third stratum of peaceable attempts, and these were of a different ilk altogether. They were top-grade offers that received the personal attention of the Foreign Secretary, and frequently the Prime Minister as well. Furthermore, there were occasions when these attempts were of such importance that they required the Prime Minister to consult the dominion heads of government in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa before they could be rejected.

The most intriguing fact about these top-grade offers is not only that they clearly emanated from Adolf Hitler himself, transmitted to the British authorities through his own personal emissaries, but that there was a discernible pattern to them. As each attempt failed or began to flounder, a new one was immediately initiated through another avenue to replace it, thereby creating an almost unbroken chain of peaceable attempts from the summer of 1939.

It was a situation that caused much interest and speculation within Britain’s Foreign Office and Intelligence Services. By the summer of 1940 it was realised that these secret Hitler-initiated attempts at peace mediation revealed a psychological flaw deep within the Führer’s character that Britain could, with skill and guile, exploit to Germany’s disadvantage.

Even as it became clear to Hitler that Birger Dahlerus’s attempts at mediation in September-October 1939 would fail, moves began to open another channel to the British government. However, the German Führer was still a relative novice at the art of opening secret lines of communication to Britain’s leadership, and rather than stepping back to assess the situation, calling upon expert advice before dispatching an eminent diplomat or well-respected neutral, he accepted the services of the SS. That was not a good idea.

On 17 October 1939 SS Colonel Walter Schellenberg was summoned to a meeting with the head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), Reinhard Heydrich, at RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt – the Directorate General of Security for the Reich) headquarters on Prinz Albrechtstrasse in Berlin – a building it shared with the Gestapo, which reveals much about the RSHA’s interests. Ushered into the presence of this extremely dangerous man, second only to Himmler in the SD–SS chain of command, Schellenberg was surprised to find Heydrich in congenial mood. ‘For several months,’ Heydrich confided, ‘one of our agents in the Low Countries … has been in contact with the British secret service.’23 He went on to inform Schellenberg that this agent, a man named Morz, had made several important contacts with British Intelligence, including two agents based in Holland. These were Major Richard Stevens, the Passport Control Officer at the British Embassy in The Hague (all Passport Control Officers were members of Britain’s intelligence service MI6, better known as SIS), and Captain Sigismund Payne-Best, who ran the Z Network in Holland (an intelligence-gathering unit which reported to Passport Control Officers). Schellenberg’s orders were to use these two men to ‘get in touch with the English government’24 in order to initiate Anglo–German peace negotiations.

Within a few days of his meeting with Heydrich, Schellenberg found himself in Holland, under the alias of Captain Schaemmel of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) Transport Service, pretending to Stevens and Payne-Best that he represented a group of leading Wehrmacht officers who wanted peace. This pretence was almost certainly adopted not only to protect Heydrich and Himmler should anything go wrong, but also because the British would have blanched at finding themselves negotiating with the SS. Schellenberg offered the very tempting bait that his faction might even be prepared to accept conditions that limited Hitler’s position within Germany, although he stressed that it was desirable that Hitler remained head of state – which in Nazi terms meant that in public Hitler would have remained the German head of state in a purely ceremonial capacity, while in private he continued in charge. This curious suggestion was not as improbable as it might first appear, for the SS was all-powerful in Nazi Germany, and Himmler secretly harboured great ambitions for it, planning that it would eventually supplant the Nazi Party as the controlling power in Germany.

Within hours of his meeting with Schellenberg, Stevens dispatched a ‘most secret’ telegram to London, putting forward the German peace proposals and relating the remarkable suggestions concerning Hitler’s future status. He soon received a reply that stated:

In the event of the German representatives enquiring whether you have had a reply to the questions which you said … you would refer to H.M.G., you should inform them as follows (not, however, handing them anything in writing):-

Whether Hitler remains in any capacity or not (but of course more particularly if he does remain) this country would have to see proof that German policy had changed direction … Germany [would not only] have to right the wrongs done in Poland and Czechoslovakia, but she would also have to give pledges that there would be no repetition of acts of aggression …25

The message concluded:

It is not for H.M.G. to say how these conditions could be met, but they are bound to say that, in their view, they are essential to the establishment of confidence on which alone peace could be solidly and durably based …

Neither France nor Great Britain, as the Prime Minster said, have any desire to carry on a vindictive war, but they are determined to prevent Germany continuing to make life in Europe unbearable.26

On receiving the bulk of this communication via Stevens, Schellenberg promptly reported to Heydrich: ‘The British officers [have] declared that His Majesty’s Government took great interest in our attempt which would contribute powerfully to prevent the spread of war … They assured us that they were in direct contact with the [British] Foreign Office and Downing Street.’27 He concluded by informing Heydrich that the British had invited him to secret peace negotiations in London, and that Stevens had even given him a transmitter (call sign ON4) with which he could covertly contact the British directly.

Heydrich’s response was most interesting, indicating that there was a great deal more going on behind the scenes than Schellenberg ever knew about. ‘All this seems to me a little too good to be true,’ the head of the SD commented. ‘I find it hard to believe that it’s not a trap. Be very careful going to London. Before making a decision I shall have to talk not only with the Reichsführer [Himmler] but more particularly with the Führer. Wait for my orders before proceeding.’28 Evidently from the German side the negotiations emanated from the pinnacle of Nazi government.

Events, however, were about to take a bizarre and unexpected twist. In distant Munich, on the night of Wednesday, 8 November, there was an attempt on Hitler’s life when a bomb blew up the Bürgerbräukeller just twenty minutes after he had cut short a speech and unexpectedly departed early. Outraged that this assassination attempt might have been prompted by the British, the SD took immediate action.

The very next afternoon, Stevens and Payne-Best, who were waiting to meet Schellenberg at the little Dutch–German frontier post at Venlo, were kidnapped by SD agents who dashed across the border, shot up the Dutch customs post, grabbed the two startled British Intelligence officers and made off with them across the frontier into Germany. Stevens and Payne-Best were intensively interrogated by German Intelligence, and after the German conquest of the west in 1940 the whole of Britain’s secret service network in western Europe would be brought crashing down, leaving it with virtually no intelligence-gathering assets. On the German side, the Venlo Incident, as it became known, ended any possibility of Schellenberg negotiating an end to the war.