Полная версия

The Afghan Wars: History in an Hour

THE AFGHAN WARS

History in an Hour

Rupert Colley

About History in an Hour

History in an Hour is a series of ebooks to help the reader learn the basic facts of a given subject area. Everything you need to know is presented in a straightforward narrative and in chronological order. No embedded links to divert your attention, nor a daunting book of 600 pages with a 35-page introduction. Just straight in, to the point, sixty minutes, done. Then, having absorbed the basics, you may feel inspired to explore further.

Give yourself sixty minutes and see what you can learn . . .

To find out more visit http://historyinanhour.com or follow us on twitter: http://twitter.com/historyinanhour

Contents:

Cover

Title Page

About History in an Hour

Introduction

The First Anglo-Afghan War

The Second Anglo-Afghan War

The Third Anglo-Afghan War

The ‘Saur’ Revolution

The Communist Era

The Soviet War in Afghanistan

The Afghan Civil War

The Taliban

Afghanistan under the Taliban

9/11

The Afghanistan War

The Taliban Insurgency

The Death of Bin Laden

The Ongoing War

Appendix 1: Key Players

Appendix 2: Timeline of the Afghan Wars

Appendix 3: Flags of Afghanistan

Copyright

Got Another Hour?

About the Publisher

Introduction

In June 2010 America’s war in Afghanistan surpassed the Vietnam War as the longest war in America’s history. American, British and coalition forces have been fighting in Afghanistan since October 2001, a month following the attacks on the Twin Towers in New York. By the end of the year the war seemed won. But a decade on, the ongoing conflict seems far from over.

Map of Afghanistan

Today’s conflict has historical parallels – in the nineteenth century Great Britain twice invaded Afghanistan, in 1839 and 1878. Both times it had seemingly defeated the Afghan forces only to find that the Afghan soldier, not knowing the meaning of defeat, fought back, inflicting humiliating retreats on the mighty British Empire.

A century later, the Soviet Union, technologically and militarily superior, also discovered to its cost that the Afghan was a tenacious foe, impossible to defeat. After a decade of conflict the Soviet Union withdrew, its military reputation in tatters.

Afghanistan has been in a state of constant conflict for almost four decades. When not fighting external enemies, its people have fought against each other. The civil war of 1989 to 1996, during which the Taliban emerged, was ferocious in its intensity.

The coalition forces of today are embroiled in a seemingly unending war. But why are we still fighting in Afghanistan? What are the lessons of history? Who are the Taliban; who are the Mujahideen, and why was Osama bin Laden so significant?

These, in an hour, are the Afghan Wars.

The First Anglo-Afghan War

In the summer of 1837 the young Victoria ascended the British throne. The Empire was still expanding and at its core gleamed India, the jewel in the crown, the heart of the realm. But to the north-west lay Russia, a rival power with expansionist ambitions. The fear of Russia and Russian influence was a constant factor in Britain’s foreign affairs during the mid-nineteenth century, referred to euphemistically as the ‘Great Game’. When, in 1836, Russia extended her influence into Persia (modern-day Iran), Britain feared for India. Between Persia and India’s north-west frontier lay Afghanistan and it was to this rugged, inhospitable country that Britain turned its attention.

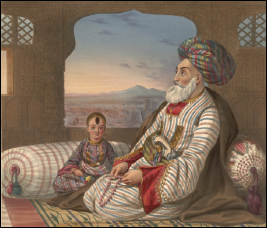

The Amir of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammad Khan (pictured below), had received delegations from both British and Russian dignities. Although the British managed to persuade Dost to decline Russia’s offer of aid, they considered him unreliable and decided that in order to ‘save Afghanistan’ from Russian interference they needed to replace him with someone more compliant to their own needs. The man they had in mind was Shah Shuja, a former king of Afghanistan, who had been deposed in 1809 and remained a figure of loathing throughout the country. But Shuja, now residing at Britain’s expense in India, had the advantage, in Britain’s eyes, of being pro-British.

Dost Mohammad Khan, Amir of Afghanistan, 1826–1839 and 1843–1863

Lord Auckland, Governor-General of India, proposed that the British army escort Shuja back into Afghanistan, oust Dost Mohammad, and place Shuja on the throne where, according to the British, he rightfully belonged. The Afghan nation saw Shuja in a different light but this inconvenient fact was ignored by the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who agreed to Auckland’s proposal, known as the Simla Manifesto. Thus the stage was set for the First Anglo-Afghan War and one of Britain’s greatest military humiliations.

Towards the end of 1838, Britain’s ‘Army of the Indus’ was assembled in Lahore, consisting of almost 10,000 British soldiers and 6,000 soldiers loyal to Shah Shuja (pictured below). The typical British officer of Victoria’s earlier years did not travel light and insisted on bringing with him all the luxuries of the officers’ mess. Thus the troops were accompanied by 38,000 camp followers – cooks, butlers, valets and servants, together with 30,000 camels to carry all the essentials of a military expedition – wine, brandy, cigars, perfume, soap, bed linen and luxurious food. Add to this enough cattle, sheep and goats to feed the expedition for three months, together with the herdsmen to look after the beasts and the butchers to slaughter them.

Shah Shuja, Amir of Afghanistan, 1803–1809 and 1839–1842

By July 1839 this huge, cumbersome train of soldiers and personnel had reached the fortress city of Ghazni in eastern Afghanistan, south-west of Kabul. Along the way the soldiers had seen off numerous gangs of marauding Afghan tribesmen but Ghazni presented the first obstacle on the way to Kabul, capital of Afghanistan. The British stormed the walled city, massacred 500 of its inhabitants and secured fresh provisions. The route to Kabul now lay ahead, within easy reach.

As the convoy approached Kabul, Dost Mohammad fled. The British entered the city unopposed, placed Shah Shuja on the throne and congratulated themselves on a job well done. Having sent most of the army back to India, the remainder settled down to a life of indolence and luxury. They sent for their wives and families and enjoyed cricket, horse racing, music and dancing, while the local Afghans looked on with growing disdain.

Sir William Hay Macnaghten (pictured below) was appointed Minister of Kabul with Sir Alexander Burnes his second-in-command. After a year Macnaghten decided that their situation was secure enough to move out of the capital and set up a settlement, or cantonment, a mile north. It was a decision of staggering foolishness. Surrounded by aggrieved locals, the cantonment was separated from the city by an expanse of orchards, gardens and canals which, in an emergency, would hamper the movement of horses and men; the perimeter was too long to defend and the stores of provisions were situated a quarter of a mile outside the cantonment.

Sir William Hay Macnaghten (1793–1841)

A second British garrison had been stationed at Jalalabad, ninety miles east. In order to secure the route between the cities the British paid the local tribesmen who controlled the dangerous mountain passes for the guarantee of a safe passage. But in an effort to save money, Macnaghten cut the payment by half. Furious, the tribesmen plundered the first caravan to pass through. Macnaghten’s economy drive had, in effect, cut the Kabul garrison off from Jalalabad.

The growing resentment of the local Afghans finally erupted in November 1841 when a mob attacked the British Residency situated within Kabul. Its resident, Sir Alexander Burnes, tried to placate the screaming crowds and, having failed, attempted to make his escape alongside his brother. Both men were soon caught and hacked to death in a frenzied attack.

The newly appointed military commander in Kabul, General William Elphinstone, an elderly and poorly man, crippled with gout, responded by doing nothing. His lack of action merely encouraged the Afghans and while Elphinstone dithered, trying to decide on the best course of action, the Afghans seized the precious store of provisions that lay outside the British cantonment and proceeded to lay siege to the isolated outpost. By December food supplies were so low that the livestock had to be fed on their own dung. With the temperature plummeting and led by a commander unable to command, the situation looked perilous. Elphinstone did finally order a batch of cavalry out to subdue the locals but the mission failed, which only added to the misery within the camp. With food supplies down to the last four days and morale shattered, Elphinstone had no choice but to negotiate.

Elphinstone sent Macnaghten to talk with Akbar Khan, son of the recently deposed Dost Mohammad. Akbar Khan offered the British a safe retreat to Jalalabad but Macnaghten, realizing that Akbar’s authority did not extend over the various different tribes, tried to negotiate with other tribal leaders, playing one off against the other. When Macnaghten’s double-dealing came to Akbar’s attention, he invited the envoy back for further discussions, and there had him murdered. Macnaghten’s head was paraded triumphantly through the streets of Kabul while his body hung from a meat hook in the city’s Great Bazaar.

Akbar ordered the British out, still offering safe passage but demanding in return cash, guns and hostages. The hostages would be returned once his father, Dost Mohammad, was back on the throne. The wounded and sick would also remain behind. Elphinstone had no choice but to accept the offer, knowing that Akbar’s word was meaningless.

Thus, on 6 January 1842, began the retreat from Kabul. Four thousand five hundred British and Indian soldiers together with twelve thousand camp followers faced a treacherous ninety-mile trek to Jalalabad, through mountain passes deep in snow, in freezing conditions, with empty stomachs and inadequate clothing. Full of trepidation, the exodus began.

The sick and wounded left behind were immediately killed while the convoy came under attack as soon as it had left the city (pictured below in The Last Stand of the 44th Regiment at Gundamuck by William Barnes Wollen). A trail of bodies soon lay scattered along the mountain passes, mutilated by local women, leaving a gruesome scene for those trailing behind. After three days, the convoy had only managed ten miles and already three thousand were dead. Many succumbed to the sub-zero temperatures, others committed suicide.

The Last Stand of the 44th Regiment at Gundamuck, 1842 by William Barnes Wollen

On the sixth day, Elphinstone, his second-in-command, and a few women – including one Lady Sale – gave themselves up to the Afghans and were returned to Kabul as hostages. It was Elphinstone’s final humiliation – having failed to command his troops at any point, he had now deserted them.

His men and followers had no option but to plough on, facing one ambush after another, suffering heavy casualties. Surrounded on all sides, the column was pitilessly slaughtered.

On 13 January 1842, the British garrison at Jalalabad spied in the distance one lone horseman coming towards them. The man on the ragged horse, given to him by a sympathetic Afghan farmer, was Dr William Brydon. Later a few Indian sepoys staggered in but Dr Brydon was the only British survivor. The scene was made famous in a painting entitled Remnants of an Army by Lady Butler (pictured below). When asked what had happened to the army, Brydon replied, ‘I am the army.’

Remnants of an Army by Lady Butler

Brydon’s survival and the infamous retreat from Kabul became a gruesome cause célèbre in Victorian Britain and a stark reminder to its politicians that the British army was not the invincible force they believed it to be. On hearing the news, Lord Auckland, the Governor-General of India who had originally proposed the Simla Manifesto, suffered a stroke.

Retribution was swift. A force under the command of Sir George Pollock and Robert Sale, husband of Lady Sale, stormed through Afghanistan, relieved the garrison at Jalalabad and, in September 1842, forced its way into Kabul where Lord and Lady Sale were emotionally reunited. But Pollock was too late to save Shah Shuja, who had been murdered in April 1842, or Elphinstone, who had died, a broken man, in captivity the same month. William Nott, one of Pollock’s second-in-commands, described Elphinstone as ‘the most incompetent soldier who ever became general’.

Pollock, who had been ordered to ‘leave some lasting mark of the just retribution of an outraged nation’, blew up Kabul’s Great Bazaar. Then, having rescued the remaining British hostages, he returned to India.

British prestige had been partially restored and its honour satisfied, but with the restoration of Dost Mohammad to the Afghan throne, the whole farcical and tragic episode had achieved nothing.

Thirty-six years later, in 1878, the Great Game was played again.

The Second Anglo-Afghan War

In 1879, the Amir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali, accepted a Russian presence within Kabul, which alarmed Britain enough to demand their own, to the point that the British army escorted one to the Afghan border. When Sher Ali refused them entry it gave Britain the pretext it needed to mount an invasion.

Advancing in three columns, the British took Jalalabad and Kandahar. The third column, under the command of General Frederick Roberts, took Kabul – by which time Sher Ali had fled. He died soon afterwards, to be succeeded by his son, Yakub Khan.

In May 1879, Yakub Khan and the British signed the Treaty of Gandamak in which, in return for British subsidies, Afghanistan handed over the control of its foreign affairs to Britain and allowed a British envoy to reside in Kabul.

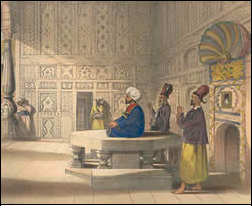

In July, that British envoy, Pierre Louis Cavagnari, arrived, and the Second Anglo-Afghan War was over. Or so the British thought. (Pictured below is Cavagnari, second from left, sitting with the Amir, Yakub Khan, centre.)

Yakub Khan, Amir of Afghanistan, February to October 1879, and Louis Cavagnari (1841–1879)

However, in September, Cavagnari and his fellow Britons were killed. On hearing the news General Roberts, stationed in Simla and preparing to go on holiday, gathered a force and hastened back to Kabul. Yakub Khan rushed out personally to meet him, denying any involvement in Cavagnari’s murder and beseeching Roberts not to attack his capital. Roberts, who found the Amir’s subservience embarrassing, brushed him aside and pushed on.

Once in Kabul, Roberts subdued the locals, rounded up the suspected conspirators, had them executed, and set up fort in a walled part of the city called Sherpur. Remembering the mistakes of the previous war, Roberts built up its defences and fortified it. His precaution was justified as, in December, the local Afghans besieged the fort. The British garrison held out and eventually the Afghans faded away.

Meanwhile, over 300 miles away, outside Kandahar, on 27 July 1880, the British fought a battle against an Afghan force near a village called Maiwand. The British suffered a humiliating defeat (pictured below), with 969 British and Indian soldiers killed and almost 200 wounded. Today some Afghans still raise a toast to the victors of Maiwand. Chased back to Kandahar, the British survivors came under a sustained siege.

Battle of Maiwand: Saving the Guns by Richard Caton Woodville

Roberts, still in Kabul, was ordered to relieve the Kandahar garrison. Thus, setting out on 9 August 1880, with 10,000 soldiers and 8,000 camp followers, and accompanied by almost 10,000 mules, ponies and donkeys, Roberts began the march from Kabul to Kandahar. The convoy covered 334 miles within 22 days, and captured the British imagination, making Roberts a national hero. When the Afghans besieging Kandahar learnt of Roberts’ imminent arrival they turned and fled. Roberts himself fell ill, and much to his chagrin, had to be transported in a doolie (a kind of litter), although as they entered the city on 31 August, Roberts insisted, for the sake of dignity, on riding in on horseback.

A special medal was struck, the Kabul to Kandahar Star (pictured), known informally as the Roberts Star, celebrating Roberts’ achievement.

Kabul to Kandahar Star

Roberts then defeated Yakub Khan in the Battle of Kandahar on 1 September 1880, and having settled the more compliant Abdur Rahman, grandson of Dost Mohammad, on the Afghan throne, proceeded to pull out of Afghanistan. Abdur Rahman would remain in power until his death in 1901, while the treaty signed at Gandamak remained in place for forty years. But ultimately, in a repeat of the First Anglo-Afghan War a generation earlier, Britain had won a war but achieved very little.

The Third Anglo-Afghan War

A third Anglo-Afghan War erupted in 1919. Afghanistan had remained neutral during the First World War but Amanullah Khan’s position as ruler was threatened by civil unrest. As a means of diverting attention from internal dissension and believing the British too exhausted after the exertions of war to resist, Amanullah announced his intention to free his country from the Treaty of Gandamak and invade British India.

On 2 May 1919 Afghan forces crossed the border into India and occupied the strategically important town of Bagh as a prelude to further attack. But within a week British and Indian troops had forced the invaders out. The British pushed on into Afghanistan and fought a number of skirmishes along the way. The use of the RAF proved decisive and bombs dropped on the presidential palace in Kabul devastated Afghan morale and Amanullah’s will to resist.

An armistice signed on 8 August 1919 resulted in the Treaty of Rawalpindi in which Britain agreed to annul the Treaty of Gandamak and play no further role in shaping Afghanistan’s foreign policy. Although Afghanistan had never been part of the British Empire, it now saw itself as entirely free of Britain’s interference, and, to celebrate, 19 August was declared Afghan Independence Day, an occasion still celebrated today.

The ‘Saur’ Revolution

As king, Mohammad Zahir Shah (pictured below) ruled Afghanistan for forty years, coming to the throne as a 19-year-old in 1933. But in July 1973, while in Italy undergoing eye surgery, his cousin and former prime minister Mohammad Daoud Khan, whom Zahir had sacked in 1963, staged a coup, abolished the Afghan monarchy and established a republican government with himself as its first president.

Zahir Shah, king of Afghanistan, 1933–1973

Daoud set about implementing reform – the emancipation of women and the suppression of Islamic fundamentalism. The Islamists migrated across the border into Pakistan, where the Pakistani secret service trained them to fight. Among them were two men who were to play a large role in the Afghan civil war twenty years later: Ahmad Shah Massoud and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Both were members of the Mujahideen. Massoud exploited the discontent caused by Daoud’s reforms and staged an uprising. It failed and Daoud used the attempted coup as a pretext for enforcing greater repression of Islamic fundamentalists. Massoud and Hekmatyar fell out and although nominally fighting for the same cause became and were to remain bitter enemies.

Daoud had been accepting shipments of arms from the Soviet Union but following a falling out with the Afghan communist party – the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) – he expelled the Soviet advisers sent by Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, and looked elsewhere for assistance.

The Soviet Union feared that Afghanistan was about to ally itself to the West. The final, irrevocable split with the Soviet Union came in April 1977 during Daoud’s state visit to Moscow. When Brezhnev objected to the encroachment of American and NATO influence within Afghanistan, Daoud reacted angrily, ‘We will never allow you to dictate to us how to run our country and who we employ in Afghanistan . . . Afghanistan will remain poor if necessary but free in its acts and decisions.’ As he left he had to be reminded to shake Brezhnev’s hand. A year later Daoud would regret his show of defiance.

In April 1978 a prominent PDPA member was assassinated and his subsequent funeral attracted and stirred the emotions of large numbers of Afghan communists. Daoud, sensing the danger, attempted a crackdown but not with sufficient vigour, for on 27 April, the PDPA, trained by the Soviet Union, staged a coup, the Saur (or April) Revolution.

Daoud, along with members of his family, was shot in the presidential palace. Brezhnev had no input into the coup but equally, still smarting from Daoud’s defiance, took no action to prevent it.

Daoud’s death was not publicly announced and the new president, the pro-Soviet Nur Mohammad Taraki, announced that former president Daoud had ‘resigned for health reasons’. Taraki renamed Afghanistan the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan and introduced a red Afghani flag not dissimilar to the hammer and sickle flag of the Soviet Union. The body of Daoud was found thirty years later, in 2008, and in March 2009 Daoud was reburied with full state honours.

The Communist Era

Taraki immediately set in motion a programme of Marxist reform – land reforms, the banning of forced marriages, discouraging women from wearing the veil, promoting literacy and, most controversially, the advancement of women. Their aim was to eliminate the ‘backwardness of past centuries within the lifespan of one generation’. But for factions within the government, this was too much too soon. The pace of reform became an issue and splits emerged, notably between Taraki and his prime minister, Hafizullah Amin.

Any reform was too much for the conservative Afghans – the redistribution of land cut through traditional boundaries and ignored local needs, and the liberation of women was a complete anathema to the Islamic Afghans for whom the woman’s place was very much at home.