Полная версия

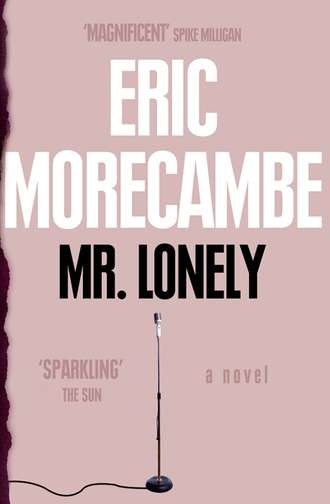

Mr Lonely

Sid had, by this time, seen all the pictures on the walls and read all the ‘Thank you, Leslie’s on them. One day, he thought, my picture will be in here and I’ll just put, ‘What’s the time, Sid?’

‘What’s the weather like in Hollywood?’ Leslie asked Shirl. ‘What do you mean, you don’t know?’ He looked at the clock and then at Sid. ‘Oh, you’re in New York.’

Sid moved over to the window and looked out on a busy London street.

Leslie continued his transatlantic conversation. ‘Yeh, at the Savoy. A suite. What? But what’s wrong with the Savoy? All right, darling,’ he smoothed. ‘Sure. I’ll see to it. The Oliver Mussel. Yeh, Messel.’ ‘Messel, Shmessels,’ he whispered to himself. ‘At the Dorchester. Okay, kid. Yeh. And to you. Goodbye. Sure. I’ll give Rhoda your love.’

Leslie put the phone down in a small state of shock. He then picked up the other phone and dialled one number. After two seconds he said, ‘Stella, get the Oliver Messel suite for Shirl. I know you’ve booked her in at the Savoy. So get her out and in to the Oliver Messel suite at the Dorchester. Look, I don’t give a Donald Duck how you do it. Do it.’ He slammed the phone down.

Sid was now standing at the edge of the desk with the clock facing away from him. Leslie turned it back so Sid could see it very clearly. Sid took the hint and carried on with, ‘So I thought it was time I had a rise.’

‘I’ll have a word,’ Leslie almost growled.

He then put his hand out to be shaken and left Sid to find his own way out. Sid looked at his watch. Seven minutes in all he had been with his agent to talk over his future and that included a five-minute phone call from New York. Christ, Sid thought, that’s what I call looking after your artist. He saw Lennie still waiting. ‘A word in your ear, son,’ he said. ‘If and when you get in, speak quickly.’

Lennie did not know what he meant, but he would.

Sid walked out of the office entrance into a windy Piccadilly. It was still early. There was no rush to get home and he need not be at the club until about eightish. He looked at his Snoopy watch and thought he saw Leslie Garland’s face ticking from side to side. It was only three-thirty. He put his head down to face the wind, pulled his overcoat more closely around himself and, at a fair pace, walked down Piccadilly into the Circus, along Shaftes-bury Avenue, and then across into Soho itself. He slowly lifted his head out of the top of his overcoat and looked at some of the pictures outside small clubs, cinemas, sex shops and bookshops with magazines that made Health and Efficiency look like something the verger handed out with Hymns Ancient and Modern.

Unbeknown to Carrie, Sid had won a hundred and odd quid at the club on a Yankee bet. At this moment it was burning a hole in his pocket. He stopped to look at a small ad frame. Sid looked at one particular card in the small frame. He read it twice. He had to. He could not believe it. It read:

Miss Aye Sho Yu—Oriental Massage—Number 69. Three flights. Two masseuses. No waiting. Your joy is our pleasure. Please knock.

Sid looked around just to make sure nobody was actually looking at him, eyeball to eyeball, before he entered. He had one more look at the frame. Should it be, he thought, Aye Sho Yu, or the other next to it: Turkish Delight—‘not like that—like that. You get the massage’—written on a fez? No, thought Sid, Aye Sho Yu.

As he started his walk up three flights of stairs, he thought, Of course—the reason I’m doing this is in case I get a good idea for some gags or a sketch for the club, or maybe even TV. He knew that what he had just said to himself was a complete excuse and really about the weakest he could have thought of. No way would he be able to use one line, one thought or one iota of an idea in his professional work. I’ll turn back. I’ll leave. Why? Because I am right. It’s wrong. But suppose somebody actually saw you coming into the building. So? So. I’ll tell you so. If you leave now and he’s still there outside, he’s going to look at you and say to himself, ‘Good God. He didn’t last long’, isn’t he? That’s true. Yes, it is, isn’t it? Yes. Then keep going. Okay.

He had one flight to go, past a man coming down the stairs. Sid stopped and looked towards the wall as the man passed him and then turned his head to watch the man as he staggered down the stairs. Sid thought, he’s either drunk or exhausted.

On the landing of the third flight were four doors, numbered 68, 70 and 71. Where was 69? Oh—there. 69 was printed on its side. Clever. Sid took a deep breath and knocked on the door, softly, so softly in fact that had there been woodworm in the door they would not have heard him. Door 70 opened and a man’s face furtively looked out. Sid turned, but only just in time to see the door close quickly. From the fourth floor a fat man appeared. He continued his way downstairs. He was about eighteen stone. If he had forgotten anything on the fourth floor it would have to remain there as it would have killed him to go back up those stairs. Sid knocked harder. Number 69 opened and he came face to face with a pretty Chinese girl.

‘Yes?’ she asked.

‘I … er … saw your … er … advert in the frame downstairs.’

‘Massage?’

‘Er … please … yes.’

‘Would you please enter. I will ask Miss Yu if she can help you.’ She put both hands together and bowed her head. ‘Please to wait.’ She pointed to a small couch. ‘Please to sit.’

Sid sat. The wall at the back of the couch was decorated with a red dragon that looked as if it had been painted by the PG Tips monkeys. The girl was dressed in a long black nightgown as far as Sid could tell. She left the tiny hall and, after one knock on a door, went through into another room. On the back of her nightgown was embroidered a golden dragon. Instead of fire there was a number 69.

Sid looked round the tiny hall. On the door that Miss Takeaway had gone through was a full-sized poster of Bruce Lee kicking the Eartha Kitt out of about thirty Chinamen, all armed with guns, knives and hatchets. Bruce had only his bare hands and his bare feet. He suddenly disappeared as the door opened and in his place stood Miss Takeaway.

‘Miss Yu will see you please.’

Sid stood up and hit his head on the swinging paper lantern. He walked past Bruce Lee and Miss Takeaway into a room with a bed in the middle of it that was very reminiscent of an operating table. It was covered with a white towel. Everything looked clean and the air was pleasantly perfumed. The square room was completely painted in willow-pattern style and looked like some of the plates his grandma used to have.

Sid thought, If I stripped off and lay on that table, I’d look like a chip.

A door opened and in came Miss Yu. She also had the look of an Oriental and was wearing a long dress that was split down one side from the floor to just under her left arm. She looked an old twenty-six, about thirty-two, but she looked good. Well—good enough, when money’s burning a hole in your pocket.

‘You would likee massage?’ she asked in the phoniest accent he had ever heard.

‘Well, yes. You know—just to get rid of a few aches and pains.’

‘You wantee normal or special massage?’

‘What’s the difference?’

‘A tenner,’ she replied in perfect English.

‘How much is a normal massage?’

‘A tenner.’

‘And what would I get for a normal massage?’

‘The same as a special massage only quicker.’

‘American Express?’

‘Balls!’

‘Okay then.’

‘I take it honourable gentleman would likee special?’

Sid expected Edward G. Robinson to walk in at any moment and the whole thing to develop into a Tong war.

‘I will leave you to get undressed,’ she went on. ‘If you would let me have the twenty qui … pounds, I will not embarrass you by remaining. Of course, if honourable gentleman pays twenty-five pounds, my beautiful younger, virgin sister helps me to makee you relax more in longer time.’

‘Twenty-five?’

‘Only if you wishee complete relaxation, but if master only desire … er … quickee … er … I alone am willing to accommodate.’

Sid said to himself, That fella going downstairs wasn’t drunk or exhausted. At twenty-five quid he was probably broke. However, after the win he had the cash to spare and the urge to spend it. ‘What’s your sister’s name?’ he asked.

‘Why.’

‘Well, I think for twenty-five quid I’d just like to …’

‘Her name is Why.’

‘Why?’

‘Yes, Why.’

‘Not Why Aye Sho Yu?’

‘All is arranged.’ She crossed herself. Sid looked slightly surprised at a Chinese Roman Catholic, but in Soho …?

‘Were you recommended?’ she asked demurely.

‘No, no, no. I would put myself down as a one-off.’

Miss Yu waddled over to a small gong on a pair of wedges. If she had any wish to commit suicide, she could have jumped off them. She hit the gong with an object that a book like Family Planning or Getting Married would have called a phallic symbol. What Miss Yu called it she kept to herself.

‘Please undress and lie on table,’ she said. She started to walk away from him, then turned round to add, ‘Face upwards.’ She smiled.

‘I thought Chinese people didn’t laugh.’

‘It all depends on who they are with, oh great one!’

She threw Sid what Carrie would have called a face flannel, with which to save himself any embarrassment. She then left the room, walking through a river in the willow pattern. Sid began to undress. Through a loud speaker, which was painted so as to blend in with the willow pattern, and rested on a Chinaman’s head, came a noise that made Sid almost jump out of his pants. It was very loud and sounded like what a Cockney would call in rhyming slang ‘a jam tart’. Then, as it settled down and the sound was lowered, it became some sort of Oriental music, although quite modern, it was to Sid’s mind Japanese. A Japanese group was singing songs like ‘The girl from Okayama’ and ‘Oh Yokahama, where the wind comes sweeping down the plain’.

Sid was now in his Y-fronts. The small towel Miss Yu had given him was laughable. He hoped there was a shower for later and also a bigger towel with which to dry himself. He kept on his Y-fronts and also his socks, as, although the white carpet looked clean, he was more than a tiny bit afraid of verrucas. He sat on the edge of the white, towelled mattress and swung his legs. It might make a good sketch, he mused. Lies, all lies, Sidney, and you know it. That’s true, he murmured back to himself. How about Carrie, you rotten sod? Have you no conscience? He smiled. Ah, he answered, conscience doesn’t stop you from doing it. It just stops you from enjoying it. He started to swing his legs from side to side. Does that mean to say if you don’t do it you’ll enjoy it? he asked himself. He was now on his back, cycling his legs in the air. That doesn’t make sense, he replied. He leaned forward to touch his toes. You see, he continued. He pulled his feet towards him like a footballer with cramp. What? He grimaced for the trainer to be sent on. Exactly.

A gong sounded and through the river of the willow pattern entered Why. She carried a tray on which were oils and perfumes. The thing that puzzled Sid was that earlier on she had left him via Bruce Lee and had now come back via the river. Did that mean that rooms 68, 70 and 71 had connecting doors? Had she gone through room 70 to get to 69? His mind went back to reading the advert outside. Next to him, he remembered, had stood the biggest negro he had ever seen in his life, big enough to make Mandingo look like a black Ronnie Corbett. He remembered also seeing another ad: ‘Madame La Rochelle, MBE. French taught the easy way. Guaranteed satisfaction. Room 70—third floor.’

Sid looked at Why. She did not look overworked. He noticed as she put down the tray that she had changed her dress. She was now wearing very little everywhere. She did not speak and, as she walked away from him, he looked at her lovely little firm, round bum and thought, I’ll never eat another hot cross bun again.

The gong sounded. Sid looked towards the river but nothing happened because Aye came through another door which was painted as a rice planter. As the door opened Sid thought he saw a pained expression on the face of the painted rice planter as the whole of his arse was moved from the rest of his body.

Aye was carrying a folder. Her outfit—well, with Why you could see through what she was wearing, and with Aye you could not see what she was wearing. To Sid twenty-five pounds was a lot of bunce, but at least they were working for it. Judith Chalmers would have difficulty in describing Aye’s costume—two pieces of elastoplast and a cork.

‘Why you no undressed?’ Aye asked Why.

‘Well, you see …’ Sid started to answer.

‘I was asking my sister, Why. Why you no undressed?’

‘Oh.’

Any moment Sid expected Aye to say, ‘Did white man arrive in big iron bird?’

‘Why? Please.’

Why went to the leg end of the high mattress, while Aye went to the other end, placed her hands on Sid’s shoulders and easily and professionally forced him down. Why grabbed his underpants and, with one deft movement, whipped them off, and his socks too, with such speed and dexterity that would have made a hospital nightnurse applaud and many a magician go home and practise. Sid’s first reaction was to reach for the towel, but that was by now in the same place as his underpants and socks, wherever they were. So, as he first thought, he felt like a chip.

Aye handed him the contents of the folder. ‘Please to take plenty good look at Chinese art,’ she said.

God, she was a bloody awful actress. Sid was given six ten-by-twelve blow-ups of what were once known as French postcards—the kind of thing all men looked at but would not have on their person in case they ever got knocked down or run over.

‘Are you showing me these for a reason?’ he asked.

‘To help patient relax,’ Aye answered.

‘Well, that’s the last thing they’re going to do.’

Why started to massage Sid’s big toes very gently, while Aye held his head up so he could see the Chinese French postcards without having to lift his arms in the air. The pictures were of hands and things. Sid recognized Why by the ring on her finger. After looking at the pictures twice through, Aye took them from him and let his head fall back hard on the table, which made his Adam’s apple bounce up and down fast enough to make cider. Why was now massaging the back of his knees. Aye put the pictures back in the folder and put them on the tray. She then picked up a tin of Johnson’s baby powder and powdered him with it, as if it was a salt-cellar and he was a chip. Aye and Why were now standing either side of his shoulders. The lights started to dim on their own. Sid wondered, Am I being watched? Am I part of room 70′s French lesson? He tried to look round for an eye hole but, from his position, could not see one. Powder and hands were everywhere. At one stage he thought he felt five hands, but he dismissed that thought.

‘Please—you have name?’ Aye smiled.

‘Er … Dick.’

‘Dick. Very nice name.’ Why said shyly, ‘You have number two name?’

‘Barton.’

‘Dick Barton. Velly nicee name,’ Aye said, with a resounding slap.

This woman must be the worst actress in the world, Sid thought. The nearest she’d ever been to the East was Ley Ons, the Chinese Restaurant in Wardour Street, and, as far as 69 was concerned, that was the special fried rice on the menu.

Powder was now settling. Another hard slap.

‘Please vill you turn ofer.’

That was the third accent she’d used. Sid did as she commanded just in case she said, ‘Ve have vays of making you turn ofer.’ Forget Edward G. Robinson, Sid thought, as Why tried to walk up and down his spine. But keep an eye out for Curt Jürgens rushing in to tell us all that the Allies have invaded France and the Führer is insane.

‘Over again, please.’

Sid turned, but a little too quickly, before Why could get off the table. She landed on the floor flat on her hot cross bun. Why came out with some language that Sid had only heard once before, when a red-hot rivet had landed on the inside of a ship-builder’s leather apron.

‘Sorry,’ Sid said and got up to try to help Why off the floor. As he did this the lights started to get dimmer. The room was now almost dark, obviously from some timing device. Why put out her hand to grab what was, she thought, Sid’s helping hand, but Sid’s helping hands were under both of her arms. Sid let out a scream that would have sent both Edward G. Robinson and Curt Jürgens running out of the room.

By this time Aye was making her way round to both of them, when, on cue, the room went into complete darkness. Aye tripped over Why’s legs and fell with arms outstretched. Nature being what it is, self-preservation took over, and she held on to the first thing she grabbed. Sid let out yet another scream.

The music got louder and faster. There was a knock on the rice planter and a female voice shouted, ‘Are you all right, Doreen? Doreen, Stella, are you all right?’

‘Switch the bleeding light on,’ Doreen or Stella shouted.

The lights slowly came up. The rice planter was once more in his painful broken position and Sid saw what he took to be Madame La Rochelle standing in the doorway with the eleven-foot negro, both naked.

‘Shut that door,’ one of the girls shouted.

What a great catch phrase, Sid thought. I must remember that.

Madame La Rochelle shut that door. The rice planter must have been in agony. Sid, Doreen and Stella were still on the floor.

Sid laughed painfully. ‘Well, at least it’s been different. Original, even. Stella?’

‘Yes?’

‘How do you feel?’

‘All right.’

‘Probably more shock than anything,’ Sid grinned. He stood up. ‘Well, Doreen,’ he asked. ‘Do I get a refund, or do we do a deal?’

‘Refund?’ She said the word as if she had just heard it for the first time, as in ‘Me Tarzan—You Refund’.

‘Well, it was you who had the thrills. Both of you grabbed me by the orchestras.’

‘Orchestras?’ they chorused.

‘Yes. Orchestra stalls. Now do I get a refund? Let’s say half, or do I tell the police you both tried to rape me?’

All three were standing up. Stella, Doreen and Sid.

‘No refund,’ said Doreen.

‘Okay then,’ Sid mused, ‘we carry on where we left off.’

All three smiled. Doreen nodded, Stella rubbed her bruises and Sid said, ‘Lights, music, action. Doreen?’

‘Yes.’

‘Don’t keep doing that. It doesn’t help,’ Sid said in the darkness.

CHAPTER THREE

April, 1976

Sid’s way of earning a living was, to say the least, hard. The idea of his job was to entertain the people, who had paid sometimes £3.50, sometimes £15 per person, for what was loosely called dinner. Dancing was thrown in, rowdies were thrown out and, now and again, dinner was thrown up. Gambling, if permitted, was always kept well away from the entertainment because the management did not like the audience to hear the cheers of a man who had just won seventy quid, or the screams of a man who had just lost seven hundred quid, although they were less against the cheers than the screams. If the star name was big, so was the business; if the star name was not big, neither was the business. Service was normally slow but what’s the rush anyway. The waiters were mainly foreign, the waitresses were usually British and the customer was often hungry. Invariably the room was dark; only the staff could see their way around because God has given all nightclub waiters special eyes. The toilets were sometimes as far away, or so it felt, as the next town. The sound system was the nearest thing to all the bombs falling on London during the last war condensed into two and a half hours approximately.

Sid’s job was to come out on to a small platform or stage and try to tell you how much, thanks to him, you were going to enjoy yourselves. The nightclub audience is not prudish but it will not laugh at a dirty joke unless it is filthy. So the comic feels that he has to gear his material to that audience for safety, the safety of his job. No one is going to pay a comic good money if the laughs are not there, so laughs have got to be found and the safest way is the oldest way—give them what they want. That maxim still applies, from the shows at Las Vegas to opera at Covent Garden. If they do not like it, they don’t come. In this side of show business it’s called ‘arses on seats’. If the seats are empty, so is the till. So Sid had to walk out and face a basically uninterested audience and get laughs with the first of his four or five 12- to 15-minute spots, and, of course, have something prepared in case the lights failed, the star got drunk or the resident singer had not turned up because she had had a row with the fella she was living with and her husband had ever so slightly changed her face around a little when she went back to him. Not a lot, she’ll be fine when the swelling goes down!

Sid was on the side, waiting to go out there for the first of his spots. The group were on their last number, which received its usual desultory applause. Sid’s music started—‘Put on a happy face’. He checked his flies and walked out as if he was the biggest star in the world. Wearing a wellcut, modern evening dress suit, mohair of course, and a pale blue frilly dress shirt that d’Artagnan would have been proud to wear, he timed his walk to the mike so that he could take it out of its socket, put it up to his mouth and sing the last line of the song ‘S.. o.. o.. o.. o put on a happy f.. a.. a.. a.. c.. c.. e. Thankyouladiesandgennelmengoodevening.’ The end of the song and the welcoming words corresponded volume-wise with the air raid on Coventry. Three quick blows into the mike to check that the sound was working. ‘Now first of all, ladiesandgennelmen, can you hear okay?’

‘No,’ shouted a voice from the blackness.

‘Then how did you know what I’ve just said?’ He tapped four more times on the mike top with his fingers. ‘My name is Sid Lewis, ladiesandgennelmen. The most important thing is—are you enjoying yourselves?’

‘No,’ was the shout from the same voice from the same blackness.

Sid put his hand up to his forehead and looked into the distance, reminiscent of Errol Flynn as Robin Hood saying to Alan Hale as Little John, ‘Run, it’s the Sheriff of Nottingham.’ What he did say was, ‘Don’t worry about him, folks. He’s only talking to prove he’s alive.’ He put his hand down. ‘I’ll tell you something about him. He’s a great impressionist—drinks like a fish. His barber charges him 80p—20p a corner!’

He had no worries about the voice coming back at him again from the darkness because the voice was a plant, a stooge. By the time Sid had done his barber joke, the stooge was backstage drinking a pint, paid for by Sid.

Sid was now into his act, walking about with the mike. ‘Let me tell you something else. No, listen. A father and son. Got that? A father and son walking in the country. Now, listen. A father and a son. It’s all good stuff this. When suddenly a bee lands on a flower. The little boy kills it with a rock. No, listen, you’re laughing in the wrong place. His father says, “For being so cruel you won’t have any honey for a year.” Walking a bit further, the boy sees a butterfly land on a flower. He cups his hand around it and squashes it. No. Not yet. Don’t laugh too early. Soon. I promise you. S.. o.. o.. o.. o.. n. The boy’s father says, “For doing that you won’t get any butter for a year.” Then they went home. His mother was in the kitchen making dinner, when she saw a cockroach. She stamped on it and killed it. The little boy said, “Are you going to tell her, Dad, or am I?” … Cockroach … Do you get it? Cockroach. C-o-c-k … Oh, well, it’s up to you.’

Sid kept moving around the small stage, looking at nearby tables. ‘Here’s one. The same little boy. That’s right. The same little boy ran towards his mum wearing a pirate outfit. His mum says, “What a handsome-looking pirate. Where’s your buccaneers?” The little boy says, “Under my buccanhat.” Now, listen. Here’s another one you might not like. You’ve got to listen to me, lady. I work fast. The same boy, same boy. He’s on a picnic with his mummy and daddy and he wanders off. No, not for that, lady! Just for a walk and he gets lost … Aw … Aw … Come on, everybody. Aw … Sod you, then. Anyway, this little boy’s lost, same little boy, so he drops to his knees to pray. “Dear God, help me to get out of here.” A nice prayer. Straight to the point. Now then, as he’s praying, a big black crow flies overhead and drops his calling card right in the middle of the little boy’s outstretched hand. The little boy looks at it and says, “Please God, don’t hand me that stuff. I really am lost …” Now, listen … Here’s one. You’ll like this one, lady. I can see you have a sense of humour. I can tell by the fella you’re with. Now, listen. This one’s for you.’