Полная версия

Dickens: History in an Hour

DICKENS

History in an Hour

Kaye Jones

About History in an Hour

History in an Hour is a series of ebooks to help the reader learn the basic facts of a given subject area. Everything you need to know is presented in a straightforward narrative and in chronological order. No embedded links to divert your attention, nor a daunting book of 600 pages with a 35-page introduction. Just straight in, to the point, sixty minutes, done. Then, having absorbed the basics, you may feel inspired to explore further.

Give yourself sixty minutes and see what you can learn . . .

To find out more visit http://historyinanhour.com or follow us on twitter: http://twitter.com/historyinanhour

Contents

Cover

Title Page

About History in an Hour

Introduction

The Early Years

London

Miss Maria Beadnell

The Creation of ‘Boz’

The Early Novels

The 1840s

Dickens in America

Dickens in Europe

Dickens the Philanthropist

Return to Journalism

Dickens the Reformer

Dickens’ Private Life

Dickens the Public Reader

The Later Years

Appendix 1: Key Figures

Appendix 2: Timeline of Dickens

Copyright

Got Another Hour?

About the Publisher

Introduction

One of the most celebrated British authors of all time, Charles John Huffam Dickens was born on 7 February 1812 in Portsmouth England. Though Dickens received little formal education, he produced some of the most famous works of the Victorian era, such as Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol, novels that continue to be enjoyed today. Dickens did not limit himself to being a novelist, he was also a journalist, social commentator, philanthropist, husband, lover and father.

Charles Dickens c. 1867, photograph by Jeremiah Gurney

As a celebration of the bicentenary of his birth in 2012, this ebook will guide readers through the formative events, relationships and experiences that inspired and underpinned his work.

The Early Years

Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth on 7 February 1812. He was the second child of Elizabeth Dickens (née Barrow) and John Dickens, a clerk in the naval pay office attached to the nearby dockyard. Due to the nature of John’s work, the family moved frequently during Dickens’ earliest years, with stays in and around London, and to Sheerness, before a more permanent posting to the Chatham Dockyard in Kent in 1817. Here, the family lived at 2 Ordnance Terrace, a six-roomed house with two live-in servants.

Ordnance Terrace, Chatham, photograph by Clem Rutter

It was Elizabeth Dickens who took responsibility for the education of Dickens and his elder sister, Fanny, in these early years. Alongside her lessons in English and Latin, Dickens became an avid reader. He spent many hours in the attic enjoying the books from his father’s collection, such as Don Quixote, The Arabian Nights and Robinson Crusoe. Dickens also received some schooling at a nearby dame school. Prior to the introduction of compulsory education for children in 1870, these schools provided a much-needed service for families who were too poor to pay for private schooling. Dame schools, often run by an unqualified woman from her own home, helped many children master the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic.

In 1821 Dickens left the humble dame school and enrolled at the Reverend William Giles’ School, a private, fee-paying establishment. It was around the same time that John Dickens’ financial problems, of which the origin is unknown, caused the family to relocate to a smaller house in Chatham. Money troubles, however, did not stand in the way of a happy childhood. At school, Dickens made great progress, while at home he wiled away his time with make-believe games, performing recitals and plays with his sister, Fanny. On several occasions the pair saw plays by Shakespeare at the Rochester Playhouse, inciting in the young boy a love of the theatre that would endure throughout his life. With its majestic cathedral, ruined castle and bustling river, the city of Rochester also captured his imagination.

Somerset House, c. 1836

The next year, however, John Dickens took up a new position at Somerset House in Central London. Dickens remained in Chatham to finish the term at Giles’ School and then joined the family at 16 Bayham Street. Situated in the less genteel suburb of Camden Town, Dickens described it as having a ‘basement, two ground floor rooms, two on the first floor, a garret and an outside wash-house.’ When describing the Cratchit family home in A Christmas Carol, it was to Bayham Street that Dickens looked for inspiration. Home to his parents, four siblings, his relative through marriage, James Lamert, and an orphan brought from the Chatham Workhouse, the house must have felt extremely cramped and considerably less comfortable than any previous family home. Reflecting on this time in his life, he told his friend and biographer, John Forster, of his distress at losing his life in Chatham and his overwhelming desire to be ‘taught something, anywhere.’ To make matters worse, Fanny was about to enrol on a four-year course at the Royal Academy of Music – at considerable expense to the family.

London

By the time the Dickens family arrived in London in 1822, it was the largest city in the world and the heart of the British Empire. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, industrialization had been transformed the social and economic character of the city. From shipbuilding to domestic service, London thrived as a centre of production and employment. Workers from as far afield as India and China flocked to the city in search of new opportunities, causing a dramatic and continual increase in the city’s population.

Not all of London’s inhabitants, however, shared in its wealth and prosperity. High levels of poverty, caused by unemployment and low wages, created scores of slum neighbourhoods that came to represent the darker side of this great city. For the young Dickens, these poor areas – and their inhabitants – replaced Chatham as the focus of his attention. He looked upon slums like the Seven Dials, situated close to his Camden home, with equal amounts of fascination and repulsion and would find inspiration from their squalor and vice throughout his literary career.

On 26 December 1823, the family left Bayham Street and moved to 4 Gower Street North, a small house in the suburb of Bloomsbury. With his father’s debts increasing, his mother, Elizabeth, attempted to alleviate the financial burden by setting up a school for young ladies (pictured below). Known as ‘Mrs Dickens’ Establishment’, the venture was a complete failure, despite Dickens’ attempts to drum up business in the local area. As he would later recall, ‘nobody ever came to the school, nor do I recollect that anybody ever proposed to come, or that the least preparation was made to receive anybody.’

Elizabeth Dickens

The next attempt to ease the family’s financial burden came in the form of a job offer from James Lamert, the family’s former lodger. Employed as the manager of a local boot-blacking factory, he suggested that Dickens get a job at the factory and do his bit to support the family. While Dickens staunchly protested, his parents gratefully accepted the offer.

On 9 February 1824, only two days after his twelfth birthday, Dickens left his home in Gower Street North and walked the three miles to Warren’s Blacking Factory at 30 Hungerford Stairs, the Strand. His job was to label the individual pots of blacking, a mixture used for polishing boots. In return, he received six shillings per week, approximately £12.58 in modern currency. In this ‘dirty and decayed’ environment, as he would later describe it, Dickens quickly became known as ‘the young gentlemen’ among his fellow workers. While some may have treated him as an outcast, a young boy called Bob Fagin took Dickens under his wing. He would later become the namesake for one his most famous villains, Fagin, in Oliver Twist.

Debtors’ Prison

Within two weeks, any hope of escaping the rats and the monotony of the Blacking Factory was quickly crushed when his father was arrested for debt. On 20 February 1824, John Dickens was detained in a local sponging house, a place of temporary confinement for debtors. His crime was the non-payment of a debt worth £40 and 10 shillings to John Kerr, a local baker. As his father was detained on a Friday, Dickens spent the weekend running messages across the city, desperately trying to raise the £40 that would secure his release and prevent any further legal action.

[no image in epub file]

The Courtyard of Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison

But Dickens’ efforts were in vain. On Monday 23 February 1824, he accompanied his father to the Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison. Situated on the south bank of the River Thames, Dickens later described the prison in his novel, Little Dorrit. It was ‘an oblong pile of barrack building, partitioned into squalid houses standing back to back, so that there were no back rooms; environed by a narrow paved yard, hemmed in by high walls duly spiked at the top.’ Humiliated and broken, John Dickens urged his son to never make the same mistakes that he had: ‘if a man had twenty pounds a year and spent nineteen pounds, nineteen shillings and sixpence, he would be happy; but a shilling spent more would make him wretched.’

With his father imprisoned and unable to support the family, Dickens’ meagre salary from the Blacking Factory was needed more than ever. By the end of March, the family had left the house at 4 Gower Street and had moved into John’s cramped room in the Marshalsea. Dickens did not accompany the family and was instead sent to lodge with Mrs Ellen Roylance in Little College Street, Camden Town. His six shillings covered the cost of food and board and he visited his family on Sundays.

The enforced separation from his family, made worse by the considerable distance between Camden and Marshalsea, quickly became too much to bear. After emotionally breaking down on one of his Sunday visits, alternative accommodation was found in nearby Lant Street, allowing Dickens to take breakfast and supper with his family every day.

On 28 May 1824, John Dickens declared himself an insolvent debtor and agreed to settle all his debts at a later date. In return, Marshalsea granted his freedom. One week later, John inherited £450 from his late mother and used this money to clear some of his debts, now totalling around £700. The reunited family moved to 29 Johnson Street, Somers Town. John set out on a new career path, becoming a journalist for the British Press in 1825, having retired from the Navy on an annual pension of £146.

A decision was now taken to remove Dickens from Warren’s Blacking Factory and enrol him at the Wellington House Academy on Hampstead Road. Elizabeth resented this decision, arguing that her son should continue working to support the family. In a later reflection on this episode, Dickens wrote ‘I know how all these things have worked together to make me what I am: but I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back.’

Artist’s Impression of Charles Dickens at the Blacking Factory

The emotional impact of his time at Warren’s Blacking Factory and his father’s imprisonment at Marshalsea should not be underestimated. While the family never spoke of it again, the sense of being ‘utterly neglected, hopeless’ and ashamed, as he would later recollect, haunted Dickens for the rest of his life. Moreover, only two people – his wife, Catherine, and friend, John Forster – would ever learn about these events during his lifetime. Looking to his novels, the repeated themes of unhappy or orphaned children, deserting parents, money troubles and imprisonment, suggest that Dickens never fully came to terms with these experiences and, more importantly, the parents, especially his mother, that caused them.

The Young Dickens at Work

In March 1827, after studying for almost two years at the Wellington House Academy, his father’s employer, the British Press, went bust. Evicted for non-payment, the family moved house again, and Dickens and Fanny were taken out of school. Once again it was decided that Dickens should get a job and help to support the family. He was employed as a solicitor’s clerk, firstly for Ellis and Blackmore of Gray’s Inn and then for Dickens Molloy of Symond’s Inn. Reminiscent of Warren’s, his employment at Gray’s Inn was secured by his mother through a junior partner, Edward Blackmore, who boarded at her aunt’s house at 16 Berners Street. He found the environment unappealing and developed a general dislike towards solicitors, later weaving them into many of his novels, particularly Bleak House. To counteract the tedium of the office, Dickens analysed and imitated the clerks and street vendors he met while running errands. According to his colleague, George Lear, Dickens developed a strong, local knowledge of the city and seemed to know about everything from ‘Bow to Brentford’. In the evenings, Dickens frequented, and sometimes performed in, the local theatres and music halls, generally with his friend and fellow clerk at Ellis and Blackmore’s, Thomas Potter.

As he didn’t intend on remaining a solicitor’s clerk for long, Dickens investigated other career options. Journalism was of particular interest and he began teaching himself shorthand. In November 1828, at the age of sixteen, he left Ellis and Blackmore’s and set up as a freelance reporter for the Doctors’ Commons. Later described in David Copperfield as a ‘cosey, dosey, old-fashioned, time-forgotten, sleepy-headed little family party’, Dickens was exposed to a range of civil law cases, from the granting of marriage licences to the registering of wills. But the work, when he could find it, was badly paid and no more exciting than that of a solicitor’s clerk.

Miss Maria Beadnell

It was probably through his friend, Henry Kolle, that Dickens became acquainted with the Beadnell family. Kolle was engaged to Anne, one of the daughters of George Beadnell, a successful city banker. Dickens would often accompany Henry to dinner and other social occasions at the Beadnell house in Lombard Street and, by 1830, had fallen madly in love with Anne’s sister, Maria.

Dickens’ mind moved quickly to the topic of marriage and, more importantly, pondering the ways that he could prove himself a viable suitor to the socially superior Maria. Shortly after his eighteenth birthday, Dickens put his first idea into action and applied for a reader’s ticket at the British Museum. He devoted countless hours to furthering his mind, and potentially improving his chances of marrying Maria, through studying Shakespeare, the Classics and British history.

After flirting with his second idea of becoming an actor, the offer of regular work from his uncle’s newspaper, Mirror of Parliament, kickstarted his career as a journalist. In 1832 he was also taken on as a parliamentary reporter with a new evening paper called True Sun. Dickens quickly shone in his new position, establishing himself as an excellent reporter. Spending his days in the House of Commons also developed his social conscience. He became an ardent supporter of the 1832 Reform Act, which increased the number of people eligible to vote in Britain.

In the meantime, his attempts to secure Maria’s hand in marriage were seriously thwarted by her departure to a finishing school in Paris in the winter of 1831. While Mr and Mrs Beadnell found Dickens to be a polite and amiable young man, they had no intention of making him a part of the family and probably hoped that sending Maria away would prevent such a socially unsuitable match. For Dickens, the separation seems to have strengthened his feelings and her absence left him at a genuine loss. During that bleak winter, he spent his evenings aimlessly wandering the streets and observing the people and the comings and goings of the Seven Dials and the slums of St Giles.

Maria did, however, return to London in 1832, exciting a great deal of happiness and hope in Dickens. During his numerous visits to Lombard Street, he was coolly received by the family and struggled to secure time alone with Maria. He resorted to sending messages through various go-betweens, usually Henry Kolle or one of the household maids. At his twenty-first birthday party, he finally got the chance to speak to Maria in private but his declaration of love was coldly rebuffed, prompting him to write in a letter the following:

Our meetings of late have been little more than so many displays of heartless indifference on one hand; while on the other they have never failed to prove a fertile source of wretchedness and misery ... I desire the merit of having ever throughout our intercourse, acted fairly, intelligently and honourably; under kindness and encouragement one day and total change of conduct the next.

A final meeting with Maria occurred on 27 April 1832. Dickens had arranged an evening of theatrical entertainment at his parents’ house on Bentnick Street, to which the Beadnell family was invited. Maria appeared nonplussed by the entertainment, which Dickens had not only written, but also produced and performed. In a final letter, he wrote:

I will openly and at once say that there is nothing that I have more at heart, nothing I more and sincerely and earnestly desire, than to be reconciled to you ... I have never loved and I can never love any human creature breathing but yourself.’ Maria’s reply demonstrated that the cause was truly lost.

Like the Blacking Factory and his father’s imprisonment at Marshalsea, losing Maria was an immensely traumatic experience for Dickens. He would never forget the pain and humiliation of Maria’s rejection, and wrote that the experience imbued him with ‘habit of suppression’, which rendered him ‘chary of showing my affections, even to my children, except when they are very young.’

The Creation of ‘Boz’

December 1833 saw the publication of Dickens’ first piece of creative writing, entitled A Dinner at Poplar Walk. Though he received no payment from the Monthly Magazine for the story, the publication of his work brought him a great sense of pride and achievement. Between January and June 1834, a further four stories, Mrs Joseph Porter Over the Way, Horatio Sparkins, The Bloomsbury Christening and The Boardinghouse appeared in the Monthly Magazine along with the anonymous short story, Sentiment, in Bell’s Weekly Magazine. In August, The Boardinghouse II appeared in the Monthly Magazine, significant as the first work to use Dickens’ pseudonym, ‘Boz’. This originated from the nickname of Dickens’ youngest brother, Augustus, ‘Moses’. When pronounced through the nose, it made the word ‘Boses’ and was then shortened to Boz.

That month also brought Dickens a new appointment as a parliamentary reporter for the one of the most popular newspapers in the country, the Morning Chronicle. Although the post brought Dickens an impressive weekly salary of five guineas (around £230 in modern currency), much of it went to ease his father’s ongoing financial troubles. In September he began work on the Chronicle’s latest creative project, Street Sketches, an illustrated look at life in the city. Through his success at the Morning Chronicle, he was introduced to George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle, and great admirer of his work. Hogarth persuaded Dickens to begin working on a similar endeavour to Street Sketches, called Sketches of London for the Evening Chronicle at an additional two guineas per week.

The final months of 1834 saw Dickens working hard to save his father from another spell in the debtors’ prison. He borrowed money from friends, mortgaged his income and arranged for the family to move to cheaper accommodation at 21 George Street, Adelphi. Dickens did not accompany the family to this house and instead began renting rooms at 13 Furnival’s Inn with his younger brother, Frederick.

Catherine Dickens

A friendship blossomed with George Hogarth and, in May 1835, Dickens became engaged to his eldest daughter, Catherine. While Catherine had the same brown hair, blue eyes and slender frame as his first love, she had a gentler nature than Maria Beadnell, a characteristic that greatly appealed to Dickens. In the same month as the engagement, Dickens moved to Selwood Terrace, Brompton, to be closer to Catherine.

The Early Novels

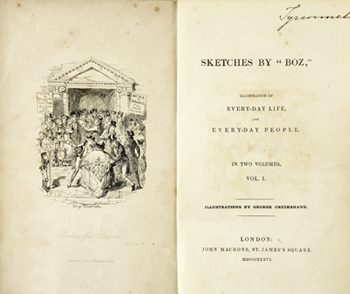

As the Evening Chronicle finished publishing its Sketches of London, Dickens began working on twelve new sketches for the Sunday sporting paper, Bell’s Life In London that included a depiction of life in the Seven Dials. Towards the end of 1835, the publisher John Macrone approached Dickens with the idea of collating his many sketches into a single edition. In return he offered Dickens the sum of £100 for the copyright. Dickens met Macrone through the historical novelist, William Harrison Ainsworth, and this acquaintance is testament to his increasing importance on London’s literary scene. Dickens agreed to Macrone’s offer and George Cruikshank, the well-known caricaturist, was invited to illustrate the two-volume work, Sketches By Boz. It was published on 8 February 1836 and was an instant success; the first step on the road to fame and fortune.

Frontispiece of the First Edition of ‘Sketches by Boz’, 1836

A month after the appearance of Sketches by Boz, Dickens was approached by the publishers, Edward Chapman and William Hall, to write the text for a new series of illustrations by Robert Seymour. With a salary of £14 per month, Dickens accepted without hesitation and persuaded Chapman and Hall to focus the project on his writings rather than Seymour’s illustrations.

On 31 March 1836, the first instalment of the Chapman and Hall project, entitled The Pickwick Papers, was published. The initial print run of 1,000 copies showed only modest sales and the situation was made considerably worse by Seymour’s suicide on 20 September. All parties did, however, decide to continue with The Pickwick Papers. Dickens negotiated a salary increase to £21 per month, and an increase in the amount of writing, from 26 printed pages to 32, with fewer illustrations. In the aftermath of Seymour’s death, Chapman and Hall hired Robert William Buss. Buss was soon fired, owing to the ‘inferiority of his work’ and replaced by Hablot Browne.

In the meantime, Dickens married Catherine at St Luke’s Church in Chelsea on 2 April. A week’s honeymoon in Chalk, Kent, followed and the pair then set up home in the three-roomed flat at 15 Furnival’s Inn. The newlyweds were then joined by Catherine’s sister, Mary.