Полная версия

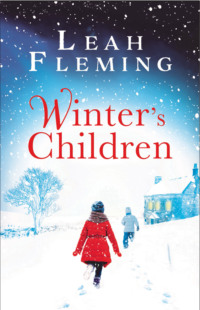

Winter’s Children: Curl up with this gripping, page-turning mystery as the nights get darker

LEAH FLEMING

Winter’s Children

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers in 2010 This ebook edition published by HarperCollins Publishers in 2017

Copyright © Leah Fleming 2010

Cover layout design © Becky Glibbery 2017

Cover photographs © Shutterstock

Leah Fleming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9781847561046

Ebook Edition © November 2010 ISBN: 9780007352487

Version: 2017-08-28

For all the Wiggins, past, present and future who love this season.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Christmas Eve

At the Eve of All Souls

Yorkshire, November 2001

Sutton Coldfield, October 2001

Northbound

Hepzibah Snowden, 1653

Stone Walling

Farmhouse

Anona Norton, 1653

Village School

Quiz Night

A Stormy Forecast

Joss Snowden and the London Painter, July 1816

Christmas Shopping

Agnes, 1869

1874

Shadow Fire

Refuge

Shirley and the German Christmas, December 1946

Understanding

Evie, December 2001

The Search

Christmas Eve 2001

A Jacob’s Join Christmas

Author’s Note

Reading Group Questions

About the Author

By the same author

About the Publisher

Christmas Eve

Sutton Coldfield, December 2000

When the doorbell rang on Christmas Eve, at first Kay and the Partridge family were too busy wrapping up last-minute presents to answer it.

‘Tim’s forgotten his key again,’ Kay shouted to her mother-in-law. ‘Trust him to be home late!’ Since their house had been sold, they were living with Tim’s parents until the move to London in the New Year. ‘Evie, go and open the door for Daddy!’ she yelled to their small daughter, who was as high as a kite on chocolate decorations that had been destined for the Christmas tree. Kay hoped Tim had stopped off at the garden centre to pick one up. He’d promised to dress it with Evie a week ago but the firm had wanted him to go north to secure a deal in Newcastle.

‘Is that you, darling? You’re so … late!’ she yelled down the stairs. There was no response so she trundled down to hear his excuses. Evie was standing at the foot of the stairs looking puzzled.

‘A policeman’s come, and a lady one, they want to speak to you,’ she said smiling. ‘Has Daddy been naughty?’

Kay looked beyond her child to the open door and her knees began to buckle. The expression on the two faces said it all …

At the Eve of All Souls

Yorkshire, November 2001

She glides through Wintergill House, drifting between the walls and closed-up passageways. No floorboards creak, no plasterwork flakes as she brushes past, only a tinge of the scent of lavender betrays her presence. The once mistress of the hearth lists where she wills. She knows every nook and cranny, every dust bowl and rat run, loose boards and lost tokens, cats’ bones crumbling in the roof spaces.

Hepzibah Snowden patrols her kingdom as she did in her own time, keys clanking on her leather girdle, a tallow candle in the pewter hold, still checking that the servants are abed and Master Nathaniel, lord of her nights, is snoring by the fire. She knows her dust is blown into every crevice of the old house, circled by the four winds of heaven. The autumn mists rise from the valley but Hepzibah has no eyes for the outdoors. Her spirit imbues its benign presence only within the confines of these stone walls.

November is the month of the dead. The barometer falls and daylight shortens its path across the sky. She knows the year is beginning its slow dance of death when the leaves curl and rust and sap sink to the roots.

The air is stale, silence reigns. The house is empty of joy. These tenants, an old woman and her son, ignore the patches of damp, the peeling plasterwork, loose slates on the dairy roof. It is a cold, empty and barren hearth. No servants warm their master’s bedpans with hot ashes. No wife warms the master’s buttocks. No horse’s muck steams in the cobbled yard. She hears no shepherd’s cough or stable boy’s whistle. They have made another dwelling of the barn.

It saddens her heart to see all Nathaniel’s toil fall into disrepair. The Lord in His wisdom hath rained down such a plague upon these pastures of late. Now not a living beast bellows from the byre; not a sheep bleats across the meadows. The Lord hath shown no mercy to Godless Yorkshire. All was lost to the summer slaughter in the killing fields below. Now is only silence and tears.

Hepzibah peers out from the window into the dusk. There is another out there she fears. Watching. Waiting. Her erstwhile cousin patrols around the walls, ever searching. The restless spirit who hovers between two worlds. The tortured soul who roams the fells with fire burning in her eye sockets. Blanche is out there in the gathering darkness, waiting to sneak through any open door, seeking what can never be found

Hepzibah shakes her head, safe in the knowledge that this fortress is ringed against this troubled spirit by circles of rowan and elder, by lanterns of light no human eye can see, by sturdy prayer and her own constant vigilance. For she is appointed guardian of this hearth. It is both her pride and penance to stay on within this place.

Each year the two of them must play out this ancient drama with dimmer lights and ever-fading resolve; an endless game of cat and mouse for nearly four hundred years. When, O Lord, will Blanche Norton’s spirit be at peace? Who will help me guide her home?

Soon the yule fires will burn and the seasons will turn towards the light. Hepzibah senses her own powers must fade in a Christmas house without the brightness of a child.

Wintergill House needs new life or it will crumble. It is time now to open her heart for guidance and cast her prayer net far and wide.

Wintergill waits for the coming of another winter’s child.

Yet with such a coming there is always danger, Hepzibah sighs. For if her prayers are granted she must summon her most cunning ploys to protect such an innocent from Cousin Blanche’s consuming fire.

Lord have mercy on Wintergill.

Yorkshire, November 2001

Mincemeat

1 lb Bramley apples

1 lb mixed dried fruit (currants, seedless raisins, sultanas, dates)

8 oz chopped mixed peel

1 lb finely chopped suet of choice

1 lb demerara sugar grated rind and juice of 2 lemons

2 oz chopped nuts, almonds (optional)

1 tsp ground spices (ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon)

4 tbsp whisky, rum or brandy (optional)

Chop the apples, add the lemon rind and juice, and mix with the dried fruits together in a bowl. Add the peel, nuts, spices, suet and sugar.

Stir in alcohol and leave at room temperature covered with a cloth overnight. Restir the mixture. Heat in a low oven for an hour.

Pack into clean, dry jars, cover with wax discs and Cellophane or pretty cloth circles and store in a cool dark place.

Makes about six 1 lb jars.

Sutton Coldfield, October 2001

‘There’s a Place for Us.’ Kay stood transfixed in the supermarket aisle lost in the West Side Story tune in her head until her mother-in-law nudged her with a basket. ‘Oh, there you are, Kay … chop chop! You’ll be late for Evie at the school gate again.’ Eunice was hovering over her. ‘They’ve got a special offer on Christmas cake ingredients …’

‘Christmas already?’ Kay felt the panic rising. It was only October, not yet half term. Her head was spinning at the thought of the coming season. She looked at her watch and knew they must dash. Evie got upset if there was no one waiting for her. After the checkout she pushed her trolley into the car park with a sigh as she looked around the familiar tarmac where a flurry of women were bustling shopping into their boots. Eunice was loitering by the car door with that impatient look on her face.

I don’t want to be here any more, Kay thought. Ever since Tim’s accident she’d been living in a daze of indecision knowing this wasn’t the place for them any more. Then there was that summer painting exhibition in Lichfield Cathedral that still haunted her.

It was just one of Terry Logan’s Yorkshire landscapes: sheep grazing in snow by a stone wall, taking her straight back to Granny Norton’s cottage in the Dales where she’d spent the long summer holidays. Oh, for open space, grey-green hills and daydreaming by the beck … Suddenly she felt such a rush of nostalgia for her childhood. If only she could snuggle back into that dream, back to the old farmhouse set like a doll’s house high on a hill; a house with windows on fire, catching the low evening sun as it drifted across the snow; a sunset of pink, orange and violet torching the panes of glass, a winter house amongst the hills.

She sat in the car with tired eyes averted from the halogen town lights. Always the same haunting dream calling her, tapping into her deepest yearnings. Why was it always the same stone house set above a valley? What did it mean? Was there somewhere waiting for them?

For nine months they had camped out with her in-laws and she could face it no longer. Since the terrible events in America only weeks ago, nothing felt safe in the world. Eunice was protecting them both like lost children … doing her best to keep them close by and Kay had gone along with it for Evie’s sake.

Now with a certainty she’d not felt for months, she knew it was time to move on and away.

‘I need hills around me,’ she whispered with a sigh.

‘What was that?’ Eunice Partridge edged closer.

‘Nothing,’ Kay replied. ‘Just thinking aloud.’

The phone was ringing in the hall of Wintergill House Farm. Let it ring, thought Lenora Snowden as she threw another log in the wood-burner. She was in no mood for a chat, or making mincemeat. What was the point? Christmas preparations were supposed to wrap up the fag end of the year in some festive package. Who could wrap up this terrible season in anything but sackcloth and ashes, she sniffed as she banged the basket of Bramleys on the chopping board.

She inspected the dried fruit, the apples and suet shreds, the box of spices, the cheap whisky, without enthusiasm. Why was she tiring her legs standing on the stone flags in the old still room, now reclaimed as her private kitchen, little more than a cubbyhole, she sighed, choking back the tears.

Things had to go on. The WI needed jars of preserves for their Christmas stall. She always gave to the village school bazaar and the party for the old folks. Though her world had collapsed around her there were still others worse off than herself. She could make a pie for Karen and her boys, who were burying their dad this afternoon.

‘Damn and blast it!’ she muttered, chopping with vigour, as if to release all the tension of the past few months. The dale had never seen such a back end – storms, floods, snow keeping them stuck in for days. Then had come the distant threat of foot-and-mouth, and they’d made a desperate attempt to disinfect and stay protected, all to no avail.

The newly converted barn, which had taken the last of their capital, lay unlet for the whole summer season as the footpaths were closed and the moors cut off. The tourists stayed away dutifully but the bank still required monthly payments on their borrowings. All their diversification plans came to naught.

Chop, chop! She nearly sliced off her thumb in anger. Just when it was all over, just when they thought they’d escaped, when the lambs were gambolling across the fields, a phone call from their neighbours blew Wintergill’s hopes apart.

‘Nora! We’re being taken out! I’m sorry but they’ll be taking you out too …’

Foot-and-mouth had arrived silently across the tops weeks before. The Wintergill sheep were doomed as part of a contiguous cull, but both the cattle and sheep were already infected.

Her eyes were watering recalling those anxious hours. Waiting for the auctioneer to value their stock, a circus of army and vets trampled over their fields. Their death wagons parked up waiting to remove the carcasses, sinister slaughter-men in white suits sweltering in the sun. All she could do was make cups of tea and hide indoors, but the pop of the bolt guns would stay with her for ever, and she was glad her husband, Tom, wasn’t alive to see the destruction of his life’s work.

Nik, her only son, stayed at his post, grim-faced. No amount of compensation would make up for the loss of his prize-winning tups and ewes. They were his life’s work. Now there were green fields but no livestock, proven sacks of feed and nothing to give it to. She was sick of the silence. The heart had gone out of both of them after that day. The bombing of the Twin Towers and all that suffering only added to their gloom that autumn.

Nora sighed, knowing it was easier to hark back to happier times when the making of mincemeat heralded the annual run-up to Christmas: choosing the cards, the gathering for the pig kill. All the old rituals of farm life were going fast. How could they carry on after this? Nik was finished but he did not grasp that there was no future for him now. What was the point, she had argued, and he had stormed off to his part of the house, not wanting to listen to common sense or reason.

So why am I here at my post, chopping apples and grinding spices: cinnamon, ginger root, nutmeg? she mused, wiping her eyes. In her heart she knew she was drawn back instinctively to something ancient and female, soothed by the ritualistic comfort of a seasonal task.

Tosh and bollocks, she sneered, surprised by such sentimental humbug. I’m here because I’ve nothing better to do on this drab morning.

Life must go on and the cooking would take her mind off the funeral this afternoon of a young man who could not face the future without hope.

Since he lost his stock Nik was like a knotless thread, poring over Defra reports on his computer, filling gaps in walls, sorting out his compensation bumf and waiting for the all clear to restock his farm. Six months living on a knife edge of loneliness and despair, and now Jim, his friend, taking his own life just when the worst was over. It didn’t make any sense. It was so unfair on his wife and kiddies, but who said life was fair?

You get what you get and stomach it as best you can, she mused, grabbing her coat and plonking her beret on her head, glancing in the mirror with disgust. You look about ninety, old girl, she sighed, watching the creases and lines wrinkle up her weatherbeaten face. Her country bloom was lost years ago. The mirror had never held much comfort. Her face was too sculpted and her chin too pointed, her tired blue eyes were more like ice than cornflowers, and there were telltale shadows under them from sleepless nights.

All she yearned for now was a quiet hearth and a peaceful retirement. Surely the compensation package would release them now from this hard living. I’ve served my sentence on these harsh northern uplands, battered by winds and wild weather, she argued to herself, bruised by a lifetime of disappointments. Only the turning of the seasons brought life and renewal each year but now time was out of joint. There was no seedtime and harvest, no crop of lambs, no rewards for all their labours, only death and destruction and a tempting cheque. Lenora Snowden could see no future for Wintergill House Farm. It was time to take the money and run.

The phone rang again and the unexpected news she learned sent her scurrying out to the far fields to find Nik. He would be out somewhere avoiding her. It was some good news at last. Perhaps this was the turning point they needed: a sign of hope.

In the far field by the copse Nikolas Snowden was hacking off the branches of a felled ash with a ferocity that satisfied the rage inside him. He knew a chain saw would tackle the job in no time but this was the day for an axe. The physical effort to pit his strength against the ancient trunk was just the challenge he needed to take his mind off this afternoon’s funeral.

He should be beginning to feel a little calmer; quarantine would soon be over and he had been planning his restocking, preparing the fields to restart the cycle with lamb ewes. But his heart was leaden and he felt sick.

He paused to wipe the sweat from his furrowed brow, staring out across the green to the valley below, to the patchwork of grey stone walls rising as far as the eye could see and not a white dot among them. The rooks were cawing down in the churchyard, the curlews had long gone, a flock of redwings were grazing in the distance in the field where his best-in-show tups should have been preparing to service his flock. His eyes filled with tears when he thought of them. They were not just rams, they were old mates, tough proud stock.

How trustingly they had followed his shaken bag of feed nuts as he led them down to their deaths. His ewes were edgy amongst strangers and sheltered their lambs at their side. He had stood with the slaughtermen to the very end, trying to calm their panic on that terrible afternoon when the world was watching the Cup Final indoors, unaware of his terrible betrayal. Like lambs to the bloody slaughter indeed.

It was all in a day’s job for the slaughtermen, but the young vet, new to the job, had the decency to blanch as she grabbed each lamb with her needle. He could hear the bleating panic of his ewes crying, the panic rising as some made a dash for it in vain. And gradually as his flock was destroyed, there was only the silence of a summer’s afternoon, the blaring of the wagon driver’s radio, trying to catch the latest score.

He could see that heap, all he had worked for, piled up lifeless and he’d broken down, unashamed of his grief at such a loss. It was unspeakable the way the diggers scooped up their bodies like woolly rags but he’d seen it through to the end. They were his flock. He had seen each calf born and he must watch them die. It felt like mass murder.

They lambed late in the Dales to avoid the harsh winter and wet spring. It made no odds. How could he have unwittingly nurtured such a disease in his flock? No amount of compensation would ever drive that terrible scene from his mind, or the fact that Bruce Stickley was on the phone minutes after the cull to bid for the valuation of them for compensation.

Nik raised the axe and swung down. It was tempting to give up. The house was a millstone around his neck. His mother was weary. What was the point in all his research, the advice being dished out right, left and centre to the small farmer? ‘Try this, buy that'. Everyone knew there was money in the Dalesmen’s pockets and Nik was wary.

Wintergill had cost him dear; his first youthful marriage had foundered because his town-bred wife, Mandy, couldn’t stomach the loneliness or the harsh winters. Yet he was tied to the place by myriad invisible threads. He was damn near forty-two! Was it too late for life outside the dale? Perhaps he could retrain or retire – and do what?

For God’s sake, this is the only life you’ve ever known, he cried. How do you go on with nobody to follow? Even Jim had taken flight and topped himself, and he had two sons. He had made his own decision. He did not want his children to suffer the burden of being farmer’s sons. It was a terrible solution.

Nik was no longer certain about anything as he looked once more to the beautiful scene before him: how the farm stuck out on a high promontory overlooking the valley and the river snaking through the autumn woods down below; the trees turning into russet and amber and the wind sending storm clouds racing across the darkened sky. The first snows were on their way.

He felt a familiar tingling in the back of his neck. He was not alone.

She was watching him.

Even if he whipped round suddenly he would not see her face, whoever she was, this ancient phantom who wandered over his fields and hid in his copse. There was no comfort in her presence, no benign aura in her haunting. She flitted from lane to wood and moor. Only once had he ever seen her face, years ago, by the Celtic wall when he was young.

‘Bugger off, you old hag!’ he yelled, and swung his axe again in fury.

To be reduced to bagging logs for sale, fixing gaps and repairing machinery – it was no life for a farmer, but it kept his muscles firm and his thighs stretched. He had seen too many of his mates turn to fat in the last few months when reality had kicked in. The bar of the Spread Eagle was a tempting crutch to lean on to sup away sorrows. If he lost his fitness, he would lose what little pride he had left.

Not even his mother knew he could sense stuff with his third eye. It was usually reserved for the female Snowdens to inherit. ‘The eye that sees all and says nowt’ was how his father had once described it. It was not a manly thing to feel spirits up yer backside so he kept quiet about this unwanted gift. If only it had warned him of the danger to his stock.

A movement caught his eye and Nik looked up to see his mother waving from across the gate, calling him inside. What did she want now? He dropped his axe, stretched his back and made for the house. He could do with a coffee and a pipe.