Полная версия

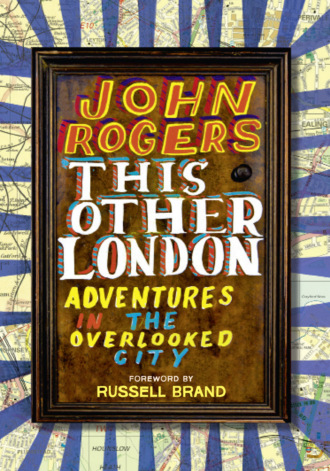

This Other London: Adventures in the Overlooked City

For Heidi, Oliver and Joseph

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword by Russell Brand

Introduction

1 The Wild West – Gunnersbury to Hounslow Heath

2 Off to Bec Phu – Leytonstone to Beckton

3 The Road to Erith Pier – Woolwich Ferry to Crayford Ness

4 Beyond the Velodrome – Lewisham to Tulse Hill

5 The ‘Lost Elysium’ – Sudbury Hill to Hanwel

6 The End of the World on Uxendon Hill – Golders Green to Wembley via the Welsh Harp

7 Wassailing the Home Territory – The Lea Valley

8 Pilgrimage from Merlin’s Cave to the Land of the Dead – Saffron Hill to Hornsey

9 Life on Mars – Vauxhall to Tooting Bec

10 Going Down to South Park – Wanstead Flats to Ilford

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements and Thanks

Copyright

About the Publisher

John Rogers is an important person in my life. As well as being one of my best friends he serves as a navigational point in musings and conversations. Often when discussing the non-negotiable nature of sin my mates and I will say, ‘Well what would John Rogers do?’ As you will learn in these pages John lives in Leytonstone with his two sons and his wife, Heidi, and in spite of the inferred domesticity of that set-up he is a man who lives on society’s margins. Not through occultism or deviance but through his astonishing ability to accumulate and more importantly relay extraordinary information. He is like Prospero crossed with Mr Chips.

I met John in London whilst participating in one of the many half-arsed sub-fringe sketch shows that go on in the capital. We were performing at Riverside Studios in Hammersmith where they used to make TFI Friday. It quickly became clear that the show we were involved in would yield very little and equally clear that John would become a friend for life. John is endowed with a gentle, humble, humorous wisdom, which is evident throughout these pages. You can learn from John on topics as diverse as Marxism, botany, football, punk, astronomy, gastronomy and love. However where John really comes to life is when perpendicular with his boots on. I mean when he’s walking, we don’t have a physical relationship.

Someone once described being in love as like finding a secluded ballroom in the house in which you’d always lived. To walk through London with John is like that. The city is suddenly alive with concealed plaques, submerged rivers and unnoticed gargoyles. John is like an alchemist, not only in that he is unkempt and dresses like a person who has fallen through the cracks, he also makes the mundane and unremarkable glow with newly imbued magic. We once walked through my hometown of Grays in Essex, past the ambulance station at the top of our street, and I instinctively jumped on the knee-high wall to stroll along it as I’d always done as a child. When I told John who was beside me, he said that we could consider memories of a place as objects: left strewn about until we return to collect them.

Once when I was staying on The Strand John, like the tangle-haired shrub shaman that he is, knew all manner of secret doors and passageways that lay unchecked on Fleet Street. We walked through an old, creaking oak door and were suddenly in the quads of Temple. John knew it was there and didn’t care if we were allowed in. This, in fact, is where we saw Thatcher watering roses just months before her death. We went into Lincoln’s Inn, which I never knew existed, and it was like falling down a time tunnel. Not least because a costume drama was being made. Past Aldwych John described two stone giants that adorned a church now used primarily for Romanians, telling me how ‘Gog and Magog’ were Britain’s Romulus and Remus.

Sometimes I think he knows everything. Like most people who are truly wise he never makes other people feel small for not knowing something. John patiently smiles as I tell him all about stuff he knows much more about than me then nods and gently puts me straight. This charming and engaging didacticism is abundantly present in his first book. I am excited that through his writing a wider audience can now share in the joy of John Rogers. That now thousands will, as I have done, begin to understand the character of place, the relevance of history and, most importantly, that adventure is right outside your front door if you’re prepared to take the first step. You, like me, could have no better guide than the man who has written this book.

‘Exploration begins at home’

Pathfinder, Afoot Round London, 1911

Backpacking in Thailand in my early twenties I climbed down off an elephant in a small village in the mountains of the Golden Triangle. The streets of 1994 East London felt far away – I had broken free for new horizons. I entered a small wooden hut where a villager prepared freshly mashed opium poppy seeds in a long pipe. In Hackney such men were called drug dealers – here they were known as shamans. ‘Across the rooftop of the world on an elephant’, I wrote in my travel journal. The flight to Bangkok had been the first time I’d been on a plane; my previous travels hadn’t extended beyond a coach trip to Barcelona. The top of this mountain was the edge of my known world – the real beginning of an adventure.

In the gloom of the hut was another group of travellers – fellow explorers and adventurers. I spoke to the pale, willowy girl sitting next to me, dressed in baggy tie-dye trousers, a large knot of ‘holy string’ on her wrist from a long pilgrimage around India. She told me stories about an ashram in the Himalayas and gave me the address of a man with an AK47 who could smuggle me across the border into Burma. A few more minutes’ conversation revealed that this wise-woman of the road was an accountant on sabbatical who lived two doors down from my sister in Maidenhead. I had come 6,000 miles to a remote mountainous region to sit in a shack with a group of Home Counties drop-outs chatting about a new Wetherspoon’s in the High Street.

Hostel dorms were full of wanderers who claimed to have ‘discovered’ beaches and villages merely because they weren’t in the latest Lonely Planet Guide, ignoring the fact people were already living there. Seemingly there was nowhere left to ‘discover’, the whole world was very much ON the beaten track. I spent two years bunkered down on Bondi Beach but longed for windswept, collars-up London evenings, to be in this city indifferent to the whims of the individual, a slowly oscillating hum of existence, to feel millennia of history squelching beneath wet pavements. I also missed a decent pint of beer that wasn’t served in a glass chilled to the point that it stuck to your lips.

Returning to London and eventually starting a family didn’t mean settling down. I usually wear walking boots and carry a waterproof jacket just in case I spontaneously head off on a long schlep towards the horizon. I’ve remained on the move.

One Sunday winter evening I travelled five stops on the Central Line from Leytonstone to Liverpool Street to walk along the course of the buried River Walbrook. I didn’t see a soul until I popped into Costcutter on Cannon Street to buy a miniature bottle of Jack Daniels to drink on the pebble beach of the Thames beside the railway bridge. The backpacker trail had been as congested as the rush-hour M25, whereas the pavements above a submerged watercourse running through the centre of one of the biggest cities in the world were deserted. If I’d taken an afternoon stroll in the Costwolds I’d have been tripping over ramblers at every field stile, but here I had the streets to myself, the only other people I saw were the snoozing security guards gazing into banks of CCTV monitors. This walk, inspired by an old photo I’d seen in a book bought in a junk shop of a set of wooden steps leading down from Dowgate Hill, had led me to a land twenty minutes away from my front room more mysterious than anything I’d encountered in Rajasthan or the Cameron Highlands.

Randomly flicking through the pages of an old Atlas of Greater London a new world revealed itself. The turn of a wad of custard yellow pages and there was Dartford Salt Marsh reached by following the Erith Rands past Anchor Bay to Crayford Ness. Skirt the edge of the Salt Marshes inland along the banks of the River Darent, down a footpath you find yourself at the Saxon Howbury Moat.

This atlas of the overlooked was richly marked with names written in italics that would be more at home on Tolkien’s maps of Middle Earth in The Lord of the Rings than in the Master Atlas of Greater London. Hundred Acre Bridge should be leading you to a Hobbit hole in The Shire rather than to Mitcham Common and Croydon Cemetery. Elthorne Heights and Pitshanger sound like lands of Trolls and Orcs but where the greatest jeopardy would be presented by my complete inability to read a map or pack any sustenance beyond a tube of Murray Mints.

I set out to explore this ‘other’ London and pinned a One-Inch Ordnance Survey map of the city to the wall of my box room. It felt unnecessary to enforce a conceit onto my venture such as limiting myself to only following rivers, tube lines or major roads. I also didn’t fancy the more esoteric approach of superimposing a chest X-ray over the map and walking around my rib-cage. I wanted to just plunge into the unknown – ten walks, or what now appeared as expeditions, each starting at a location reached as directly as possible with the fewest changes on public transport, then hoof it from there for around ten miles, although it’d be less about mileage and more about the experience. I’d aim to cover as much of the terra incognita on the map as possible, spanning the points of the compass and crossing the boundaries of London boroughs as I had done borders between countries.

It was essential to embark on this journey on foot. For me walking is freedom, it’s a short-cut to adventure. There’s no barrier between you and the world around you – no advertising for winter sun and cold remedies, no delayed tubes or buses terminating early ‘to regulate the service’. Jungle trekking in Thailand and climbing active volcanoes in Sumatra were extensions of walking in the Chilterns with my dad as a kid, and wandering around Forest Gate and Hornsey as a student. Through walking you can experience a sense of dislocation where assumptions about your surroundings are forgotten and you start to become aware of the small details of the environment around you. At a certain point, as the knee joints start to groan, you can even enter a state of disembodied reverie, particularly with the aid of a can of Stella slurped down on the move.

When you walk you start to not only see the world around you in a new way but become immersed in it. No longer outside the spectacle of daily life gazing through a murky bus window or ducking the swinging satchel of a commuter on the tube, on foot you are IN London.

The explorations I’d carried out over previous years had taught me to expect the unknown, to never deny myself an unscheduled detour, and that even the most familiar streets held back precious secrets that were just a left-turn away. Most of all I knew that the more I gave in to the process of discovery the more I’d learn.

I’d initially been inspired to head off travelling round the world by reading the American Beat writers who gallivanted coast-to-coast across America looking for a mysterious thing called ‘It’. After finally landing in Leytonstone I wondered if enlightenment was just as likely to be found on the far side of Wanstead Flats as at the end of Route 66.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.