Полная версия

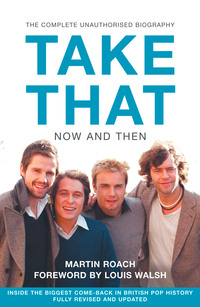

Take That – Now and Then: Inside the Biggest Comeback in British Pop History

TAKE

THAT

NOW AND THEN

THE COMPLETE UNAUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY

INSIDE THE BIGGEST COME-BACK IN POP HISTORY

MARTIN ROACH

Dedicated to Kaye and Alfie Blue

Table of Contents

Cover

Titlepage

Dedication

Foreword by Louis Walsh

Introduction

A Wish Away

Who Cares Wins

The Fuses Are Lit

Something Remarkable This Way Comes

The Magic Numbers

I Can't Believe What I'm Seeing

The Golden Years

‘I Don’t Even Like Melon!’

Nobody Better

Gone For Good?

Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes

Open Roads, Endless Possibilities

The Phoenix Unfolds

Chalk And Cheese

People In Glass Houses

Play To Win

Back With The Boys Again

Afterword

Back For Good

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword by Louis Walsh

Take That were the best boy band in the world. They were the reason I started Boyzone—Boyzone were the Irish Take That. I thought Gary and the band were absolutely brilliant. They appealed to everybody, their records were great and they had everything: great ballads, great up-tempo numbers, amazing live shows—I saw them at The Point in Dublin and the sound, the lights, the choreography, the entire show was just amazing.

Then, of course, you had Nigel Martin-Smith, who did a fantastic job managing them. He made Take That special: people weren’t always allowed near them, they weren’t accessible everywhere, hanging out at nightclubs all the time with every Page Three girl, like so many boy bands today. Nigel made them special and that had an awful lot to do with their success.

Robbie has become successful and he is a great performer…a huge success. I admire his work ethic. He’s a fantastic worker who knows how to appeal to both girls and boys. I have been known to criticise him, but he is so ambitious and I would never underestimate Robbie. He knows exactly what he is doing.

Meanwhile, Take That are still selling out stadiums, which is incredible. Their records are still on the radio, their TV documentary was fantastic and they are still so popular. For me, they totally provided the blue-print for that genre.

They will always be England’s best boy band.

Louis Walsh

February 2006

Introduction

Within twelve months of announcing their ‘reunion’ tour in late 2005, Take That had completed the biggest come-back in pop history. At the time of writing they can sell tickets faster than any other pop artist in the UK; they have topped the singles charts two more times and produced one of the biggest selling albums of the last decade; their own TV special enjoyed one of the highest ratings for an entertainment show in years…it seems there is no limit to what they can now achieve.

How have they done it?

On the surface, there are three key reasons. Firstly, the cultural impact from their original career has proved to have far longer lasting resonance than anyone—probably even the band themselves—realised. Pop is a fickle beast and for a band in that genre to have any lasting validity is unusual. Take That was not a pioneering fashion band, far from it. They were not musical innovators. They were certainly not the critics’ band of choice. Yet what the colossal success of their come-back tour tells us is that they clearly made an indelible mark on British music and cultural history. The broadsheets might not like to think so, but it is a fact. Among the thousands of bands that spilled out of the Nineties, the importance of the majority would fade with time. Take That’s legacy, however, was clearly a sleeping giant.

This pop behemoth was first awakened by an ITV1 documentary and then established on the high streets of Britain by a series of come-back shows that captured the nation’s imagination on an unprecedented scale. The band’s famously energetic and explosive original live shows have been surpassed by a new tour of stunning proportions. Filling some of the UK’s biggest venues was one thing, entertaining in them quite another. They did both with aplomb. Why would so many thousands of people chase tickets to see a band from their childhood? Partly because they wanted a good time; partly because the shows themselves were sensational; but mainly because to millions of people, Take That matter.

Finally, the band has produced an album of new material that is genuinely polished, well-crafted and hugely popular. A live show alone does not qualify Take That for the accolade of pop’s biggest come-back. Of course, nostalgia plays a part, but the band has brilliantly complemented this revival with a slew of superb new songs. Opening single ‘Patience’ was a new classic in the ‘Back For Good’ vein, while follow-up ‘Shine’ was an addictive curve-ball. Both were No. 1. The album, Beautiful World, silenced all but the very harshest of critics.

That, it appears, is how they have done it.

It is rare for a pop band to get a second bite of the cherry—rarer still for any come-back to have greater commercial potential than the first time around. That’s what Take That appear to have done. The biggest pop band of the Nineties can now add the biggest come-back in pop history to their list of achievements.

From childhood days in bedrooms writing songs, to thanking audiences of 60,000 in football stadiums over twenty years later, this is how it all happened…

Martin Roach March 2007

A Wish Away

Gary Barlow was washing his Ford Orion outside his parents’ house when his mum shouted that someone was on the phone for him. It was a local model-agency owner called Nigel Martin-Smith whom Gary had been to see that very afternoon. The 19-year-old Gary had wanted to speak with Nigel about getting small acting roles now that he had an Equity Card. At the end of their meeting, Gary had given Nigel a demo tape of some songs he’d been writing and recording in his bedroom.

Drying his hands, Gary picked up the phone.

‘Hello Gary, it’s Nigel Martin-Smith here. I’ve listened to that tape you gave me and I just wondered who is singing on it?’

‘It’s me, Nigel.’

‘OK, but who is playing the music and made the arrangements and everything?’

‘I did, Nigel, I did it all in my bedroom.’

‘Er…right. Can you come back to see me straight away, Gary? Tonight…’

At that precise moment, Take That, arguably the biggest British boy band ever, was born.

***

Regardless of Gary’s latter-day solo success and irrespective of the public’s perception of Take That’s key players, it is a simple fact that the very heart of the band always was—and always will be—Gary Barlow. Of the thirty-three original tracks on the band’s three studio albums, Gary was solely credited for writing twenty-five of them and co-writing a further seven.

Born 20 January 1971, Gary shares his birthday with punk svengali and cultural icon Malcolm McLaren, twenty-five years his senior. He was brought up in Frodsham, Cheshire, a small town with some big money, filled with sandstone brick buildings, a couple of housing estates, an old church, scatterings of hills and good walking country. It has been said that Frodsham people think they are a bit above their neighbours—and they are, overlooking as they do the chemical and petrol plants around Runcorn.

Gary was born to parents Marge and Colin Barlow, with one older brother, Ian (who now runs his own building firm). As a baby, Gary cried so much that his mother wondered if there was something seriously wrong with his health, but then they realised he was just a tiny baby who liked to make a lot of noise. His primary education was at Weaver Vale, where a final-year primary-school production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat saw him take the lead role. However, the first real signs of a future life in entertainment came when Gary was just 11 years old and chose a keyboard for Christmas, having been given the choice of either that or a BMX bike. Remarkably—and there are numerous first-hand sources to back this up—the pre-teen Gary was very quickly writing his own material.

Gary’s school life carried on at Frodsham High School, where his mother was a science technician. Perhaps surprisingly, given his young age, the schoolboy Gary had started performing professionally at social clubs in the local area. At this early stage, in true Phoenix Nights-style, he incorporated a handful of jokes into his routine. Notably, his musical influences were generally older than those of most teens—although his first record was ‘Living Next Door to Alice’ by Smokie, he was a big Motown fan, and liked artists such as Elton John and Stevie Wonder. His main song-writing inspirations were The Beatles and Adam Ant, an odd mix but obviously not one that stifled his creativity.

As early as age 13, Gary was playing solo every Saturday for ?8 a night at Connahs Quay Labour Club in North Wales, performing classic working-men’s standards such as ‘Wind Beneath My Wings’. He’d been offered the job after coming second in a talent competition at the venue with a cover of the surreal classic, ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’. Gary’s slot at the Labour Club lasted two years, during which time he also formed a duo with a friend known only as Heather. Together they played the pubs and clubs circuit for a further two years. He also formed a short-lived band inspired by Adam and the Ants. His rudimentary keyboard was soon replaced with a £600 organ with foot-pedals, which offered the budding songwriter far more musical possibilities.

One of the most significant jobs he secured was a ‘residency’ fronting a small, middle-aged band at the Halton British Legion in Widnes, near Runcorn, which included four gigs every weekend until well after midnight. By then, the mid-teenage Gary was earning up to £140 a night, which was no small accomplishment. Inevitably, late working hours and early school schedules were exhausting for him, but all he wanted to do was play and write and perform. He even gave up his beloved karate lessons because he broke his fingers twice and was concerned about jeopardising his piano-playing.

Gary supported some notable performers, including Ken Dodd and Bobby Davro, and, perhaps more importantly, began to slip his original compositions into his set alongside the staple club standards. One of those original songs had taken him six minutes to write and was entitled ‘A Million Love Songs’. Another two were called ‘Another Crack in My Heart’ and ‘Why Can’t I Wake Up with You?’.

By this stage, Gary would spend any spare time he had writing new material. On quiet weekends he’d aim to write and demo one song a day at home, a challenge he often completed. This prolific drive, cooped up in his bedroom, was balanced with the practical experience of weekly gigging. The Legion was an ideal sounding-board for his song ideas, and also a priceless three-year apprenticeship working both with the public and veteran musicians, especially for a boy who was still twelve months shy of taking his O levels when he started. The ‘pie-and-mash circuit’ might not be the most glamorous of jobs, but there is no better way to breed new talent.

It’s hard to trace back to when a pop star has his first big break, but undoubtedly when Gary entered a song for the BBC Pebble Mill’s competition ‘A Song for Christmas’, and promptly reached the semi-finals, it was a watershed moment. He was only 15. His mother had been largely unimpressed with his self-penned ballad ‘Let’s Pray for Christmas’, but his music teacher entered it into the competition for him.

It was during a gym lesson that Mrs Nelson interrupted Gary to tell him he had been selected by the BBC to go into the next round of ‘seniors’. This involved travelling down to London’s West Heath Studios to record the track in full. It was the first time he’d been inside a recording studio but he was a natural and made full use of the orchestra and backing vocalists on offer. The whole experience was filmed, and watching the clip back now it is hard to imagine that Gary was only four years away from starting the biggest boy band of the Nineties. Although Gary’s track stalled at the semi-finals stage, he won a modest amount of prize money, which he promptly utilised by going into 10CC’s Strawberry Studios in Stockport to demo some more of his own material.

During his time in London, Gary had met several famous agents and music-business executives, so his ‘showbiz networking’ had begun. However, his path to stardom was far from smooth. Eager to get a potentially lucrative publishing deal—effectively selling his songs for other performers to sing—Gary scoured London’s record labels looking for someone who thought he was capable of writing a smash hit for their artists. Among the usual polite rejections, Gary tells a story about one executive who listened to ‘A Million Love Songs’, scornfully ripped the tape out of the machine and slung it through the open window into the street, ending his bizarre tantrum with the warning that Gary should never darken his door again. Gary has, over the years, resisted what must be the great temptation to reveal this executive’s name.

Meanwhile, Gary’s secondary education was unremarkable, with no major dramas: he was a good student and passed six ‘O’ levels, with his parents keen for him to work in banking or the police force.

***

Given their roles in Take That, it is interesting to note that two of the first members to start the chain of events leading to the band’s formation were Howard and Jason. The oldest of the band, Howard Paul Donald, was born on 28 April 1968 in Droylsden, Manchester (Howard is almost four years older than the baby of the band, Robbie Williams). Howard was from a large family, with three brothers (Michael, Colin and Glenn) and a sister (Samantha), as well as his father Keith and mother Kathleen. Both parents were entertainers, Keith teaching Latin American dance and Kathleen being a gifted singer. His parents later separated and he is also close to his step dad, Mike.

Surprisingly, Howard’s first ambition was to be an airline pilot. He went to Moreside Junior School for his primary education, where reports suggest he was a good student. His time there was not without its dramas though: ‘A couple of weeks after I started school, I got this disease called impetigo. When I was off school, this teacher put a big sign on my desk saying “Don’t Go Near This Desk!” When I told my mum, she drove up to the school and went mad!’

Howard’s first album was by Adam Ant and, like his future band-mate Gary Barlow, he was a big fan of the Dandy Highwayman. However, as his teenage years rolled by, he became fascinated with an altogether different style of music—break beat and hip hop. In turn, this relatively new genre introduced him to dancing—break-dancing in particular—and with this new obsession came a declining interest in academic matters.

Break-dancing is an extraordinarily athletic and acrobatic style of movement and dance that at the time was a central part of hip hop culture, emerging as it did out of that movement in the South Bronx of New York City during the late Seventies and early Eighties. It can actually be traced back to 1969, when James Brown’s ‘Get on the Good Foot’ inspired famously acrobatic dance moves, and simultaneously Afrika Bambaataa started organising one of the first break-dance crews, The Zulu Kings. The relevance to Take That might seem tenuous, but by the early-to mid-Eighties, hip hop and break-dancing had been exported across the Atlantic and imposed itself on the daily lives of British youth. School yards were filled with teenagers spinning on old pieces of lino, hip hop clothing labels were worn and break beat music blared out of oversized ghetto blasters—suburban Britain doesn’t have too many ghettos like the Bronx, but that wasn’t the point. It was a style, a look and a sound that became immensely popular. Howard was exactly this type of break-dancing Brit, and he lived for it. He often played truant so he could practise his moves, which increasingly included complex gymnastics, so that by the time he was 15 he was a very adept dancer indeed. According to an interview with Rick Sky for The Take That Fact File (one of the few writers to have covered the band from before they were famous), he once absconded from school for five weeks in a row: ‘I only intended to have a few days off, but I kept taking another day, then another day, till the days had run into weeks. I got into awful trouble for that.’ He later admitted to being caught graffitiing a bus, although that appears to be the extent of his ‘waywardness’. Like Gary, he also bought an electronic keyboard, but his main passion was for dancing.

Despite his latter-day persona as the quietest member of Take That, Howard was something of an extrovert at school—break-dancing was hardly the domain of the class nerd, after all. This obviously provided plenty of distraction, because he left school without a single ‘O’ level to his name. He wasn’t altogether troubled by that, not least because he had just been enrolled in a local break-dancing crew called the RDS Royals.

It was 1986 and Britain was in the grip of the Thatcher years. Unemployment was over the three million mark, social unrest was rife and many people, particularly the young and less privileged, were isolated and disillusioned. Behind all the politics and histrionics, the reality for 16-year-olds with no qualifications, like Howard, was simple: either unemployment or the last bastion of state-sponsored slave labour, the Youth Training Scheme, or YTS. Howard took a job painting cars for £40 a week, and he was still working there when he first auditioned for Take That.

He started to supplement his feeble income by dancing at clubs such as Manchester’s Apollo, on podiums and stages to vibe the crowd up. It was an ideal way of getting paid to practise, and besides, if he wasn’t working at these clubs he would have been there as a paying punter anyway. Consequently he developed a very muscular physique at an early age, leading to his latter-day Take That nickname of ‘The Body’.

***

One of the people in Howard’s break-dancing circles was Jason Orange, the older of twins by twenty minutes, born 10 July 1970. Coming from a similarly big family, as well as Jason’s twin Justin there were four other brothers (Simon, Dominic, Samuel and Oliver) with his (now divorced) parents, bus driver Anthony and doctor’s PA Jennifer, bringing the family total to seven. Jason is reputed to have ‘blue blood’ in his veins—family trees suggest he is a direct descendant of King William of Orange, a Dutch Royal plagued by ill health who sat on the British throne as King William III in the second half of the seventeenth century.

The Orange family were Mormons, a faith shared by other pop stars including The Mission’s bacchanalian front man Wayne Hussey and The Killers’ Brandon Flowers. Like Flowers (and very much unlike the rock-and-roll beast that is Wayne Hussey), Jason’s family eschewed caffeine and alcohol as ‘drugs’ and lived very clean lives, something which Jason was able to continue even under the extreme pressures of being in a world-famous boy band.

Like Howard, Jason was not academia’s biggest fan. Attending at first Havely Hey School in Whythenshawe until he was 12, and then South Manchester High School, Jason was a keen sportsman, being particularly proficient at swimming, running and football. He has said that he was a quiet pupil and kept himself to himself, so it was perhaps not surprising that when he reached 16 he chose to leave school with only a modest amount of exam passes. On his final day at school, he walked through the gates for the last time, turned around, surveyed the buildings where he’d spent so many years and shouted ‘Freedom!’ out loud. He was keen to work and also joined the infamous Youth Training Scheme, which placed him as a painter and decorator for the Direct Works department of the local council (likewise his twin Justin). Typically, this involved decorating council property and amenities buildings.

It was hardly the most glamorous of work, and although Jason enjoyed it for the four years he was on an apprenticeship there, he had his sights set on greater things. In his first teenage year, Jason had also become fascinated with break-dancing—after a brief dalliance with Pink Floyd, whose The Wall was the first album he ever bought—so that by his late-teens every spare minute outside of work was spent practising, performing in the streets and watching American videos of the big-name dancers. He joined a local crew called Street Machine that was effectively a rival to Howard Donald’s RDS Royals. He too started working the clubs, and this was how he first met Howard at the Apollo. With so much in common they were bound to spark off each other, and a tight dancing partnership was soon formed by the name of Street Beat, which proved to be increasingly lucrative. They could soon command a week’s YTS money for one night’s work.

Progress was swift for both dancers, who started to rack up television work as well as regular jobs on the club circuit. Jason performed regularly on the TV show The Hit Man and Her, presented by Pete Waterman and Michaela Strachan. He’d got the gig after his girlfriend had written to the show telling them of his talent (along with his friend Neil McCartney). Howard, meanwhile, had the technically more impressive but rather less street-credible accolade of performing on that mainstay of conservative TV schedules Come Dancing, during sections of the show dedicated to modern dance.

Realising their dancing was proving very popular and that there might be a good long-term living to be had beyond the nine-to-five they were used to, Howard and Jason paid a visit to a local music impresario by the name of Nigel Martin-Smith. Unbeknown to them, their lives would never be the same again.

***

Hailing from the far-from-rock-and-roll town of Oldham in Greater Manchester, Mark Owen was the first future Take That member that Gary Barlow would come into contact with. The product of a northern Catholic family, Mark was born on 24 January 1972 (sharing his birthday with Neil Diamond) and grew up with his brother Daniel and sister Tracey in a modest council house, sharing a room with them for much of his childhood. Such small redbrick terraces were archetypal Mancunian accommodation, made famous by the opening credits of Coronation Street.

Mark’s parents, Keith and Mary, first sent him to be educated at The Holy Rosary Junior School. Mark was a good sportsman, being particularly adept at football despite his relatively diminutive frame, standing at just five foot seven inches tall. One local team he joined, Freehold Athletic, voted him Players’ Player of the Year several times, including one season where he scored a hat-trick in a cup final. (’That day will stay with me for as long as I live.’) Music Industry Five-A-Side football tournaments are testament to the fact that Mark has lost none of his silky skills, nor his quiet, sportsman-like manners.

But his skills were not always so smooth: ‘I got told off all the time for playing football in the house. I broke two windows in one day once. Just as they were fixing the one at the front of the house, I broke the one at the back of the house!’ When he broke a window another time, he went and bought a pane of glass to carry out a hasty repair. Unfortunately, his glazing skills weren’t quite up to his football ones and his parents came home to find his hands cut to ribbons because of his well-intended but ultimately doomed attempts to repair the window.