Полная версия

The Magic of Labyrinths: Following Your Path, Finding Your Center

Jung’s fascination with the primordial imprinting that leads us to seek a spiritual or religious explanation for the world around us, and our role within it, was expressed through his drawings. It is said that every morning he would sketch small circles as representations of his inner state that day. Jung noticed how these circles, such as the mandalas used as meditation tools by eastern mystics – as with labyrinths – brought everything to a single central point. The great psychoanalyst’s interpretation of this universal motif was that it symbolized the Self’s incessant journey towards higher meaning and purpose.

Likewise, the labyrinth is a universally imprinted archetype or theme illustrating our life’s journey towards spiritual development and completion. As you will discover later in this book, it can be used as both a personal tool and one that unites communities, thus fuelling our sense of Oneness with our environment.

One Mind, Many Applications?

There is a complementary view that also bears mentioning. One that may also explain the mysterious origins of the labyrinth and that similarly speaks to our psychological need to feel part of a whole. This alternative view helps to demonstrate that we are not so different from peoples who lived on this Earth 10, 20, 30 or even 40,000 years ago. Indeed, contemplating the enduring facets of human nature helps to reinforce the relevance of the labyrinth as an archetypal symbol that is as psychologically valuable to us today as it was way back when.

Much of our popular historical knowledge cloaks the fact that considerably more early crosscultural contact took place than was once thought. For example, most children are taught that Henry the Navigator or Christopher Columbus “discovered” America in the fifteenth century. Some may even have heard of Amerigo Vespucci or John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) who, controversially, claimed to have preceded them. This completely disregards evidence that expeditions to the New World had been undertaken by peoples originally from Siberia (c. 70,000–9,000B.C.). Other suggested early explorers of the Americas, with varying degrees of evidence, range from Indonesians (c. 6,000–1,500B.C.), the Japanese (c. 5000B.C.) and Afro-Phoenicians (c. 1000B.C.–300A.D.).

Certainly, some archaeologists and historians now believe that the Vikings may have traveled down from Newfoundland to New England and even reached North Carolina. And it seems likely that these expeditions were not all one way, given the record of two Indians having been shipwrecked in Holland around 60B.C., causing considerable interest and excitement at the time. There are many other examples that provide a richer view of history than most of us were taught at school.

Given that there was considerable cross-cultural contact between peoples much earlier than we have been led to believe, this can be linked with contemporary evidence for the way ideas originating within one small group can spread like wildfire. Hence, we can see how a symbol such as the labyrinth could have come to enjoy such universal popularity from a single source.

Today we call it “viral marketing” or “buzz,” but basically it is old-fashioned word of mouth. In his book The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell outlines three criteria or rules for the proliferation of social epidemics and he discusses how certain messages, behaviors, ideas, and their products spread like infectious diseases. The concept of a labyrinth, stemming from a single source, meets all three of these criteria.

First, you need a small number of people with both the creativity to understand the impact of a new idea and the personal magnetism or charisma with which to promote it. Such people in early times were called “shamans.” Shamanism, said to be the world’s oldest religion, spiritual discipline and medical approach, originated in Siberia – and it was here that a labyrinth carving was found, dating back over 7,000 years. The shaman worldview offers an experiential path to knowledge, gained through the process of ritual, meditation and a concept of trials or tests that is akin to the Hero’s journey through the labyrinth (see chapter 3). Like the labyrinth, while variations exist between cultures, the concept of shamanism is very similar whether in the Americas, Africa, and Australasia or Lapland, Malaysia, and Peru.

The shaman’s role within a society was to straddle the world of reality and the world of spirit. As such they demonstrated that all-important psychological need which is now being explored more actively through environmental and spiritual groups – that of the interdependence and unity of nature and humankind. Interestingly, the shaman did not simply represent the Divine, as priests and other religious figures do. The shaman is Divine, in the way that we have been urged to think of ourselves by many prophets and philosophers, such as the fourteenth-century Christian mystic, Meister Eckhart, who said:

Here, in my own soul, the greatest of all miracles has taken place. God has returned to God.

In the same way that the simple act of walking or tracing a labyrinth can unite body and spirit, the shaman demonstrated the spiritual affinity between plant, person, and place.

Malcolm Gladwell’s second criterion explaining why certain concepts can spread rapidly across societies is that of “stickiness.” By this he means the extent to which a message is memorable and impactful. Since Jung, together with Eastern mystics before him, have presented the image of life as a journey with a single pathway leading in to the center, it is not surprising that the labyrinth motif would have appealed to anyone who came into contact with it.

Given the potential of the labyrinth as a way of explaining the world and how we should best act on it, it can be imagined that one or a number of Siberian shamans found that this particular tool – a portable “mental map,” simple to construct and easy to explain – helped them disseminate their worldview to other cultures. This may have happened in the same way that the “peace symbol,” the original concept of one man, spread from being used in materials and on marches by the UK’s Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, to being a worldwide icon of peace. Being simple to produce and an image that resonated with billions of people around the globe, the peace symbol – like, possibly, the labyrinth – was one person’s idea that “stuck.” It was a local idea that fast became a global phenomenon.

The third criterion is “the power of context.” Here again, we can relate back to Jung’s hypothesis for the universal power of archetype and myth. The notion of something so simple yet complex as a labyrinth is as compelling to us in the twenty-first century as it was to our earliest ancestors. There is no reason to suggest that they would not have been concerned with the same big, philosophical questions that we still grapple with today – Why are we here? What is the purpose of our lives? What happens when we die? Like us, they would have wanted to better understand life and the purpose of it – and, in particular, how to feel happier and more fulfilled on this lifelong journey.

The psychologist, Abraham Maslow, formulated a hierarchy of needs in which security issues (such as the provision of shelter and food) are at the base of the triangle, with self-actualization (spiritual needs) at the pinnacle. However, this seems to over-simplify the human experience and before Maslow died he admitted that he might have got this the wrong way around. Just because prehistoric people had more pressing security concerns than most of us in the West today, that does not mean that they did not also seek deeper meaning and purpose in their lives.

The manner in which our ancestors explored these issues was through myths and there is considerable similarity in these stories, regardless of the culture. Indeed, rather than accepting that religious writers accessed the power of the collective unconscious, it may be that they borrowed and modified much earlier stories for which the power of context was universal. For instance, there is considerable similarity between archetypes appearing in the Assyro-Babylonian poem the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 700B.C.) and the Old Testament of the Bible. Both feature a serpent, a woman who robs a hero of his innocence, and someone who survives a Great Flood.

LABYRINTHS AND MYTH

The labyrinth has long been associated with myths and legends, the most direct link being with the story of Theseus and the Minotaur (see here). But why should we be interested in centuries-old accounts of the exploits of fictional gods, goddesses and heroes? More particularly, why would they hold any relevance to us today?

Mythology is populated by archetypal characters who illustrate universal dispositions with which each one of us can relate at various times in our lives. Despite the culture or period in which these mythological tales were written, each one of us recognizes in them universal values around being and behaving. Within an oral tradition, myths ensured the values of a culture were broadcast from generation to generation. They also helped explain fundamental but complex philosophical issues in a way that was more palatable and easily understood – through stories about the adventures and lives of gods and heroes.

For example, no concept intrigues, terrifies, and holds us in awe more than death. Death has been the subject of introspection and debate since the earliest times when bodies, whether of Egyptian pharaohs or Neanderthal nomads, were buried with everything they might need for their next journey, into the “land beyond.” We are fascinated by death from an early age when we ask, unsuccessfully, for confirmation of exactly what happens to us. I remember an occasion when we buried a goldfish in the back garden and my small son pressed me to tell him where it would go. Thinking I was being suitably spiritual in my instruction, I assured Graeme that the goldfish would go to heaven to be with God, only to find my son digging up the area the next day to check whether the fish had got there yet.

The labyrinth is typically associated with dark caves, the inner workings of our subconscious and the way in which we must constantly review our attitudes and behaviors so that we “kill off” any that are no longer useful to us in order to resurrect or discover ones that are. Not surprisingly, the labyrinth motif has been woven into a number of myths concerning death. Such myths also elaborate on the key role of women in the human experience. For example, Joseph Campbell relates the myth of the Malekula islanders in Vanuatu (formerly the New Hebrides) in the South Pacific who learn that their approach to the Land of the Dead will be halted by a female guardian. She draws a labyrinth design in the earth, then erases half of it and the soul’s task is to complete the design perfectly before they will be allowed to pass through to the underworld. If they do not, then they will be eaten by her.

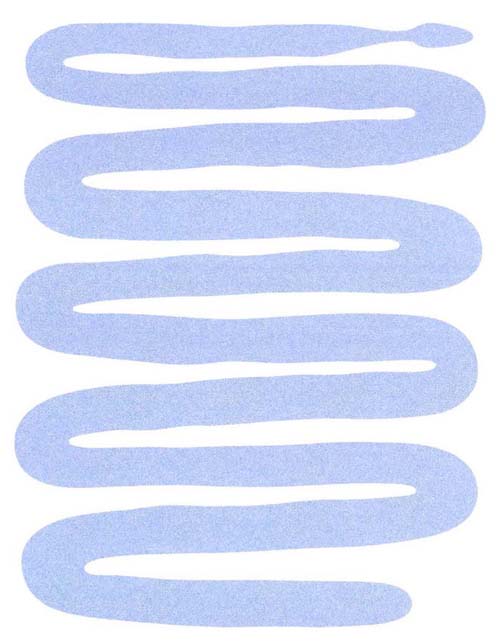

Unlike mazes with their dead ends, labyrinths are reminiscent of coiled snakes. According to the Hindu tradition, Kundalini is the serpent goddess who awakens whenever an individual embarks upon a spiritual journey. As they proceed on their path, overcoming challenges in the way of the hero, Kundalini journeys upwards, piercing each chakra in turn until, reaching the crown chakra, the subject is said to have achieved spiritual enlightenment. (For more on this, see here.)

Snake-like Imprints

Then there is a tale that comes from Arnhem Land in Australia’s Northern Territory which is the aboriginal equivalent of the Biblical story of Noah’s flood – only, as in many non-Christian examples, the story involves female protagonists, not a male one. Two sisters, one already a mother and the other pregnant, are forced to leave their home and begin to journey north. As they travel they give names to everything they see, bringing the stone animals, plants and insects to life. These women belonging to the Wagilag clan, camp alongside the Mirarrmina watering hole, unaware that it is the sacred home of the Giant Python, Wititj.

Angry at being disturbed, Wititj sucks up all the water and spits it out to form monsoon clouds that break and flood the land. The sisters begin to perform songs and dances in order to divert the waters. But the serpent swallows them and their offspring whole, raising himself into the sky to escape the deluge. In the heavens, he is admonished by his ancestors and they tell Wititj that he should not have swallowed all members of the same family. The great snake becomes ill and crashes to the ground, leaving a labyrinthine imprint in the earth, whereupon he spits out the women and children. Wagilag men who have followed them, learn of the songs and dance rituals performed by the women to halt the flooding and these are enacted during the monsoon season to ensure the continuation of nature’s cycles.

In Arnhem Land, the giant python Wititj was said to be responsible for the cycle of the seasons.

Goddess Worship

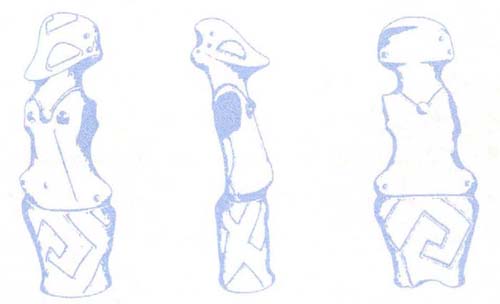

The links between the labyrinth symbol and goddess worship – the means through which early people expressed their love and respect for Mother Earth – are strong. The meander pattern (see here), from which the Classical seven-circuit labyrinth may be derived, has been found on bird goddess figurines dating back to c. 18000-15000B.C. by Lake Baical in the Ukraine. Additionally, rituals engaged in across Scandinavia (where the largest concentration of labyrinths from antiquity can be found) involved males competing with each other to see who can reach the female in the center first. These games, conducted most frequently in eleven-circuit labyrinths, were very different from the formulaic rituals of the seven-circuit Troy Towns. Indeed, there is a suggested link between the number 7 and male energy and the connection between the number II and female energy (see here).

Bird goddess figurines from the Ukraine showing characteristic meander patterns.

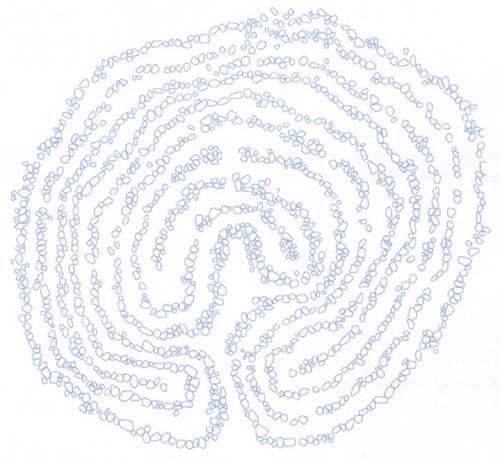

Within the eleven-circuit stone labyrinths that proliferate throughout Finland and Sweden the goal of negotiating the labyrinth involved rescuing a young woman at the center. At Kopmanholm, to the north-east of Stockholm in Sweden, there is a stone labyrinth known as the Jungfruringen or “Virgin’s Ring.” This particular design has two entrances, one going in from the left, the other from the right. The game involved two young men racing to the center to see which one of them would reach the maiden first. A number of suggestions have been made as to what this game signifies. One is that the female in the center represents Helen, the acclaimed beauty over whom the Greeks and Trojans went to war. Another is that “saving the girl” is a metaphor for young men reclaiming their female energy in order to become whole human beings again. This pagan symbolism has also been found on a wall of a fifteenth-century church in Nyland, Finland where a painting of a labyrinth depicts a virgin waiting at the center.

Labyrinths in Popular Culture

In fairy stories, while labyrinths or mazes are seldom implicitly mentioned, the notion of the Prince hacking his way through a dense, complex forest in order to reach the Sleeping Beauty, is just one metaphor for the trials and tests one must engage in to reach a prized goal. Indeed, many such stories involve the protagonists enduring a series of tasks – for which they appear initially unprepared – that suggest a journey to find their female side (the “princess”) in order to become complete human beings.

The Jungfruringen or Virgin’s Ring, Sweden, with its two entrances. Young men would race each other to reach the maiden in the center first.

Given the richness and complexity of the labyrinth as a metaphor for life, this motif has captured the imagination of writers, most of who allude to intricacies or entanglements of one sort of another. In Troilus and Cressida, Shakespeare writes: “How now Thersites? What, lost in the Labyrinth of thy furie?” The poet Shelley opined: “From slavery and religion’s labyrinth caves, Guide us.” And from W.B. Yeats: “Does the imagination dwell the most, Upon a woman won or woman lost? If on the lost, admit you turned aside, From a great labyrinth out of pride.”

In the world of popular fiction, labyrinths – explicit or allegorical – appear in the likes of Mervyn Peak’s Gormenghast novel Titus Groan, in the description of the Stone Lanes region; as the Mines of Moria in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and in Terry Pratchett’s Small Gods with the “booby-trapped labyrinth of Ephebe.” J.K. Rowling has even incorporated a maze in the Tri-Wizard Tournament, that her hero must navigate at the end of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.

But my favorite example of a labyrinth in a book is in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, described as a dark, contemporary Alice in Wonderland. In the story, an ordinary man named Richard Mayhew becomes trapped in London Below and must negotiate the labyrinth and its beast in order to reach and vanquish the ultimate enemy – an angel who has “gone bad.” Mayhew alone succeeds where others (traditionally more powerful) in his party fail, despite losing the talisman that he had been told would ensure his safe passage through the labyrinth. After successfully killing the beast, our hero is told to apply its blood to his eyes and tongue so that he can negotiate the passages with ease.

The wonderful message of this part of the book is that facing and disposing of the “monster within” – a concept Jung referred to as our “shadow” – is a precursor to converting the journey from a puzzling maze into a labyrinth. By doing this, your way becomes “straight and true” during which you know “…instinctively every twist, every path, every alley…” Thus, Gaiman reminds us, tackling the inner Beast – whether that be our fears, our self-neglect, our cowardice or denial of reality – allows us to navigate life’s journey by tapping into our inner compass or intuition. In this way we discover that life’s path involves an easier and more straightforward approach than we originally thought. (For more on how we can change our own lives from resembling mazes to becoming more like labyrinths, see here.)

Also worth mentioning in this context is the movie Labyrinth, Jim Henson’s dark, allegorical tale of a teenager who wishes her annoying baby brother would be taken away by goblins – and he is; a classic case of “beware of what you wish for.” Our heroine, Sarah, is then given thirteen hours to rescue the boy, before he is turned into a goblin. She accomplishes her quest, which superficially involves solving riddles and a race against time, but in essence it concerns the process of growing up and discovering what is really important in life.

Labyrinths and Christianity

It may seem surprising that a symbol so obviously associated with pagan beliefs came to find its way into so many Christian churches. However, the taking over of pagan symbols and ideas was something the Roman Catholic Church engaged in extensively. For example, pagan communities tended to celebrate festivals every six to eight weeks, to mark the changing seasons and solar cycles. Because these were so well established throughout northern Europe, particularly in Britain, many were simply overlain with Christian symbolism. Hence, Yule or the winter solstice became Christmas, Samhain became All Saint’s Day, and the spring equinox became Easter. The latter festival, incidentally, is named after the German fertility goddess Eostre or Ostara, which comes from the same root as the female hormone oestrogen. Not surprisingly, given the fertility link and the nature of female reproduction, the symbol of Eostre is an egg – hence the notion of Easter eggs, which was a custom engaged in by pagan communities long before Christianity came on the scene.

Indeed, it has been argued that the Christian figure of Mary, mother of Jesus Christ was recreated from the ancient concept of the Great Mother Goddess in her triple archetypal roles of Virgin, Mother, and Wise Woman. There were certainly plenty of precedents for virgin births among the pre-Christian pantheon of Gods. The oldest of divinities, Gaia, appeared out of nothing to give birth to Uranus, the starlit sky, while the patriarch of the Greek gods was originally called Zeus Marnas or “Virgin born Zeus.” Any number of Greek heroes, including Perseus who slayed the Gorgon Medusa, and Jason of Argonaut fame, were said to be virgin born. The reason why the Christian church has resisted the worship of Mary as anything other than the earthly mother of Jesus was because she was based on a composite of many pagan goddesses. However, by giving this archetype a role to play within its religion, the Catholic Church ensured that their new, monotheist, patriarchal religion became relevant to people who were polytheist and largely matrifocal. As well as re-defining the Mother Goddess as the Virgin Mary, the Church changed many other pagan deities into saints. In one example, the Celtic goddess Brighid became St. Brigit (or Brigid).

In the same way that the Holy Roman Church appropriated existing pagan archetypes and festivals, it built its places of worship on sites which ancient peoples had long revered for their sacred energy. Many churches in England were built on “ley lines” (the phenomenon of electromagnetic energy sometimes called Earth “chi”) because the only way the Catholic church could integrate non-Christians into their own religion was to appropriate the sacred sites at which they already worshipped.

The labyrinth is a wonderful tool that engages people easily and that can be used to address deeper issues around spirituality and the best way to journey through life. So, instead of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, the Christian Church appropriated it for its own needs. The Christian church could not change people’s long-held faith, so they simply Christianized it. In the process, to set theirs apart from pagan examples, church labyrinths became more intricate in their design and ornate in their execution. They also became associated with Biblical cities, such as Jerusalem and Jericho – the latter possibly deriving from the Roman view of labyrinths as a kind of fortified city.

Contemporary Labyrinths

Aside from all the wonderful examples of labyrinths springing up around the world today – many of which we will read about in later chapters – this ancient symbol is proliferating on that most modern of tools – the Internet. If you are interested in the use of the labyrinth as a device in on-line and other interactive games, the World Wide Web will lead you, labyrinth-like, to the key resources.

One particularly inspiring use of the labyrinth on the computer is the on-line Lenten labyrinth. Professor Paula Lemmon teaches beginner’s Latin classes at the Southwestern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. For the last two years (at the time of writing), her department has created an on-line Lenten labyrinth for which the students are charged with providing translations (from Latin into English) of various classical and religious texts. The 2001 project is totally interactive, with twelve candles pointing the way through this ancient devotional tool in order to illuminate the images and words contained within. Traditionally linked to the concept of pilgrimage by the Christian church (see here), the Lenten labyrinth allows the Web pilgrim to scroll through the Chartres design to read excerpts from medieval Latin texts (including Ovid’s Fasti), accompanied by images of the Holy Land that were created by the nineteenth-century painter, David Roberts in 1842. These images come from the archives of the University’s Bridwell Library, which holds a world-renowned collection of classical theological and other texts. This is the first time that images from David Roberts’ Holy Land folio have been digitally distributed, and presents a rare opportunity to see his work (see Resources).