Полная версия

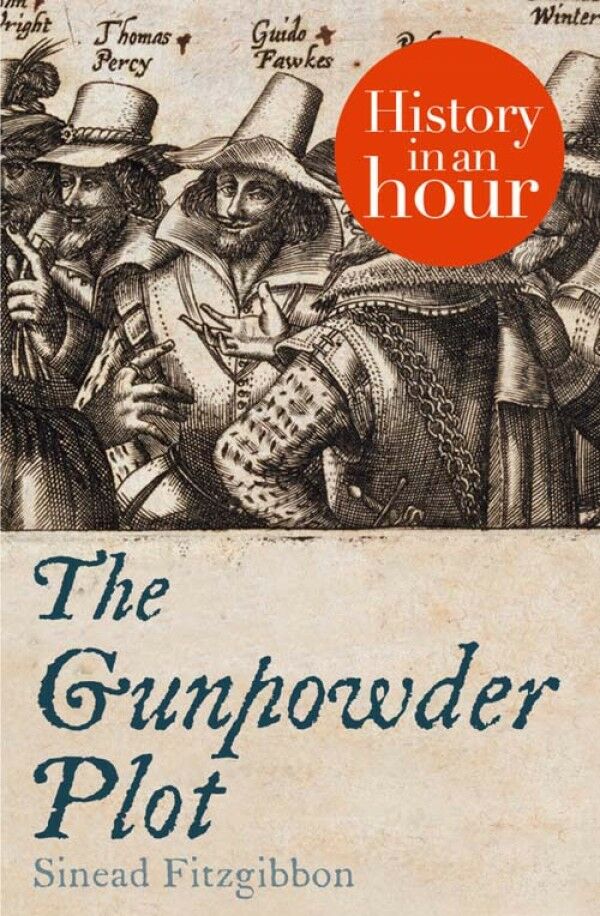

The Gunpowder Plot: History in an Hour

THE GUNPOWDER PLOT

History in an Hour

Sinead Fitzgibbon

About History in an Hour

History in an Hour is a series of ebooks to help the reader learn the basic facts of a given subject area. Everything you need to know is presented in a straightforward narrative and in chronological order. No embedded links to divert your attention, nor a daunting book of 600 pages with a 35-page introduction. Just straight in, to the point, sixty minutes, done. Then, having absorbed the basics, you may feel inspired to explore further.

Give yourself sixty minutes and see what you can learn …

To find out more visit http://historyinanhour.com or follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/historyinanhour

Contents

Title Page

About History in an Hour

Introduction

A Country Divided

The Conspirators

The Hatching of a Plot

The Discovery

An Attempt to Escape

Torture and Capture

Trial and Execution

Repercussions, Traditions and Legacy

Appendix 1: Key Players

Appendix 2: The Gunpowder Plot Timeline

Copyright

Got Another Hour?

About the Publisher

Introduction

Remember, remember, the fifth of November,

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot.

I see no reason why Gunpowder Treason

Should ever be forgot.

Like all good conspiracy stories, the tale of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 is one that combines elements of mystery, intrigue, suspense and, of course, deception. It is the story of a small band of disaffected Catholics who, unhappy with the constraints placed on their religion by Elizabeth I and her successor, James I, decided to challenge the religious and political status quo. They would do this by committing the ultimate act of terrorism – the destruction of both king and Parliament. The plan was audacious and surprisingly simple – and came very close to succeeding. There have been innumerable terrorist conspiracies, both successful and otherwise, down through the ages, but the Gunpowder Plot has succeeded in capturing our imagination unlike any other. Over 400 years has passed since this daring scheme was discovered, and yet its legend continues undiminished. Every year, bonfires are lit the length and breadth of Britain to mark the Plot’s anniversary, a tradition which dates back to that fateful November night in 1605 when the Gunpowder Plot was uncovered at the eleventh hour.

This, in an hour, is the story of the Gunpowder Plot.

A Country Divided

England at the turn of the seventeenth century was a country rife with political tensions and religious divisions, the roots of which can be traced back some seventy years to the reign of Henry VIII. The actions of this one man would have profound repercussions for his kingdom, condemning his people to decades of religious conflicts and persecution. The discord which resulted from Henry’s exploits would in turn give rise to one of the most audacious terrorist plots this country has ever seen – the Gunpowder Plot.

Henry VIII

During the early 1530s, Henry, in his desperation to marry Anne Boleyn, was frantically looking for a way to divorce his wife of almost twenty-five years, Catherine of Aragon. When numerous appeals to Rome for an annulment fell on deaf ears, Henry’s patience began to wear thin. Powerless in the face of the Pope’s authority, Henry grew increasingly resentful. Until this point, Henry had been a dutiful and pious Catholic. Despite this, relations between the English monarch’s court and Rome were invariably strained. Henry, accustomed to being in an authoritative position, often found it difficult to bend to the will of the Papacy. Ever the opportunist, the King’s attentions soon turned to the Protestant Reformation which at the time was sweeping the Continent.

Henry VIII

Recognising in this movement a chance to circumvent the authority of Rome, Henry began to endorse the Reformation’s ideals. Thus began a concerted campaign to wrest power from the Papacy. Denouncing the Catholic Church as corrupt and out of touch, Henry broke all ties with Rome in 1533. In doing so, he proclaimed himself, and not the Pope, to be the Supreme Head of the Church in England; the King was now bound only by his conscience in matters of religion and theology. Conveniently, his conscience proved to be no obstacle to his divorce from Catherine.

So began a marital merry-go-round which would last for more than a decade. Proving himself to be a fickle husband and obsessed with producing the necessary male heir, Henry would marry six times. These marriages would end by a variety of means: divorce, death or execution. They would, however, produce three children: Mary from his marriage to Catherine of Aragon; Elizabeth from his union with Anne Boleyn; and the longed-for son, Edward, from his third marriage to Jane Seymour. Henry’s offspring would each play a significant part in inflaming the religious tensions which were first ignited by their father.

Edward VI and Mary I

When Henry died in 1547, his youngest child and only male heir, Edward, ascended to the throne to become King Edward VI. He was only nine years old at the time of his coronation. Brought up in the new faith, Edward, together with his Protestant guardians, earnestly continued with Henry’s programme of reform. Under Edward’s reign, Henry’s policy of dissolution of the monasteries was completed. This left the Church all but bankrupt, with most of the wealth transferred to the King’s coffers. The reign of Edward VI, however, was not destined to last long. A sickly child, the young king died in 1553 at the age of fifteen. He left behind a country where the Church of England had become quite firmly established. This, however, was all about to change with the ascendancy of his half-sister Mary to the throne. During the turbulent years of her father’s religious reforms, Mary, Henry’s eldest child, had managed to retain her Catholicism in the face of severe opposition. In fact, it could be said that the harsh treatment of her mother, Catherine of Aragon, at Henry’s hands had only served to harden Mary against the very idea of Protestantism. Her unquestioning devotion to her mother’s religion was set in stone. It is hardly surprising, then, that when Mary became queen, she quickly set about accomplishing her long-held ambition of restoring England to the Catholic faith.

Unfortunately, in her zeal to undo all her father’s reforms, Mary revealed a hatred for Protestantism that was all-consuming. She regarded all adherents to the new religion as heretics, and displayed no compunction in burning at the stake those suspected of harbouring Protestants or with Protestant leanings themselves. In all, 237 men and 52 women met a painful end during Mary’s reign. This willingness to kill in the name of Catholicism gained her a reputation for mercilessness that would rival her father’s. History would not judge Mary’s actions in promoting the old faith kindly – she would be remembered for centuries to come as ‘Bloody Mary’.

Elizabeth I

After Mary’s death in 1558, the last of the Tudor children came to the throne. Like Edward before her, Elizabeth’s sympathies lay with the Protestant cause, and so her coronation saw the pendulum swing once again back to the Protestant religion.

Elizabeth I

A year later, in 1559, the Act of Supremacy and the Act of Uniformity were introduced, reinstating into law many edicts which had been repealed by Mary I. The Acts declared the celebration of Mass and other Catholic traditions illegal, while also enshrining Elizabeth’s supremacy over the Church of England. These new laws introduced fines for those who refused to attend Church of England services; abstainers were known as recusants. These measures were designed to make life very difficult for Catholics in England, and for the most part they succeeded in their aim. Catholic disillusionment set in, and the situation would soon worsen.

In 1570, in reaction to Elizabeth’s draconian measures against the Catholics in her realm, Pope Pius V issued the Papal Bull, Regnans in Excelsis. This missive ex-communicated Elizabeth from the Catholic Church, and as such absolved all Catholics of their allegiance to their Queen. In effect, the Papal Bull declared that Catholics had a duty to God before their monarch. This proclamation did little to improve conditions for the beleaguered Catholics of the Elizabethan era. All Catholics were now viewed as potential traitors to the Crown, effectively sanctioned by Rome.

The inexperienced Queen, fearful of uprisings against her authority, introduced more legislation. In a bid to prevent Catholics receiving religious instruction, priests were denounced as traitors and banned from English shores. Anybody found guilty of sheltering priests, or providing assistance to them in any way, would also be subject to the full force of the recusancy laws. Where once Catholicism was simply illegal, it was now regarded as high treason. Elizabeth did not hesitate to use this new legislation to her advantage; it soon became clear that she was as adept as her sister Mary at executing religious opponents and heretics.

These measures, however, failed in their ultimate aim of eradicating the Catholic threat; in fact, they succeeded only in forcing Catholics underground. While some priests did flee the country, many decided, in defiance of new laws, to remain in England. The fight to save the Catholic faith was aided by the arrival of hundreds of foreign-trained priests. The majority came from the English seminary in Douai, northern France – a college founded by the Jesuits in 1568 to instruct Englishmen in theology and provide training for priests. In all, over 450 priests arrived in England from foreign shores, of whom 130 were executed for their efforts to administer the Catholic faith. One such priest was Father Edmund Campion.

A Protestant by birth, Campion had won a scholarship to Oxford at the age of fifteen. His immense intellectual abilities earned him a fellowship of St John’s College, Oxfordand a deaconship in the Anglican Church. However, he secretly harboured sympathies with the Catholic faith and, in 1571, stole away to Douai to study with the Jesuits. After his conversion to Catholicism and his ordination as a priest in 1580, Campion returned to England on a mission to support his fellow clergymen. After a year spent travelling around the English countryside, he was finally arrested by Elizabeth’s men. He was brought to the Tower of London and tortured. Refusing to denounce his faith, he was sentenced to death in 1581. If Elizabeth hoped his execution would damage the morale of the Catholic crusaders, she was to be sorely disappointed. Instead, his death elevated him to a Catholic martyr and the circumstances of his death inspired Catholics to re-double their efforts in the face of Protestant persecution.

The survival of priests during this difficult time would not have been possible without the protection of the recusant population. Proving themselves to be just as undeterred by the threat of the recusant laws as the priests, many of the subjugated Catholic population were willing to help defy Elizabeth. Catholic women, in particular, became central to the Catholic resistance movement. Regardless of the danger to themselves, they provided priests with vital support in the form of food and shelter, often concealing them in their own homes. Hiding places or ‘priest holes’ became a feature of recusant households, saving many members of the Catholic clergy from the gallows. Despite the constant danger, many continued to practise their Catholic faith in secret.

As the gulf between Catholics and Protestants widened, a pervasive and insidious atmosphere of fear and suspicion descended upon the population, which was to provide a fertile breeding ground for the radicalization of the disaffected Catholic minority.

James I

Following the death of Elizabeth in 1603, the crown passed to the incumbent Scottish king, James VI. As the grandson of Henry VIII’s sister, James had a legitimate claim to the English throne, and was therefore met with little opposition from the English. In fact, his ascension was one of the smoothest and most uncontentious transitions to power the country had ever seen. One of his first acts as King James I of England was to introduce the Union of Crowns, whereby he declared Scotland and England to be united under one monarch.

James I

Despite the fact that the new King was a confirmed Protestant – having being brought up in a strict Calvinist tradition by Church of Scotland ministers – many of the country’s disaffected Catholics believed that James’s arrival on the English throne would herald an improvement in their fortunes. This optimism was based on James’ strong familial connection to the old religion: his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had been a devoted Catholic. The early signs were very encouraging: when James initially relaxed the fines levied on recusants, the Catholic population was overjoyed.

But the euphoria was short-lived. When he realized that his over-extended Treasury was heavily reliant on income from recusant fines, the King quickly re-instated them. Following this, James made a speech outlining his distaste of the superstitious Catholic faith. It had become clear that James was disinclined to leniency on the Catholic question, and the hopes of many were disappointed. Now, tensions which had long been simmering bubbled to the surface. A group of provincial Catholic noblemen decided the time had come to end this State-sponsored persecution and to take a stand against their oppressors.

The Conspirators

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the secretive nature of their endeavour, the noblemen involved in the ill-fated Gunpowder Treason were initially few in number – in fact, only five men were privy to the initial planning stages of the scheme, a number which would increase to thirteen by the time the Plot reached its dramatic conclusion. The majority of those implicated were related, through blood or by marriage, to the most prominent Catholic families in England – the clans of Throckmorton, Vaux and Monteagle. They were a tight-knit group of brothers, cousins and close friends who were united against a common enemy, each harbouring a deep-seated sense of injustice at the loss of their religious freedoms.

Robert Catesby

The ringleader of this band of brothers (and principal architect of the Gunpowder Plot) was a man named Robert Catesby. The only surviving son of Sir William Catesby, a notorious recusant, and his wife Anne Throckmorton, Robert had a high Catholic pedigree. He also had first-hand experience of the suffering and hardship caused by Elizabeth’s stringent recusancy laws. From a very young age, he had witnessed his father’s frequent imprisonments for his refusal to submit to the new religious convention. He also saw his family’s fortune dwindle as a result of the heavy fines levied on them. These early experiences heavily affected the young man, who would bitterly resent Protestant authority for the rest of his life.

Catesby’s religious proclivities were well known to the authorities, as were his rebellious inclinations. When Elizabeth I fell ill in 1596, Catesby was rounded up and imprisoned, along with other prominent recusants (some of whom would go on to become involved with the Gunpowder Plot). This was to prevent Catholic dissenters from taking advantage of the Queen’s sickness to mount a rebellion. He was released upon the Queen’s return to health.

2nd Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux

The full extent of Catesby’s subversive inclinations first manifested themselves in 1601 when he became embroiled in the Essex Rebellion. The uprising was a failed attempt to overthrow Queen Elizabeth’s council of advisers, spearheaded by the 2nd Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux. Essex, an erstwhile favourite of Elizabeth, had recently fallen out of favour at court, and his rebellion was a desperate attempt to re-establish himself in a position of authority. The scheme was ill-conceived, and never seemed likely to succeed.

However, the recklessness of the endeavour did not deter Catesby. He willingly threw his lot in with the insurrectionist in the hope that, if successful, Essex would work towards improving conditions for the Catholic minority. The role Catesby played in the uprising is unclear, although it is safe to say that it was relatively minor, given he escaped with his life. Essex was not so lucky – he was found guilty of treason and executed. Catesby was fined a substantial sum for his part in the rebellion, which forced him to sell some of his property, namely his estate at Chastleton in Oxfordshire. Unchastened by his experience in Essex’s rebellion, it soon became clear that its failure had done nothing whatsoever to assuage his revolutionary aspirations.

A handsome and charismatic man, Catesby was well liked and inspired intense loyalty among his friends. He also held considerable sway over his extensive family, a fact he often exploited to maximum effect – many of those who became involved in the Gunpowder Plot did so out of a misguided personal loyalty. Thanks to his mother’s familial connections, Catesby’s far-reaching recusant kinship produced a complex network of cousins from whose ranks he would recruit his co-conspirators.

Among those who had the misfortune to fall under Catesby’s spell and thus found themselves implicated in the Gunpowder Plot were Catesby’s first cousin and childhood friend, Francis Tresham; brothers Robert and Thomas Wintour (also cousins of Robert Catesby), and their brother-in-law, John Grant. Others who proved themselves fatally susceptible to Catesby’s charm were Jack and Christopher Wright, together with their brother-in-law Thomas Percy. Ambrose Rookwood, Sir Everard Digby and Robert Keyes were also devotees who would be only too willing to foolishly follow their seditious leader down a path to self-destruction. Catesby’s faithful servant, Thomas Bates, was yet another who found himself mixed up in the deadly scheme by virtue of his unfailing loyalty to his charismatic master.

Guy Fawkes

But perhaps the most famous of the conspirators, and the name which has become synonymous with the legend of the Gunpowder Plot, is Guy Fawkes. Although Fawkes was involved with the Plot from its inception, it was not him, but Catesby, who was the chief instigator of the conspiracy. In fact, Fawkes was an outsider among the scions of English recusant families – his only connection to the group being the fact that he attended school with Jack and Christopher Wright as a young boy.

From the very beginning, it was clear to Catesby that if his scheme were to succeed, he would need a man with a working knowledge of gunpowder to join his close-knit circle. Guy Fawkes was an obvious choice. He had spent twelve years as a mercenary soldier in the Catholic King of Spain’s Army of Flanders, fighting against Protestant insurgencies. It was during these religious wars on the Continent that Fawkes had gained extensive gunpowder expertise. He had also acquired a reputation for being a devoted Catholic of dependable character, attributes which convinced Catesby that Fawkes was the right man for the job. Tom Wintour was despatched to Flanders under orders to secure the soldier’s co-operation. Much to Catesby’s relief, Guido Fawkes (as he was then known) proved to be a willing recruit – he landed in England in April 1604, ready to take up the Catholic cause.

The Hatching of a Plot

Tom Wintour was the first of the conspirators to learn of Robert Catesby’s intention to mount a rebellion against the Protestant establishment. It is likely that he was made aware of the scheme sometime during the early months of 1604. He could have been in no doubt as to his cousin’s objectives when he travelled to Flanders in April to recruit Fawkes on Catesby’s behalf. Unsurprisingly, Wintour initially baulked at the very suggestion of such a dangerous and destructive scheme. He argued, quite sensibly, that if the uprising failed in its objective, it would result in an exacerbation of an already fraught situation, and quite possibly set the Catholic cause back by many years. His logic was quickly discounted by Catesby, who declared that ‘the nature of the disease requires so sharp a remedy’. In a bid to dispel Wintour’s doubts, Catesby launched into an impassioned defence of his deadly scheme, declaring Parliament to be a legitimate target in the fight to end Catholic persecution. ‘In that place’, he said, ‘they have done us all the mischief’.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.