Полная версия

The Artist’s Problem Solver

Divide the paper or canvas into thirds, vertically and horizontally. Where the lines cross, these are the ‘eyes’ of the rectangle, perfect spots on which to position a focal point or area. My diagram shows all four, but you would only use one, ideally, for your main focal point.

Divide the picture into two, from corner to corner. Then bring a line down from one of the other corners, to cross the first line at right angles. Where the lines cross, is the ‘eye’ of the rectangle, or focal area. In my diagram you can see two alternatives.

HOW TO POSITION YOUR FOCAL POINT

You should always aim to direct the viewer’s eye into and around the picture. Therefore, the placing of the main elements of the picture is crucial. Artists through the centuries have used the ‘golden section’ – a way of dividing the rectangle that is somewhat complicated, but worth exploring (see Bernard Dunstan’s book Composing your Paintings published by Studio Vista). A simpler way is to divide your rectangle as in either of the diagrams above. Placing the focal point onto one of the ‘eyes’ will be both successful and comfortable.

L’ESCARGOT

pastel on paper, 41 × 51 cm (16 × 20 in)

Although the shell looks fairly central, in fact I placed it carefully within the rectangle so that its sharply sunlit right-hand edge, and its shadow, were positioned in the lower right focal area of the rectangle. The flowers, in reality, were a different colour – I chose to use orange, the complementary colour to the blue-greys of the iron shell.

THE HURVA SQUARE CAFÉ, JERUSALEM

pastel on paper, 51 × 61 cm (20 × 24 in)

This was a difficult composition, since the café seats stretched across the scene, but I decided on a dominant focal area of the bench, table, silhouetted figures and two umbrellas on the left. The umbrellas are sharply defined by the light area behind. The lines of paving, and the tree trunk, lead to the focal point, about one third into the picture.

HOW TO EMPHASIZE THE FOCAL POINT

Deciding where to put the focal point is just the beginning. Although this will help you to begin your picture with confidence, since everything else should slot happily into place around the focal point, sometimes that focal point fails to attract attention. There are several devices you can use to ensure that the focal point commands the viewer’s attention properly:

Strong contrasts of tone: If you place your lightest light area in the picture next to your darkest dark area, this will inevitably command attention, since this will be an area of great visual tension and drama – just what you want.

Strong contrasts of colour: By placing vivid complementary colours next to each other – blue next to orange, red next to green, or yellow next to purple – you will draw the viewer’s eye to this point in the picture. If you use colour contrasts to draw attention to a focal point, the colours you use must be in key with the rest of the picture, so that they do not jump out in isolation, and should be gently echoed in other areas.

Dominant shape: A main, large shape in the picture will command attention – but be sure to integrate this shape with the rest of the composition, by echoing it with less dominant but similar shapes elsewhere, or perhaps by softening edges in places.

Direct the eye with ‘lead-ins’: Directional lines, implied lines, and points with an image can be used to gently lead the viewer to the focal point. For example, a pathway might lead up to a group of figures; the light-touched tops of clouds might bring the eye down to an important tree in the middle distance. In a still life, the edge of a table, or frame of a picture on the wall in the background might direct the eye to the bowls and jugs on the table. Becoming aware of shapes, and edges, within a rectangle, instead of thinking solely about the physicality of the objects featuring in the scene, is a big mental step to take, but a vital one to encourage the development of your sense of design.

Using a viewfinder: You will find it really helpful to use a viewfinder. We tend to ‘see’ our subjects, particularly landscape subjects, landscape shape. Yet a tall focal point may be much better expressed in portrait format. Make thumbnail sketches of the view. Feel free to adjust elements within the scene, to emphasize or echo the focal point – you could shorten a tree, for instance, if it is exactly the same size as the church, your focal point.

SUMMING UP

In his book Composing your Paintings, Bernard Dunstan says: ‘It is dangerous, although tempting, to isolate the different aspects of painting from one another … everything in a picture that looks as if it could be taken out and examined as a subject by itself turns out to be dependant upon, and modified by, many other factors’. So although I have offered you a few basic ideas here about the focal point in relation to the composition of a picture, please be aware that it is only a small, if important, part of the whole painting.

TWO GARDEN CHAIRS

pastel on paper, 51 × 61 cm (20 × 24 in)

It is obvious that the foreground chair is the focal point of the picture. The shadows on the ground lead us in from the bottom edge of the rectangle to the chair, and the light tones of the chair contrast strongly with the dark surroundings. The second chair, repeating the angles of the first, provides an effective pictorial echo.

3

CREATING DEPTH

I have difficulty in creating a sense of depth in my paintings. How can I achieve the effect of depth so that they appear more realistic?

Answered by: John Mitchell

There are several ways in which you can suggest depth: perspective, tone, overlapping, and weight of texture or line. In practice any picture will use a combination of these.

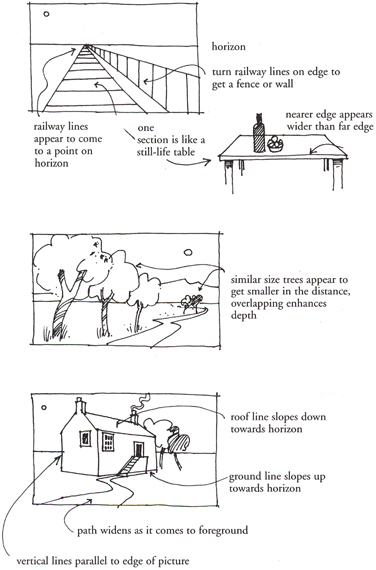

Perspective is probably the most obvious way to suggest depth. Unfortunately, it can become confusing with expressions like ‘vanishing points’ and ‘height lines’. So let us try to keep it simple.

These drawings demonstrate easy approaches to perspective. Practise by drawing matchboxes seen from different angles and follow this up in thumbnail sketches like these. Perspective is the main method of getting depth into paintings.

LINEAR PERSPECTIVE

Objects appear to get smaller as they get further back in the picture space. So a tree in the foreground will appear higher than a similar tree in the background. We all know about the effect of looking along straight railway lines as they run towards the horizon – they appear to come to a point. You can also get this effect by looking along the length of a table with your eyes at table height. Not only, therefore, do objects get shorter in the distance, they also appear to get narrower.

So far so good, but it gets a bit trickier with roof lines – how do we know when the line should run uphill or downhill? A common mistake is to make part of the drawing or painting look as if it has been seen from eye level and the rest from a helicopter. An obvious example is when a chimney top is drawn from above and the roof from below. Try to imagine yourself standing before the building. Draw the nearest corner, then if the roof line is above your eye level it will appear to run downhill away from you and the ground line will appear to run uphill. If you are drawing on site hold your pencil horizontally in front of one eye, against the building as it were – shut the other, and you will be able to see the correct angle very easily. If you are looking straight on at a building, the top and bottom lines will be parallel with the top and bottom of your page.

MOUNTAIN AND LOCH,

watercolour on thick cartridge paper, 15 × 23 cm (6 × 9 in)

The mountains were painted in increasingly stronger washes of Indigo. The darker areas appear to advance and the lighter areas to recede. Strong tonal contrasts bring the boat and the people ‘forward’ to give depth.

AERIAL PERSPECTIVE

Aerial perspective means that tones and colours will become fainter in the background. We all know about the ‘blueing’ effect in distant hills where sky and land become almost indistinguishable.

TONE

Try painting a picture using one colour. Allow the nearer tones to become stronger by building up one wash on top of another and you will create depth. Strong tonal contrasts in foreground details will develop it further.

OVERLAPPING

If you draw objects separately across the picture surface, you will struggle to create the effect of depth. On the other hand, if you allow some objects to overlap others you will immediately suggest their spatial positions. Make the ones in front bigger and more tonally developed and depth will be reinforced.

WEIGHT OF LINE

Dark, strong lines drawn against a light background will advance into the foreground. So vary your linear quality to exploit this effect in drawings or paintings. It is really the converse of how white chalk works on a blackboard. The contrast between black and white makes the chalk legible, but try using white chalk on white paper and it becomes difficult to see.

Little exercises like these, using overlapping and tonal contrast can be done quickly. It is possible to create all kinds of depth effects using these elements. Invent your own wonderful landscapes and worlds by playing about with viewpoints and eye levels.

HARBOUR WALL

watercolour, pen and ink, 63 × 44 cm (25 × 17 in)

Linear perspective was used in the drawing of the houses and the boat’s cabin. Notice that because the house tops are above us the roof lines slope down into the distance and we cannot see the top surfaces of the chimney supports. Aerial perspective has been suggested by using lighter tones and gentler contrasts in the background, saving the stronger effects for the middle and foregrounds. Overlapping was used extensively.

TEXTURE

Texture is a quality that can be so easily overlooked in painting. Try to develop your skill with it. Perhaps you could use thin washy paint layers in the background and thicker textural layers in the foreground. This is easier in oils or acrylics, but you can create varied textures in watercolours as well, by using dry brush, for example. Do not try using watercolour straight from the tube, however; it may crack as it dries. Respect your medium and work within its limitations.

Take one landscape or still-life subject and work it out in several versions using different depth techniques in each. Then try a combination of methods, in different proportions, to see which is most effective. These do not have to be ‘finished’ pieces; after all, you are hoping to learn from them. Quick, small studies are ideal.

Depth is something most of us try to achieve in our work. By experimenting with these techniques and exercises your skill will increase and your paintings improve.

4

SEVEN-MINUTE SKIES

Is there a quick and simple method of painting a sky in watercolour?

Answered by: Winston Oh

Have we not all had the experience of drawing a good landscape complete with fine architectural detail and then wrecking it immediately by messing up the sky? In order to succeed, it is important to pay attention to details such as your brush, paper, amount of water, paint, and speed of application.

Think of the sky as a loosening-up exercise. It is the least demanding component of your landscape. Unlike a building or other physical structures, you are not expected to paint the exact sky before you. Instead, you have the freedom to create the sky of your choice to suit the overall composition or the atmosphere you have chosen to depict.

Using the wet-on-wet technique is preferable because it results in a soft effect in cool colours, without hard edges, naturally contrasting with the stronger landscape tones and putting the clouds in the far distance where they belong.

INITIAL PREPARATION

For a support choose 200 gsm (140 lb) paper or more, as heavier weights do not cockle during the wet-on-wet exercise. A Rough or Not surface provides absorbency, which helps to produce soft fluffy clouds. A rougher surface makes it easier to leave random, irregular white unpainted accents on cloud edges, and facilitates the attractive flocculent textured effect of French Ultramarine when it dries.

BERNEY ARMS WINDMILL, NORFOLK

watercolour, 30 × 46 cm (12 × 18 in)

A grey, windy day, with low scudding clouds, enlivened by streaks of white paper showing through. This was painted with a large squirrel hair brush, in swift horizontal strokes, using various mixes of French Ultramarine and Burnt Umber. Payne’s Grey was used for the heavy rain cloud. Th distant trees were painted with a mix of French Ultramarine and Indian Red.

Your brush has to be large enough to hold sufficient water. For a picture about 30 × 45 cm (12 × 18 in) use a large squirrel hair brush, or a size 10 or 12 sable. On a picture 25 × 35 cm (10 × 14 in) use a size 9 or 10 brush.

Step 1 shows a soft grey sky, achieved with wet-on-wet technique.

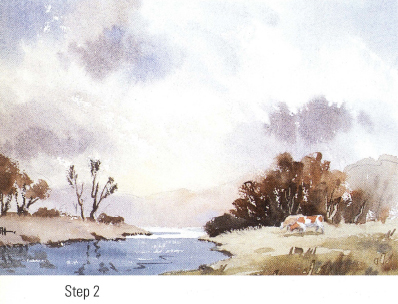

In Step 2 brisker brushstrokes are added to produce a cloudy sky that is fresh and lively.

For the purposes of the two demonstration pictures of a cloudy sky above, I used a combination of French Ultramarine and Burnt Umber predominantly. My other usual colours are Cobalt Blue, Coeruleum, Light Red and Raw Sienna. A blue sky may gradate from Ultramarine to Cobalt Blue to Coeruleum towards the horizon as a result of refraction through the atmosphere. Often there is a warm glow just above the horizon, for which I use dilute Raw Sienna. Light Red is mixed with French Ultramarine or Cobalt Blue to create a cooler grey for distant clouds that are near the horizon.

Roughly plan where your cloud or clouds and darker tones are going to be placed, in relation to the rest of your composition. Indicate lightly with pencil the shape or rough outline of the cloud pattern. After gaining experience with this sky technique, it can be fun to improvise cloud formations without prior drawing.

THE WET-ON-WET METHOD

To start, angle the painting surface at 10 or 20 degrees. Wet the sky area fairly liberally and briskly with sweeping strokes. On rough surfaces this action will leave a few random irregular dry spots for accents. Unwanted spots can be covered over in the next stage. Leave larger dry irregular areas if you wish to create a prominent white cloud edge. Of course, you could wet the whole surface evenly for a soft fluffy cloud effect, as in Step 1.

Charge the brush with a moderate amount of a mixture of French Ultramarine and Burnt Umber of moderate intensity. More of one or other colour will determine how grey or bright a day you wish to portray. This is the base layer, so lay it on loosely in broad, preferably oblique, strokes, starting in one top corner. I use this as my tester corner. If the first stroke is too light, I can then stiffen the mixture immediately. I like a fairly strong toned corner anyway. As you move away from the corner, lighten the tone, varying the mixture with each brushload. If one corner is grey, make the other corner bluer. Where you wish to have white clouds, leave a gap of 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in) to allow for some diffusion of colour from the wet edges. Work your way down the sky, and by the bottom third dilute the grey towards the horizon, leaving it almost white around the middle third of the horizon.

Proceed immediately to the next stage (Step 2), where it gets more enjoyable. Use a significantly stiffer mixture of the same colours, with less water. This is important, because anything more dilute will make a mess and ‘cauliflowers’ may appear. Use this to darken clouds. As you move down the sky, narrow down the height of the clouds as they recede towards the horizon. Use Light Red mixed with French Ultramarine for the lower distant clouds with cooler tones. Do not forget to vary the size of the clouds.

Then, while the surface is still quite wet, you are ready for the final accents. Fill the tip of the brush with strong pure French Ultramarine and drop this into one or two small areas among the grey clouds to suggest blue sky peeping through. If you place the spot of blue beside a white cloud, it will accentuate the white edge immensely. Try washing in a dash of dilute Raw Sienna at the mid-horizon, behind a mountain or a pale area within a white cloud. You will be surprised at how this lifts the colour in the sky.

Now stop! Lay the painting flat and let it dry. Do not rework any part of the sky before it is completely dry. There is a cut-off point when the paper is about two-thirds dry, beyond which any application of paint will spoil it. Some accentuation can be done after drying. Wet the area first with clean water, and then drop in a darker, stiffer paint lightly. This exercise should take you no more than ten minutes. I call it the ‘seven-minute sky’ simply to emphasize the key element of the technique – its swift application. A loosely painted, fresh-looking sky only works well while the surface of the paper remains fairly wet.

LOW TIDE AT PIN MILL, SUFFOLK

watercolour, 30 × 46 cm (12 × 18 in)

A sharp white cloud edge was obtained by keeping the upper cloud border dry while wetting the rest of the sky area. The contour was further shaped while working in a stiff wash of French Ultramarine. Light Red was mixed in for more interest in the sky.

When the sky is dry, you will notice that the colours are about 10 or 25 per cent lighter. This may disappoint initially, but when the whole picture is completed, you will appreciate that the lighter sky contrasts well with the landscape below, and it recedes into the distance where it belongs. Practise and experiment with different colours and tones, and you will develop your own version of the seven-minute (more or less) sky!

5

THE LONGER VIEW

I always have problems with my foregrounds. Can you offer some help on how to tackle them successfully?

Answered by: Jackie Simmonds

Foregrounds can cause all sorts of problems. Too much detail, and the viewer’s eye is held firmly in the foreground and fails to explore the rest of the picture. Too little attention to the foreground, however, may result in a boring, unconsidered area at the base of the picture. Often the main problem is that the student has not taken on board the idea that the foreground area of a painting has a purpose, and that purpose is usually – although there are no hard and fast rules in painting – to lead the viewer’s eye into the scene. Even in the shallow space of a still life, or an intimate corner of a landscape, the foreground of the picture needs to be carefully considered.

CAPE TRAFALGAR FISHERMEN

pastel on pastelcard, 46 × 66 cm (18 × 26 in)

I placed the horizon high in the rectangle to leave plenty of space for the foreground. In this way I was able to use the wave tops and edges, and the edge of wet sand, to draw the eye firmly towards the fishermen. A large foreground emphasized the emptiness of the beach, bar a few fishermen, and gave me the opportunity to paint the wonderful light on the sea, which was as important an element as any other in the picture.

ORGANIZING THE DIVISION OF SPACE

Before launching hell for leather into a painting, one of the best ways to prevent the foreground causing problems is to do a thumbnail sketch or two. I have lost count of the number of times I must have mentioned this, so forgive me if you are one of those who hates thumbnail sketches, and is fed up with being told that they are important. However, a small thumbnail sketch, executed in a few minutes, will quickly show you if your divisions of the rectangle are uncomfortable. You will be able to decide, before committing yourself to colour (and in watercolour painting, this is an extremely useful plus point), whether you have left too much or too little space for the foreground. You can change elements of the scene, in order to direct the eye more positively to the main centre of interest. You can decide whether you want foreground elements to dominate your picture – or whether they need to be drastically subdued. Making fundamental changes of this sort once a picture is well under way is not conducive to good temper!