Полная версия

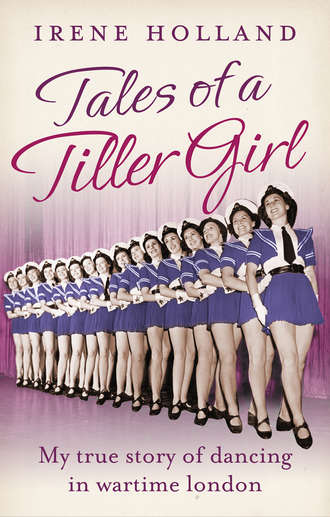

Tales of a Tiller Girl

‘Poor Uncle Harry,’ she said. ‘The bomb went off straight in his face.’

‘Is he all right, Mum?’ I asked.

‘Oh yes,’ she said. ‘It gave him a bit of a fright and singed all his eyebrows off, but apart from that he’s fine.’

Even though it was mean, we couldn’t help but have a bit of a chuckle about it.

The war also brought me a new playmate. I became best friends with a pretty little blonde girl called Diana Baracnik, whose family moved into our street after fleeing from Czechoslovakia. We’d climb trees or go to dance classes together, and after school I’d go round to her house and play dollies. I loved my dolls and I had about six of them. Some of them were china and some were papier mâché.

One person who felt very strongly about the war was my brother Raymond. He’d always been a socialist like my father and he shared his strong views.

‘Wars and violence don’t solve anything, Rene,’ he told me. ‘Nobody wins in war.’

He didn’t want any part of it and he was one of those known as conscientious objectors – people who for social or religious reasons refused to go to war.

During the First World War conscientious objectors were seen as criminals and sent to prison. Women would wander round and hand any man who was the right age and not wearing a military uniform a white chicken feather, which was a symbol of cowardice, to shame them into enlisting. Several conscientious objectors killed themselves because they couldn’t cope with the stigma. During the Second World War the punishment wasn’t as severe, but you could still be arrested for refusing to do National Service and you had to appear in front of a tribunal to explain your reasons why. Despite the risks, Mum respected Raymond’s opinion as she shared similar beliefs.

‘Your father would have been so proud of Raymond,’ she told me. ‘I know he would have done exactly the same if he was here now.’

Mum had told me many times that my father was strongly anti-war. Because of his bad asthma he wasn’t called up during the First World War, but his older brother Raymond had been.

‘Raymond was a tail gunner, and the first time he went up he was shot and killed instantly,’ said Mum. ‘Your father was heartbroken. He said his poor brother was just cannon fodder and that only reinforced his anti-war stance.’

It seemed apt that my brother had been named after our late Uncle Raymond.

One morning we were all having our breakfast when there was a loud rap on the front door.

‘Open up,’ shouted a gruff voice. ‘It’s the police.’

Mum looked at Raymond in a panic. I didn’t have a clue what was going on.

‘What shall I do?’ she whispered to him.

‘You’d better go and let them in,’ he said. ‘I’ve got nothing to hide.’

Mum went and opened the door, and two officers came marching up the stairs and into our dining room.

‘Raymond Bott?’ one of them said to my brother.

‘Yes,’ he replied.

‘Young man, I’m afraid we’re going to have to arrest you for failing to register for National Service,’ he said, pulling him up from his chair. ‘Come with us, please.’

‘I’m a conscientious objector,’ he told them. ‘I don’t believe in war.’

‘Well, you will have to appear in front of a tribunal and tell them your reasons for that. Then they will decide what will happen to you,’ the other one said.

Mum burst into tears.

‘You can’t do this,’ she sobbed. ‘You can’t just take him away like this.’

‘I’m afraid we have to,’ one of them said, leading him off down the stairs. ‘We’re just obeying orders.’

My brother didn’t say a word, and he wasn’t allowed to take anything with him. My mother was inconsolable, and I could hear Miss Higgins frantically ringing her bell downstairs, probably trying to find out what all the fuss was about.

I just sat there eating my toast, completely stunned by this drama that was happening over breakfast.

Mum followed the officers downstairs, and I ran to the window and watched as they pushed Raymond into the back of the police car and drove away. A few neighbours had come out of their houses to see what was going on too, and they all stood there staring. Mum came upstairs sobbing.

‘I can’t believe this has happened,’ she cried.

The following evening after school I called at my friend Diana’s house as usual. Her father answered the door.

‘I’m sorry, Irene,’ he said. ‘You won’t be able to play with Diana any more or come round to our house.’

‘But why?’ I asked. ‘She’s my best friend.’

‘You’d better ask your mother,’ he told me.

I went home in floods of tears to Mum.

‘Diana’s dad says I’m not allowed to be her friend any more,’ I sobbed. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘He probably heard about what happened to Raymond,’ she said. ‘A lot of people don’t agree with your brother’s views about the war.’

‘But what do you mean?’ I asked. ‘What’s that got to do with Diana’s dad?’

‘He probably thinks that Raymond’s a coward for not wanting to fight the Nazis,’ she explained. ‘Perhaps his family had a bad time in their country, which is why they came over here.’

I was devastated that I’d lost my best friend. I couldn’t understand what difference the war and my brother’s beliefs made to whom I could and couldn’t play with.

But it wasn’t just a one-off. Word soon spread among our neighbours that Raymond had been taken off by the police, and after that a lot of people wouldn’t talk to Mum or me. They’d see us in the street, put their head down and walk straight past us. There was a huge stigma attached to being a conscientious objector, or a ‘conchie’ as they were nicknamed. A lot of people associated it with being a coward, but in fact most conscientious objectors were motivated by religious reasons.

Raymond had to appear in front of a tribunal that would decide whether to give him an exemption, dismiss his application and send him to fight, or make him do non-combatant work. A week later we received a letter from him.

The tribunal decided that I should be sent to work in the Pioneer Corps where they have given me the task of digging up roads. It’s hard labour and the days are long but at least I have stuck to my principles and I’m not involved in any way with the taking of lives. I’m stationed at a barracks in Lincolnshire and ironically most of my fellow conscientious objectors are extremely religious so they are slightly bemused at being billeted with an atheist like me who is constantly questioning their beliefs.

Mum was relieved that he was all right, although she was annoyed by the type of work Raymond was doing.

‘What a waste of his talents,’ she sighed. ‘He’s far too clever to be digging up roads.’

His superiors must have realised that too, as soon Raymond wrote to us again to say that he had been transferred to the Army Service Corps, where he was given the job of drawing maps. Part of his role eventually involved helping to plan the D-Day landings, which he justified by saying it was about saving lives rather than taking them.

Despite the war, daily life at home went on as normally as possible. By the time I was ten, however, Mum had run out of patience with Miss Higgins.

‘I can’t look after that woman for a second longer or I swear I will kill her,’ she told me.

But work in the orchestras was in short supply during the war as some theatres had been badly bombed and were forced to close. Things were going to be tight financially again, so we were forced to move back in with my grandparents.

The day before we left the house in Norbury, a government inspector came out to check all the Anderson shelters in the street. Mum and I watched as he tapped the mortar between the bricks. To our horror, it crumbled instantly and his finger went straight through it.

‘Shoddy workmanship,’ he sighed, shaking his head. ‘If a bomb had dropped on that thing it would have been curtains for you two.’

Mum and I stared at each other in shock.

‘I don’t believe it,’ she said. ‘To think we’ve been sleeping in there every night for nearly two years thinking that we were safe.’

By this time my grandparents had rented out their attic room to a ninety-year-old spinster called Miss Smythe, so Mum and I had to live on the much bigger and lighter second floor of the house. It felt like a palace compared with the poky, cramped attic. We had two bedrooms, and our own living-room and bathroom. Moving back to Battersea meant that I had to change schools to Honeywell Road Primary, but I still did my ballet lessons, which I absolutely loved.

One day Mum sat me down.

‘What you want to do when you grow up, Rene?’ she asked.

I knew my answer straight away, because since I was a little girl I’d only ever wanted to do one thing.

‘I want to be a ballet dancer,’ I said. ‘I want to be on the stage.’

A lot of other parents at that time might have just laughed or told me I would have to go out and get a proper job, be a teacher or a secretary, but Mum didn’t flinch.

‘All right, then,’ she said. ‘You’ll have to go to stage school if you’re really serious about doing that. Where would you like to go?’

‘Italia Conti,’ I said without hesitation.

It was the world’s oldest and most prestigious theatre arts training school, the one that the older girls at dance class always talked about. I didn’t ever think in a million years that Mum would be able to afford to send me to stage school, but to my surprise she didn’t question it.

‘Very well,’ she said. ‘I’ll contact Italia Conti and get some more information.’

Mum kept her promise and a few days later she told me what they had said.

‘It’s £20 a term,’ she told me.

My heart sank. That was a heck of a lot of money in those days, and I knew it was the end of my big dream. As a single mother who went from one job to the next as a violinist, there was no way she could afford expensive stage-school fees like that.

But in 1942 Mum made the biggest sacrifice of her life for me. She sat me down one day and took hold of my hands.

‘There’s something I need to tell you, Rene,’ she said. ‘I think I’ve found a solution to our problems. I’ve decided to join ENSA.’

ENSA stood for the Entertainments National Service Association, a group of performers who travelled around the world during the Second World War to entertain British troops and keep up morale. They had everything from singers, dancers and musicians to comedians, bird impersonators, contortionists and even roller skaters.

‘The pay is good, and having a regular wage is the only way that I can afford to put you through stage school,’ she said. ‘It means that I’ll be away from home for a while, but you can stay here with Papa and Gaga. They’re going to post me to Egypt, where I’ll perform as part of a quartet.’

It was a huge shock, and I couldn’t believe she was prepared to do that to help me achieve my dream.

Things moved so quickly. A week later I sat on my mother’s bed watching her put on her new ENSA uniform, which consisted of a khaki shirt and belted jacket, an A-line skirt with a pleat up the middle, and a peaked hat. It hadn’t really sunk in yet that she was going thousands of miles away and I wouldn’t see her for years.

‘Come on, then,’ she said, holding out one hand to me while in the other one she clutched her beloved violin. ‘It’s time to go.’

We caught the Tube to the Coliseum, the theatre from where the new recruits were departing. As we walked towards the entrance I could see a big fleet of three-tiered coaches waiting outside. It was pandemonium as hundreds of performers in ENSA uniforms said tearful goodbyes to their families. Mum handed someone her violin to load into the bottom section that was filled with an array of musical instruments. Then she turned to me and gave me a cuddle and a kiss.

‘Oh, Rene, I really don’t want to leave you,’ she said, tears welling up in her eyes.

‘Oh, don’t worry, I’ll be all right,’ I said, as I hated to see her upset.

‘I love you very much,’ she told me.

Then she turned and walked away. I could see her dabbing her eyes with her hankie as she climbed onto the coach. I watched her take her jacket off, and as she sat down and waved to me through the window that’s when it finally hit me.

This was really happening. She was really going.

The only person in the world besides my brother that I loved with all my heart was leaving me.

I was in such a state of shock I couldn’t even cry.

As I watched her coach drive away I felt completely and utterly alone in the world.

I got the Tube home in a daze. I was used to being on my own and I was fiercely independent, but it felt very frightening at the age of twelve not having anyone looking out for me. With Mum and Raymond both away, there was literally nobody in my life that I could go to. No one to give me a kiss or a cuddle, or who would make sure that I was all right and put me first in the world. My grandparents weren’t interested, that was for sure.

When I got in that evening they didn’t ask me anything about Mum or whether she had got off OK or if I was all right. But as I walked through the door I couldn’t hold back my emotion any longer and I burst into tears.

‘Whatever’s the matter?’ my grandmother asked.

‘I’m just really sad about Mum going away,’ I sobbed.

‘Oh, don’t be so selfish,’ she said.

I knew that was the way it was going to be and I just had to get used to it. Nobody was going to say what I so desperately wanted to hear right now, things like ‘Oh, come here and give me a cuddle, Rene, I know you’re missing Mummy. Sit down and let’s write to her together.’

Nope, I was by myself now. Raymond was still in his barracks up north and Mum was on her way to Africa.

That night it was hard going to sleep on my own. For all of my life I’d had Mum there beside me, but I knew I had to pull myself together and get on with it.

She had done this for me because she wanted me to achieve my dream of going to performing arts school. I had an interview with Italia Conti coming up, and I knew that I had to pass it. I had to get in. For Mum’s sake and for mine.

4

Fairyland

Walking towards the heavy black door, I swallowed the lump in my throat. Today was the day that I’d been waiting for. It was my audition at Italia Conti, the country’s most prestigious theatre arts school.

As usual I was here on my own. My grandparents hadn’t said a word when I’d told them about the audition. No ‘Good luck, dear’ or ‘I hope it goes well.’ Not that I’d expected them to say anything or take any interest in what I was doing, as I knew by now that wasn’t going to happen. I knew that it was down to me to do this. Mum had sacrificed everything and gone away so that I could achieve my dream, and I had to get in.

My tummy was churning with a strange mixture of nerves and excitement as I walked up to the front door of Tavistock Little Theatre in Tavistock Square where the school was based. It was an old Victorian building and nothing fancy, but as soon as I pushed open that black door I entered a hive of activity.

Like a Tardis, it opened up inside to reveal several huge rehearsal rooms. There were girls running past in their black dance tunic uniforms, and every time a door opened I could hear the faint tinkle of a piano, the clatter of tap shoes or someone singing scales. I instantly felt at home and I knew this was where I wanted to be, singing and dancing all day long.

I stopped one of the girls going past.

‘Hello, I’m here for an audition,’ I told her, thankful that I hadn’t stammered.

‘I’ll go and get Miss Conti for you,’ she said.

A few minutes later one of the doors opened and a middle-aged lady with short, dark hair came out.

‘Hello, I’m Rene … I mean Irene Bott,’ I said. ‘I’m here for an audition.’

‘Wonderful to meet you, Irene,’ she said. ‘I’m Ruth Conti, Italia’s niece.’

Before she left, Mum had told me that Italia Conti, or old Mrs Conti as everyone called her, was still around but she was in her seventies now and so her niece Ruth had come over from Australia to help run the school.

‘You’ll have to excuse us,’ she said. ‘Our old school in Lamb Conduit Street was bombed out by the Germans last year, so the theatre have kindly lent us their rehearsal rooms until we can find some new premises.’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘I hope no one was hurt.’

She shook her head.

‘Thankfully all of the staff and pupils were on tour at the time with one of our shows. It was our poor building that took the brunt of the Nazis but we’re managing to muddle through.

‘I see you’ve bought your dance bag,’ she said. ‘Get yourself changed and then you can join in a ballet class first.’

‘Thank you, Miss Conti,’ I said.

Even though she seemed friendly, I could tell by the steely look in her eyes that she wouldn’t take any nonsense. As I got dressed into my dance tunic I started to feel very nervous and overwhelmed.

You can do this, Rene, I told myself.

I followed Miss Conti into an old, draughty rehearsal room, where lots of girls and a few boys were waiting. There was a ballet barre running down one side and big mirrors. The windows were all blacked out because of the war, so the room was lit by dim electric light. Miss Conti led me over to the front of the room where two women were talking. One was very tall and masculine looking. She had bobbed straight hair and was wearing trousers, and I couldn’t help but notice the big stick in her hand.

‘Hello, dear,’ she said. ‘Come in and join us. Have you done much ballet before?’

‘I’ve been going to classes since I was four,’ I said.

The other teacher couldn’t have been more different. She was small and feminine and had her hair pulled up in a bun, a floaty skirt on and a face full of make-up.

‘I’m Toni Shanley,’ said the tall, fearsome lady. ‘And this is my sister Moira Shanley.

‘Take your place and let’s begin. Just do what you can.’

‘Yes, Miss Toni,’ I said.

A grey-haired lady in a flowery dress was sitting at a piano in the corner with a cigarette hanging out of her mouth. Miss Toni gave her a nod and she starting playing, puffing away on her cigarette with a bored look on her face.

‘Ready, girls,’ said Miss Toni. ‘Heads up, straight backs.’

As we stretched, she walked down the length of the barre correcting people by giving them a sharp rap with her stick.

‘Bottoms in, shoulders down,’ she yelled, coming down the row towards me.

‘Chin up, chest up,’ she said, lifting up my head with her finger and pressing in my rib cage. ‘Carry on, dear.’

I was nervous, as I knew both Miss Shanleys were watching me closely, but I was also very determined. I managed to follow every step and carry on until the end, but I didn’t have a clue how it had gone.

‘Well done, Irene,’ said Miss Moira after class. ‘You’re a good little dancer. I think Miss Ruth wants you to go to drama and elocution now.’

She seemed very sweet and gentle compared with her fearsome sister.

I hoped it had gone well but I was terrified that I wasn’t good enough. I knew I could do ballet, but I’d only been to my little local class and I’d only briefly had a few tap lessons.

If Miss Toni was scary, the drama teacher was the most terrifying woman that I’d ever seen in my life. She was wearing a long fur coat that dragged on the ground behind her and a huge Russian fur hat.

‘Don’t mind Miss Margaret,’ one of the boys whispered to me. ‘She’s a bit of a dragon.’

‘I can see that,’ I said.

She was very theatrical and what people might call a bit of a ‘luvvie’.

‘Come in, de-arr,’ she said in a big, booming voice when she saw me lurking by the door. ‘I’d like you to recite some Shakespeare for the class today.’

My heart started to pound with nerves.

‘Up on the stage?’ I said. ‘In front of everyone?’

‘Yes, de-arr,’ she said. ‘Is that a problem?

‘N-no,’ I said.

I didn’t normally get nervous but suddenly I was the most frightened that I’d ever been in my life. It wasn’t the fact that I’d never done drama before that was bothering me; it was my stutter that I was worried about. Would they give me a place at stage school if they knew that I stammered?

My legs felt like jelly as I stood on the stage and Miss Margaret passed me the play. It was one of Macbeth’s well-known speeches.

The whole room was deadly silent and all eyes were on me. My hands were shaking as I scanned the words.

Is this a dagger which I see before me?

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

You can do this, Rene, I told myself.

I took a deep breath.

‘I-is th-this a d-d-d- …’

B’s and d’s were particularly tricky for me to say, and no matter how hard I tried, the words just wouldn’t come out. I completely panicked and started gasping for breath.

I seemed to be up there for ever, but finally Miss Margaret waved her hand to stop me.

‘I see you have a stammer, dear,’ she boomed.

‘Y-yes,’ I said, ashamed and completely mortified that I’d shown myself up in front of the whole class

‘Let’s leave it there, then,’ she said.

I felt sick afterwards. She didn’t say anything else, but I was so worried that I had blown my chances.

Next up was a tap class, where the teacher was a tiny woman with jet-black hair and bright red lipstick. I much preferred ballet to tap, but I’d done a little bit before and managed to follow all the steps.

At the end of the morning, Miss Conti called me in to see her.

‘Well, Irene, I’ve had a chat to the teachers,’ she said.

I could feel my heart thumping out of my chest. I didn’t know what I’d do if they didn’t want me. How would I tell Mum that I’d failed?

‘By all reports you’re a lovely little dancer,’ she said. ‘A few other areas need a bit of work but we’ll take you.’

‘Pardon?’ I gasped. ‘Really?’

‘Yes, dear,’ she smiled. ‘I’ll give you a list of what you’ll need to bring with you to class. You can start next week.’

I couldn’t believe it, I was on cloud nine. I’m going to be a dancer, I thought, triumphantly. I’d done it! I couldn’t wait to write to Mum and tell her the news when I had an address for her. It really was a dream come true. I was going to spend every day doing what I loved and was so passionate about.

‘Gaga, Papa, I got into Italia Conti!’ I told them excitedly when I got home.

‘Very good, Rene,’ said my grandmother, not even bothering to look up from her needlework. I didn’t expect to get glowing accolades, but it would have been nice for them to acknowledge it. After all, they always seemed so proud of their other grandchildren who were all very academic and had gone off to good schools and universities.

The only downside of starting at Italia Conti was that I would have to leave Honeywell Road Primary, where I was very happy. I had a wonderful teacher there called Mrs Ritchie, and I couldn’t wait to tell her my news.

‘Mrs Ritchie, I got into Italia Conti,’ I told her with a big grin. ‘I start next week.’

‘Well, that is excellent news,’ she said.

At the end of the day, she called me over to her and pulled out a chair from under the table.

‘Stand up there, Rene,’ she said in a loud voice. ‘Now tell the rest of the class what you’re going to be.’

‘I’m going to stage school and I’m going to be a ballet dancer,’ I said proudly.

The whole class clapped and gave me three cheers. She was the only person to recognise my achievement and it felt lovely to have someone making a fuss of me. It made me feel really special and I’ve never forgotten that.

Even though I was sad to leave school I couldn’t wait to start at Italia Conti. I spent the next week getting all of the things that I needed for class. Thankfully Mum had left me some money for any extras that I might need. My grandmother made my uniform, which was a black sleeveless satin tunic with two slits up the side and tied in a bow at the back, and black cotton gym knickers.