Полная версия

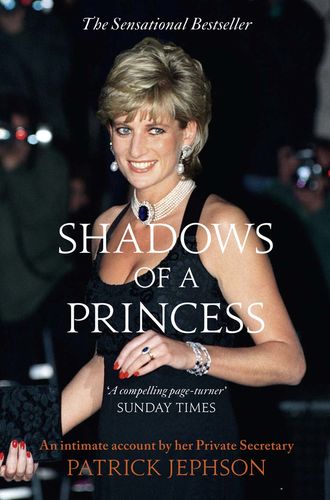

Shadows of a Princess

Ultimately she lost touch with reality in her restless desire for reassurance. In the last year of her life she was quoted in Le Monde as saying, ‘I don’t need to take advice from anyone. I trust my own instincts.’

The truth was, she consumed advice insatiably and, depending on her mood, she would take it from anyone. Her credulity seemed directly proportional to the thrill factor of whatever prediction she was being invited to believe – which made her pretty much like the rest of us, I reluctantly concluded.

Even so, I thought it important to affect a cheerful cynicism about every latest fad. My light-hearted attitude was intended to acknowledge the need for attention without conceding that she was anything other than physically fit as a fiddle. I never knew her to be genuinely ill for a single day. She kept her side of the pact by allowing – and maybe even welcoming – my theatrical disapproval as she swallowed the latest offerings from her army of alternative practitioners. As a reassuring contrast, I extolled the more traditional merits of hot whisky and a good book as aids to happy slumber. Perhaps sensibly, however, she avoided alcohol.

The real problem was that she had no safe substitute for the wise, supportive and unpaid company which, in the end, was the only medicine she really needed. Underneath the light-heartedness I was worried about her growing tendency to find pseudo-medical excuses for attracting attention and sympathy. She became increasingly indiscriminate in her search for physical remedies for emotional disorders. Complementary cures were freely interspersed with more conventional sleeping pills and stimulants.

The effect of these combinations was anybody’s guess, since no single doctor knew what she was dosing herself with, let alone controlled her intake. Deep-tissue massage and painful vitamin injections also became regular features of pre-tour preparations. Once, in a fit of hypochondria, she wangled an urgent MRI scan. Unsurprisingly, the scan confirmed my own less penetrating diagnosis: she was as fit as a fiddle.

Reassurances and remedies were all to little effect in lonely hotels and guest residences, however. All the pills in the world did not seem able to help then, and she fell back into less esoteric habits. Too often, time spent in her room supposedly relaxing was spent in obsessive phone calls – gossip with girlfriends; gossip and flirting with admirers; gossip and intrigue with palace staff back home; and, on the plus side, laughter and light relief with her children, whom she missed acutely whenever she was abroad without them.

Nothing she took seemed to dull her quick-wittedness, or her quick tongue. Depending on her mood, I found that she could be perceptive and thoughtful with her praise and encouragement, if a little inconsistent. Getting a pat on the back one day did not protect you from being kicked the day after for doing the same thing.

When she was unhappy, her natural suspicion and deviousness took control. Then her verbal skills were employed to hurt and confuse. When roused, she used words like tomahawks and her aim seldom failed. She would know, with a cat’s cunning, when to let you feel the claw in her velvet paw. Like the predator she sometimes was, she would stalk her victim, waiting for his or her attention to be distracted before striking.

Typically, we might be on a train about to arrive at our destination and my mind would be preoccupied with the practical demands of the next few minutes, when she would see her opportunity. Her voice would take on that tone of guileless inconsequentiality that always made the hairs stand up on the back of my neck.

‘Patrick, you never told me I’d been invited to speak at the Sprained Wrist Association AGM. I know you wouldn’t understand, but people with sprained wrists are excluded by society. I think we ought to make a speech about it.’

The opening volley was designed to saturate my defences. While still distractedly craning out of the window for a telltale sign of red carpet and a press posse, I would subconsciously assess the incoming missiles:

- She has deliberately chosen a bad moment for me. This kind of premeditation always spells trouble. Look out for the second salvo. (My God, I hope she doesn’t know about that business with her new car…)

- She is accusing me of deliberately concealing an invitation from her because I disapprove of it or because I am too lazy to research it. (Both true on occasions, as she probably knows.)

- Why the Sprained Wrist Association, for goodness’ sake? Aha – cherchez a handsome radial osteopath. Extra trouble: she loves to pretend you are jealous.

- Note that I am too insensitive to understand. This means I have missed a recent opportunity to be sympathetic, exacerbated by the fact that, unlike herself and people living with SWS (Sprained Wrist Syndrome), I have no idea what it is like to feel rejected.

- And now ‘we’ have to make a speech. This means a heap of exploratory work with the Department of Health (again) and probably a ruined weekend while I draft the speech (again). The speech will then be rejected because take your pick – she has gone off the osteopath/the Daily Mail says SWS is all in the mind/the astrologer forbids speeches during the current transit of Pluto/the Prince is patron of the Sprained Knee Association and we are making a show of not competing at the moment.

- Worst of all, somebody has snitched on me. How else did she find out about the invitation? Surely not one of the girls in the office … somebody looking through my papers … maybe the butler … the driver … Oh no! So she must know about—

‘Patrick! And when were you going to tell me you’d ruined my new car?’ [CURTAIN]

Of course it helped, always having the last word.

As time passed and I travelled with her more and more, I observed a phenomenon more usually associated with declining politicians and rock stars. The Princess found foreign tours stressful, both physically and mentally, yet she needed the buzz only they could provide. Tours also put her under unusually intense press scrutiny, because the travelling pack had no distractions other than her and the hotel bar, yet she delighted in the unmatched range of exotic and heart-tugging photo opportunities they provided. This persisted even when, as sometimes happened, the resulting press coverage back home was infuriatingly inaccurate and slanted.

When I challenged one of the travelling correspondents with a particularly misleading front-page story bearing his by-line, he genuinely seemed to share my outrage. ‘It’s the editors,’ he protested. ‘They rewrite my stuff to conform with their current line on the War of the Waleses.’

This last remark came back to me later. The Princess’s relations with the media were becoming a subject of growing interest to me, and to the public at large. I had already noticed that both she and her media pursuers had almost made a game out of satisfying their mutual requirement for each other (with truth as the first piece to leave the board), even though at times she would show flashes of resentment at press attention.

It was also dawning on me that there was something in her character which was attracted to this love-hate relationship. It was echoed elsewhere in her life. I often saw it in her attitude to her husband, or his family, or the public duties she did so well, and on each occasion it was the love half of the equation that seemed hardest for her to feel. Time and again, like an untrusting child, she doubted the dependability of the love she was shown. Small wonder, then, that she protected any affection she felt able to give – except to her children – with a portcullis of preconditions.

On a day-to-day basis, our job was to design her programme in such a way that the press had the best possible chance to report her routine public duties favourably, without inconveniencing the organizations she was visiting. If those organizations benefited in the process – and some did in spectacular fashion – then so much the better. On a deeper level, however, a dangerous mutual dependence was certainly growing. The media stimulated the Princess’s appetite for attention, but never satisfied her true requirement for love and security.

This produced some confusing results. You might not readily associate media phobia with the star of Panorama, but it became a daily reality for me. A distressed Princess is famously remembered to have asked, ‘What have the tabloids ever done for me?’ To this plaintively rhetorical question tabloid editors gave rather less rhetorical replies along the lines of, ‘We made you, darlin’!’ And so, in a sense, they had.

Unfortunately, it was not in a sense that gave her any feeling of genuine worth. After all, if being ‘made’ is to have a life as thin as the paper it is printed on, it might make you doubt your very existence. I came to think that the media were a kind of family to her. Theirs was the language of a desensitized childhood – extravagant praise followed by harsh rebuke. Like a child coaxed on to its parent’s lap for comfort, the pain of then being pushed carelessly aside was all the greater for her.

Although I only dimly understood the reasons for the Princess’s childlike temperament, I knew they were deep and traumatic. They left her constantly in need of reassurance. Tragically, she cared less and less whether this reassurance was healthy, or where she found it. For her, words of comfort were even more essential than for the rest of us.

It was one reason why she was so good at dispensing them herself. How often her messages of kindness and encouragement must have seemed a mirror of those she would have liked to receive. Perhaps the most poignant difference was that from her the words were as genuine as she could make them, but those she received were avidly gathered up like flowers on a walkabout, unconditionally and indiscriminately. The words were what mattered, and she cared little whether they had been truly meant, or whether they came from policeman or President, butcher or baker, butler or playboy.

For me, however, especially in those early years, it was enough to know that she had to be jollied along with flattery, humour, gift-wrapped advice and very visible loyalty – especially from men. I had only to master the formula, combined with an alert sense of self-preservation, to see out my brief appointment successfully.

Another thing I noticed about the Princess as my apprenticeship came to an end was her tendency very vocally to dread overseas tours but then, as soon as one was over, to look forward eagerly to the next. Given the many extra stresses and strains imposed by touring, this mystified me.

Then I realized what the attraction was. Travelling press aside, tours provided her with an endless supply of new and interesting supporting casts. She liked foreigners and, of course, the only ones she met abroad were the ones who liked her. In fact, it must have seemed to her that they adored her, unreservedly and unconditionally. They did not read menacing broadsheet newspaper analyses of her waning relevance to the power of the British establishment. They did not stop to consider whether she manipulated London’s popular media. They did not question her sincerity and motives in the way increasingly favoured by her Pharisee critics back home.

It is hard to blame her if, in the end, she preferred the company of enthusiastic foreigners to the wan faces of rain-soaked, provincial England; or the simple gratitude of a limbless Pathan tribesman to the false smiles of London society; or the attentiveness of a playboy lover to the lizard-like watchfulness she felt scouring her from the drawing rooms of Gloucestershire or the smoking rooms of St James’s.

Noticing the quick approval she seemed to attract abroad, I wondered how much of the Princess’s glamour was due to her innate qualities and how much she owed to the status she had acquired on marriage. The answer, I suppose, was an intricate mixture of both. Deprived of one – as she was when she effectively relinquished her royal status towards the end – the other had less chance to shine. Only the unique conjunction of inbred talent and historic opportunity could have created such a phenomenon.

Few film stars survive the transition from big screen to real life without losing some of their glamour on the way. Having been to more than my fair share of film premieres, I can vouch for the fact that in the flesh many actors do look surprisingly unheroic. It is the same with others in public life: to retain the importance we give them, they usually need to be surrounded by the trappings of office.

Royalty is famously no exception to this rule. The history of monarchy is one of clearly visible distinctions between them and us – from Henry VIII’s outsize codpiece to the extra-width gold lace worn on today’s royal uniforms. The necessity visibly to emphasize royal people’s uniquely superior status has kept generations of courtiers happily employed, not least because of the fringe benefits that accumulate for themselves. I will not forget the hot flush of conceit that swept over me as I opened the little Gieves and Hawkes box and out tumbled my first pair of royal cyphers – little silver ‘D’s, one of which I wore with bursting pride on the shoulder of my uniform on the rare occasions when I was still required to dress as a naval officer.

Unlike mere service equerries, the advantage of hereditary leaders is that, wherever they are and whatever they wear, they usually carry the genetic badge of office that marked their ancestors for greatness. This is one of many ways in which they differ from film stars. Nevertheless, even if they could quell a mob with a single Hanoverian glare, royal people still draw comfort and strength from the familiarity of grand surroundings.

The Princess could employ these props to dazzling effect, but her need for them differed subtly from conventional royal practice. For one thing, her inherent gifts created an aura that perfectly complemented her royal status (Ruby Wax remarked that the Princess had ‘charisma you can surf off’). Returning in the royal helicopter to Althorp or her old school, she would gleefully exclaim, ‘This is the way to arrive!’ More often, however, she showed a touching disinterest in the opportunities she had to overawe impressionable people with the accoutrements of her office.

I was reminded of the truth of this one afternoon on a blustery Cambridge railway platform. I had accompanied her on a low-key visit to a drugs project in the city and, not uncommonly, for reasons of economy we were travelling by (very) ordinary train. For some reason I now forget, we were not a very happy band that day. Having given her best for the drugs project and its clientele, the Princess had little bonhomie left over for the detective and me.

Her body language was usually quite unambiguous and we had no difficulty in recognizing that she wanted to be left alone. This was a cue which, in the circumstances, we were rather mischievously happy to take. We retreated as far away as we dared – in my case into the station bookstall – and left her apparently alone among the commuters. Needless to say, we kept her under observation from our places of concealment, so I was able to monitor first her gratifying look of disquiet when she realized she really had shaken us off, and then the reaction of other travellers.

Confronted by what appeared to be the world’s most photographed woman, statuesque in high heels and a pinstripe suit and apparently unattended on their familiar platform, their reflexes were instructive. A few just failed to notice. Rather more noticed but did not want to be seen to have noticed, probably out of a decent desire not to intrude on what was presumably a private appearance. Some backed off to a safe distance and then stared. A surprising number paused, looked her in the eye and nodded different degrees of what was recognizably a bow before continuing their stroll along the platform.

The experience of being almost alone in a public place – and hence almost like an ordinary person – was one she repeated quite frequently. As well as offering a fleeting sense of normality, it did also allow her to enjoy the innocent pleasure of being the object of excited ‘is she or isn’t she?’ whispering among bystanders, most frequently in the Kensington High Street branch of Marks and Spencers where she was a familiar figure, especially in the food hall.

It could be fun. One afternoon the Princess and I were driving to Burleigh. We were in a very unremarkable Ford, with no outriders or visible escort. We needed petrol and she pulled into the next filling station. I did the man’s task with the pump, followed by the man’s other task with the credit card in the shop. By the till two boys were arguing about the identity of the woman in the driver’s seat of the maroon Granada.

‘No it isn’t!’

‘Yes it is!’

‘No it isn’t! It can’t be! She’d ’ave police motorbikes if it was Princess Di!’

‘Don’t you know it’s rude to stare?’ said the man behind the till. Still arguing, they disappeared back to their waiting mother, who was by now also looking rather intrigued by the woman adjusting her make-up in the next-door car.

As I finished paying, the man said, ‘Did anyone ever tell you your friend looks just like Princess Di?’

I followed his gaze back to the car, where the driver had put away her compact and was obviously keen to get back on the road. I furrowed my brow. ‘Now you come to mention it, in this light … I suppose there’s a passing resemblance …’

‘Looks just like her. She could make a fortune on the telly.’

SIX

TOYCHEST

An old lag on the royal scene once gave me a very good piece of advice. ‘Never forget,’ he said over one of many brimming glasses, ‘to these people you’re just a toy. They’ll wind you up and watch you whizz all over the place and then, when your spring runs down, they’ll throw you away and get another one.’

In turn, I passed on a version of this guidance whenever new recruits fell into my hands. It was a gross exaggeration, of course, and it suggested a heartlessness about our royal family that was seldom my experience. Nonetheless, I thought – and still think – that it contained a grain of truth. Deference breeds indifference. Historically equipped with employees selected for their talent in the art of brown-nosing, there is little incentive for the royal recipient to experiment with more enlightened forms of personnel management.

In time, the respective postures become institutionalized. The servants seek ways to please, tendering advice with one eye on their pensions (I should know, I did it). The masters become jaded and indifferent, prepared eventually to swap a once-loved plaything for a new model with fresh batteries. The nursery cupboard is always well stocked with replacements, selected for safety and conformity. What is more, all the discarded puppets have conveniently signed confidentiality clauses, so there will be no trouble from them.

Every generation of toys thinks it will be different for them. Somehow they will escape the fate of all their predecessors and grow old in wisdom, honour and their owners’ esteem. Inevitably, however, most will be consigned to the charity box when the restless royal eye is caught by the next novelty.

You may think, rightly, that I was prematurely cynical, but the old lag had done me a favour by wiping the new toy’s shining eagerness off my face. When I later relayed his lesson to those I thought would not have time to learn it for themselves, it saved them, I hope, the expenditure of energy necessary to court fleeting royal favour and the unhappiness caused by the inevitable eventual rejection.

It was obvious that some royal people had grown accustomed to the seasonal change of playthings and sometimes quite enjoyed it. After all, why should they be denied this harmless pleasure, since they are denied so much else? But at an early stage it dawned on me that the only thing more valuable – and more permanent – than a new toy would be a toymaker.

No sooner had I formed this theory than its truth was confirmed in a sharp little exchange. After three years of what was generally held to be exemplary duty as the Princess’s equerry, my predecessor Richard Aylard had transferred to a post that was clearly on the Prince’s side of the invisible divide running through our still joint office. In a typically nonpartisan gesture, he offered to cover for me on one of the Princess’s engagements when I was unavailable. To my surprise his offer was immediately rejected. What could this good and faithful servant have done to incur such rapid alienation? Sadly I concluded that his sin must have been to transfer his allegiance, as she saw it, to her husband. The reason was probably immaterial. ‘Once gone, always gone,’ she said, and set her face resolutely against him.

I was naive enough to be flattered by this revelation. It was one of my boss’s less endearing habits that she encouraged her current favourite toy to take satisfaction from the misfortunes of his or her predecessor. It was one of my less endearing habits that I fell for it, at least initially.

If nothing else, however, it validated my theory about the advantages of being a toymaker rather than a mere toy. From then on I made a special point of controlling as much as I could of the hiring and firing process – which, when I became her private secretary, was practically all of it. I would like to think my involvement tempered some of the Princess’s more arbitrary attempts at personnel management. In the end, though, I could not escape the reality of royal service, which is that professional performance is less important than ‘chemistry’ in determining the progress of your career (or lack of it).

From my observations of the royal family, I gradually came to the conclusion that inherited power values survival above responsibility. You might say that such considerations are irrelevant, since royalty has been shorn of all real power anyway, thanks to generations of people’s representatives ready to risk their necks in the shearing. Yet it is perhaps because of this loss that some of today’s royalty seems all the more anxious to exercise its power over the smaller domains now left to it, and these begin and end at home. To a dresser, a valet, a housemaid, a cook, a chauffeur, a butler, a lady-in-waiting or even a private secretary, the royal master or mistress still holds the power of professional life or death. At least that would be the case, but for safeguards offered by post-feudal employment legislation and the spasmodic interest of the press.

This was even more true of the power acquired on marriage by the Princess. It was not that she was unfeeling, or lacking many of the qualities associated with effective leadership. Often the reverse was true. Rather, she had an iron resolve – understandable to a certain extent – to put her own interests above everything else in every situation. She subjected most decisions to a simple test: ‘How will this action affect my reputation, power base or convenience?’ It was further evidence of her subconscious need to assert her exclusive authority over as much and as many as lay within her reach.

She applied this test to people just as much as she did to decisions affecting her public profile. Cannily, she knew that the two areas sometimes overlapped. No Queen of Hearts – even in the making – could afford to spoil the public image with revelations about unsaintly behaviour towards her own staff. Characteristically she would pre-empt such revelations with a simple denial. At the time of Anne Beckwith-Smith’s ‘retirement’, the Princess had herself quoted as saying, ‘I don’t sack anybody.’ Equally characteristically, this breathtaking piece of wishful thinking was swallowed by most people, even as the P45s accumulated.

Perhaps only the Queen herself, famously loyal to her staff, could make such a claim. It was certainly not true of the Princess. The real significance of the remark is this: she actually convinced herself it was true. Put another way, she actually thought that having an old toy – sorry, long-serving cook – declared redundant (the usual way round the law) was not the same as having him sacked.