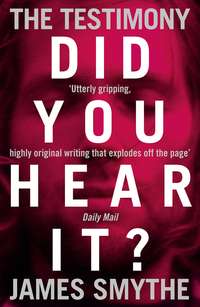

Полная версия

The Testimony

Elijah Said, prisoner on Death Row, Chicago

I was asleep when I first heard the static, in my cot. They called them cots, like we were babies. Lots of people in there didn’t sleep, defiantly staying awake, rattling anything they could against the bars, or howling their way through the nights. They would try to make sure that nobody could forget who they were, or where they were. I am a murderer, their actions called out, you would do well to remember who it is that I am, what I am capable of. It is within me to commit horrors upon you, and for that reason, I do not sleep when you tell me to; I sleep on my own timescale. On the corridor, we didn’t get exercise like the rest, didn’t get library time. Our meals were visited upon us, delivered on trays, always hot, always neatly plated, our cutlery thin shards of blunt plastic that was counted back when we were finished with our meals. If we tried anything – and I did not, but I watched as others did, unrepentant in their drive for freedom, or revenge – the cutlery was removed completely, and the prisoner ate with their hands, like a primate, free yet ignorant. The guards would laugh as they spooned potato into their mouths, with the gravy dripping through their fingers; that’s your punishment, they would say. No, I say: their punishment was both being there in the first place, behind those bars; and also would be delivered by Allah upon their death, a death that they entirely deserved for the crimes that they had committed toward their fellow man. They howled in the nights, dogs, desperate for their creator to put them out of their misery.

I could sleep through the catcalling, the constant abuse; but when a noise was unknown it would rouse me from even the deepest sleep. The static had us all on our feet, demanding to know what was happening. The guards ignored us, and left us alone. That was the first time I could remember the corridor being left unguarded; no matter how loud the shouts came for the next few minutes, the guards didn’t return, and we were briefly free from their watch to do as we pleased within those confines; for my part, I was on my musalla, praying.

The guards returned after a few minutes, when I was still praying, and they put the lights on along the corridor, demanded that we turn out. They were on edge, frantic as mice. As always, I stood back, allowed them into my cell. As always, they invaded my privacy, their trust of my people so low that they felt no shame in their intrusions. They searched under my cot, in the metal basin they called a toilet, around my person. They searched my mat, which they were forbidden to do, and they provoked me, prodded me like I was cattle, all to get a reaction. You don’t say much, do you? they asked, and I did not reply: No, I do not.

When they were gone, and the corridor was quiet again – a comparative quiet, a quiet that is still loud with shouting, but constant, our own personal take on the tranquil – my neighbour, a murderer by the name of Finkler, spoke to me. Hey, brother, he said, because he called everybody of colour that name – as if he were saying, I am one of you, the oppressed, the downtrodden, we are in this together – you know what that was? No, I replied. He carried on, even though the lights were now out, and the guards demanded silence from us: What d’you reckon it was, then? Allah will deliver answers, I said. He went quiet. Even in here he knew I could still kill him, if he didn’t go at the hands of the state first.

WE’RE HAVING PROBLEMS

Phil Gossard, sales executive, London

As soon as the TV broadcasts came back online, we expected there to be answers. There weren’t any. They actually only seemed to know as much as we did. In some ways, that was a relief, actually. I think some people expected the noise to be a signal, a warning. Some people thought it meant that we were being attacked, and who could blame them for thinking that? Biological, that was the biggest threat, but anything else, really. Nuclear, Semtex, we didn’t care. We were all so on edge because it had been what, ten years since an attack? And there were constant whispers about terrorists holing themselves up, waiting for chances. I mean, there were rumours about everything, actually, especially about the new American president (that he was, despite his campaign promises, actually more anti-war than even Obama was, a couple of terms back) and about the threat from Iran. When it was done we left the windows and switched the telly on, and it had that We’re Having Problems screen on the BBC – Aren’t we just, I said out loud, but nobody laughed – and then a minute or so later it kicked back in. It wasn’t a regular newsreader – they were interrupting whatever had been on previously, so I suppose it was whoever they had to hand, dragged up from Newsround like it was work experience week – and then they reported what had happened, that we all heard something. They went to somebody outside BT Tower, asking for opinions. Everybody they spoke to was just confused. It was strange, actually; that corner is usually a flow of people moving between Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street, but nobody was moving. They were just milling around, looking terrified or elated or whatever. Bemused, that’s the word. Most of them looked bemused.

Bill hadn’t come back from downstairs, so everybody started to look to me for answers. (I wasn’t even second in command, but if in doubt ask marketing, right?) I didn’t have a clue, so I told everybody to take the rest of the day off. Go home; see you tomorrow. Traffic’ll be shitty, you should all get a head start. Nobody left though, not immediately. We went back to the windows and watched the streets, kept the news on in the background, and waited to see if anybody could work out what the noise was.

Peter Johns, biologist, Auckland

I remember thinking, Hang on, because the scientists’ll announce something any second, tell us that they fucked up and that they’ve got it all under control. We was in this bar in Auckland and we missed the last boat back to the island because of the noise – I mean, who in their right mind is gonna get on a boat after hearing something like that? We didn’t know what it was, so we waited. Trigger, my assistant, got behind the bar after the manager didn’t want to serve us any more and just started pouring them out. The manager didn’t even care; he was out in the street seeing if anybody knew what the heck was going on. We must have been in there drinking for a couple of hours before we even got so much as a whiff of an answer.

Andrew Brubaker, White House Chief of Staff, Washington, DC

Before the static had even stopped we had POTUS locked down in his office, and the service went over Air Force One top to bottom. They could do the whole plane (offices, press seats, cabin, hold, exterior) in two and half minutes. We cut off all comms to the aircraft – radio dark, they called it – and we sat still as they checked us a second time. I mean, totally still. Not even blinking. When they were sure that the noise didn’t come from the aircraft they let us get up from our seats, start using some of the tech again. POTUS was on the phone to China as soon as the handset was passed to him, and he had the Russian PM holding, with calls to return to the Brits, the Germans, the Japanese. I heard him speaking to the Chinese President. I assure you, he was saying, this was nothing to do with us, it was a natural phenomenon, it was not an attack. It’s a fine line, he said when he hung up, because those guys are ready to bite. They’ll lash out as soon as we do. We step off the ledge first, they’ll dive in after us.

When he was making the rest of his calls I told Kerry what was going on – she was the press secretary – and told her to keep the rumours under control. Does anybody know what the fuck is going on? I asked, and she said, Not a clue, so I told her to make something up. There’s going to be a hell of a lot of confused people out there, and the last thing we need is them reacting, so we’re going to have to tell them something. The leaders of the free world couldn’t just sit there and quietly wait for an explanation to fall into our laps; we had to make that explanation happen. You can’t fly tonight, the service told us, so we got back into the cars and went back to the White House before anything else could happen. We were there within five minutes, and I was watching them fielding questions in the press room within seven.

Phil Gossard, sales executive, London

People slowly started filtering off – there was a thing somebody read on the internet about public transport being at a standstill, and we were all British, so that meant we should all rush and try to get on a bus as soon as possible – when the BBC started looking at different options for what it could be. They had an astronomer on from Oxford Uni, and he was saying that there was nothing in the sky. Couldn’t it just be a sound from deep space? asked the presenter, like that was a thing we saw every day, and the astronomer said, No, it couldn’t be, because there’s nothing there. Nothing on any of the SETI equipment, we’re getting nothing. It didn’t come from space. Are you sure? the presenter asked, and he said, Ninety-nine point nine per cent. There’s always a slight margin of error. So what could it be? they asked him, Could it be aliens? I remember this: he laughed a bit and said, At this point, anything’s possible, right? He meant it as a joke, I think, but of course they took that as a yes and ran with it. Within minutes, every single news broadcast is saying that it could be aliens that caused the static. Could be.

Simon Dabnall, Member of Parliament, London

I found myself in a McDonald’s, if you can believe that, the one down by the Dali museum (and I remember thinking how appropriate that was). It was fit to burst with children and their somehow even more high-pitched parents; but it also had the huge television screens across the back wall that showed the news all day. I watched the reporters discussing the static, sticking their microphones in everybody’s faces, trying to get opinions. They cut between them – some of them at the busier parts of W1, some of them in suburb areas, a very cold-looking man in Newcastle – and then they cut to one outside Westminster, talking about the close of session. It’s clear, the girl said, that even the government isn’t sure what to make of this curious state of affairs. No, they do not, I said to myself. (After that, the woman next to me moved her children along the bench slightly, putting her coat between myself and her daughter. She tutted. Tutted!) Then they cut to another reporter right outside where we were, microphone in the faces of the tourists, who seemed entirely confused by the whole thing. I put down my godawful coffee and went out there and watched the interviews. She kept looking over at me, as if she recognized me, but she didn’t ask me anything. Sir, I heard her say to a burly Yank in sandals and a luridly floral shirt that gaped across his gut. Do you think that the static could be the first contact we have with another race? I’ll be damned if I know, he said, but no; I would guess that it would be some sort of experiment by the government, that would be my guess. His whole family squeezed themselves into the shot to voice their opinions after him, and then all the other tourists who saw the cameras followed. Savages.

Andrew Brubaker, White House Chief of Staff, Washington, DC

I was speaking to the National Security Agency when the alien stuff started coming through on the wire, and the journalists at the back began shouting questions about it. Half of me wanted to step in, tell them that of course there weren’t any fucking aliens, but the other half … I mean, look, there weren’t aliens, clearly, but the alternative was far less palatable. We’d spent twenty years worrying about terrorism, about attacks, and all of a sudden there was this, and it would have been so easy for the press to panic about it more than they should have. As I say, we didn’t have a fucking clue what it was, but it wasn’t aliens, and we were crossing our fingers it wasn’t anything worse. I told the press office to ignore all questions about that, just deny it, keep the cycle spinning for a while until we knew what it actually was. None of them believed it was aliens anyway; they just wanted something to fill column inches, same as we did.

I was heading down the corridor past the briefing room when a journalist from the Post stopped me, asked me how we would treat the static if it was a first-contact situation with an alien race. You really want me to answer that? I asked, and he did, so I said, We would treat it like we’d treat any other sort of first contact: with extreme fucking caution.

Ed Meany, research and development scientist, Virginia

We ran so many tests. I mean, we were into tests up to our asses, you have no idea. Picture this: there were seven individual departments of governmental science, and they each had sub-departments, three or four apiece. Each sub-department was running its own tests, so there were tests on background noise levels, radiation levels, NASA stuff, security stuff, tests to do with animals, asking people what they thought it could be. I mean, anything you can imagine, we were testing for it somewhere. There were only a couple of divisions not working on it, because they worked on the stuff nobody knew about – plausible deniability and all that jazz. We were sending out single-sentence press releases through the White House press office when we eliminated something from the running, just to try and get everything under control. Everything else was standing still. Two minutes after POTUS told us to start running the tests (even though we had already started, clearly, because we weren’t the sort of assholes who waited for a go-order from somebody who had no idea what we were actually doing) there were statements put out to the press to calm the nation, urge the emergency services to keep going, to go to work as normal. We couldn’t risk a shutdown of them, all of us knew that. So he asked everybody to keep going as normal, and I think most people did, that day. We did; the TV stations did, and I’m betting that every 7-Eleven was still selling Slushies.

Mark Kirkman, unemployed, Boston

I can’t remember how long I sat in that bar and watched the TV. Hours, probably. Max, the barman, kept putting drinks in my hand, and I kept drinking them. I didn’t say anything, that I didn’t hear it, and we all just watched the news as it rolled in. They went on about the aliens for an hour, maybe more, and then finally they started asking, well, what else could it be? One of the early theories was something to do with cell phones, like that beep you get when you leave it on top of a speaker? But it didn’t stick, and that became the news cycle. What is it, what is it, over and over. An hour later, every station was answering that question by sticking anybody with an even vaguely religious background on their shows.

Meredith Lieberstein, retiree, New York City

How to divide the world into three camps over a single hour: make them pick between science, fantasy and religion. Give them a situation, a hypothetical situation, then give them three possible reasons for it happening – could be aliens, could be God, could be something we made ourselves and just haven’t worked out what yet – and ask them to choose. You choose the wrong one, the worst that happens is you choose again. So, we all took a stance, and there was a part of it that day – I’m not ashamed to tell you – that felt a bit like choosing between the side of the sane, and the side of … well, the other.

Phil Gossard, sales executive, London

There was a priest on the sofa with the BBC presenters saying that it was God speaking to us for the first time in two thousand years. (Since He first spoke to us through his son Jesus Christ, I think those were his exact words.) We can hear his voice, but of course we cannot comprehend it, he argued. The priest was old, set in his ways, you could tell. We can’t comprehend it because He’s speaking in tongues. Then he reeled off quotes from the Bible that seemed to back up his idea, if you squinted, and said that all good Christians should go to church and pray. If you believe, he said, you’ll go, because that is how you can tell God exactly how much you love Him. He’s made contact, the priest said; now it’s your turn to answer back. That just killed it. Half the office had gone by that point, trying to beat the traffic and make it home for the day; that took most of the rest. Ten minutes later, people everywhere were flooding to their nearest church. And I mean that, it’s not me being over-emphatic; the streets were clogged.

Meredith Lieberstein, retiree, New York City

Leonard wasn’t a fickle man. He was a man of conviction; that’s one of the things that I most liked about him, that most attracted me to him. He knew who he was. We saw the news reports about people flocking to their churches and synagogues or what have you, and he didn’t even blink. And our closest synagogue was only minutes away, so it would have been all too easy for him to fall back on old habits.

We watched them on TV as they divided it up – and gosh, it seems like all we did that morning was watch things happening, when you really break it down. CNN had figureheads from all major religions on within an hour, and they fought over what the static was. They didn’t say it, because I suppose they couldn’t, but it actually felt as if they were fighting about whose God it was. The Greek Orthodox priest kept nearly saying something, you could tell, then holding it back; he finally spat it out as the segment was coming to a close. What if it’s Allah, he said, or somebody else, Ganesh, Buddha; just not whoever it is that you already worship? What if you’ve got it wrong? There was this look that went across them all, then, because I don’t think that they had even considered that possibility. Typical, Leonard said. An hour spent in the presence of the maker, and already they’re starting to wonder if they picked the right team.

Dafni Haza, political speechwriter, Tel Aviv

My husband called me so many times that day that I had to put my phone onto silent, and even then the sound of the vibrations against other things in my bag was irritating, so I hid it in a drawer and then forgot about it for a while. When he actually got hold of me he was frantic. What was that? he asked me, and I said that I didn’t know. Why didn’t you answer your phone? Because I’m busy, I told him. That was a common argument we had, because … There was a time that I was with somebody else, after I was married to him. Nobody else knew but the man and my husband, and it was only once, but the trust didn’t come back. So he thought that I was seeing him again, or maybe somebody else, I don’t know. He whined about it all the time. He didn’t like that I had taken the new job, anyway. (The government in Tel Aviv is full of men, he said, when we argued about it; what he meant was, powerful men – the man I had cheated with was a powerful man, and it was a new theme, because when I had met Lev and fallen in love with him, he had been powerful too.) Look, he said, I just want to know what the static was. I’ll tell you when we know something, I said, and he said, Come on, you know now, you’re on the inside, you can tell me. I told you that I don’t know, I said, but I do know that I have work to do. You’ll tell me as soon as you find out more, okay? he asked, and I said, Fine. I love you, he said.

Jacques Pasceau, linguistics expert, Marseilles

It became this gospel, that it was the voice of God talking to us, you know? It was a definitive, apparently, because there was no other answer. We were watching the priests on the news, and the phone rang, and it was some Church-funded organization near Lyon, asking us to go and do some translation work for them. I asked them what they wanted us to translate, and the man said, Well, what He said to us, of course. I slammed the phone down, and Audrey said, What? What?, and I said, It was fucking static! You can’t translate static! Audrey said I was cutting off my nose, blah blah blah, that we could get funding out of it, somehow, that it would help the university’s reputation … I said to her, If you start going and working for these people and then you’re wrong – if it is just static – then it’s you that looks the imbecile.

I didn’t ask her, because there were other people around, but I think she thought it actually was God, you know.

Audrey Clave, linguistics postgraduate student, Marseilles

Jacques always acted like he was so much better than the rest of us, which is one of the reasons that I was so attracted to him. My mother used to joke that I only liked bad boys, and Jacques was as close to a bad boy as you got in the linguistics department of the University of Aix-Marseille, so it was only natural. We had only been on the same project for a few weeks, and we had only been seeing each other for days. I mean, really, we had kissed a few times, and other stuff, and then the static happened, and it was suddenly this big pressure cooker. People were going crazy outside – because you can’t hear God without there being implications, right? And no matter how many times people say, It might not be God, it might not be God, there was no proof, no evidence either way, so people were always going to overreact and refuse to stay calm. They gave the rest of us a bad name, I think.

We were watching France 24, and there was footage of a riot happening near Notre Dame, because there were so many people trying to get in to pray there. There were too many people in the streets, and they were too on edge for anything to stay simmering. That’s just the way it is with people. There had been so many riots over the years before it, so many people unhappy, and so much tension, because everything got worse after 9/11, you see, everything got so tense and kept on getting tenser and tenser, and that just meant that people were going to explode, sooner or later. You look at the riots in LA in the 1990s, in Seattle, in Athens, with the students, the ones in Egypt when they shut off their internet, the ones in London a couple of summers after they had the Olympics: you look at those; that’s a boiling point, and people reached it, and they were scared. How long had it been since I had last gone to church? A year, maybe. So why shouldn’t I have been scared as well?

We tried to stay focused, to get on with what we were doing before. (Now, I can’t even remember what that was. Something … No, I can’t remember.) We weren’t all happy to be there, though; some people around the offices wanted to leave, some wanted to stay. I wanted to stay, because I knew that Jacques wasn’t going to go anywhere, and I didn’t want to leave him alone. If everything was going to be fine, then there was no reason that I wouldn’t just stay there with him; and if everything wasn’t fine, then I wanted to be right there as well.