Полная версия

The Flight

BRYAN MALESSA

The Flight

for my family

Contents

Title Page Dedication Book I: Samland Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Book II: A Childhood Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Book III: The Circular Path Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Book IV: Journey To The Empire’s Centre Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Book V: Towards The New World Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Acknowledgements About the Author Copyright About the Publisher

BOOK I

Chapter 1

On 15 June 1940 a celebration took place on the small Platz, the square, in Germau in front of Karl’s parents’ shop. The previous evening’s radio broadcast had carried news of victory in Paris. The villagers nervously set up their goods to sell, hopeful that victory would quickly translate to peace. Early that morning Ida had asked her father, Günter, who had walked over from his village, to slaughter one of the few remaining pigs for the party. He wasn’t much good at butchering, but she couldn’t worry about that today: she was preoccupied with thoughts of her absent husband.

She knew Paul was safe on the outskirts of Paris where he had been sent to ensure a steady supply of food for the troops. When he had received his call-up papers he had closed their butchery because Ida hadn’t the strength or the skill to run the slaughterhouse, and the children – Karl, Peter and Leyna – were too young to train. No one in the village, including Paul, had thought it a matter for concern; everyone was certain that the war would be short and the soldiers would return as heroes. The decisive victory in Paris seemed to confirm that Paul would soon be home, she thought, as she sat on the front steps of the shop, which was also their home. Adults had gathered round the linden tree, encircled by an ornate iron railing that stood in the centre of the village square. A group of children were playing hide and seek near the trees surrounding the village, oblivious to their parents’ worries.

Suddenly Karl, her oldest, appeared from the group, sprinting towards her. He came through the gate that separated the shop from the square and sat down, panting, beside her. When he could speak, it was to ask again the question he had repeated since last evening’s broadcast: ‘When is Father coming home?’

At first she looked at him without speaking; then she said, ‘Come here.’ She wiped a smudge of dirt from his cheek with her apron. ‘I told you to stop asking.’

‘But Werner says he’s dead.’

Ida looked out at her neighbour’s son chasing Leyna through the trees. She could hear them giggling. ‘Tell Werner I’ll spank him myself if he says that again.’

‘When do we eat?’

‘Soon. Go and look after your little sister.’

Karl jumped up and ran back through the gate. As he crossed the square he stumbled on a loose cobble, then continued, darting through a group of adults. He ignored his sister and ran up the path to the church that stood at the top of a hill to see if he could spot Peter, his younger brother.

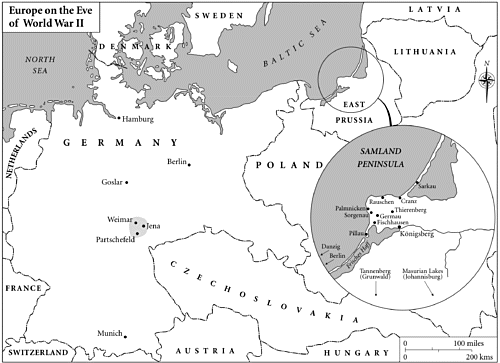

The village where Ida’s father lived, Sorgenau, was a few kilometres west of Germau, close to the amber town of Palmnicken. Günter had moved there with his Lithuanian bride shortly after Ida’s mother had died of cancer two years earlier. The roads that led to Germau dated from as far back as the Bronze Age, when the indigenous Balt-Prussians had traded their only precious resource, amber, with the outside world in exchange for metal to use in jewellery, tools and weapons. For centuries the region had remained so remote that although Tacitus and Ptolemy had mentioned it in their writings, Pliny the Elder referred mistakenly to the Samland peninsula as an island: Amber Island. Like the shards of amber that washed up daily on the local beaches, there were other bits and pieces of rarely mentioned history that marked the region: on conquering Samland seven centuries earlier the Teutonic Knights had stolen the non-Germanic tribe’s name and used it to christen their own empire. Prussia rose as one of the most militant and chauvinistic of all German states, despite the fact that many of the assimilated Baltic Prussians, including Ida’s clan, silently traced their names and lineage to a pre-Germanic past. But on that summer afternoon in 1940, no one was thinking about the village’s history as they gathered on the Platz to sing, laugh, drink, dance and make merry in honour of the news they had heard on the radio.

Ida, though, wasn’t quite ready to join the party and remained apart, nervously fingering her bracelet as she watched Karl reach the ancient church the Knights had built above the village.

‘Have you seen the sharpening stone?’ a voice called behind her.

She turned. Her father had come out of the slaughterhouse, cleaning a knife on a piece of cloth. When he saw her face he said, ‘I told you, you’ve nothing to worry about.’ He hobbled over to her and sat down beside her – always a struggle with his wooden leg. He’d lost his own defending East Prussia from the Russians in 1914 at the battle of Tannenberg. ‘Paul will be fine. The army’s in control. It will be over soon.’

Ida knew he wasn’t telling her what she wanted to hear. ‘It’s in the kitchen,’ she said, ‘in the drawer to the right of the sink.’

Günter grabbed the iron railing and pulled himself up again.

‘I’ll tell one of the children to clean the slaughterhouse,’ she said. ‘Go and join the men when you’ve finished. I must start cooking.’

‘We’ll do it together, over the fire pit. It’s you who should join the party. Come on! Up!’ He spoke to her as if she were still a child, but she stood up and straightened her dress, forced herself to smile and went out on to the square.

‘Ida!’

Romy, Werner’s mother, was coming towards her. Günter rolled his eyes and turned away.

‘Mr Badura was just telling me you managed to buy some cloth when you went to Königsberg last week. I was wondering if you had any left over – I’m trying to finish a blanket for my cousin. She’s expecting next month.’

‘I think there’s a little. I’ll have a look later.’

‘I don’t suppose you’d do it now? I wanted to finish it tonight and we might miss each other this evening.’

Ida went into her home and located the rest of the cloth with which she had made Leyna a new dress.

‘Can I give you something for it?’ Romy asked when Ida handed it to her.

‘There’s no need. My best wishes to your cousin. Now I must help my father with the pig.’

‘Would you like my help?’

‘The slaughterhouse is too small for a crowd,’ Ida said. ‘We’ll catch up later, after we’ve eaten.’

When Romy had gone Ida started to close the door but saw Leyna running through the gate, so she opened it again. ‘Mutti, Werner’s teasing me! When are we going to eat?’

‘I wish you and Karl would stop asking that.’

They walked through the house and out of the back door where they found Günter smoking and gazing into the pasture.

‘You call that work?’ Ida joked.

He dropped the cigarette, grabbed Leyna and flung her into the air as she shrieked with delight, ‘Put me down, Grandpa!’

Soon a side of pork was roasting over the open pit beside the slaughterhouse where a group of men had gathered. Each generation had its favourite songs and as the afternoon wore on the villagers began to sing. Even the boys on the square stopped playing and started to sing a Hitler Youth song they had learned from the older boys at school:

We march for Hitler through the night.

Suffering with the flag for freedom and bread.

Our flag means more to us than death…

The old men, all veterans of the last war, laughed bitterly. ‘What do they know about death?’ one muttered.

Another called, ‘Go and get us some of the bread you’re singing about. We haven’t finished eating yet.’

The children were silent – until they realised that the men were laughing at them. Then they sang even louder:

We march for Hitler through the night.

Suffering with the flag for freedom…

Chapter 2

That autumn, each Thursday after lunch, Karl, Peter and Leyna waited on the hill outside the village beside the road that led to Fischhausen. From there they could see nearly two kilometres down the long straight road as they looked for the postman, trying to guess when he would appear. The younger two had to rely on their brother’s word because he wouldn’t let them see the watch their grandfather had given him.

Once they were certain the postman was on his way, they sprinted into the woods, along the path and down the hill, across a glade and back up the opposite hill to the church. When they reached the cemetery they stopped to catch their breath, then ran down into the square just before the truck arrived.

They wanted to be ready in case their father had sent them a parcel. They were the only children in Germau who received sweets in the post each month, but they waited for the postman each week in case he had sent an extra one. Ida made them open it at home – otherwise, she knew, they’d eat it all at once. Each evening, after they had done their piano practice, she would give them a little until everything had been eaten. The children took their daily ration outside to where the others waited.

When a picture appeared in the newspaper of soldiers marching along the Champs Élysées towards the Arc de Triomphe, Karl cut it out and, in the field beside the church, showed it to the other village children, saying that his father was among the soldiers at the rear. Peter supported him although both knew that Paul hadn’t marched into the city with the troops. Karl refused to share his sweets with two boys who didn’t believe him. ‘Who else would have sent us chocolate from Paris?’ Karl asked.

The boys considered this and agreed it must have been his father. He rewarded them with a nibble that seemed more delicious than anything German.

‘Maybe my father will go to Italy,’ one said, ‘and send us something even better.’

‘Italy’s already on our side, stupid. They’ll probably send him to Africa where they don’t have sweets.’

By now they’d eaten what Ida had given them.

‘See if your mother will give you more,’ one boy said.

‘She won’t. She said it’s almost gone.’

‘Let’s go and look for the secret tunnel, then.’

Immediately the children forgot about Paris and ran off. Mr Wolff had once told Karl about a tunnel that, long ago, monks had dug beneath the church. It opened somewhere in the woods and offered a last means of escape to those besieged in the building. It had rarely been used, however, since the time of the Teutonic Knights who had trained with arms and studied military strategy with the same devotion they showed to the Virgin Mary. Mr Wolff, the local coffin maker, enjoyed sharing his knowledge of their home with the children. ‘Everyone should know their history,’ he would say.

One afternoon when Karl and Peter had stood near the doorway to his shop, listening to his stories, Mr Wolff had pulled a stone from his coat pocket. Karl had recognised it as amber – Bernstein. ‘The church was once used as the headquarters where amber disputes were settled,’ Mr Wolff told them. ‘Most of the world’s amber comes from around here.’

‘Then why aren’t we rich?’ Karl asked.

‘You’re richer than many people. You need not worry about what others think of you.’

‘What do you mean?’ Karl asked.

Mr Wolff ignored his question. Instead he told the boys that long before the church had been designated the Amber Palace, a Jewish trader had been the second person in recorded history to mention the Prussian tribe living on the Baltic coast. Ibrâhim ibn-Ya’qub had travelled to the region from Spain and recorded his findings in Arabic.

With the baker, Mr Schultze, whose shop stood opposite the butcher’s, Mr Wolff was the only other Jewish person remaining in the village. Of the two, only Mr Schultze had married – a Protestant woman from the capital. In the years after Hitler had been elected to power, the four other Jewish families in Germau had followed the example of those in Königsberg and fled to safer countries. Karl had once overheard his father asking Mr Wolff whether it was wise for him to remain in Germany.

‘This is home. Where else would I go?’ Mr Wolff had replied.

The villagers came to him occasionally as the arbiter in their never-ending disputes over obscure historical events. Since leaving home in his early twenties, Mr Wolff had distanced himself from his religion and focused on the study of history, convinced that intellectual and spiritual pursuits led to a similar end: self-knowledge and inner peace. In his early thirties he had reconsidered his rejection of formal religion after studying the Reformation. Instead of returning to Judaism, though, he had become interested in Protestantism. He didn’t formally convert, but he attended services occasionally and had even led Christians in prayer – for the first time when a family had requested he deliver a coffin to their farm. When he arrived, the widow asked if he would say a few words for her deceased husband, before helping them bury him in the family plot. He had been honoured by her request.

On the afternoon that Paul had asked him whether it was wise to remain in Germany, he had also asked Mr Wolff who he expected would help him if trouble came. The coffin maker had frowned and made no answer. As time passed, he noticed that the villagers who had once expressed independent views now accepted each new policy without question. It had begun back in 1934 with the banning of Jewish holidays from German calendars. In 1935 Mr Wolff had been excluded from the Armed Forces and forbidden to fly the German flag – which had hurt: he had always been among the first in Germau to raise it on national holidays. Then his citizenship was revoked, in line with the Nuremberg Laws, and in 1936 his assets were taxed an additional twenty-five per cent – all because of his religious heritage.

The villagers’ acceptance of each new law through the years was unsettling enough, but then, in the months following Paul’s blunt and unsettling question, Mr Wolff had noticed that friends with whom he had always been on good terms slowly began to distance themselves. The days Mr Wolff had once spent busy with work and the evenings once occupied visiting friends were soon replaced by long idle hours alone, the social life he had once cherished slowly withering away to nothing. Although Mr Wolff enjoyed spending time alone during the weekdays working and at weekends studying, he found the prospect of forced solitude disquieting. As he searched deeper and deeper within himself, his forced introspection eventually led back to memories of his childhood. With those memories came the prayers his parents had taught him and images of the temple in which his family had worshipped. As he meditated day after day, he felt himself being pulled towards the very subject for which he was being ostracised, pulled for the first time since leaving his parents’ home back to the sanctity of Judaism.

Chapter 3

Early one morning after a heavy snowfall, Mr Wolff left his shop to spend an hour or two studying in the church. He was so isolated from the community now that he no longer cared what anyone thought of his continued historical research in the archives or delving into the peninsula’s Jewish history. He crossed the square and noticed Karl near the foot of the hill. The boy looked up, saw him and ran to him. ‘Where are you going?’ Karl asked.

‘To talk to God.’

Karl looked up at the church. It was Saturday morning. ‘What about?’

‘Come with me, if you like, but you’d better ask your mother first.’

Karl glanced at the shop to see if she was near the window. ‘Will you wait for me?’

‘I’ll be in the vestry if you come.’ Mr Wolff set off up the hill.

Karl watched him for a moment, then ran home. Ida told him to carry in the day’s turf for the fire and he could go after that. When he reached the church he saw that the front door was ajar. He had never been into it alone before. He stood near the back pews and listened, then called Mr Wolff. His voice echoed round the walls, but the response was silence. Karl went back outside and looked around. Mr Wolff ’s footprints in the snow led into the building, but there were none to indicate that he had left. Karl went back inside and looked across the sanctuary to the vestry door. Through it, he could see the edge of a table. He walked up the aisle, glancing at the stained-glass window high above, went to the door and pushed it wide open. Mr Wolff was sitting at the table gazing at him.

‘What are you doing?’ Karl asked.

‘I told you earlier.’

‘Why aren’t you out there?’ Karl pointed to the pews where the villagers sat when they came up to the church alone to pray.

‘I like it here. It’s quieter.’ He motioned for Karl to sit down at the other side of the table.

Karl glanced at the bookshelves lining the walls. He was impressed by Mr Wolff ’s knowledge of history and literature, and wanted to go to the most prestigious school, but only a small percentage of children were admitted to the Adolf Hitler Schools. He daydreamed of being the first in the village to be selected. To him, Mr Wolff was a model of academic excellence, and Mr Wolff knew of his ambition. He had likewise taken an interest in Karl, partly because his inquisitive nature reminded him of himself as a child.

Karl asked him more about the Knights who had built the church in which they now sat. ‘Is it true that they fought a battle on this hill?’

‘It’s true,’ he answered. ‘This hill used to be a lookout for the ancient Prussians. After that battle the German Knights claimed the village for good. But even the ones who died conquering the village didn’t much care.’

Mr Wolff explained that the highest goal a Knight could attain was not victory in battle, but death at the enemy’s hands. ‘They believed that by defending the Virgin Mary’s honour, they defended her son and in defending her son, they defended God.’ Mr Wolff sometimes recited literary works for Karl; he said that they sometimes called themselves Mary’s Knights or the cult of Mary and that in the fourteenth century they had created a vast body of Mary-verse, which they chanted in private among themselves:

In the name of God’s mother, the Virgin,

Virtue’s vessel and shedder of piercing tears,

for the sake of avenging her only son, our Saviour,

the renowned and numerous Knights of Mary

chose death as their destiny and reward,

and riddled with deep wounds

kept open through fearlessness and Faith,

they stood among smashed spears and shields,

among godless corpses and limbs and heads

to bleed and redeem with blood

their rapturous hearts, their singing souls,

in battles brutal as the Virgin is beautiful.

Around a month later Karl glanced out of his bedroom window and saw Mr Wolff walking up the path to the church again. When he had finished tidying his room, he left the house and followed him. He went in and crept round the wall until he reached the vestry door. There he stopped, certain that Mr Wolff was unaware of his presence. Then he scraped the heel of his boot on the floor. At first, Mr Wolff ignored it, but eventually he stood up to investigate.

When Mr Wolff pushed open the door to look out into the church, Karl hid behind it. He waited until Mr Wolff turned to go back, then jumped out and shouted, ‘Achtung!’

Mr Wolff whirled round in fright and Karl laughed until his sides ached.

When Mr Wolff had recovered he said, ‘Come sit with me for a little while.’

They talked briefly about Karl’s studies, then the coffin maker asked if Karl wanted to play a game.

‘What kind of game?’

‘You can pretend you’re the Führer.’

At first Karl thought Mr Wolff was joking, but then he realised he was serious.

There was a moment’s silence, before Mr Wolff asked, ‘My dear Führer, how do you propose to run the country when the war is over?’

Without hesitating – he knew the Führer wouldn’t hesitate – Karl said, ‘We must continue helping our people – especially those living far away. We must make sure everyone is safe.’

‘Everyone?’

Karl didn’t understand the question, but answered confidently, as he knew a leader must, ‘Yes, of course.’

They continued their dialogue, until Mr Wolff ended it by telling him he would make a fine leader. Karl swelled with pride. Unlike many people he knew, Mr Wolff never paid a compliment unless he meant it.

That meeting made a deep impression on Karl. Even though he and the coffin maker had spent only a short time together, he knew the old man had taught him something important even if he couldn’t quite put his finger on what it was. When he left the church, he decided he wanted to be alone to think about their conversation. Instead of continuing towards the square, he went down the hill into the forest where the hidden tunnel was rumoured to open.

Chapter 4

In the months that followed, Karl was so busy at school that he hardly saw Mr Wolff – until one afternoon, when he glanced out his bedroom window: strangers were talking to him outside his shop and examining his identity card. He had shown it to Karl one morning when they met on the road that led from the railway station. Mr Wolff had been to the capital. Karl had studied the card, which bore a large ‘J’ imprinted in the middle.

‘They want me to change my name to Israel now,’ Mr Wolff had said. ‘Israel and Sara.’

After the men had left, Mr Wolff remained outside his shop for a long time, staring across the square. When he finally turned to go in, he saw Karl and paused, briefly, before disappearing back inside. Karl felt uneasy about having spied on him in such an uncomfortable situation.

But he felt far worse when, on his return from school a few weeks later, he discovered that Mr Wolff had gone. When Karl asked his mother what had happened she didn’t answer. A few hours later he asked her again. She told him to mind his own business. Later still, when she found him in his room, looking out of the window at Mr Wolff ’s shop, she relented. He knew something was wrong because she avoided his eyes.

‘They took Mr Schultze, too,’ she said.

‘Where did they go?’

‘I don’t know. They put them in a truck.’

‘Are they coming back?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What about his shop?’

‘I told you, I don’t know!’

He knew he should not ask any more. They stared out of the window without speaking. Ida slid her hand along Karl’s arm and clasped his hand in hers. He continued to look out of the window, first at the linden tree in the centre of the square, then at the church where he and Mr Wolff had sat together. Eventually, Karl asked if he could go outside.