Полная версия

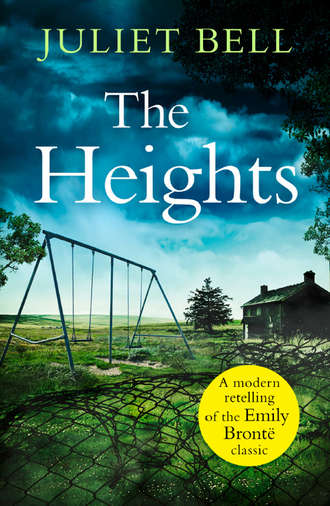

The Heights: A dark story of obsession and revenge

Two hundred years since Emily Brontë’s birth comes The Heights: a modern re-telling of Wuthering Heights set in 1980s Yorkshire.

The searchers took several hours to find the body, even though they knew roughly where to look. The whole hillside had collapsed, and there was water running off the moors and over the slick black rubble. The boy, they knew, was beyond their help. This was a recovery, not a rescue.

A grim discovery brings DCI Lockwood to Gimmerton’s Heights Estate – a bleak patch of Yorkshire he thought he’d left behind for good. There, he must do the unthinkable, and ask questions about the notorious Earnshaw family.

Decades may have passed since Maggie closed the pits and the Earnshaws ran riot – but old wounds remain raw. And, against his better judgement, DCI Lockwood is soon drawn into a story.

A story of an untameable boy, terrible rage, and two families ripped apart. A story of passion, obsession, and dark acts of revenge. And of beautiful Cathy Earnshaw – who now lies buried under cold white marble in the shadow of the moors.

The Heights

Juliet Bell

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Title Page

Author Bio

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Epilogue

Copyright

JULIET BELL is the collaborative pen name of respected authors Janet Gover and Alison May.

Juliet was born at a writers’ conference, with a chance remark about heroes who are far from heroic. She was raised on pizza and wine during many long working lunches, and finished her first novel over cloud storage and Skype in 2017.

Juliet shares Janet and Alison’s preoccupation with misunderstood classic fiction, and stories that explore the darker side of relationships.

Alison also writes commercial women’s fiction and romantic comedies and can be found at www.alison-may.co.uk.

Janet writes contemporary romantic adventures mostly set in outback Australia and can be found at www.janetgover.com.

Acknowledgements

This book was written with the help and support of many people.

First we must thank Emily Brontë for Wuthering Heights. Adapting her timeless story to our modern world was a huge challenge. We hope we’ve done her justice.

Many thanks to Jon Sawyer, for sharing his memories of troubled times and the picket lines and inspiring some of the key moments of the story.

Our thanks also go to our agent Julia Silk for believing in us and in this book, and to our editor, Clio Cornish, for her enthusiasm and love for the story we were trying to tell.

Writing a novel is a curiously solitary task, even when there’s two of you, so we must also thank all our friends and family for supporting us during the process. Special thanks to all our friends in the RNA, especially the wonderful women of the naughty kitchen. And extra special thanks to John and Paul for, well, for everything really.

And finally – thank you, dear reader, for picking up this book. We hope you enjoy it.

Dedicated to Emily Brontë, for creating a world with the enduring power to inspire readers and writers to this day.

Prologue

Gimmerton, West Yorkshire. 2007

The searchers took several hours to find the body, even though they knew roughly where to look. The whole hillside had collapsed and, although the rain had cleared, there was water running off the moors and over the slick black rubble. The searchers were concerned about their own safety on the unstable slope. The boy, they knew, was beyond their help. This was a recovery, not a rescue.

Twice during the search, the hillside started to move again, and the searchers held their breath. The blue hills were nothing but mine waste. There was no substance to them. They were as fragile as the lives of the people who lived below them on the estate that clung to the land around the abandoned pithead.

Some of the searchers had worked in that mine. Years ago. The boy they were searching for was one of their own. Almost. He had the right name, even if most of them had never laid eyes on him. They knew his family. His grandfather had worked beside them at the coalface. His uncle too had been one of them. Not the father, mind. But still, they weren’t going to leave the lad buried beneath the landslip.

The family weren’t out there on the slope. Maybe the police had told them to stay behind. But maybe not. Maybe they just hadn’t come.

They’d been looking for a couple of hours when the photographer from the local newspaper arrived. He was told to wait safely beyond the edge of the slip. But he was carrying an array of big and expensive lenses. His camera would go to the places he couldn’t.

The sun was sinking when they found him.

One of the searchers had started yet another small slip, and as the rock slid away, almost like liquid, part of the body was exposed. Carefully they had pulled him free.

The boy hadn’t died easily. Father Joseph, down at St Mary’s, was an old-fashioned priest, but there was no way this lad was going to have an open casket. His body had been pummelled by the sliding rock. The rain had washed most of the blood away, but it was still enough to make one of the men turn away and heave into the scrubby grass.

Surprisingly, the boy’s face was hardly damaged at all. Just a couple of small scrapes and a cut on his temple.

The team leader removed his rucksack and dug inside to find a body bag. Carefully, they lifted the boy and put him inside. There was a sense of relief when the bag was closed.

They carried him down from the hills. The photographer followed. He took a few pictures, but then seemed to lose interest. As soon as they reached the road, the photographer broke away and walked quickly to the warmth of his car.

The searchers carried the body to the ambulance and waited while he was gently placed inside. Then they too dispersed.

The ambulance and the police were the last to leave. The ambulance was destined for the morgue. The police car turned into the estate and parked outside one of the few houses that wasn’t boarded up and deserted.

The young constable got out, and carefully placed his hat on his head and straightened his uniform jacket. That’s what you did when you brought bad news to a family, even one that hadn’t bothered to come and join the search.

He walked up to number 37 Moor Lane and knocked on the door.

Chapter One

Gimmerton. 2008

This was the place he had almost died. Lockwood shivered. In front of him, the chain-link fence was rusted and sagging. The sign hung at an angle, the words NO TRESPASSING all but covered with dirt and grime. Beyond the fence, in the grey light of the overcast afternoon, the buildings looked dark and decayed. Odd bits of iron, stripped from the disused mining machines, lay scattered about the ground and weeds were reclaiming their place in the filthy wasteland of the deserted pit. One building was open to the elements, the remains of its roof lying in a twisted heap between the crumbling brick walls. Not a single pane of glass remained intact. The men of this town had good throwing arms. Stones hadn’t been their only weapons. Nor had windows been their only targets.

Lockwood reached into his pocket and retrieved the piece of metal he’d carried with him every day for more than two decades. The nail was twisted and bent, distorted almost beyond recognition when it was fired through the side of the police van. The newspaper reports at the time had declared it a miracle no one was injured as the nail ricocheted around the interior. Lockwood knew better. A tiny white scar on the left side of his neck showed how close death had come. After everything he’d seen in this job, that was the place his brain took him whenever he let his guard drop. To this day he still woke, sweating at night, hearing the sound of the nail gun beside his ear, and the screech of metal as the nail tore through the body of the van. He could still feel the sharp stab of pain in his flesh.

Lockwood told himself he was no coward. Even then, working with the riot squad, he’d expected danger. The miners were tough, and they were angry. Desperation had seeped into the bones of their community. They were about to lose their jobs. More than that, they were about to lose a way of life that had been with them for generations, the only way of life they knew. They were looking for a fight. He’d been green and keen, and could handle himself. He’d been trained to deal with anger, and there’d been so many moments in his career when something could have gone wrong. There’d been moments when things had gone wrong, but those weren’t the moments he carried with him. Instead he kept hold of this one, as clear and solid in his memory as the nail in his hand. Maybe because that was the first time things had gone wrong. Maybe because they’d never caught anyone. Maybe because of the randomness of the attack. But stay with him it had.

They might not have caught the person who did it, but Lockwood knew who it was. The squad had been out of the vehicle seconds after the incident, breaking up the crowd pounding on the sides of the van. As he struggled in the melee, his neck damp with his own blood, Lockwood had looked towards the nearby houses and seen him. A dark youth, with hatred on his face. He’d been no more than fifteen then and already familiar to the police. He was carrying something in his hands. Lockwood couldn’t see it clearly, but he knew in his heart it was the nail gun, and somewhere in amid the shouting he’d heard the words: ‘That Earnshaw kid.’

By the time Lockwood had fought his way through the crowd the youth was gone. He’d looked at the maze of narrow streets and identical houses in the Heights estate, and known he wouldn’t find him. They had investigated for a few days, but found nothing they could take to court. There were more pressing matters than one split second amid weeks of violence. Nobody was charged, and the incident was forgotten by everyone except Nelson Lockwood.

Darkness was falling as he turned away from the mine and got back into his car. He pulled away from the gates and began to retrace the route he’d followed that morning. The estate was even shabbier than before. Most of the people had left when the mine closed. Rotting boards covered the windows of the deserted pub. Graffiti scarred the walls of the empty shops and houses. Here and there, curtains or a light in a window showed that a house was occupied. For some people, Lockwood guessed, there was simply nowhere else to go.

His goal was the very last row of houses. A couple of the foremen had lived up here. They were the best paid and most trusted of the mine’s employees. They had also been the leaders of the strike. And they always protected their own. The hotheads who had thrown the bricks and started the fights. And a kid with the nail gun he’d stolen from the mine.

Lockwood knew what he would find at the far end of this street, where the town ended and the wild hills began. Since his last visit, someone had turned two small houses into one. It was larger than the houses around it, but not better than them. The aura of neglect and decay was almost palpable. It would take more than a coat of paint or some new guttering to erase the memories that lingered in those walls.

Lockwood didn’t need to see the light in the windows to know that the house was still inhabited. He’d checked that before leaving London on this final trip to Gimmerton. He drove past without stopping. There was plenty of time.

It took only a few minutes to drive from the past back to the present. The new estate had been built on a gentle slope below the moors. The houses were all detached with well-tended gardens. They were big and new and looked away from the mine, across the valley towards the lights of the town. The people who lived in the new estate weren’t part of the old world. They sent their kids to the right schools and drove their big four-wheel drives to Leeds and Sheffield to work in offices, rather than toiling beneath the ground they lived on. Their wives ate lunch, rather than dinner, and went shopping for pleasure not for provisions. The history of this place didn’t touch the Grange Estate.

Except for one small corner.

The house that had given the estate its name sat slightly removed from the new buildings, surrounded by a large garden. Thrushcross Grange was Victorian – the big house built for the mine owners back in the day, then used by a succession of managers after the pit was nationalised. It remained aloof from the newer buildings that surrounded it; with them but not a part of the town’s new story. Thrushcross was the old Gimmerton.

After parking his car, Lockwood removed his bag from the boot and slowly approached the house. Despite the need for a new coat of paint, it had survived the new reality far better than the Heights. But still the memories lingered. He stepped through the door and made his way to the reception desk where a young woman with an Eastern European accent waited to check him in.

‘Welcome to Thrushcross, sir. Do you have a reservation?’

He nodded. ‘Under Lockwood.’

She stared at the screen. ‘That is for a week?’

‘I’m not sure. It might be longer.’

‘It is quiet time, sir. There will be no problem to extend the booking if you want to.’

It felt strange to be walking the same hallways as the people who had intrigued – no, obsessed – him for so many years. As he entered his room, with its high, embossed ceiling and big bay window, he wondered which of them had slept here. He looked around the room trying to picture them, but suddenly shivered. It must be the cold wind off the moors, and he was tired after the long drive from London. The guesthouse had a restaurant. He’d go down and get something to eat and maybe a whisky before he tried to sleep.

Emerging into daylight the next morning, Lockwood was surprised to find a bright, still day. His restless sleep had been punctuated by the deep moaning of strong winds blowing off the moors, and the tapping of heavy rain against his window. Perhaps he’d been dreaming, his mind disturbed by reconnecting with the past.

Not even dazzling sunshine could make the town centre look appealing. It had changed in twenty-four years. It had never been smart, but now the decay was overwhelming. The few remaining shops were at the bottom end of the market – charity shops, pawnbrokers, pound stores. The two small pubs didn’t look at all inviting. Nor did the only food outlets; a grease-stained chippie and an Indian. A tired looking Co-op also served as post office. Lockwood had seen a nice pub and restaurant just outside the town, on a hill with a glorious view of the moors. That must be where the people from the new estate went. Their road skirted the town centre to take them away from here without even passing through the old town and risking getting the dust of poverty and hopelessness on their shiny new cars.

In a tiny town square, a group of youths sitting at the base of a statue watched through hooded eyes as Lockwood drove past. He remembered that statue. It was of the town hero, a footballer who had made it good in the first division, back when the first division really was first. It said a lot about Gimmerton that Lockwood had never heard of the town’s most famous son. There were more people standing near the pub. Men leaning against the walls, smoking as they waited for the doors to open. There was nothing else for them to do.

It hadn’t always been like this.

Lockwood parked his car outside the church. It had beautiful arches over ornate, stained-glass windows and a wide staircase leading to dark wooden doors. It was newly painted, perhaps to prove that God hadn’t entirely forsaken Gimmerton. Across the road from the church was a magnificent gothic edifice, no doubt built when the mine was flourishing. The stone was stained with soot. Three storeys above the ground, ornate Victorian gables towered over windows that were dark and empty. Above the door, a carving announced that this was the Workingman’s Institute.

Or rather it had been, when there was work.

Much of the strike had been planned and run from this building. Until the union had been kicked out. And ten years later, when the pit finally closed, so too had the Institute. It was open again, but served a very different role. The men and women who walked up those steps now were going to the job centre to sign on, hoping to avoid the interest of the social workers who occupied the floor above. But this morning, that was exactly where Lockwood was heading.

The cavernous hallway echoed slightly as he made his way to the stairwell. At the top of the steps, a young mother and two small children sat on orange plastic chairs in the waiting area. Their clothes looked as if they had come from one of the charity shops on the high street. The reception desk was at the back of the large, unloved room. Behind it stood a woman about Lockwood’s own age. She had the look of a someone who’d left her better days behind some years ago and her grey hair was cut in a short, severe fashion that did nothing to flatter her lined face. She glanced up as he entered and frowned.

‘Yes?’

‘I’m looking for Ellen Dean.’

The shifting of her eyes told him he had found the woman he was looking for.

‘And you are?’

‘DCI Lockwood. I have an appointment.’ He pulled his warrant card from his pocket and held it up for her to see.

‘This way.’

She led him to a small office. She took a seat behind the cheap wooden desk while Lockwood helped himself to another orange plastic chair. Miss Dean sat primly, her mouth firmly shut, waiting for Lockwood to begin.

‘As I mentioned in my email,’ he said, ‘I’m following up on a couple of incidents recently that may shed light on an unsolved case dating back some time.’

‘What case?’ Her eyes narrowed.

Lockwood sensed she was going on the defensive.

‘It goes back to the strike,’ he said, hoping to reassure her she wasn’t his target. Not now, at least.

‘That’s long gone. People don’t talk about those times much around here.’

‘I’m not so much interested in the strike, as in some of the people who were here back then. The Earnshaws and the Lintons.’

He waited for her to say something, but she simply sat there, her eyes narrowing and her mouth fixed in that firm, defensive line.

‘I believe you had dealings with both families in your role back then with social services.’

‘In this place, most people had dealings with social services.’

Lockwood nodded. ‘I’d like to start with the Earnshaws. In particular the youngest boy. Heathcliff.’

A shadow crossed her face. He could almost feel her defences rising. Was it guilt, he wondered. He’d been in plenty of meetings with plenty of social workers over the years. He’d sat through child protection conferences, and even gone out as muscle when they took the kids away. He’d seen the good ones, the ones that cared too much, the ones that didn’t care at all, and the ones that got worn down by the job. Now, here was Ellen Dean. He wasn’t sure which type she was. He reminded himself that he was here to do a job. However personal this investigation was, he was a professional. He would do what the job demanded. He arranged his face into a more sympathetic expression.

‘I’ve read the file,’ he said. ‘There’s not much detail there. The child apparently just turned up.’

‘Old Mr Earnshaw brought him back from a trip. Liverpool.’

‘And you never thought too much about it? You didn’t question where the boy came from or how Earnshaw got hold of him?’

The woman across the table bristled. ‘It was a private fostering arrangement.’

‘Really?’ Lockwood’s eyebrow inched upwards.

She nodded. ‘Perfectly legal. There was a note from the mother.’

‘That’s not in the file.’

She shrugged. ‘It was a long time ago. Things were different then. He were never reported missing. And besides…’ Her voice trailed off.

Lockwood felt a glimmer of hope. He was beginning to understand Ellen Dean now. He knew how to get what he wanted from her. ‘Please, Miss Dean…’ He leaned forward, hoping to suggest to her that they were co-conspirators in some secret endeavour. ‘Anything you could tell me about the family will help.’

The woman pursed her lips. ‘I’m a professional. I don’t engage in gossip.’

There it was. Lockwood forced himself to resist the smile that was dragging at his lips. She knew something. And in his experience, anyone who professed not to be a gossip usually was. He nodded seriously. ‘Of course not. But if there were things you think I ought to know.’ He paused for a second as she leaned slightly towards him. ‘In your professional opinion, of course. And to help with the old case. It would be good to get rid of the paperwork on it.’

‘Well…’ The woman glanced around as if checking no one could overhear. ‘There was them that said the boy was his.’

That was interesting. ‘Was he?’

‘Don’t know. He looked like a gypsy. All dark eyes and wild hair. Talked Irish an’ all.’

‘And the mother?’

‘She never came looking for him. Back then, I had my hands full. It was desperate round here. The winter of discontent and all that. There were families what needed my help.’ She straightened her back. ‘I had important things to do. More important than wondering about one brat. He was fed and housed. He was safe. There were plenty who weren’t.’

‘Of course.’ He smiled at her.

A sudden crash outside the room was followed by the sound of a woman yelling at her child. A few seconds later, the child started screaming. That was his cue.