Полная версия

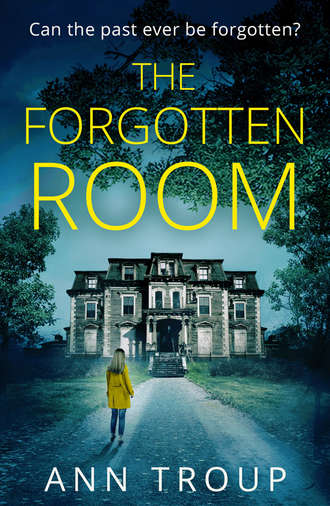

The Forgotten Room: a gripping, chilling thriller that will have you hooked

At that moment a clod of earth shifted in the bucket of the JCB and dislodged the skull, which, as if on cue, fell to the floor and rolled, landing a few inches in front of the foreman’s feet.

They were men, they found it funny and they laughed. Even the foreman allowed a smile to twitch at the corners of his mouth. And then the smirk was swiftly replaced by a grim, unsmiling line of lip when his boss answered his call.

While the workmen looked and laughed, I watched them. I saw nothing funny, no joke to be had. All I saw were thin, time-yellowed bones protruding from her grave and her head lying in the dirt, the grin on her face still as innocent as it had ever been. I had to turn away before memories added too much flesh to the dead girl’s bones. I had to turn away before I was seen and the ache in my heart made me scream.

Maura wasn’t entirely sure what had woken her. The strange hush that had fallen over the house, which it took her a few moments to recognise as the absence of noise from the building works, or the sound of the iron knocker being bashed against the front door. Either way, it was the noise of the knocking that forced her out of bed. It sounded like the iron ring had been lifted and slammed with a sense of determined urgency.

Her first instinct was to rush downstairs and check on Gordon. A man with his fixations would not react well to an unexpected intrusion. She should know – he’d spent most of the time since her arrival looking at her as if she were the spawn of the Devil, sent to try him. Well, when he was conscious anyway. He seemed to spend an inordinate amount of time sleeping, and was still dozing in his chair when she went to check on him. She had to speak to someone about his medication.

The snoozing Gordon was blithely oblivious to the voices that were coming from the drawing room. The room was a faded palace that had long ago lost its sheen, despite Cheryl’s best efforts with the beeswax polish, and it probably hadn’t seen company for years. The first surprise for Maura when she went in was the glimpse of a blue uniform through the window; the second and much more gut-wrenching one was that she recognised the detective who was perched on the edge of the ancient sofa. The last time she’d set eyes on Detective Sergeant Mike Poole she’d slapped him across the face and the memory of it made her feel sick with shame. It had been at Richard’s funeral, the last occasion on earth where she’d wanted to show herself up so badly.

Cheryl turned her head. ‘Oh, I was just going to come and fetch you. The police want to talk to us. This is Detective Sergeant Poole and this is Detective Constable Gallan.’ Cheryl pointed at the two officers with a hand that shook with nerves that were out of proportion to the casual introduction.

Maura was already aware that the colour had drained from her face when DS Poole spoke. ‘Hello, Miss Lyle. Take a seat – you’re looking a bit pale.’

Cheryl didn’t notice that he already knew Maura’s name and carried on regardless. ‘There’s been an awful discovery on the building site. They’ve dug up human remains!’

Maura looked at Poole. ‘I didn’t imagine for one minute that you’d come about the broken window.’ This place just got worse and worse, rocks through windows, dead bodies – the bloody place was a cornucopia of crap. At the realisation that her words were a mite callous, Maura had the grace to blush. Had she become that hard?

Poole frowned at her. ‘Indeed, though we do take all such incidents seriously, I don’t feel there’s a connection with our current enquiry.’

‘I don’t see that I can be of much help then. I only arrived yesterday and know absolutely nothing about anything to do with Essen Grange.’

Poole’s frown didn’t alter. ‘I don’t expect you do. However, I do need to talk to Mr Gordon Henderson and I’m led to believe he’s in a somewhat vulnerable state. Consequently, we will need you to be present.’

‘I said I’d do it, but they said I had to be interviewed too, so I can’t be the responsible adult for Mr Henderson,’ Cheryl said by way of explanation, as if not wanting anyone to think she might have been overlooked for the role. There was a thin sheen of sweat slicked across her brow. She looked profoundly nervous about the police presence and seemed to be silently pleading for something. Maura didn’t have a clue what, so turned her attention to Poole.

She could feel Poole’s gaze boring into her, going past her crumpled clothes and her tousled hair. It was as if he was trying to find out what made her tick just by staring and it made her feel brutally exposed. ‘Fair enough, but he’s asleep – I just checked so it might be better to talk to Cheryl first. I’ll try and wake him, though he might be a bit reluctant to talk to you if his routine has been disturbed.’

Poole nodded. ‘I understand he suffers from dementia.’

‘So I’m led to believe, yes.’

Maura noticed the slight rise of Poole’s eyebrows at that.

‘I’ll need to speak to the odd-job man too, and anyone else connected to the house and the land. I understand that Miss Estelle Hall is currently in hospital having suffered a serious fall, is that correct?’ He addressed his question to Cheryl, much to Maura’s relief. Just being in the same room as him was making her feel nauseous, and to think she had come here to escape reminders of the past.

‘Yes, she fell down the stairs and broke her hip. She also broke her jaw, like I said, so she won’t be able to talk to you.’ Cheryl’s voice was high and thin, a reedy note of panic wheezing through her words.

‘What happened? Which hospital?’ Poole was jotting things down.

Cheryl gave him an impatient look and spoke clearly, as if she was talking to someone who had a hard time understanding plain English. ‘She fell, down the stairs. I don’t know how it happened. I wasn’t here. You’ll have to talk to Dr Moss. I don’t know which hospital; the General, I assume.’

Poole peered at the woman, a quizzical look on his face. ‘Surely you know which hospital your employer was admitted to?’

Glad that the attention was momentarily off her, Maura fought to hide a smirk as Cheryl treated Poole to a dose of her customary charm. ‘Hardly. I’m their cleaner, not their confidante. You’d best speak to her doctor. I’m just here to keep my nose and the house clean and cook for the old man – what they get up to is none of my business. It’s an old house, they’re old people, shit happens.’

Poole’s eyebrows rose sharply this time, then he frowned and scribbled something further in his notebook. Maura would have loved to know what it said.

He snapped the book shut, a move that made his colleague start a little. Maura had suspected that Detective Constable Gallan wasn’t giving the meeting his full attention.

‘Ladies, human remains have been discovered on land that until very recently belonged to Mr Gordon Henderson. We need to know what happened and why the remains were placed there. I need to speak to people who know the area and the people, and I need to speak to the owner of this house, and anyone else who has long-standing connections with it. I would very much appreciate your help in giving me the name of anyone who fits that category.’

That he’d need to know that was patently obvious to anyone in the room with half a brain, or who had ever watched a police drama on TV. Although Maura felt that, after the previous night and just a few hours of snatched sleep, she might be functioning on less than a quarter of her own brain. ‘Isn’t it likely that the remains are old? I mean, this area is well-known as an ancient burial site. Surely the most likely explanation is that they’ve dug up some dead Roman or Anglo-Saxon or whatever.’

Poole sighed and shifted on the edge of the couch to turn towards her. ‘As an officer of the law, I assume nothing, but like you I would have preferred to think the remains were ancient. However, unless the likes of Boudicca were serving cans of coke with their spit-roast boar, I think what we can assume is that these particular remains are very modern indeed.’

Cheryl look entirely confounded. ‘Boudicca? Coke? You’ve lost me, Sergeant.’

‘It’s Detective Sergeant. A preliminary examination of the site revealed the pull-ring of a soft-drink can and a partially degraded crisp packet in a layer of soil beneath the body. It’s fair indicator that these particular remains have not been there for any significant length of time.’

Maura’s breath caught in her throat just as Cheryl allowed a horrified “Oh” to escape her thin lips.

Gordon was not happy and utterly refused to play ball with Poole. His only concern was that his lunch was due at one o’clock, it was Friday, and that it would therefore be tinned tomato soup and white bread with the crusts cut off and served in equally divided triangles. Poole shot a despairing glance at Maura, who shrugged and said, ‘Mr Henderson, would it be all right if we talked to you about this after your lunch? It is extremely important.’

‘I shall be taking my afternoon nap and will require my pills. You’ll have to come another time,’ he said, setting his mouth in a determined line while eyeing the clock. It was five to one and he was eager for his meal.

‘I’m not sure that’s going to be possible, Gordon. Is it OK if I call you Gordon?’ Maura said in a desperate effort to get the old man to comply. She wanted Poole out of the house and with no cause to return.

‘Young lady, you may not. You are expected to know your place.’ He pointed to the clock where the hands were creeping towards one.

‘Cheryl will bring it right on time, just as she always does. Mr Henderson, do you understand the seriousness of the situation? A body has been found on land that used to belong to you,’ Maura pleaded.

He looked away and a petulant, whining ring entered his voice. ‘I don’t deal with the estate. I don’t know anything about it. Talk to Estelle.’ At that point Cheryl backed through the door carrying a tray precisely as the clock struck one. There was no distracting him from it after that. Maura had seen people fixated like this before, but they hadn’t been suffering from dementia. Once Poole and his silent partner had gone, she was determined to ring Dr Moss and have a long conversation with him.

She turned to Poole. ‘I really don’t think you’re going to be able to get much from him.’

Poole frowned. ‘We’re going to have to talk to him at some point. I’ll leave it for now and maybe send a liaison officer in. It seems he might be more used to females, so maybe he’ll be more comfortable with that. In the meantime, I’ll need to see Estelle Hall, even if she’s unable to talk to me.’

Maura nodded. At least he was indicating that he wouldn’t be back. She was not a fan of the police and their tactics, but she’d rather deal with pretty much anyone than have to spend more time than was necessary with Mike Poole. ‘I’ll show you out.’ He was going to get nowhere with a woman who’d broken her jaw and more than likely listing in and out of a morphine fog.

Gallan went out first but Poole paused on the wide stone step and turned to Maura. ‘By the way, it’s nice to see you again. For what it’s worth, I really am sorry about what happened.’

It was Maura’s turn to pause, but only for a second while her better judgement vied with her more basic instincts. Instinct won. ‘What for? The fact that Richard died in a pool of his own vomit in one of your cells? Fuck you, Poole.’ She didn’t slam the door but shut it firmly in his face. Then she leaned against it, hoping he was walking away and wondering if he’d noticed how much she’d been shaking since clapping eyes on him that day. She hoped he hadn’t. It would be one humiliation too far if he had.

Gordon was already dozing in his chair, a dribble of tomato soup drying on his whiskered chin. According to the list, shaving day was Saturday and there was nothing Maura detested more than having to shave a man because he couldn’t do it for himself. Blood would be shed, albeit unintentionally. The soup sat there glistening like a little red portent, warning her of things to come.

With a stoical sigh she picked up the tray and made her way to the kitchen. Once in the passage she could hear Cheryl’s voice, high and angry.

‘As if I haven’t got enough on my plate without that filthy mutt undoing all my good work! No, Bob, I won’t have it. I don’t want that animal putting his nose around this house.’

‘Aww come on, Cheryl love, he’ll be company for her. He’s a good guard dog and after everything that’s happened you can’t expect the poor lass to sit here on her own at night, it wouldn’t be fair.’ Bob’s tone was wheedling.

‘Don’t you “love” me, Bob Silver. It won’t wash! And there’s no way her ladyship will tolerate him in the house.’

Maura was tempted to loiter in the passage until Cheryl had calmed down; the woman seemed to have a quicksilver temperament that was terrifyingly difficult to predict. The attempt at discreet avoidance was foiled by the sound of claws tapping on lino and the arrival of a wet nose followed by a furry body and a wagging tail. A dog – Maura didn’t “do” dogs but this one seemed friendly enough. At least he didn’t jump up at her like most did, but quietly followed her into the kitchen. Cheryl was on her before she could even put the tray down.

‘He,’ Cheryl said, pointing at Bob with her arm and index finger fully extended, ‘thinks you might want some protection, so he’s brought that filthy animal here. As if that fleabag could protect anyone.’ She eyed the dog with abject disdain.

Maura had to admit that the poor animal (some Heinz variety mongrel by the look of him) didn’t appear to possess the capacity to ravage anything more menacing than a tennis ball. However, if his presence would annoy Cheryl, a woman who was displaying controlling tendencies that would shame a Waffen SS officer, as far as Maura was concerned the dog could move in and sleep on the best bed. ‘Aww Bob, that’s so kind of you! What’s his name?’

‘Buster, but he’ll answer to most things, won’t you, boy?’ Bob said fondly, pointedly ignoring Cheryl’s look of utter disgust. At the sound of his name the dog began to wag his tail in a frenzy of ecstasy, a movement that set his whole body in motion and caused a large gobbet of drool to fall from his mouth onto Cheryl’s immaculate floor.

Maura could hardly contain the snigger that threatened to unleash Cheryl’s further wrath. ‘You’ll be good company, won’t you, boy?’ she said to the dog, ignoring the puce colour that had started to creep into Cheryl’s face.

The woman’s temper dissipated as quickly as it had boiled. ‘Well, yes, I suppose he can stay – but I won’t have him on the furniture and I don’t want him upstairs. She won’t tolerate it if you let him upstairs.’

A moment later it was as if it had never happened. Buster lay on a blanket under the table while Cheryl poured her trademark weak tea and Bob speculated on the identity of the body.

‘Eh, what if it’s her? What if the old boy did her in and stashed her in the woods?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, man. Drink your tea.’ Cheryl was having none of it. She turned to Maura. ‘Don’t you go listening to any of his nonsense. There’s enough going on without any of it getting furled by gossip.’

Maura gave Cheryl a weak smile and wished she would bugger off so she could ask Bob what he meant. He seemed somewhat excited, as if something had rattled him and made him overanimated. She got her wish a few minutes later when, noticing that Bob was making moves to leave, Cheryl seemed to decide it was safe for her to get on with her work. Once she was out of the kitchen, Maura was free to ask. Bob’s response was not what she’d been expecting.

‘His missus – Gordon’s. She disappeared, oh, I dunno, twenty, thirty-odd years ago? Perhaps longer. Maybe it’s her. Maybe she didn’t leave him. Maybe he bumped her off and buried her down the way. There’s plenty of gossip about it in the village, I can tell you.’

She was completely taken aback by this, not least because she couldn’t imagine Gordon ever having been married. Despite his mental health issues, he displayed an eccentric streak of obvious long duration and, in Maura’s opinion, seemed to operate from a place fuelled by a deep-seated self-obsession. Not that these things precluded marriage, but they made it less likely in her experience. ‘Did you know his wife?’

‘Me? Nah, know of her, though. It’s Connie you want to talk to. She knew her. Have a chat with her, she’ll tell you all about the Hendersons. You don’t want to listen to them in the village – I only said that to wind Cheryl up.’ He said it with a conspiratorial wink, as if it was Maura’s one desire to go digging into the family’s past and irritate Cheryl. ‘Look after the old boy, won’t you? Me and him been pals for a long time, haven’t we, Buster?’ The dog thumped his tail against the floor at this. ‘Gonna stay with the nice lady and keep her company, aren’t you, boy? Your old man’s got things to do.’ Buster ambled over and allowed his master to fuss him, revelling in the attention and slobbering to prove it.

‘I’ve never had a dog, Bob. What do I do with him? And who’s Connie?’

Her question made Bob chuckle and shake his head from side to side in a motion that smacked of bemusement. ‘Keep him off the furniture when Cheryl’s about if you can and for God’s sake don’t let him upstairs or she’ll do her nut. Other than that, not much – he’ll potter around after you. I brought some food for him. He’ll have that in the morning and evening, but other than that, not too heavy on the treats – don’t want you getting fat, do we, boy?’ He petted Buster again, who responded with the kind of adoration only a dog can display. ‘I’ll pop in to take him on his W.A.L.K in the mornings. If he’s whining by the door it means he want a pee, or the other… I’ve left you some poop bags too. He won’t stray far from the house, he’s a good old boy.’ He bent to stroke the dog’s head. ‘Connie is Cheryl’s mum. You should go and have a chat with her – she loves a natter – only don’t let on to Cheryl. They don’t see eye to eye most of the time. Funny set-up that, never could fathom it.’

Maura nodded. She didn’t relish having to pick up the poop – it was bad enough having to deal with Gordon’s toilette. ‘Thanks, Bob, you’ve been really kind.’ He had been, and she did appreciate it despite her reservations about caring for Buster, who was the least aggressive creature she’d ever come across – as a child she’d owned more terrifying guinea pigs. As for Cheryl’s mother… well, that might be something she’d willingly avoid if talking to her would irritate Cheryl. Besides, she wasn’t sure she did want to know anything more about the Hendersons. There were some stones it was better not to turn over.

Bob shrugged and put his hand on the door handle. ‘Don’t take much, does it, love? Not enough of it about in my opinion and it’s a rare thing around here. The Hendersons don’t deal much in kindness.’

Maura watched him leave and admitted he was right: there wasn’t enough kindness in the world. She should know; she’d been one of the worst culprits in its demise. She had been kind to no one in recent times, least of all herself. She had spent far too long hating the world and thinking it hated her too. But that’s what happened when the people you loved dumped on you and then died on you. You got depressed and you got mean. It was time for that to stop.

She glanced down at the dog and smiled at him ‘Time to ring the agency, I think, mate, and find out what the flipping heck is going on here.’

Having retrieved her phone, she sat in her car for a long time while Buster snuffled around in the undergrowth. She hadn’t called the agency; instead she had picked up a message from her older sister, Denise. Well, less of a message, more of a lecture. Denise had demanded that she let bygones be bygones. She demanded that Maura forgive Sarah, who was truly sorry, and insisted that Maura had to tell her where she was immediately. Finally, she had stated that she expected Maura to pull herself together after all this time and move on with her life.

Maura had listened to it twice, just to get the full nuance of her sister’s righteousness. Denise had always been bossy, had always defended Sarah and had always assumed some weird form of older-sibling dominion over Maura’s life. At thirty-eight, Maura had had enough. She sent a text saying it was none of Denise’s business where she was, that she was moving on, and that Sarah was Denise’s problem, not hers. She pressed send with grim satisfaction.

Once the text was sent she scrolled through to the number for the agency and hesitated. Breaking her contract would mean going back home, having to sit in that house, waiting for Denise to ring or visit with a list of demands and instructions that suited everyone but Maura. It would mean having to sit with the black bags that contained Richard’s belongings, wondering whether she should burn them or take them to a charity shop. It would mean going back to being unable to make the decision to do either. It would mean crawling back into the rut she’d been trying to escape for months.

It would mean leaving the Grange just when things had started to get interesting.

Chapter Six

Little heaps of pills stood like small cairns on the kitchen table; Maura had been trying to make sense of Gordon’s medication. He was asleep again and, apart from the one peeing incident shortly after she’d arrived, was proving to be the model patient. Too model. So model she was beginning to question why she had been engaged at all. Gordon didn’t appear to need a nurse, just someone who could prepare his food to his exacting standards and who could also dish out his pills in the order he preferred. And what a variety of pills there were. So far she had identified two major tranquilisers, an old-fashioned antipsychotic, two different benzodiazepines, a statin, a low-dose aspirin, what appeared to be a proton pump inhibitor, three possible sleeping tablets and a load of herbal nonsense she couldn’t identify at all. There were no packets or bottles to help, and neither was there any prescription or list – just a blue box with different compartments for various times of day, all of which were stuffed to the gunnels with pills. There wasn’t even a sticker on the box to tell her which pharmacy had dispensed the medication. All she did know was that the man she was caring for was being doped to buggery and beyond. He was barely able to maintain a simple conversation and it struck her that this had less to do with his mental state than it did with the fact that he was perpetually drug-addled.

After Cheryl had gone off to the supermarket that afternoon, Maura had rung and asked to speak to Dr Moss, only to be unhelpfully told he’d gone on leave. Her call to the local GP and request to speak to an NHS doctor had been met with a casual and patronising “I’ll see what I can do”. It had angered her, not only because she wanted to discuss Gordon’s medication, but also because she knew the receptionist hadn’t taken her seriously. No one did any longer, or so it felt. She was known at the surgery, previously as a professional, but more recently as a patient. Her rather spectacular “breakdown” had set the grapevine on fire. Now, rather than indulging in the usual banter, the staff at the surgery tended to frown at her sympathetically, speak quietly and pat her on the head (in a metaphorical sense) until she went away and stopped bothering them. It seemed to Maura that, if the mental-health nurse went mental, a point of no return had been reached. She doubted, even if a court of law had declared her sane and issued an edict, that Barb and co., guardians of the reception desk, keepers of notes and makers of appointments, would have believed it. In their eyes Maura was irreversibly flawed and permanently delicate – not to be trusted and to be treated with kid gloves for evermore.

With a sigh she piled the pills back into their little plastic reservoirs and closed the box. Without the say-so of a doctor, she could take no decisions regarding which ones she should cut out. It was an ethical dilemma she had no choice but to tolerate for the time being. Just as she’d had to tolerate Poole that day. What kind of twisted bastard was fate to put him in her path again, for crying out loud? The same kind of twisted bastard that allowed human remains to be uncovered at her place of work, she supposed. Her grandmother had often been known to use the phrase “there’s no peace for the wicked”; though Maura knew it to be prophetic in meaning, she often wondered if it was also retrospective. She felt she must have been abominably wicked in some former life to be experiencing so little peace now. Perhaps this was purgatory after all.