Полная версия

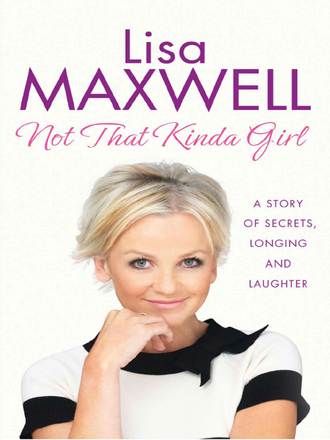

Not that Kinda Girl

For some reason Mum always thought Freddie was a saint. I used to rollerskate round the Elephant and Castle and about 8 p.m. one night I was skating in front of the Charlie Chaplin when he came past.

‘What you doing here, you little so-and-so?’ he asked. ‘Bet your mother’s worried out of her life about you. Go on, clear out of it! Clear off home and get some sweets.’

He gave me a £50 note – the highest note I’d ever seen. I gave it to Mum, who said: ‘God love him, he’s like the Pope – a god! He picks ’er up in a Corniche, buys ’er Harvey Wallbangers and sends her home in case something dodgy happens …’

My friend Danielle was beautiful, with lovely dark hair: she wore mascara and bright red lipstick, and to me she looked just like Snow White. Her mum had an antique stall on the Bermondsey Market and she gave me a keeper (friendship) ring. She was very into horoscopes, mediums and reading the future. I was once in Danielle’s room when I watched a lamp fly off the windowsill without anyone touching it. Oh God, her mum’s going to think I broke it! How was I going to tell her it just came off on its own? All she said was: ‘Don’t worry, darling – it’s only Danielle’s poltergeist.’

Danielle and me used to spend all our time together talking about boys – we even practised kissing just to know what it felt like. When I was 14 I really fancied this boy called Lee who used to sell newspapers at the Elephant and Castle. He looked cheeky and funny, like a squashed version of Mike Reid, and would call out the newspapers in a singsong voice, which I found very attractive. Danielle passed a note to him saying I fancied him and he arranged to take me out on a date. I remember he turned up in a little beige suede bomber and wore gold chains. We did have a kiss, my second ever, and I seem to remember it lived up to expectations. Funnily enough, I have clearer memories of kissing Danielle – what does that mean? But I didn’t see him again: I remember thinking myself a bit above him, which sounds snobbish, I know. I’d been brought up to believe only Prince Andrew was good enough for me.

Danielle pursued acting for a while, but family life took her in another direction. Her brother Jamie, however, in my opinion became one of the best actors of his generation.

Another of my really good friends was Suzy Fenwick, whose cousin Perry plays Billy Mitchell in EastEnders. When we were kids, Perry was appearing at the Shaftesbury Theatre in a production of Peter Pan as one of the Lost Boys. Suzy and I used to hang around with them. She fancied one of Perry’s mates, a lad called Nick Berry. We were mucking about at my flat one day when we found his phone number. Suzy rang and asked, ‘Is that Nick Berry?’ When he said yes, she replied: ‘I went through the phone book and I only found one berry, so I picked it!’ Suzie had to put the phone down – she couldn’t speak, we were laughing so much: it was really silly teenage girl stuff.

Back home, life wasn’t all rosy, though. When I was a teenager, Mum and I used to fight a lot in the way that I think sisters sometimes fight; Grandad would have to tell us to calm down. Both of us knew (and still know) which buttons to press. Our fights would be about trivial things but underlying them would be pent-up feelings about each other.

Mum never did things by half. I remember she was on tranquillisers and decided to come off them abruptly after hearing on Esther Rantzen’s That’s Life that you shouldn’t take them for more than three weeks or so. By then she’d been on them for six years. She just threw the whole lot down the toilet and went cold turkey, but you’re supposed to come off them gradually. I remember having to hold her in the night when she was freaking out – I was about 12 or 13 at the time. She was shivering, sweating and rocking her body backwards and forwards. Even after that first terrible night I’d still hear her whimpering and moaning, but she did it: when Mum decides on something, she is very single-minded.

She gave up cigarettes in the same way. When I was 18 she went to see a doctor about a cough, and when she came back she said: ‘He told me I’ve got very thin airways.’ She used to smoke 40 Consulate menthols a day but gave up there and then at the age of 40. I wish I could have had the same self-discipline: it took me several attempts to quit.

Whatever was happening at home, I still had my escape route: the train that took me to my beloved school every day, where I could sing, dance and be with my friends all day long. For me, schooldays really were among the happiest of my life.

It wasn’t always wonderful, though.

CHAPTER 4

My Secret Shame

I’d been nursing a secret for a whole week after I was summoned once again to the principal’s office. On this occasion Mrs Sheward stressed it was nothing to worry about but the staff had noticed I’d put on a bit of weight and they didn’t want it to get any worse. She told me to be careful with what I ate and said they would keep an eye on me. By then I was 13.

Afterwards I was so upset and embarrassed and I couldn’t understand it. I knew another girl who had been put on a diet but she was really fat – how could I have let myself get that big without noticing? When I looked in the mirror I didn’t see fat, but if they thought I was fat then I must be so. I kept the conversation to myself, but then it got worse, far worse: I was about to be outed as a fattie.

‘Lisa, will you come here, please. I just need to check how you’re doing with your weight.’

Having been called to the front of the class, I had to stand on some scales next to the teacher’s desk. I was mortified, more embarrassed than I’d ever been in my whole life. Now all my friends and classmates knew: I was officially fat. And that terrible feeling, as I walked from my desk to the front of the classroom, has never left me: with one massive blow it seemed to destroy the image I had of myself. No matter how many times my friends told me that I was nothing like the other girl on a diet, the damage was done. I think I was a little bit chubby. My body had started to change and fill out; I remember lying down next to one girl in jazz class doing floor exercises and just coveting her hipbones, thinking how cool it was to have your bones sticking out like that. For dancers, all the moves look better when you have thin arms and legs. In ballet classes the boys had to lift us, and this was another reason why we were more aware of what we weighed: some boys didn’t half make a meal out of it, groaning and carrying on as if they had to lift a ton of coal.

At stage school you’re in front of a mirror every day in a skimpy leotard and tights. How we looked was a big thing: we were performing children and the school made it clear from the word go that casting directors could come round at any time, picking kids for jobs or to appear in advertisements, so you always think they will choose the most beautiful and you buy into the idea that thin is beautiful. I was worried because I thought if I was chubby then when I was doing all that dancing and exercising I’d be massive by the time I left school.

I still didn’t tell Mum I’d been put on a diet. Years later, when I gave interviews about being told to lose weight so young, I described my mother going up the school to object, but this was just one of my fantasies. I never gave her chance to protest – it was my problem to deal with. Also, I never really talked to my friends about it and I didn’t cry: I just took it on the chin, absorbed it and kept any hurt buried inside me in the same way that I always dealt with difficult feelings.

Somehow, I lost the extra pounds. I’d skip school lunch, which wasn’t difficult. Mrs Stooks, who served in the canteen, always had a fag in her mouth so we’d all be focused on whether that tower of ash was about to drop into our Spag Bol. Often it did, which put us off eating there. Instead I’d head straight for the chocolate machine in the hallway. I’d get a Bar Six and a hot chocolate, then dip the Bar Six into the drink and suck the chocolate off until all that was left was the crispy bit; often that was all I had.

I think I must have developed some kind of body dysmorphia: I no longer trusted what I saw in the mirror because in my mind I was fat, end of, but that’s not what the mirror said and so what I was seeing must have been wrong. Body-conscious ever since, I can’t help but feel thin is more beautiful, although as I get older I know it can also be ageing. However, this view is deeply ingrained and although I would not become one of the anorexic ones at school I can easily see how it happened to others because it’s a very fine line.

One of my Italia Conti classmates was the brilliantly talented Lena Zavaroni, who died of anorexia just weeks before her thirty-third birthday, having battled the condition all her adult life. I was deeply sad when I heard the news of her death but, like everyone else who knew her, not surprised. I’d heard she got married and I hoped she had her life back in shape, but eating disorders are not always easy to defeat.

Just three weeks older than me, Lena had already won the Opportunity Knocks talent show and was a big star when she joined our class, but she wasn’t like Bonnie, who could handle her fame. Lena was very quiet (I remember her hardly ever speaking) and she always seemed to be on her own. No end of pupils were eager to be her friend because she had the two things we all craved, success and fame, but she was withdrawn and seemed to prefer her own company. Lena had an amazing voice (she was a good old-fashioned belter) but she was not cut out to be so far from her Scottish home and she didn’t fit in at a London stage school. She was very thin, with a head that looked far too big for her body, and massive hair.

I’m not blaming the school for Lena’s anorexia – there were plenty of other reasons in her sad life – but it’s easy to see how any girl might slip into an eating disorder. Somehow I managed to avoid it, although the demons still moved in and would come back to haunt me years later. It was drilled into us that how we looked and presented ourselves was very important. My friend Caroline was told she should always have a full face of make-up because you never knew when you might bump into a casting director. She was mortified one day when she finally met one and didn’t have her face on: she wanted to hide, but the woman commented on how pretty she was without make-up.

Despite the emphasis on looks, we did have one girl in my class who stuck out like a sore thumb. She had very irregular teeth: someone once described them as looking like ‘a row of bombed houses’. No one could work out why she was at stage school, but I thought I knew. ‘She’s probably here because they need people to work in horror movies,’ I explained, and I meant it sincerely, genuinely thinking this was a nice thing to say. Kids can be so cruel, but she played up to it, pulling faces to frighten us. I don’t think she stayed in the industry and I’m sure she grew up looking great because you can’t always tell what girls will look like at that age.

At Italia Conti there were boys, too, although they were far outnumbered. We locked one boy (Paul Gadd) into a darkroom with five or six of us and made him kiss us in turn. He rushed around in the dark, air-kissing everyone, but when it was my turn he tripped and fell onto me, so we did touch faces. Does that count as my first kiss? When he got to Danielle Foreman he lingered a bit too long for my liking, and that’s when they started going out together. By the way, I should explain Paul’s dad was the glam rock star Gary Glitter, which might explain why he was quite a troubled boy with a penchant for letting off fire extinguishers in ballet classes. I can remember Mr Sheward stomping through a tap class, yelling, ‘Either that boy goes or I do!’ Really, Paul was just mischievous and we all liked him.

Gary Glitter turned up and bought everything at one school fund-raising auction, which he then donated back to the school. Everyone thought, what a lovely generous man. We had absolutely no idea, and I feel sad for Paul now.

It must have been harder for the boys there. One, Peter, had a really fabulous soprano voice and he was a great dancer. Our singing teacher gave him hell one day when he was doing a solo because he started out as a soprano and ended up as a tenor – his voice was breaking. ‘Get out of here and work in Woolworths!’ he screamed, his standard threat to any of us who seemed to be not putting in enough effort.

I really want to apologise to a boy called Philip, also in our class: I’m ashamed to admit we bullied him horribly. It wasn’t done maliciously, we just thought it was funny, but that’s the thing about bullying – you don’t think how it feels to be on the receiving end. Philip was attractive (and straight) with thick curly hair, but girls of 12 or 13 don’t know how to behave around boys and just the fact he had an extra toilet part made him the focus of our attention. We’d sing ‘More Than a Woman’ from Saturday Night Fever with the words: ‘Philip’s a woman, Philip’s a woman to me …’ When it came to the ‘shuddup bah’ chorus we’d go ‘bah’ right in his face, then do jazz hands and dance around him. We were evil girls. In the end, his mum came up the school to complain about us and we were called in by the head of the academic side. We felt really bad, especially as Philip was moved to another class. It was such a female-dominated environment and all I ever wanted was to make people laugh, but how cruel it was.

We were given pep talks to prepare us for a life in show business. One really savage piece of advice was this: ‘You may think certain girls are your best friends, but they’re not really. If you are up for a part, and it’s down to the last two and it’s between you and your best friend, would you want your friend to get it?’ It was a way of preparing us for a tough business: more than once the staff told us only the tough would survive. I remember thinking, no, I wouldn’t like it if my best friend got a job I was after, but then I felt really guilty for even thinking it. Our school celebrated competitiveness, and it makes me laugh when I hear about schools nowadays where they don’t even have sports days because it’s not fair on the losers. We were bred to be competitive. But I don’t want to make the Italia Conti sound bad – I think girls in ordinary schools get just as many hang-ups, different ones sometimes. Conti’s was a fabulous place, a really good establishment for me to grow up in, and I can’t imagine enjoying another school anywhere near as much.

At first, being so small seemed a disadvantage. Often I was not selected for dancing jobs because they usually wanted all the dancers in a troupe to be roughly the same height. For acting, it turned out to be a plus, especially as I could play children until I was in my early twenties. And I loved acting the best – I like changing into someone else. Mum had set about changing me and I was happy to carry on with it; not just on stage or in front of the cameras, I was acting every day as if my life depended on it, and I was good at it.

Laura and I were two of the girls recruited by Dougie Squires (a top choreographer of the day) to be in The Mini Generation, a dance troupe. Back then, the New Generation were very big and we’d come on stage after them, a group of kids performing the same sort of dances. We’d dance to ‘Crazy Horses’ by The Osmonds, all bouncing around as if we’d been plugged into the mains, and we’d do another routine with umbrellas to a Shirley Temple song. We appeared at corporate events and were on TV a couple of times.

Laura, who was so talented, went on to dance with Hot Gossip when she was 16. She was touring the country doing raunchy dances and her mum was still sending her copies of Bunty! I remember she came back to school and seemed to have grown up – she had become sexy and glamorous. She could have been a megastar. Bonnie agrees with me that Laura was the most talented girl in our class, but she’s opted for marriage and a family instead. Who can blame her?

When it was announced in 1977 that a new production of Annie was being put on at the Victoria Palace Theatre in London with Stratford Johns and Sheila Hancock in the leads, there was a mass audition for the orphans. Literally hundreds of us kids turned up at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane and queued down the street with our mums. It felt like every stage-school kid in the country was there. One by one we had to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ – quite a tricky song because there’s a real leap to get to the top note. It was a deliberate choice: they didn’t want typical performing children with their pieces all prepared, they wanted natural-sounding kids.

We were whittled down to smaller and smaller groups and then called back for the moment when they line you up and announce who has got the parts. I was to play one of the orphans, but on the first day of rehearsals I was ill and when I travelled up the next day one of the other girls told me that I hadn’t got a part after all. I was ‘alternative orphan’, which meant I had to cover performances when one of the others was away: as children we were only permitted by law to do a certain number of shows each week. I knew then what they meant when they told us at Conti’s that you really don’t have friends. Perhaps I was being over-sensitive (I’d have found out as soon as I got there that I was an alternative), but I still felt the girls who landed named parts were ever so slightly gloating.

Actually, being an alternative was harder: I did three shows a week, but had to learn different parts. After a few months I was given the role of July, one of the orphans. The lead, playing Annie, was an American girl (Andrea McCardle, who had taken the part on Broadway). When she had to go back to the States we were all in tears, begging to be pen pals. I was sticking my fingers in my eyes to make tears come – I wanted to be part of the big, over-emotional farewells going on, but even though I liked Andrea I wasn’t that attached to her.

Annie was a happy time. I remember our chaperones taking us to the first McDonald’s to open in London for Big Macs. The kids who didn’t live in the city stayed in this big flat in Kensington and we all went there for parties. There was a massive sunken bath and wallpaper with shiny silver bamboo trees on it: for a long time this was my definition of posh.

Mum and the other mothers would pick us up after the show wrapped at ten o’clock at night. She would travel on the 21 bus, often with her hair in rollers to set before work the next day. We even had a Royal Command Performance in 1978. The Queen came along the row and stopped at me, asking how old I was. Even though I could imitate Received Pronunciation perfectly well, I really couldn’t understand her strangulated vowels: to me it sounded like she was speaking Dutch or something. Every time she asked the question, I said ‘Pardon?’ It was getting embarrassing, and in the end the girl next to me said, ‘She’s just saying how old are you.’ ‘Four’een,’ I replied, managing to drop the ‘t’ out of the middle of the word.

The American directors were generous to all us kids in the show, giving us presents and jewellery, usually with a cartoon of Sandy the dog on it (I’ve kept everything to give to my daughter Beau). Sheila Hancock used to meditate before she went onstage, which I later heard her say in an interview was to help calm stage fright although she never gave any hint of nerves. She bought us all a little silver disc with ‘Annie’ on it.

I kept the bust binder that I was issued with during Annie – it was to flatten our boobs so we looked like young children. I’d wear mine all the time at school because I thought it made me look thinner.

I was in the first run for six months when I was 14 and went back into the show again at 16, playing the lead role of Annie with a different cast. Onstage, we would go into school at odd times and we were put into a classroom to catch up on our academic work because by law we had to do three hours study a day. I’d be with Laura and we’d just natter, though. There was a tutor on set for the children who couldn’t get back to their schools, but we always said we were going back. I never paid much attention to schoolwork, something I deeply regret now because there are great gaps in my education, but the performing side was so much more fun.

Yorkshire Television did a documentary about the girls at the school. Of course they were interested in Bonnie and Lena but they also followed Rudi Davies, who was the daughter of the author Beryl Bainbridge. They filmed our classes, culminating in the end-of-term production. I was in the film, though not in a central role.

Rudi went on to appear in Grange Hill, the TV series about school kids. I was chosen to be in the series but, unlike her, I didn’t have a big role and was only in three episodes. That’s where I first met Todd Carty (Tucker Jenkins), who has been a mate ever since. Filming for the part came up while Mum, Nan and Grandad were away in Spain, so I had to stay with a professional chaperone. She took the job of chaperoning very seriously and would even stand outside the loo when we were in there. Whenever Mum rang from Spain she’d stand next to me, which made it hard to say how much I was missing her without sounding as if I was complaining. I remember her rather suddenly waking me up one day by dribbling cold water onto me when I wanted to keep my head on the pillow.

When we were 17, Yorkshire Television came back to see what had happened to us all (they got us together in the pub next door to Conti’s). I was one of the ones still working, so I figured more prominently in this programme.

In 1978 there was a big event for my family: the council transferred us to a house. We’d been on the list for ages and may have told one of our ‘little fibs’ about Nan and Grandad struggling with the stairs at the flats. Anyway, it worked because we were given a three-bedroom near the Walworth Road. We almost got a maisonette in a typical seventies development – all white panels and windows, clean and new looking. I was disappointed when we didn’t get it, but the house was better in the long run.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.