Полная версия

Map Addict

In fact, as a nation, we’re obsessed with this map, more so than it perhaps deserves. Don’t get me wrong; it’s good, very good indeed, even if it’s not been quite right ever since 1991, when they dropped Bank station down a bit to merge with Monument and the new Docklands Light Railway extension. Not only did this consign to the bin the legendary

Woe betide anyone whose adoration of Harry Beck’s tube map encourages them to attempt any kind of homage to it. In 2006, a self-confessed tube geek produced a quite inspired version of his own, each station faithfully rendered into an accurate anagram. Some were strangely apposite: Crux For Disco (Oxford Circus), Sad Empath (Hampstead), Written Mess (Westminster), Swearword & Ethanol (Harrow & Wealdstone) and the faintly creepy Shown Kitten (Kentish Town). Some were plain daft or bawdily Chaucerian: A Retard Cottonmouth (Tottenham Court Road), Pelmet (Temple), Burst Racoon (Barons Court), This Hungry & Boiling (Highbury & Islington), Wifely Stench (East Finchley) and Queer Spank (Queens Park). His map lit up the internet, getting over 30,000 hits in the first few days. And then the lawyers muscled in. If you Google it, you will find it, but only after coming across numerous pages telling you: ‘Content removed at the request of Healeys Solicitors acting on behalf of Transport for London and Transport Trading Ltd.’

Transport for London, whose predecessors paid Harry Beck just ten guineas for his original work, have been more than happy to license the tube map for an unholy array of tacky souvenirs. The anagram map’s creator has publicly stated that he doesn’t want any payment for it, but he wants it to be freely distributed. The idea has been picked up by artists the world over for their own transport systems. But still TfL are attempting to excise the map from cyberspace, a task only marginally less futile, and impossible, than trying to push toothpaste back into the tube. The map is a wonderful work of art: humorous, striking, colourful, beautiful. It makes Simon Patterson’s much-lauded, Turner Prize-nominated Great Bear, a Beck map where the stations are replaced with the names of artists, writers and composers, look very limp indeed. Patterson’s original was bought by the Tate, and limited prints have been snapped up for tens of thousands, by Charles Saatchi among others. It has made an awful lot of money, with full support from TfL. But then they do get 50 per cent of the proceeds, which—on the bright side—at least means that not all of their lawyers’ fees to pursue pointless causes have to come from the money you paid for your Travelcard.

It’s no coincidence that the two most lionised British maps, each dripping with myth and adoration, subjects of a glut of books, blogs and websites, are Harry Beck’s tube map and Phyllis Pearsall’s London A-Z (on which, more later). Despite the shrill claims of cities like Birmingham and Manchester, London remains our only true metropolis, effortlessly swatting away the pretensions of its minions. These two iconic maps are the fine line that separates experiencing the capital as either a cosmopolitan labyrinth of untold possibility or a coruscating pit of hell. Their overblown status in the story of our national cartography corresponds to the status of the city itself: if it happened in London, even if only in London, it is per se of nationwide significance. Although such self-regard drives us all mad in ‘the provinces’, we wouldn’t have it any other way, for who wants a capital city without a cocky swagger in its step?

There are many rather quieter examples of the best of British mapping. Harry Beck might be the patron saint of Hoxton bedsit bloggers, but for the cagoule crowd further north, the great god is Alfred Wainwright and his hand-drawn guides to the Lake District. To his legion of devotees, Wainwright represents all that is best about the stoic determination of the English fell-walker, and his precise Indian ink drawings, maps and text written in a hand that never wavered are possibly the finest an amateur has ever produced. In 1952, he decided to embark upon a series of books, carving the Lakes into seven distinct areas that encompassed all 214 fells (hills), and worked out, with pinpoint precision, that it would take him fourteen years. The last book was duly published, bang on time, in 1966. To achieve his goal, he spent every single weekend, come hell or—more often—high water, walking alone, drawing and note-taking in the mountains in collar, tie and his third-best tweed suit. On Monday morning he would return to work as the Borough Treasurer of Kendal Council, coming home to spend every evening shut away in his study, painstakingly writing up his notes of the previous weekend’s hikes. Small wonder that his wife Ruth walked out on him just three weeks before his retirement in 1967.

Wainwright became something of a reluctant celebrity in the 1970s and ’80s, playing up to his curmudgeonly image by rarely granting an interview unless the would-be interviewer trekked north to see him. Sue Lawley, for Desert Island Discs, perhaps wished she hadn’t bothered, for Wainwright was sullenly taciturn throughout the programme. The tone was set right at the outset, when she asked him, ‘And what is your favourite kind of music, Mr Wainwright?’ To which he gruffly answered, ‘I much prefer silence.’

He had started so well: his first book, The Eastern Fells, published in 1955, was dedicated to ‘The Men of the Ordnance Survey, whose maps of Lakeland have given me much pleasure both on the fells and by my fireside’. Those first seven books bristle with dry humour and an encyclopaedic eye for the crags, lakes and wildlife of his adored, adopted Cumbria (he was raised in Blackburn). In later years—and, as we’ll see, in something of an all-too-common pattern for map addicts—the dry humour evaporated into brittle bigotry. In his final book, a 1987 autobiography called Ex-Fellwanderer, he let rip with his loathing of women and how he advocated public executions, birching, a bread and water diet for all prisoners and the castration of petty criminals and trespassers. As ever, such miserly chauvinism was underpinned by a blind, blanket nostalgia. ‘These were the bad old days we so often hear about,’ he wrote. ‘But were they so bad? There were no muggings, no kidnaps, no hi-jacks, no football hooligans, no militants, no rapes, no permissiveness, no drug addicts, no demonstrations, no rent-amobs, no terrorism, no nuclear threats, no break-ins, no vandalism, no State handouts, no sense of outrage, no envy of others…Bad old days? No, I don’t agree.’ Strangely enough, at the other end of England, Harry Beck was descending into similarly obsessive and reactionary views in his latter years.

Like most egomaniacs, I can hardly listen to Desert Island Discs without mentally working on my own list for the programme. Save for a few dead certs, my choice of eight pieces of music is forever changing, but the candidate for my eternal book (aside from the Bible and Complete Works of Shakespeare) is blissfully simple and steady. Well, I’ve got it down to the final two, both map-related: the Reader’s Digest Complete Atlas of the British Isles from 1966, and, pre-dating it by a year or so, the AA’s Illustrated Road Book of England and Wales. Map addicts often reveal themselves on Desert Island Discs: plenty, including Joanna Lumley, Matthew Pinsent and explorer Robert Swan, have chosen a world atlas as their book; David Frost picked a London A-Z. Best choice, though, was that of Dame Judi Dench, who confirmed her place in the pantheon of National Treasures when she chose ‘an Ordnance Survey map of the world’ as her book in 1998.

Both of my choices are beautiful works, but I love them mainly for being such remarkable snapshots of a very specific moment in time. They are graphic, lavishly detailed pictures of the world into which I was born at the tail end of 1966. No one knew it then, but they represent a world on the cusp of fundamental cataclysm. Our industrialised island, crammed full of mines and quarries and factories and railways, was shortly to become a post-industrial place of shopping centres, theme parks, light industrial estates and speedy roads. Nineteen-sixty six was the border between those two worlds, the year that saw both the last, gruesome gasp of the old order at Aberfan, and the sapling stirrings of our future economy, a leisure industry kick-started by the English victory in the football World Cup. It was the beginning of the era when the future ceased to be the national fetish, to be replaced, ultimately and ominously, by a slavish obsession with the past.

The battle between the future and the past raged through the late 1960s and the entire 1970s, through psychedelia, sexual liberation, student uprisings, strikes, power cuts and punk, but by the time the 1980s dawned, the past had won. Margaret Thatcher, the Grantham grocer’s daughter, invoked the Britain of a bygone age to anaesthetise us to everything, from small colonial wars to her battle to destroy organised labour. Nostalgia became a driving force of the economy: the backdrop to the breakneck changes that we choose to remember is ‘Ghost Town’ and Orgreave, but it could just as easily have been the multimillion selling Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady or the spin-off frills and frou-frou by the likes of Laura Ashley. The landscape, and hence maps, began to change too: town centres, the mercantile heart of the nation for over a thousand years, wilted in the heat of the new retail parks that were mushrooming alongside new bypasses and motorways. Heritage centres, heritage railways, industrial heritage, history denuded of its scandal and gore, erupted all over the country like a pox rash.

Just how much Britain has changed in a couple of generations is witheringly evident from these two books. The Reader’s Digest Complete Atlas of the British Isles is a huge tome: 230 A3-sized pages of maps, charts, diagrams, illustrations and tiny text showing the geography of these islands in every imaginable detail, social, cultural, industrial and political, a generation on from the end of the Second World War. The book was a mammoth undertaking: the committee of consultants, listed on the second page, comprises 118 individuals and organisations, from the Ministry of Power to L. P. Lefkovitch, BSc, of the Pest Infestation Laboratory in Slough; Professor H. C. Darby, OBE, MA, PhD, LittD, to Éamonn de hóir (a mere MA) of the Ordnance Survey, Ireland. It includes a loose-leaf insert designed to promote the book, a document that oozes 1960s paternalism at its most lordly. On one side, three experts (two of whom sport florid Edwardian moustaches) sing the volume’s praises; on the other is a long list of questions, the answers to which can be found on pinpointed pages of the atlas.

‘Do you know…’ it asks, as if peering beadily at the reader over its half-moon glasses, ‘how long a Queen Ant lives? (page 110)’. Hurry to page 110, and there’s your response: ‘ten years’. ‘Where the Moscow-Washington “Hot Line” enters Britain? (page 151)’, ‘Which was the first stretch of motorway to be built in Britain? (page 147)’, ‘Where the first known human in Britain dwelt? (page 77)’, ‘The rate of air traffic at London Airport? (page 144)’ and ‘On what date the Earth is farthest from the Sun? (page 90)’. The answers being: Oban; the eight and a half miles of the Preston bypass in 1958; Swanscombe in Kent; every two and a half minutes in summer, three and a half in winter; and July 2-4.

Another section headed ‘Where in the British Isles…’ continues with such questions as: ‘…did dinosaurs live? (page 74)’, ‘…are there oil wells? (page 153)’, ‘…are the most crimes committed? (page 134)’ and ‘…do they say “mash the tea”? (page 123)’. That’ll be Dorset, Nottinghamshire, Greater London and (oddly) Flintshire, and finally, most of the Midlands and north of England.

The book is a pub quiz of gargantuan proportions. Every page has you tutting in surprise and oohing in wonder, and occasionally laughing at the chest-puffed earnestness of it all, the world as seen from the gentlemen’s clubs of SW1. According to the atlas, not only do we ‘mash the tea’ where I grew up, we say ‘I be…’ rather than ‘I am…’, drop our aitches, call a funnel a ‘tundish’ and get as pissed as an askel, rather than a newt, all of which was news to me. The most wildly diverse regional expressions seem to be for the concept of left-handedness, or keck-handedness as we had it in Worcestershire (that I do remember). Just be grateful you’re not left-handed in the Pennines (dollock- or bollock-fisted), Durham (cuddy-wifted), Galloway (corrie-flug) or Angus (kippie-klookit).

The Britain of 1966 was a nation still toiling and grafting and knowing its place. A double-page map of ‘Birthplaces of Notable Men and Women of the Past’ indicates that most of our Notable People seem strangely to have originated in the south of England: there are as many given for Somerset as for the whole of Wales (the Welsh notables, of course, do not include anyone successful only in a Welsh capacity; to warrant inclusion, they must have made it big in London or the Empire, such as Lloyd George, T. E. Lawrence ‘of Arabia’ and H. M. Stanley). And absolutely no one of worth, at least to a Reader’s Digest editor, has ever emerged from Westmorland (the only English county in this ignominious list), Anglesey, Merionethshire, Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire, Radnorshire, Flintshire, or the old Scottish counties of Wigtown, Kirkcudbright, Berwick, Peebles, West Lothian, Argyll, Bute, Kinross, Stirling, Kincardine, Banff, Nairn, Inverness, Ross and Cromarty, Sutherland, Caithness, Orkney or Shetland.

Of all the things that have most changed in the forty years since the atlas’s publication, the transport routes it portrays are the most pronounced. The infant motorway network comprised only four open routes (the M1 from Watford to Nottingham, the M2 bypassing the Medway towns and Sittingbourne, the M6 from Stafford to Preston and the reverse L of the M5/M50 from Bromsgrove to Ross-on-Wye); an optimistic map of the network to come fills in the gaps. The fact that the M5 and M6 were tarmac reality before the M3 and M4 harks back—as the map so prettily demonstrates—to the original numbering system for British A roads, where the country was divided by spokes radiating out from London. The A1 went straight up to Edinburgh, the A2 to Dover, so that all main roads between the two were numbered A1x or A1xx. The A2s were between Dover and Portsmouth, the A3s a long tranche right to the far end of the West Country, the A4s a giant wedge that took in most of the Midlands and Wales, the A5s everything between the lines from London to Holyhead and Carlisle, and the A6s the remaining backbone of England, back round to the A1. The last three numbers—A7, A8 and A9—are Scottish-only roads that were similarly centred on Edinburgh. I’m half expecting to hear from some indignant Welsh radical demanding a couple of the numbers to be reapportioned to Cardiff.

On the opposite page of this plan for the future is a rather starker image of the past, in the shape of the railway network that, by the mid 1960s, was contracting fast. Much as I squirm at the admission, I know that if I could magically transport myself into another age for a week, it wouldn’t be for a bystander’s view of the Battle of Hastings or the Last Supper, but seven glorious days, probably in May, trundling around Britain’s pre-Beeching railway network. From the very first day of my infatuation with the Ordnance Survey maps of the 1970s, it was the text reading ‘Course of old railway’ that most caught my eye, next to those spectral dashed lines tiptoeing their way across the countryside like the slug trails of history.

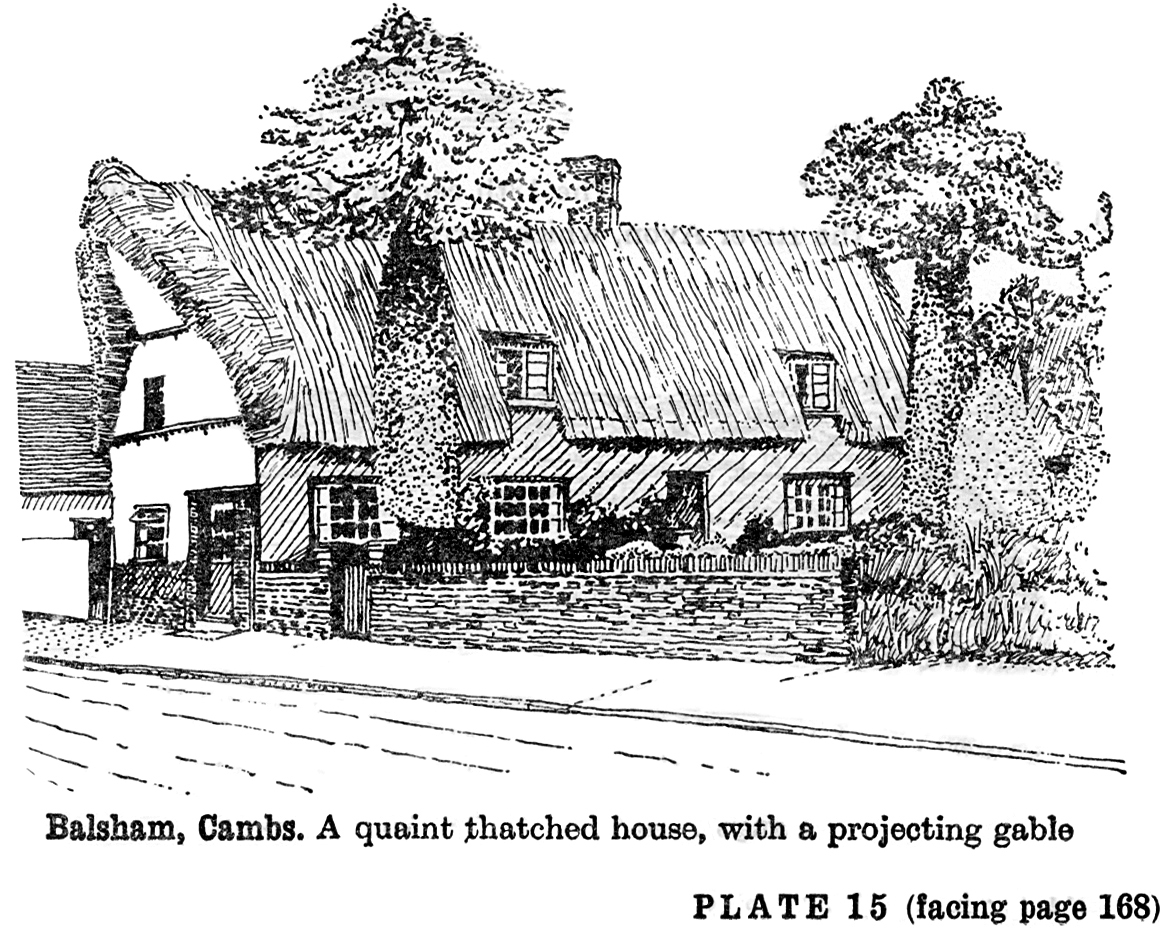

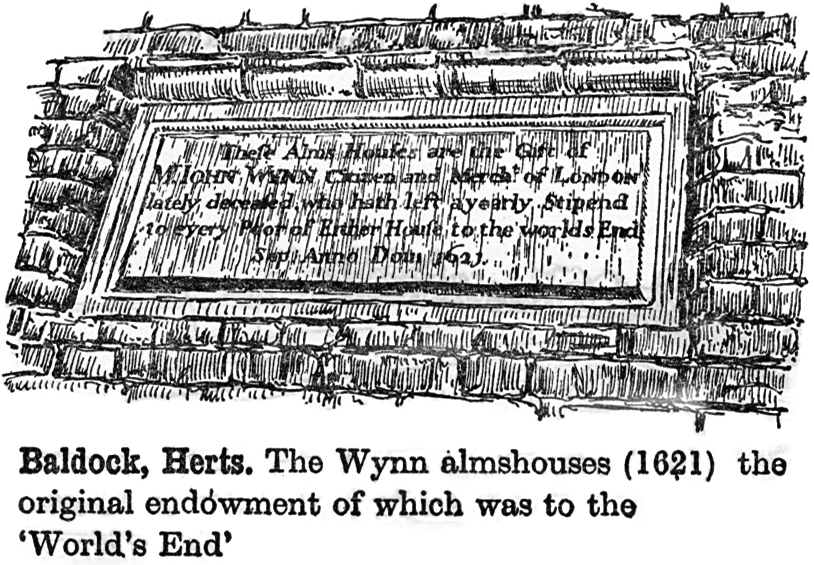

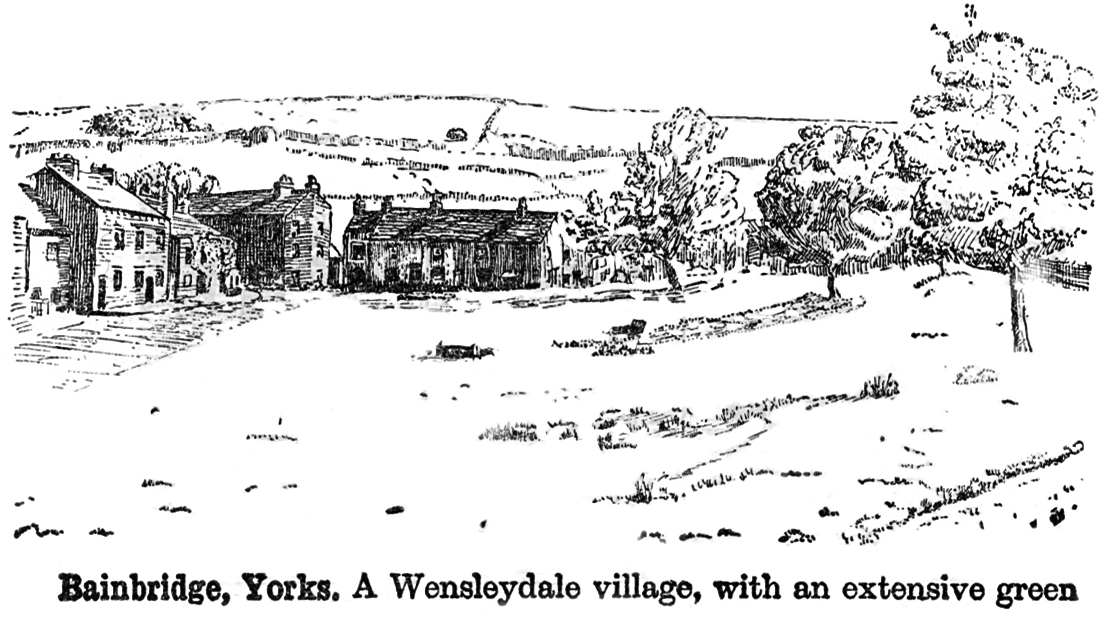

Sumptuous though the atlas is, for sheer page-turning wonder to pass the time under my palm tree, the AA’s Illustrated Road Book would probably have the edge as my final desert island choice (spending the rest of my days with a product, however good, of the Reader’s Digest couldn’t possibly be cosmically healthy). The key word is ‘Illustrated’, for the England and Wales book, and its companion tome to Scotland, are dotted with the cutest little pen-and-ink drawings of interesting things to see. Every double-page spread has a gazetteer of towns and villages on one side, and five or six drawings from these places on the other. The England and Wales volume is more than five hundred pages long; there are well over two thousand illustrations. As if that wasn’t enough, the whole country and scores of towns and cities are exquisitely mapped.

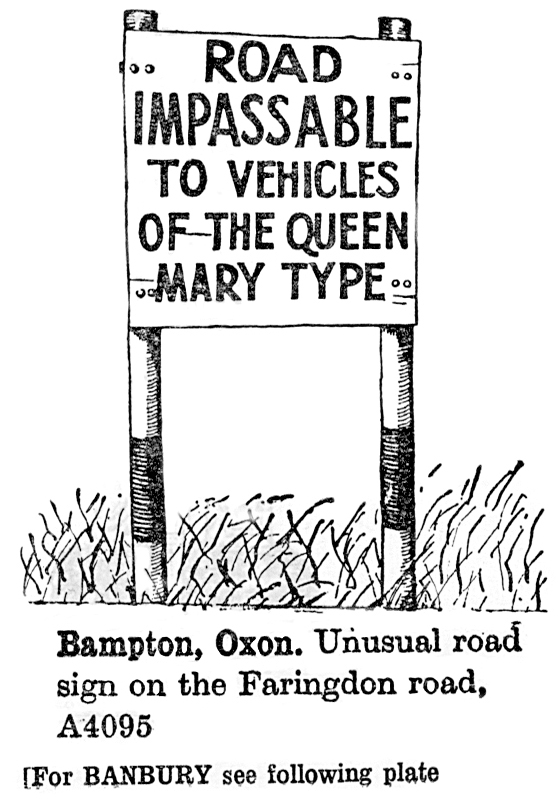

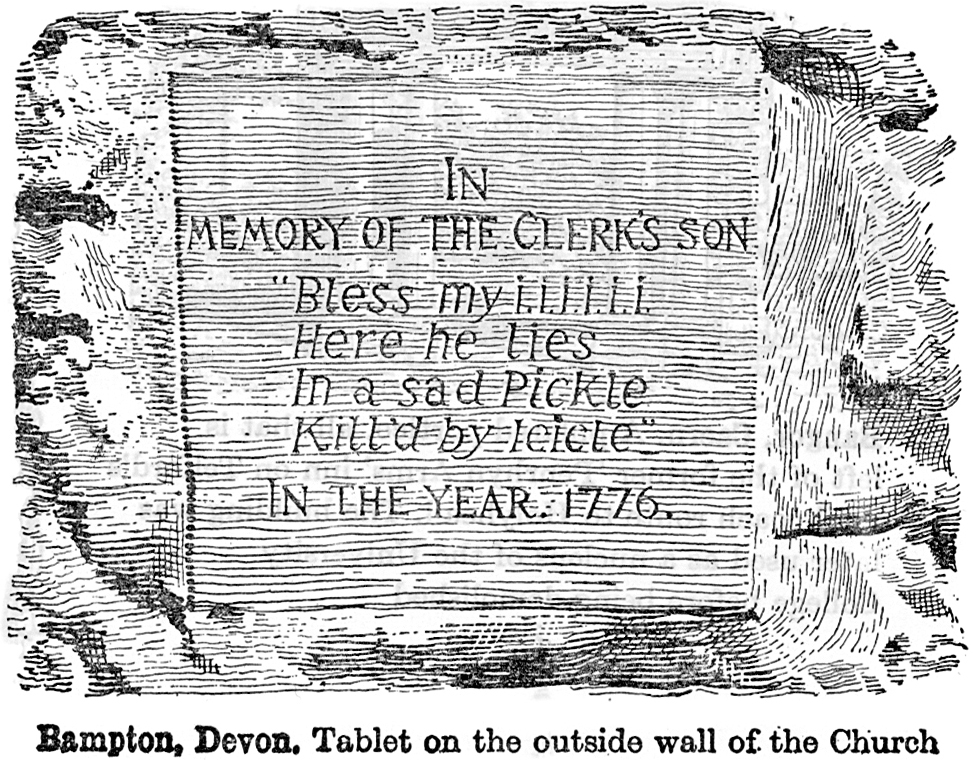

In the mid 1960s, ‘places of interest’ were not, for the most part, the things that brown tourist signs point to these days. After all, back then there were no theme parks, designer-outlet shopping malls or fully interactive heritage experiences. Instead, the book presents a dizzying array of interesting houses, churches, memorials, ruins, windmills, stones, bridges, carvings, gargoyles, inns, follies, tollbooths, plaques, graves, wells, even trees, topiary, maypoles and mazes. The illustrators had a particular fondness for unusual signposts, whether pointing down country lanes to oddly named hamlets like Pity Me, Come To Good, Bully Hole Bottom, Pennypot, Wide Open, Cold Christmas, Fryup, Wigwig, Land of Nod, Make Em Rich, New York (Lincolnshire), Paradise, Underriver, Tiptoe and The Wallops, or city street signs such as Leicester’s Holy Bones, Hull’s Land of Green Ginger, and Whip-mawhop-ma-gate in York. Other unusual signs illustrated in the book include a warning of a 1 in 2 gradient on a road outside Ravenscar, one declaring ‘Road Impassable to Vehicles of the Queen Mary Type’ at Bampton in Oxfordshire, and one on the A35 near the kennels of the East Devon Hunt stating ‘Hounds Gentlemen Please’.

It all sounds wonderfully archaic, a feast of nostalgia, but in fact the vast majority of the things featured and illustrated in this substantial book are still there. They may sometimes be a little overgrown or hard to find, but that’s part of the joy in searching them out. I’ve not

found any more up-to-date book that is so comprehensive in its sweep through the weird and wondrous features of the British landscape, and it’s still the first guide book into my camper van when I head off to amble around part of the country, particularly if it’s an area I don’t know too well. It has steered me to many memorable encounters with places and objects that represent the soul of this country, introduced me to some fascinating people and given me countless shivers down my spine as I come face to face with things I half expected to have vanished. That’s the crux of it: this book makes me feel part of a long, unbroken continuum of travellers, pilgrims and folk who just love poking their noses into their own—and others’—back yards to root around for the truffles of our national identity. Many of these pilgrims are long gone, but the spirit of their modest adventure lives on, and it will outlive any of us. I’ve known this book for decades, for my grandparents, both also gone, had a copy that I spent many quiet hours contemplating, and I was overjoyed to find my own in a second-hand bookshop in Presteigne. It still has the price—£8—pencilled on the first page; truly the finest eight quid I’ve ever spent. If I could calculate the number of hours I’ve spent combing its pages, it would easily run into several hundred, yet every time I open it, I still find something brand new that I want to go and see immediately.

The country as captured by the artists of the 1960s AA Illustrated Road Book of England & Wales

Alone on my desert island, the maps, descriptions and little sketches of the country I’d loved and lost would be a terrific condolence. The British landscape, a patchwork of astonishing variety spread over a comparatively small area, is the perfect antidote to any malaise of the spirit; I am sure that for almost any condition of the heart or head, there is a landscape to soothe and calm, or invigorate and inspire. We have a bit of everything, but not too much of anything.

A map reminds us constantly of what is possible, of how much we have seen, and how much we have still to see. This therapeutic longing for place and rootedness has its own word in Welsh, hiraeth, for it is central to the Welsh condition. Homesickness doesn’t quite cover it in English, but what cannot be readily expressed in one word has found ample expression over the centuries in art, literature and music. In the mud and madness of the First World War, it was the poetry of A. E. Housman, invoking an England of foursquare permanence and bucolic tenderness that filled the pockets of the poor bastards in the trenches. From the same war, Cotswold composer-poet Ivor Gurney was invalided back to Britain, eventually cracking under the strain of his own imagination and the horrors that he’d witnessed, and committed to an asylum in Kent. There, he would respond to nothing except an Ordnance Survey map of the Gloucestershire countryside that he adored, had explored so freely, and had written about with such vivid hiraeth. The map was a cipher for all that he loved, the last thread that connected him with life.

Our eternal love affair with our own topography is one of the defining features of being British. Of course, every country has this to some extent, but we have long honed it into an art form and an obsession. It’s the ‘sceptr’d isle’ thing, for even the frankly weird shape of our country is enough to get the juices flowing. The island of Britain is the oddest of the lot: a long, thin, slightly cadaverous outline, yet prone to sudden bulges and protuberances that hint at a fleshy softness and yielding giggle. There are the satisfying semi-symmetries of East Anglia and Wales, Kent and the West Country and the jaws of Cardigan Bay, the raw geology of Scotland’s unmistakeably bony knuckles, the little Italy of Devon and Cornwall. The island of Ireland, that ‘dull picture in a wonderful frame’, with its smooth east and shattered west, sits there knowing all too well that its larger neighbour, entirely shielding it from the European mainland, is going to be trouble.

I used to have a huge map of Great Britain and Ireland on my wall, and invite any visitors to place a pin in it where they felt that they most belonged. Some people plunged in their pins with relish, while others hovered for ages: ‘D’you mean, where I live?’ ‘No, where you feel you belong—it can be where you live if you like, but it doesn’t have to be.’ I loved to watch the mental process going on, the look of wide-eyed wonder as even people who’d never much thought about maps stared hard at the familiar shapes and let themselves mentally patrol the landscape. How differently people perceive the same place is a neverending source of fascination to me. We all have our own prejudices—justified or not—against certain locations, and we’ll go to the grave with them. There is institutional snobbery at work too, for there are, and have been for centuries, two very different maps of the country that reinforce almost every aspect of our history and identity. I call them the A-list and B-list maps of Britain.