Полная версия

Life of a Chalkstream

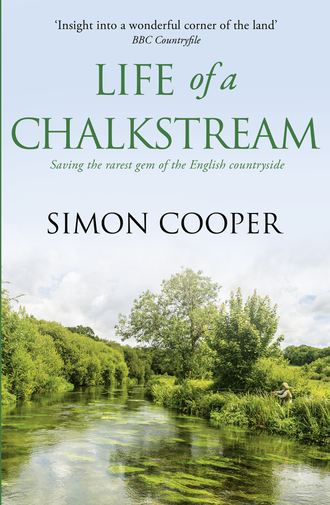

By now the geography of the river and the meadows was starting to make some sense, and as I waded upstream the structure of the place began to arrange itself before me. The main river was the spine. Coming in from the left was a bourne, a small stream that only flowed in any significant sense during the winter and early spring, so by now was near to dry. It would remain so until the autumn rains. Cutting off at a sharp angle to the right, heading due north for most of its run, was a carrier, a channel dug by hand many centuries ago whose sole purpose was to flood the meadows from February to May. Now abandoned and choked with overgrowth, the carrier was clearly once pivotal to the water-meadow system. As the channel that moved the water out of the main river across the meadows it had leats or ditches that ran off at regular intervals on both sides as conduits for carrying off the water to flood the fields. But in an arid July the leats were dry and hidden by the summer meadow grasses. Come the winter they would reveal themselves.

As I pushed on up the river the sun burnt off the cloud; it was getting warm but I still had two more things to find: the Drowners House and the brook. Wading in gin-clear water under an azure blue sky is hardly the toughest job in the world, especially in a chalkstream like the Evitt that has no great incline to it. It doesn’t race like a tidal river or rush in torrents like a mountain stream; rather it glided across the face of my waders at a gentle walking pace. Looking upstream from where I was standing I could see a full 300 yards of river ahead, and I’d be hard pushed to swear that I could see a difference in height. In fact I knew that the source, 30 miles from the sea, is only 85 feet above sea level, so that is no more than two inches’ drop in every hundred yards. For potomologists – those who study rivers – this is just about as benign a flow as a river can have.

This is a floodplain that is almost as flat as the river that flows through it, and it was only in the far distance, at least 3 or 4 miles way, that I could see the sheep-grazed downs that gradually rose to a few hundred feet. Long, long ago, in the ice age, the river valley was carved as a shallow ravine, but gradually, over millennia, the water flowing to the sea had left soil, silt, gravel and sand behind after the floods of winter, creating the flat plain on which the water meadows sit today. But nature did not do this all alone; man played his part. It is the conjunction of water with meadows that makes this such a very special landscape. There are meadows the world over, but in very few places has man harnessed the seasonal floods to irrigate and protect the grassland for the sole purpose of making the sward grow faster, lusher and more nutritious for cattle to graze. This ancient agricultural practice has, by chance and unintended consequence, created a home for a unique collection of creatures that are my constant companions.

Through a gap in the reeds I thought I spied what looked like the Drowners House some way across the meadows, with a bedraggled thatched roof covered as much by wild grass and weeds as by darkened straw. Heading for the gap to haul myself out of the river I crossed the path of a water vole swimming fast along the edge of the reeds, hugging the margin for protection. For such small creatures, seemingly so ill-adapted to water, they really can swim fast. In the water there was no way I could keep up in my waders, and on the bank I’d need to maintain a brisk walk as they stretch out their brown furry bodies, nose poked up in the air while their legs paddle like fury.

But this one, in common with all water voles, can only keep up the furious burst of speed for a short while. Quite suddenly he stopped, gave me a look with those little black eyes and with a plop disappeared beneath the surface. Under the surface things are a mad scramble for the water vole. With all that waterproof fur they are naturally buoyant, and their tiny lungs are not suited to holding their breath for long. But he had chosen to dive at this spot for a purpose. Beneath the water he wove between the roots of the reeds, heading for the bank. I could track his progress by the muddy trail he was leaving in the water until he reached the entrance to the burrow. At the tiny hole – no bigger than the size of an egg, just above water level and shiny from constant use, he stretched out the hand-like claws of his front legs, pushed them into the soft soil and using the purchase, squeezed himself inside the burrow.

Like the kingfisher, these are the breeding months for our water vole (Arvicola amphibius), which is now probably into its third or possibly fourth litter of the year, having started back in March. In the burrow, lined with dried grass torn and gathered from the bank above, anywhere between five and eight tiny voles, no bigger than your thumb, will be mewling for food. Back and forward go the adults, for anything up to eighteen hours a day. Fortunately they are pretty promiscuous in their diet on the herbivore scale. Little tooth marks on the reeds and sedges are easy to spot. Wild mint and watercress are chewed with relish, but of all the things it is wild strawberries that they fall on like mammals possessed. But really they will eat anything; the family demands it.

Doing the maths, you’d think that we’d be overrun by water voles by June – after all they are not great travellers and this one nest will have produced fifteen offspring by now. The truth is that being born a water vole is a high-risk incarnation. First, the weather might get you: lengthy bouts of bad weather, or worse still an ill-advised burrow that gets flooded. Inside the burrow you might be generally safe, but the common brown rat or worse still a stoat or mink will make short work of you and your family if you’re discovered. Once outside you are assailed from above and below: owls, buzzards, otters and pike are just four of the predators who see you as a tasty morsel. If you make it to the semi-hibernation of winter you have done well.

By now it was getting a bit hot for trudging across rough meadows in waders, so I took a direct line to the Drowners House, stumbling on the way into what were most likely carrier ditches, still soggy at the bottom beneath the tangled grasses. Ducking down under the oak lintel of the doorless entrance I entered the cool of the house. With no windows it took a few moments for my eyes to adjust to the dark, while some streaks of light came through the holes in the dilapidated thatch, illuminating the river that ran beneath the ragged floorboards. A house with a river running through it for no apparent purpose? It could only be for the drowners.

The drowners are long gone, the purpose for their livelihood disappearing when modern agricultural methods consigned the water meadows to history. But for four centuries these were the men who regulated the flow of water from the river, through the drains and carriers dug across the meadows, to quite literally ‘drown’ the late winter and spring grasses in water. Warming the soil and air of the meadows – grass grows at 5°C, chalkstream water is 10°C – plus all the nutrients the water carried with it, was the perfect way to get cattle grazing earlier and thus create heavier crops of hay. Of course all this came at a price in terms of working conditions. Obviously the times when the water levels needed most adjustment, hourly and daily, came when the weather was most foul, so the drowners built these houses. They built them over the water for the same reason they drowned the grass – warmth.

I didn’t need to take out a thermometer to check the temperature inside the house today; I knew it would be exactly the same as the water – 10°C. The thick triple-skinned red-brick walls, damp from the foundations in the wet land, helped keep the place the same temperature all year round. Today I was grateful to find it a full 10° cooler than in the sun outside, but I doubt nearly as grateful as the drowners were when the mercury fell below freezing in winter. Today, other than the house itself, there is not much evidence of the drowners’ tenure. There are soot-blackened nooks hollowed out in the brickwork as candle-holders and some initials carved in the oak beams, but the current residents are mostly house martins that have coated the walls with white guano from their nests in the rafters above.

I found myself a handy log, placed it up against the hut wall and sat down to contemplate my options. To say the river and meadows were in crisis would pitch it too strong. Severe neglect was closer to the truth; a river caught in a spiral of decline. For all the beauty of the river and the wildness of the meadows the creatures were in retreat. With every year that passed the spawning grounds were growing fewer as the streams and carriers progressively became blocked. Along the banks the scrubland was encroaching, eliminating the wide open spaces that natives like the water voles require. In the meadows, without proper grazing, the meadow plants were being crowded out. Untended, the clear, fast chalkstream waters of the floodplain would revert to a swampy morass, with insects like the olives and mayflies disappearing.

It could be saved, but was it worth saving? The answer had to be yes. The question now was how.

* I have no hard or fast rule about what to do if you don’t reach hard bottom. Generally if I am still sinking when the gloop reaches my waist I rapidly turn tail to heave myself back onto the firm bank with a fair imitation of an arthritic walrus.

2

DECLINE

THIS MORNING I found a bat caught on a hook that was dangling from a snagged fishing line on a branch overhanging the river. This is not the first time I have found bats snared like this. Bats with their super sonar hearing home in on a discarded fishing fly mistaking it for a real insect and wham, they are impaled on the hook. Sometimes by the time I find them they have died, but this Daubenton bat, the species that most commonly populate the river valley, was definitely alive and very angry.

I have heard it said that the Daubenton is the only British species to carry the rabies virus. I have no idea whether this is true, but I don’t intend to be the one to find out, so taking my handkerchief I swaddled the bat before snipping the line. Angry does not adequately describe how the brown, furry bat looked at me. The tiny black raisin-like eyes glared at me in pure fury. The pointed leathery ears that indicate the mood of the bat from gently lying back on the head (content) to being at rigid right angles to the head (agitated) were most definitely the latter. As I walked back to the Land Rover to get a pair of forceps to extract the hook from his belly I could feel his bony body twitch and turn in my hand, his head swivelling in an effort to locate the best direction of escape.

Bats have a bad press, but it is hard to feel anything but sympathy for the Daubenton for a moment or two. Though he seems exceedingly ungrateful for my help, at bay the furry head is more reminiscent of a mouse and the pink face, with wisps of downy hair, baby-like. That said, when he opens his mouth to snarl he exposes a vicious jaw full of sharp, ridged incisors designed to crush prey with one bite in flight. At the Land Rover, using an additional cloth I cover his head, trap his wings and expose the underbelly. On his back his hind legs, with claws like a bird but razor-sharp and bristly, struck wildly at the air, trying to get some purchase. The hook was caught in the belly, plumb between the legs, which made some sort of sense, for bats grab for their prey in the air with their feet. Grasping the eye of the hook with the nose of the forceps, I deftly twist my hand to remove it with one smooth movement. I am sure the Daubenton had absolutely no idea what was going on as I shook out the cloth to allow him to fly away. But he seemed to be none the worse for the experience and headed for his roost in one of the trees close by the river.

The Daubenton bats get to become regular companions if I hang around the river late into the evening anytime from May to September. The first few times I see them in May I get to do something of a double-take as the small, unfamiliar black shapes zip around the air. By now in September they are part of the furniture, and I can set my watch by them, as they appear almost exactly ninety minutes after dusk each evening. They are voracious feeders of chalkstream insects; midges are a particular favourite as they can swoop through the clouds of chironomids that gather above the river surface on calm evenings. Sometimes the bats will even take the hatching midge pupa from the surface, trawling their hind legs through the film. I am guessing it is those bristles on their feet that ‘sweep’ up the insects from the water that allow them to do this.

The bats patrol the air close to the river, high above the trees and everywhere in between for hours on end each evening for food, not just singly but in groups appearing from the trees closest to the river where they roost during the day. They sometimes, but not often, make a little squeak in flight. It is often described as a click but it never seems that way to me, but rather like the modulated squeak from a dog toy. But soon I will hardly see or hear them at all as they mate, become solitary and spend the winter in a safe roost.

September, the month of autumn fruitfulness, is a time of departures and preparations – everyone and everything in the river has its way of taking nature’s cue of the impending winter. The adult swans thrash up and down the river to chase away their cygnets, creating chaos for anglers and other birds alike. After a few days the cygnets get the hint and take flight. Woe betide any youngster who tries to return. The male cob swan will have no qualms about a full-on attack, mounting the much smaller cygnet, biting his neck, smashing down with his wings and pushing the young bird beneath the surface until the point is made. The departure of the swallows is altogether a more orderly affair, daily gathering in greater and greater numbers until quite suddenly one day they have gone on the long migration to South Africa, to return in April. Along the banks the water voles revel in the autumn harvest of hazelnuts, blackberries, seeds, acorns and whatever else falls to the ground. In the meadows the farmers put out the cattle to get the last and best of the grazing. In the river the trout, sensing the onset of autumn by the shortening days, start to feed in earnest on a spectacular array of insects that hatch in great numbers to capture the last truly warm days of the year.

For fishermen September is often termed the month ‘the locals go fishing’, on the grounds that it is the best month and best-kept secret in the piscatorial calendar. But maybe, like the creatures, we anglers also sense another season drawing to a close and get just a little frantic to enjoy the last of it before the bar comes down. For me it is always the first flurry of autumn leaves blowing onto the surface of the river that tells me the end of the season is around the corner. If I am fishing it can be a little annoying, difficult to pick out my fly amongst the blow-ins, but whether I’m fishing or just walking the banks, the sight of dead brown leaves makes me sad for the end. But this year I am buoyed by the plans we have to restore Gavelwood, which will start immediately the fishing season has closed and continue through the winter.

Gavelwood, the land, the river, side streams, brook and water meadows, takes its name from a wood that makes up part of this tiny, forgotten part of England. The woodland, a mixture of native trees like oak and ash, is as unkempt as the meadows it borders. Nobody knows where the name came from, but it is clearly marked on the deeds of ownership. The medieval word ‘gavel’ meant to give up something in lieu of rent, so maybe in some distant century the lumber was exchanged for tenure. But here today I am not here for any timber, it is the river that is the draw. A beautiful chalkstream called the Evitt that runs gin-clear, the perfect home for fish and water creatures that thrive in a habitat that is as endangered and as worthy of protection as any tropical rainforest or virgin Arctic tundra.

The water that flows through the chalkstreams is a geological freak of nature, almost unique to England. There are a few chalkstreams in Normandy, northern France, and one is rumoured to exist in New Zealand, but taken as a whole 95 per cent of the planet’s supply of pure chalkstream water exists only in southern England. The water I watch flow by in the river today fell as rain a hundred miles to the north six months ago, was deep underground yesterday and will be in the English Channel in a few hours’ time, a cycle that has been repeating for tens of thousands of years since the last ice age ended.

A chalkstream river valley today is a tamed version of how it started out. After the ice age it would have been little more than a vast, boggy marshland, with no river to speak of but rather thousands of streams, rivulets and watercourses that randomly flowed this way and that. At some point in time, it is hard to say exactly when, the early Britons must have started to use the valleys for a purpose, initially farming, which involved draining the land. Inevitably drainage involved reducing the myriad streams to a few channels, which in turn became the rivers that have evolved into the chalkstreams we have today.

It has been a mighty long process: five or six millennia for sure. The barges that carried the stones for Stonehenge were brought up what is now the Hampshire Avon, probably widened and straightened for the purpose, from where it enters the sea at Christchurch Harbour 33 miles from Amesbury, the Avon’s closest point to Stonehenge. But these incremental activities changed the river valleys very slowly, and it was the advent of the watermills that was to prove the penultimate step on the way to the chalkstream valleys we see now.

Again it is hard to pinpoint precisely when watermills became a regular part of the landscape. One thing is for sure, there are plenty listed in the Domesday Book, so it is fair to assume that the valleys were taking shape to meet the requirements of water power by this time. Essentially the mill wheel requires a good head of water to drive it, so a special channel would be dug to supply the water to drive the wheel. This ‘millpond’ would be controlled by a series of hatches, which when opened would turn the wheel for a few hours. Once depleted, the hatches would be closed and the millpond given time to refill from the river and streams.

The unintended outcome of all this would be to drain the land in the immediate vicinity, which in turn created the most wonderfully rich grazing pasture on the alluvial soil left behind after many millennia of flooding. This bounty of nature did not go unnoticed, so over the centuries that followed the river valley was gradually drained not just for the mills but for farming. The water was concentrated into a single channel which is the River Evitt today, supplemented by the side streams and ditches that provide the drainage.

But the story has one last twist. Having deprived the land of the flooding, the farmers realized that they were taking away one of the very things that had made it so productive in the first place – the nutrient-rich water that every winter washed over it. So around the seventeenth century, as the agricultural revolution took hold, landowners realized that drainage alone was not the answer and that managed flooding would dramatically increase the yield from the land, so the water meadows came into being.

By digging carriers, or leats, quite literally streams that carry water away from the main river, redirecting side streams, filling in others and creating a series of hatches to manage the flow of water, the farmers were able to use the winter and spring flows to flood the meadows from February to May. The term flooding is something of a misnomer; deep, static water over the grass would do little more than rot it away. The skill in floating, the creation of a water-meadow system, is to keep a thin layer of water constantly moving over the surface. The warmth of the water and the protection from frost, plus the nutrients carried in from the river, allow the grass to grow earlier and quicker. When ready for grazing the cattle would be let in, to be taken off when they had eaten it down and the land reflooded. If this all sounds a laborious process, it probably was. It was far beyond the daily regime of the farmers who banded together to employ a drowner, or waterman, who regulated the flows.

Today drowners are a long-distant memory, the advent of artificial fertilizers sounding the death-knell for the meadows from the early 1900s. When the watermills finally stopped grinding a few decades later, the raison d’être for this integrated water system would have all but disappeared except for the fact that somewhere along the line, in the period when the chalkstream valleys went from marshes to meadows, the brown trout had become the dominant species in the river. Never ones to miss an opportunity, anglers soon followed, first for food and then for sport, at which point the chalkstreams became a byword for angling perfection. The drowners and farmers were replaced by river keepers who lavished care on the rivers far beyond the basic needs of an agrarian England.

Fishing, angling, call it what you will, with an insect, worm, net, hook, spear or anything else that captures the fish, is as old as mankind. But as a pastime, done for the pleasure of the activity as much as for the outcome, it has to be credited to the Victorians. They did of course have their antecedents. Dame Juliana Berners, an English nun, wrote A Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle in 1496, which can be claimed as the first book about fishing as a sport, although she has been eclipsed in history by Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler, which followed 150 years later. But these great anglers and writers were exceptions; for most people trout were there for catching and eating with the minimum of effort. So why the Victorians? Well, it was a coming together of wealth, leisure time, technology, the railways and the insatiable curiosity of a few individuals.

Gavelwood today is a tiny proportion of what was once a huge country estate, running to thousands of acres and 11 miles of the River Evitt. In fact the entire river valley, encompassing all 30 miles of the Evitt from source to estuary, was in the ownership of just three families. Hardly very egalitarian, but those were the times, and for fishing, and the chalkstreams in particular, they proved decisive for the future. Once the fishing craze caught on amongst the landed gentry the rivers became much more than farmland irrigators and power sources for mills. River keepers were employed, banks maintained, fish reared for stocking, river weed cut, predators removed. The water meadows were kept in good shape not just for drowning but fishing as well. Suddenly the owners of the great estates began to value the rivers for the sport they could offer.

As the railways made the countryside more accessible, great houses hosted grand fishing parties. Gunsmiths turned their hands to fine reels, rods, lines, hooks and flies, using the latest techniques and materials. Weekly magazines like The Field and Country Life lionized innovators like Frederic M. Halford, a wealthy industrialist in his own right, who codified fly-fishing in a single book. Fly-fishing went from an obscure pastime to the ‘must do’ sport in a matter of decades. If you fished for salmon Scotland was the place to head for, but for brown trout dry fly-fishing the chalkstreams of southern England were the ultimate destination.

The mayfly period, or Duffers Fortnight, became as much a part of the English season as Ascot or Wimbledon. The future kings of England were elected president of the world’s most exclusive fly-fishing club. Fine tackle manufacturers received the Royal Warrant. Government ministers cut short cabinet meetings to catch the train in time for the evening rise. Eisenhower took time out from the D-Day preparations to fish the River Test. As the fly-fishing craze spread across Europe and the Americas, visitors from abroad took home stories of the fabled chalkstreams which took on deserved iconic status. But time, money and enthusiasm are not always limitless, and as I walked around Gavelwood on this late September day I could chart the progression from a chalkstream paradise to something that is today a shadow of its former self.