Полная версия

It’s Not Because I Want to Die

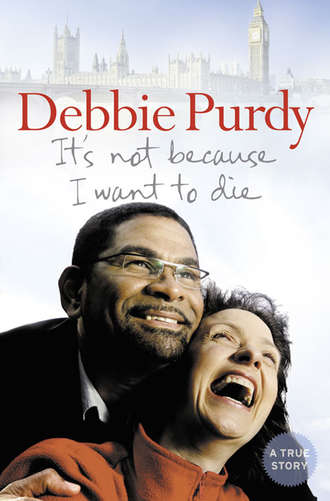

Shortly after that he kissed me for the first time, which was nice. More than nice. He remained a perfect gentleman, though, dropping me back at the flat I shared with Belinda and Tetsu, and asking if he could see me the next evening. He gave me his phone number and taught me how to greet the person who answered the phone: ‘Quiero hablar con mi mulato lindo.’ I repeated the phrase until I could say it to his satisfaction, and we kissed one last time before he headed off down the road, turning to give me a wave as he left my sight.

He and the band members loved it when I phoned the next day – I thought I was greeting them and commenting on the wonderful day; in fact I was asking to speak to ‘my beautiful mulatto’!

Nevertheless, the next night I was right there when Omar played his set at Fabrice’s and he gazed straight at me as he sang many of the numbers. When he was introducing the band, he went through all their names, then at the end said, ‘Allì tienes a la mujer que tiene mi corazón encadenado,’ and I knew without being told what that meant. I had his heart in chains. From then on he said it every night I was there.

The evening after we’d slept together for the first time, he walked off stage in the middle of the Cuban Boys’ set and came over to kiss me, which was incredibly romantic. Our friends in the audience cheered and clapped. I blushed, because I embarrass easily, but I loved it at the same time.

Neither of us had much money, but it didn’t matter – we were living in a beautiful city, had some great friends, and both of us had jobs that we loved and would have paid for the privilege of doing. We had the added advantage of being welcome guests at most of the places we wanted to go. (It seems silly, but business is business and I was more welcome than Omar because I could publicise the venue.) We would talk in odd words and phrases we’d picked up of each other’s language, supplemented by whole sentences when Rolando or someone else was around to translate for us. After the Cuban Boys’ set at Fabrice’s, we would go for breakfast at the market or pick up some food from the 7-Eleven in Orchard Road, then walk home together in the early morning light. It was lovely, despite the fact that I sometimes had to go straight to work without any sleep.

I had a book of Chinese horoscopes in my room and Omar asked me when my birthday was, then worked out that I was born in the Year of the Rabbit, so from then on he called me ‘Rabbit’. That was his pet name for me. He was born in the Year of the Ox, so I didn’t do the same.

We had a fantastic two weeks together, full of music and city lights (and I guess the food and wine didn’t hurt the atmosphere). At the beginning of March a neurology appointment I had booked in Brighton meant I had to go to England. Omar and the band were going to Indonesia for a month to do some gigs at a club in Jakarta.

As we parted on that night in early March, he said to me, ‘See you in a month, Rabbit.’

My life was perfect. I was doing things I loved in a new and exciting city, and I’d just met someone who made the sunniest day a little brighter. I was living a dream, but I didn’t really realise how lucky I was. I took it all for granted. I guess I felt entitled to everything life could offer. As I boarded the plane, I couldn’t wait to get back and carry on living my wonderful life.

Chapter 2 Wading through Honey

The reason I had a neurology appointment was because I’d been noticing my body behaving a bit strangely over the last year or so. There were lots of little things – nothing major – but they seemed to indicate something odd was going on.

The weirdest incident had been in August 1994, when I’d collapsed in the street back in Yorkshire, where I lived at the time. I’d spent the day walking around Leeds city centre with an American friend called Greg, who was thinking of moving to the UK and wanted to explore what kind of work he might be able to get. We’d walked for miles into recruitment companies and coffee shops. Greg needed to get a feel for the city as well as the jobs. On the way back, when we were only a couple of hundred yards from my home in Bradford, all of a sudden my legs gave way beneath me and I collapsed on the pavement.

‘What’s going on? Did you trip?’ Greg stretched out an arm to help me.

‘I don’t know.’ I grabbed his hand and tried to pull myself up, but my legs wouldn’t take my weight: they were weak and unresponsive. ‘Isn’t that strange?’ I felt silly more than anything else. Greg was super-fit, and although I knew I’d been getting a bit out of condition, I hadn’t thought it was quite that bad.

‘Can’t you get up?’

‘I just need to rest a while and then I’ll be fine.’ At least, I hoped I would.

‘Try again,’ Greg coaxed me, concerned and more than a little embarrassed to be seen with a woman who was sitting in the gutter on a busy main road. People passing clearly thought I was drunk.

I summoned all my strength, clung on to Greg’s arm and tried to haul myself up, but my legs still wouldn’t support my weight. An image of the Billy Connolly sketch in which he imitates a Glaswegian ‘rubber drunk’ flashed through my head. I had rubber legs, it seemed, without a drop of booze having passed my lips.

‘It’s no use,’ I said. ‘We’ll have to call a cab.’

Greg seemed glad to be given something to do. Before long he was helping me into the back of a local cab. Two minutes later Greg and the driver got me into the house by holding me on either side and more or less carrying me until I was ensconced in an armchair in my front room.

‘You have to see a doctor,’ Greg insisted. ‘That shouldn’t happen. Shall I phone for someone?’

‘If you want to do something useful,’ I told him, ‘make a cup of tea.’ A universal British cure-all.

We sat and drank our tea and talked about the job opportunities Greg had found, and a few hours later my legs seemed to be back to normal, so I brushed aside all his nagging about doctors and tests and making a fuss. I’m an arrogant sod and prided myself on my physical prowess. I’d completed several parachute jumps, skied, played netball for my county team and learned to waterski off Hong Kong, so a day’s walking shouldn’t have fazed me.

Over the next couple of weeks, though, I gave it some more thought, wondering what was going on and whether I needed to do anything about it. I’d noticed a few other odd things. For example, I was a keen horse-rider, but now it took me quite a lot of effort to get my foot in the stirrup and swing myself up on to the horse. I’d always had a good seat, which you achieve by using your thigh muscles to hold your position on the saddle, but recently I’d been a bit like a sack of potatoes being bounced around as the horse cantered across the field.

Then there was my eyesight. I’d noticed that words were getting slightly blurred on the page. Curiously, it seemed to get worse when I was too hot. I figured that everyone’s eyesight deteriorates as they get older, but I was only 31. Should it be starting that early?

Having lived all over the world, I’d been back in the UK for almost four years before I moved to Singapore in September 1994 and I blamed the British climate for many of my symptoms. I’d put on a bit of weight, so that could have been one factor, but I mostly blamed the sedentary indoor life I’d been leading. When I was out in the Far East, I was always rushing around waterskiing, swimming or cycling. On Christmas Day we would spit-roast a turkey on the beach, decorate palms with tinsel and splash around in the surf. Back in cold, rainy Bradford, Christmas meant eating far too much, drinking more than was good for you and falling asleep in front of the TV.

I had come back to the UK in 1990 to help look after my mum. She had been ill for several years and my sisters had been shouldering the responsibility. I felt it was time that I shared it. When Mum died in 1992, it came as an incredible shock, despite the fact that we’d all known she was ill. It was nice to get close to my family again and I’d planned on staying for a bit, but I was beginning to feel old, putting on weight and generally feeling ‘not right’.

Then, in 1994, a friend of mine, a singer called Mildred Jones, called to invite me out to Singapore, where she had a contract at the piano bar in the Hilton Hotel. She said I could stay with her and she would introduce me to people who would help me to find work.

It was an irresistible offer and I took less than a nanosecond to reply. ‘Sure. I’m on my way.’

I found people to look after the house I owned in Bradford and booked a plane ticket for 24 September. Before I left, I decided to pay a quick visit to my GP just to be on the safe side.

I sat down in his surgery and let the words pour out. ‘I’ve been a bit out of sorts recently. I’m sure it’s partly grieving for Mum, but also I’ve put on some weight that I need to lose, and living in the UK doesn’t really suit me. I prefer a hot climate and an outdoor lifestyle. Anyway, I’m solving it by moving out to Singapore next week. What do you think?’

‘That all sounds very sensible,’ the doctor said, a bit bowled over by the speed at which I can talk when I get going.

All the symptoms I presented him with were subjective: a bit tired, feeling slightly weak, generally depressed. I answered my own questions as I spoke and he just agreed with me. I didn’t have a massive tumour anywhere. I wasn’t in pain. There was nothing concrete that might have made him suspicious that there was anything going on. Besides, I didn’t want to hear any bad news. All I wanted was reassurance. I had a plane to catch and an exciting new life waiting for me, so I more or less presented him with a fait accompli.

‘So I’m fine to go?’

‘Yes,’ he said, looking somewhat baffled by the onslaught. ‘Have a good time.’

The symptoms didn’t go away in Singapore’s sunnier climes, though. If anything, they got worse. I started walking everywhere to try and get fit but found my legs were tired after short distances, and I couldn’t swim as many lengths of a swimming pool as I used to. Then, within three weeks of my arrival, I got a phone call that shattered my world. It was from my auntie Judy’s husband, Uncle Paul.

‘Debbie?’ he said. ‘Your dad is dead.’

‘What? You’re joking!’ He’d come out with it so abruptly that I assumed it was a sick practical joke, even though I knew Paul would never be so cruel.

Auntie Judy took the phone from him. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she said. ‘I’m afraid he had a heart attack.’

‘Really? My dad? Are you sure?’ He was such a life-force it didn’t seem possible.

‘His girlfriend was with him at the time, but there was nothing that could be done. He was dead before the ambulance got here.’ She was trying hard to hold back the tears and not doing too well.

I had talked to Dad the week before I left the UK. He’d been living in the States and was due to arrive in England a couple of days before I left so that we would see each other, but work had delayed him. I’d enquired about changing my flight, but it was a cheap ticket and to change it would cost almost as much as I’d paid for it in the first place. Instead we’d agreed to meet when he came to Southeast Asia a few months later.

I put the phone down and looked around at the friends in the room. They were watching me with concern, having picked up the gist of the call.

‘I’m an orphan,’ I told them, before bursting into tears.

The shock was monumental. How could there have been no warning signs at all? It felt like the end of the world.

One of Mildred’s friends bought me a plane ticket home for the funeral, and my sisters, Tina, Gillian and Carolyn, and my brother, Stephen, and I clung to each other in disbelief. More than two years had passed since Mum’s funeral, but it felt very recent. We hadn’t lived with Dad for a long time, but we still felt bereft. Even in your 30s you want to feel that you have someone to fall back on. Uncle Tony and Auntie Judy, his brother and sister, were inconsolable. They had been close to him all their lives and the three of them adored each other.

A few days after the funeral I caught a flight back to Singapore. I didn’t know what to do, but I wanted to stay busy or I would have sat and sobbed all day long. I’d moved into the flat with Belinda and Tetsu, and there were always people milling around and gigs to attend. I said yes to every invitation as a way of keeping myself afloat, otherwise I would have sunk under the weight of grief.

Two weeks after I got back, in November 1994, Auntie Judy called again, utterly heartbroken. She was stuttering and could hardly get the words out. ‘Tony died. It was a heart attack.’ Apparently he was making a cup of tea when he collapsed and was dead before he hit the floor. He didn’t even disturb anything in the kitchen.

I felt numb this time. It was all too much. I didn’t have the money to fly home for another funeral, so I grieved in Singapore. Still shell-shocked about Dad, it was hard to take in this new piece of information.

Then there was a third blow. On the night of Uncle Tony’s funeral, Auntie Judy died as well. I think she died of a broken heart, because she was so distraught at losing her brothers. They’d all three been so close in life that somehow it made sense that they died close together. I think it would have been unbearable for the ones left behind if it had been any other way. Nevertheless, it was devastating for the family to have three funerals in a row.

I put my head down and tried to get on with life in Singapore. What else could I do? Being on the other side of the world helped to make it seem unreal. Part of me still felt that when I next went home they’d all be there, same as ever.

Mildred was like a mother to me in this period, sweeping me up into her vast group of friends and making sure I didn’t mope around too much. Belinda saw to it that I ate and slept, and I still had my work for the adventure travel brochures and the music magazines. I spent most evenings at clubs and live music venues, and I’d usually be up on the dance floor.

I love dancing, and I was lucky enough to have been born with a decent sense of rhythm (tone deaf, but I could move), but strangely I found my body wasn’t moving the way I wanted it to. I felt as though I was wading through honey, or as if I was wearing trainers and they were sticking to chewing gum that someone had dropped on the floor. (Unlikely, as the Singaporean government had banned the sale of gum.) It wasn’t that I was tired; my movements just felt slow and strange. I thought it was because of the extra weight I’d put on back in England, so I borrowed a bike to cycle around town and get fitter. I wasn’t fat, but I definitely wasn’t as toned as I’d have liked to be.

Soon after Dad’s funeral I began to have the weirdest headaches I’d ever had in my life. It felt as if something was reaching inside my skull and squeezing my brain. They only lasted for a few seconds at a time, but they were intensely painful. I became convinced that I must have a brain tumour. This was in the days before Mo Mowlam, the Labour Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, died as a result of her brain tumour, and my preconception was that they were quite a sexy thing to have. I’d go into hospital, have my head shaved, undergo brain surgery and then recuperate. Everything would be better within a few months and I thought it would be quite exciting. I could be ‘heroic Debbie’ with my bald head, admired for my stoicism.

I flew back to England to spend Christmas with my family, and while I was up in Yorkshire I went to see a GP, presented him with my self-diagnosis and asked to be referred for a CT scan. He didn’t play along, though.

‘Let me put it this way,’ he said. ‘We doctors have to do a kind of jigsaw puzzle. Say you find a bit of blue sky. You might not know exactly where it fits, but you know it’s sky.’

I concentrated hard, trying to work out how this related to my headaches and muscle weakness.

‘There’s nothing physically wrong with you,’ he continued. ‘You were grieving for your mum and felt terrible about losing her, and then your dad died. It’s all happened at once. I’m going to refer you to a therapist who can help you to talk it through.’

So that was it! Depression wasn’t as sexy as a brain tumour, so I was a bit disappointed. I still clung to my ‘heroic Debbie’ image. I’d never been the depressive type and I wasn’t sure I believed his diagnosis, but doctors are always right, aren’t they?

I went down to stay with my uncle Paul in Brighton before my flight back to Singapore. As it happened, his friend’s son had had a brain tumour and they urged me to get a second opinion. They just had an instinct that my doctor’s diagnosis wasn’t quite right.

I went to see my uncle’s GP, a smart, no-nonsense woman with a surgery in Brighton. After listening to my description of the symptoms, she got me to lie down and drag my heel up my shin – first the left heel, then the right. I managed it, but there must have been something she didn’t like about the way I did it. She ran a few more tests and asked me lots of questions, then said she was going to refer me to a neurologist.

Good, I thought. A neurologist sounded serious and important. Surely he would be able to send me for a brain scan and we’d be a little closer to coming up with a diagnosis, something unusual and interesting.

I was warned it would be a couple of months before the appointment came through, so I went back out to Singapore, still secretly convinced I had a brain tumour. I didn’t tell Mildred or anyone else about my theory because it sounded melodramatic. In answer to their questions I said, ‘Oh, there’s nothing wrong with me,’ imagining that when I finally told them the truth they would think, Poor thing, she was trying to be brave and play it down when all along she was suffering terribly.

Peter, my boss at the adventure travel company, seemed to be happy with my work because he asked if I would like to go on a scuba-diving course on Tioman Island, off the Malaysian coast. Would I ever! The idea was that I would write a diary of my experiences that would be published by 8 Days, a magazine about what’s on in Singapore. Peter, his partner and other colleagues could already dive and they wanted someone who could write about the learning experience. Once I could dive, Peter promised that he would send me to review other scuba sites they covered.

I loved the resort on Tioman, a genuine paradise island with white sand and palm trees. The staff were bottle-feeding a little orphan monkey whose mother had been killed by poachers and everyone liked playing with him because he was so cute and cuddly.

I found the underwater world magical. If you learn to dive off the British coast, the visibility is likely to be measured in inches, feet if you’re lucky, but in the South China Sea we could see way off. It was incredible to be underwater marvelling at the rainbow-coloured fish and strange tentacled creatures, and my worries about a brain tumour faded into the distance. How could I possibly be ill when I felt so alive and exhilarated?

Back in Singapore, reality intruded when I got word that my neurology appointment would be on 6 March and the therapy session a couple of weeks later. It was time to make another trip to the UK, just after I’d started going out with Omar.

‘You won’t send anyone else on the diving trips, will you?’ I asked Peter. ‘You’ll definitely wait for me to come back?’ I think I’d have cancelled the appointments otherwise.

‘It will all be here waiting for you,’ he promised. ‘Good luck!’

On 6 March 1995 I turned up for my neurology appointment at the Royal Sussex County Hospital. I recited the list of symptoms, mentioned that my parents had died recently and ventured my humble opinion that I might have a brain tumour.

‘Lie down on the bed,’ the neurologist instructed. ‘Tell me what you can feel.’

I could see he was holding a pin, and as far as I was concerned he just touched it lightly on my foot, pressing a bit harder as he moved up my leg, then stabbing it into my thigh. That’s what I told him.

‘Actually, I applied the same pressure all the way up,’ he told me.

I blinked in surprise. It seemed I had reduced sensation in the lower parts of my legs. What on earth did that mean?

‘I’m sending you for an MRI scan,’ he said. ‘We’ll talk after that.’

I went back to my auntie Pat and uncle Dennis’s house where I was staying, puzzled by the fragments of information I’d gleaned. Why would a brain tumour cause reduced sensation in my lower legs? Was that why I’d been feeling weird when I was dancing, and why I’d collapsed in the street that day with Greg?

I’d heard it took months for MRI appointments to come through, but mine only took about ten days. Why was it so fast? Was it due to mega-efficiency on the part of the hospital, just good luck, or had the neurologist told them it was urgent?

‘It will take about forty-five minutes,’ the radiographer told me. ‘You have to lie very still on a bed that will slide inside a hollow tube, where we will take pictures of your insides a bit like a 3D X-ray. It’s a bit noisy in there, so you’ll need to wear some earplugs.’

I lay down on the bed, earplugs in place and a call button in my hand in case I got a sudden attack of claustrophobia. I was swept into the machine. There was a moment of silence, then a cacophony of clanking and long piercing beeps and a churning, whirring sound. After only a few minutes the noise stopped and I was sliding out again.

‘What’s up? You said it would take longer.’

‘I’ve got all I need,’ the radiographer told me.

‘You’ve found something, haven’t you? Is it a brain tumour?’

‘The consultant will study the images and discuss the results with you. He has to interpret them.’

I knew they had found something. They must have. Why else had it only taken a few minutes? But they wouldn’t tell me.

I was due to travel up to Yorkshire the next day to see the therapist I’d been referred to, but I rang my neurologist first.

‘Should I go to Yorkshire?’ I asked, and explained the situation.

‘No, come in to see me tomorrow morning at ten to nine, before surgery starts.’

That’s when I knew for sure that they’d found something. I spent the night imagining the worst and trying to talk myself round. My aunt and uncle drove me to the hospital the next morning and at my request they waited outside in the car park. I wanted to face this on my own.

‘So what is it?’ I asked as I sat down, more nervous than I was when I sat my O levels – and that’s saying something.

The consultant looked grave. ‘When I first saw you, I thought you had MS.’

I waited for the other shoe to drop.

‘And it is MS.’

It’s normally hard to shut me up, but I couldn’t think of a single thing to say. The consultant continued that he was going to refer me for a lumbar puncture so that he could definitely rule out a couple of other things, but said he was convinced it was multiple sclerosis. He had been pretty sure from my gait when I first walked into his office, and the MRI scan had backed up his instinct. We made an appointment to talk again after I’d had the lumbar puncture.

I left his office and walked back down to the car park, where my aunt and uncle were waiting, and still I couldn’t speak. I got into the car and stared at them wordlessly with an overwhelming sense that my life had just changed for ever.

Then I rejected it. He had to be wrong. Please, God, he simply had to be.

Chapter 3 ‘Can I Scuba-Dive?’

The only thing I knew about multiple sclerosis was that it was not a good illness to have. All I could think of was a poster I’d seen of a girl with her spine torn out and the legend ‘She wishes she could walk away from this picture too.’ Did that mean I wouldn’t be able to walk any more? That’s when I began to get upset. I couldn’t bear it if I ended up in a wheelchair.

I was in a complete state when I rang my best friend, Vera, a Viking from Oslo. ‘My life is over,’ I wailed. ‘Omar won’t want to go out with me any more. No man will. My friends won’t want to be my friends any more because I’ll be stuck at home and I won’t be able to go out. No one will want to know me. I’ll be useless.’ I must have sounded shrill and tearful.