Полная версия

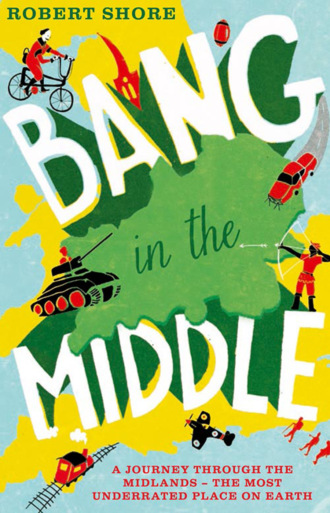

Bang in the Middle

Robert Shore

BANG in the MIDDLE

A JOURNEY THROUGH THE MIDLANDS – THE MOST UNDERRATED PLACE ON EARTH

Contents

Title Page

To Mansfield

To Nottingham

To Melton Mowbray

To Grantham

To Northampton

To Stratford-Upon-Avon

To Coventry

To Birmingham

To Lichfield

To Stoke-On-Trent

To Chatsworth

To The Crags

Acknowledgements

Fifty Great Things to Come Out of the Midlands

Copyright

About the Publisher

Queen Victoria’s blinds, John Gielgud’s private parts, and the great Robin Hood feud

So there we were, sprawled across the floor of our living room in South London, happily building a Lego Pharaoh’s Quest Flying Mummy Attack, when Hector dropped The Big Question.

‘Dad?’

‘Hmm?’

‘Where are you from?’

Hector had been asking a lot of questions lately – partly because, at five years of age, he was in the middle of the classic ‘why/where/when’ stage of child development, and partly because his school topic for the term was ‘About Ourselves’.

‘I’m from England,’ I said confidently. ‘Your mother is from France and I am from England.’

‘I think he needs a little more detail than that,’ my wife said, entering the room to deliver her line and then immediately exiting again, like an actor with a walk-on part in a French farce.

‘Okay, if it’s more detail you want,’ I steadied myself, ‘I’m from Mansfield.’

‘Oh,’ mused Hector. ‘Where’s that?’

‘You know, where Grandma and Grandad live. It’s in the Midlands.’

‘Oh,’ he mused again. ‘What’s the Miglands?’

‘Don’t you want to finish the biplane so we can start launching our flying attacks on the mummy?’ I said, trying to change the subject. A father likes to be able to answer his son’s questions with authority, and I wasn’t sure that I had anything very definite to tell him on the subject of my origins.

‘Miss Kate says she wants parents to come in and tell us about where they’re from,’ Hector persisted. ‘Do you want to come to school and tell us about the Miglands?’

I could just imagine the scene: a parade of parents from Bosnia, Bologna and Baghdad, all with amazing tales to tell to boggle the imaginations of a class of wide-eyed five-year-olds, and then me, bringing up the rear of this exotic, multi-lingual procession, turning bright red with embarrassment as I desperately tried to think of something interesting to say on the subject of Mansfield and the Midlands.

My wife is a Parisian, so on his mother’s side Hector’s heritage is rich: berets and haute couture, baguettes and haute cuisine, moody philosophers in black polo necks, and a general all-round je ne sais quoi. As cultural legacies go, you can’t ask for better. My contribution is thinner. Mansfield was named the sixth and ninth worst place to live in Britain, respectively, in the 2005 and 2007 editions of Channel 4’s popular The Best and Worst Places to Live in the UK show.

As for the Midlands – well, as a badge of identity, it’s not like coming from the North, is it? Few people would know where to draw the boundary lines that separate the coastline-free Midlands from the North and South of England, those two monolithic and self-mythologising geographical constructs that sit above and below it on the national map. Just as importantly, whereas most people could attempt at least rudimentary definitions of the North and South as cultural entities – flat caps versus posh accents, or, in the terms of Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, ‘Southern fairies’ versus ‘Northern monkeys’ – very few would find much to say about the Midlands’ ‘identity’. And that includes Midlanders.

I grew up in the Midlands, but I can’t remember anyone ever referring to themselves or me as a Midlander – there was a distinct lack of what you might call ‘Midland consciousness’. When I then went south to university, I was perceived as a Northerner, principally because I pronounced the word ‘class’ with a short ‘a’. ‘You’re quite well-spoken,’ I was assured by one of my Home Counties-scented, RP-channelling peers, ‘but you’ve got funny vowels. Might you be from the North, old boy?’ Since I didn’t much fancy spending the next three years propping up the bar with the college’s real Northerners, mithering on about dinner being the meal you eat in t’middle of t’day, lad, and how Southerners couldn’t take their drink, I grew self-conscious about my pronunciation and avoided making any unnecessary references to grass, glass or taking a bath in my conversation.

Even in this great Age of Identity Politics, coming from the Midlands is tantamount to coming from nowhere in particular. You can be a Professional Northerner (it’s a crowded field, but there always seems to be room for fresh recruits), but a Professional Midlander? The very word ‘Midlands’ is rarely employed outside specialised or technical contexts. It occurs most frequently in weather and travel reports (there are a lot of roads in the Midlands). Beyond that, it pops up in the camp idiom of a certain vintage: in his letters, the (London-born) classical actor John Gielgud refers to the zone between his legs and midriff as ‘the Midlands’. We all come from there at a biological level, of course, but in a geographical context there’s little social cachet in announcing yourself as hailing from the nation’s meat-and-two-veg.

* * *

I decided to do what I have done so many times before at moments of crisis in my life. I called my mother.

(Sound of a phone ringing out. The receiver is eventually lifted and a small intense woman, audibly gurning, speaks.)

‘Hello?’

‘Hi, Mum. It’s your second-born.’

‘Ey up mi duck.’ My mother is hardly a strong dialect-speaker, but she does enjoy slipping into the local argot from time to time. ‘Can I call you back later? I don’t really have time to talk at the moment.’

‘Then why did you pick up the phone?’

‘In case it was something important.’

I went into my hurt-silence routine, honed over decades.

‘Come on,’ she chivvied me. ‘What can I do you for? Spit it out.’

‘Mum, there’s a question I need to ask you.’

‘I love you and your brother both equally. I’ve told you before.’

‘Not that.’

‘Oh good, I was getting a bit tired of it.’

‘Mum, what does it mean to be a Midlander?’

Now it was her turn to go silent.

‘Mum?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said, noisily chewing her lip. ‘I’ve never thought of it before.’

‘Well, would you think about it now, please?’

‘All right, keep your hair on … Well, I suppose it means we’re neither one thing nor the other – not Northern, not Southern. We’re just a bit middling.’

And that was all she could think of to say. In one respect – the stoical acceptance of one’s own inconsequentiality – it was a thoroughly Midland sort of response. On the other, it was baffling, since my mother is anything but middle-of-the-road. Quite the opposite, in fact: she’s one of the most extreme characters I’ve ever known. That’s a Midland paradox.

At that moment I realised that something important – life-changing, even – was happening to me: I was reconnecting with my Inner Midlander. This sort of thing happens to Northerners all the time, of course. It’s easy for them because there are so many clichés about Northern identity that they can tap into. But if you’re a Midlander? Instinctively, as well as in point of strict bio-geographical fact, I had always known I was one, of course, but I had no idea what that might signify in a wider sense. What is a Midlander?

‘Right,’ I said, putting the phone down and turning to my son with unwonted firmness of purpose. ‘You wanted to know where I am from, Hector. I say to you now that I don’t really know. Not geographically, obviously – show me a map and I will unerringly pin the tail of a donkey to the precise point on it where Mansfield lies. It’s just above Nottingham and a bit up and to the right from Derby. But in a broader sense – culturally, philosophically – I’ve no idea what it means to be a Midlander. So I must find out. We must find out. You have asked me the question and together we will discover the answer. Son, let us get into the car immediately and set off in search of my – I mean, our – identity.’

I thought my speech stirring, but Hector just looked a bit confused and upset. After all, he’d been planning to watch Megamind on DVD.

Putting her head round the door precisely on cue, his French mother came to his rescue again. ‘Hector’s got a birthday party this afternoon and we’re having lunch with the Downings tomorrow, so there’s no question of us going anywhere this weekend.’

‘Oh,’ I quivered, momentarily thwarted. ‘All right then, we’ll go next weekend instead.’

* * *

In truth, I was glad to have an opportunity to do a little research before setting off in search of my Midland heritage, and that is what I spent every spare moment of the following week doing. What I discovered by leafing through classic accounts of tours around England was very illuminating. Pretty depressing too, if truth be told.

If you want to know about attitudes to the Midlands, you could do worse than start with Bill Bryson’s Notes from a Small Island (1995). Bryson is an American who settled in the UK – in North Yorkshire, to be precise, a choice that may be significant in itself – and made a reputation for himself as a travel writer. In Notes from a Small Island he set himself the task of explaining the British to themselves by undertaking a tour of this ‘small island’ – not so small, however, that he felt the need to engage in any detail with its sizeable middle swathe. No major Midland towns are marked on the map at the front of Bryson’s book. We find London, Oxford, Leeds, even Bournemouth and Halkirk (‘Where?’ I hear you cry), but no Nottingham or Birmingham – the latter being the largest city in the UK after London.

Flicking through its pages, there’s a sense that for the most part Midland locations are beneath Bryson’s notice. When he does write about them, he adopts a tone of gentle condescension. Retford, for instance, he declares ‘a delightful and charming place’; ‘the shops seemed prosperous and well ordered. I can’t say that I felt like spending my holidays here.’ Worksop is ‘agreeable enough in a low-key sort of way’. After he quits the South, the people he encounters only really come to life again and begin to talk with vivid local accents when he reaches the great city-states of the North, Manchester and Liverpool, where ‘bus’ suddenly vowel-shifts into ‘boose’. If you tried to arrive at a working definition of the Midlands from Notes from a Small Island, you might be tempted to characterise it as the lowland bit between the national peaks, however defined – geographically, socially or culturally.

Bryson’s book is part of a much wider tradition. The great surveys of the country tend to bypass the Midlands or emphasise its anonymity by other means. In his classic interwar study In Search of England, for instance, H.V. Morton names Rutland in the Midlands as ‘the smallest and happiest county in England’, but then adds: ‘I am the only person I have ever known who has been [there]. I admit that I have known men who have passed through Rutland in search of a fox, but I have never met a man who has deliberately set out to go to Rutland; and I do not suppose you have.’ Morton pays Rutland a great compliment, but in such a way as to stress its invisibility at a national level. As he says, ‘most people think [it] is in Wales’ – which, let’s face it, isn’t meant as a compliment.

Another mid-century guidebook pays tribute to the beauties of the Midland landscape, suggesting that the ‘Peak District in Derbyshire – with Buxton spa as a Convenient Centre – is worth a visit’. It turns out to be a qualified recommendation, however: ‘Whoever cannot go to Cumberland, Northumberland or Yorkshire will find compensation in the moorlands and hills of the Peak District, and in its deep valleys and rugged cuttings.’ In other words: for real English scenery, you’d be better off in the real North. The Midlands can be delightful, the author allows, but it’s never more than a ‘compensation’, a second-best option, a silver medallist at best in the race for national gold.

When an opinion is expressed about the region as a whole, it’s usually thoroughly damning. In 2003, the East Midlands found itself listed in a Spectator magazine travel special under the heading ‘Best Avoided: Places That Suck’. Recent research confirms how widespread this perception is. ‘Industrial, built-up, heavily populated, busy, no countryside; Uninteresting, nothing there, not touristy, unromantic; Dark, dirty and grey; Cold and windy’ were the words used to summarise the views of foreign respondents in a tourist-board survey of perceptions of the region. Booked your summer holiday yet? Well, now you know where you should be going.

The West Midlands fares little better in the popular imagination. Researchers at King’s College London recently announced that, for most people, Birmingham accents were inextricably linked with low intelligence. Most non-natives remain blind to the region’s charms, a tradition that stretches back at least as far as the Industrial Revolution. When Queen Victoria travelled through the Black Country – so named owing to the soot and grime that coated this highly industrialised area in the nineteenth century – she insisted on having the blinds pulled down in the royal train. Figuratively at least, it’s with the shutters firmly closed that most people still prefer to experience the Midlands. Americans call their Midwest – that big bit between the exciting, trendy coastal states – the ‘flyover states’. We’re a much smaller country and less given to taking domestic flights, but by analogy we could call the Midlands the ‘drive-through counties’ – the boring bit you drive through to get to where you really want to be.

In her spiky survey Class, Jilly Cooper – she of the saucy horsey romps – complains about ‘the terrible flat “a”s and dreary, characterless Midlands accent … which conjure up a picture of some folk-weave goon’, before declaring, in the chapter on ‘Geography’, that for the upper classes and, by extension, anyone from the smart set: ‘The Midlands are beyond the pale.’ Dispiritingly, many Midlanders wouldn’t disagree. There’s a thread on the Amazon website that’s very revealing of what might be called Midlander status anxiety. One contributor says: ‘Strictly speaking, coming from Derbyshire, I suppose I live in the Midlands but I feel like a Northerner. It has to do with accent, values and the time of day you eat your dinner.’ Another from Stoke-on-Trent agrees: ‘Though perhaps geographically we are in the North Midlands, we are very much a Northern city in spirit, outlook and feeling.’ Contributors regularly refer to the Midlands as a kind of ‘no-man’s-land’ or ‘minor melting pot’ that is ‘caught between stereotypes’ of North and South and that consequently lacks a distinct character of its own.

Soap operas have been prime conveyors of ideas about the major varieties of English identity for decades. Unsurprisingly the North and South dominate: London has EastEnders, Yorkshire Emmerdale, Manchester Coronation Street. It’s perhaps just as well that the Midlands no longer has a major evening TV soap to its name – let’s face it, the woolly-hat-wearing simpleton Benny in Crossroads wasn’t doing the region’s image any good. These days, of course, reality shows are as integral to our sense of identity as soaps and, in so far as they are geographically defined, the North and South again rule the roost: Desperate Scousewives, The Only Way Is Essex, Educating Essex, Educating Yorkshire, Made in Chelsea, Geordie Finishing School for Girls, Geordie Shore … Industry myth has it that a novice producer from the Black Country suggested The Only Way Is Wolverhampton but before the ITV2 commissioners could green-light the project their sides split and they literally died laughing. The Midlands, it would seem, just doesn’t have the necessary clout to carry a reality show.

When, against massive odds, one of the Midlands’ many beauty spots does make it onto TV, its actual location is often obscured. For instance, a recent episode of BBC2’s Town with Nicholas Crane was devoted to Ludlow, the Shropshire idyll celebrated by John Betjeman as ‘probably the loveliest town in England’. It was described in the opening moments as ‘landlocked’ – the key attribute of the Midlands, after all – but the term ‘Midlands’ was never actually deployed in the programme: the BBC probably thought that kind of dirty language inappropriate for the show’s genteel target audience. Instead Ludlow was described as being ‘on the Welsh border’, which is true, although if a similar programme about Sheffield failed to mention that it was in the North but stated instead that it was ‘on the border of the Midlands’ it would cause uproar among the locals. Viewers might have come away thinking Ludlow lovely but the association wouldn’t readily have been made with the broader idea of the Midlands. And that’s a real problem for the area.

A friend of mine with a deep knowledge of the broadcasting industry thinks the BBC’s neglect of the Midlands is structural. ‘The Beeb is set up in a way that is institutionally biased against the Midlands!’ he laughs. ‘It’s spent a lot of money in recent years to get more regional television in, so it now has all these designated regions: there’s London, the West and Wales (centred on Bristol), Manchester and the North, Scotland and Northern Ireland. And all of these blocs have pots of money earmarked for them, but the Midlands doesn’t fall into any of the remits. Hence it’s almost impossible to get anything commissioned there.’

Perhaps it would be a kindness simply to abolish the Midlands. That’s precisely what one academic map did recently. Tellingly, that map was created in Sheffield and displayed in Manchester, cities that are both – as if you didn’t already know it; and how could you not, given that region’s genius for self-promotion? – in the North of England.

Ah, the North, where they eat dinner at midday as God (and Geoffrey Boycott) intended, say ‘bath’ not ‘baarth’, speak their minds freely and plainly without recourse to any circumlocutory Southern waffle, where lager is a girls’ drink, blah-di-blah. You certainly know where you are with the characterful North. It’s not much of a place to live – ask all those BBC types who have been dragging their feet over their recent enforced relocation to Salford, the MediaCity development being one of the most flagrant bits of social engineering in recent English history – but you have to admit that, as a piece of branding, ‘The North’ has real genius, starting with the fearsome granite firmness of the name itself. The words ‘I’m a Northerner’ pack so much punch and communicate a ton of attitude. No wonder people from cities as radically different as Manchester and Newcastle are happy to share an overarching, aggregated ‘Northern’ identity. The Midlands, by contrast, has never really gone in for that sort of branding. Around Birmingham, the tourist-board people like to talk about the region as ‘The Heart of England’. But try saying ‘I’m a Heart of Englander’ and it just sounds naff. It might work as a piece of signposting for tourists but it’ll never catch on where it really counts, among Midlanders. As a clever acquaintance suggests: ‘The Midlands is less a discrete geographical category and more a state of mind. Roundabouts. Retail parks.’ If that’s the case, that’s hardly going to pull in the tourists, or provide the locals with a proud sense of belonging. The linguistic associations of the word ‘Midlands’ itself are no better: fair-to-middling, caught in the middle, middle management, midlife crisis. An alliteration-loving friend recently relocated to Northants. ‘I’m growing fond of the Midlands,’ he texted me. ‘Must be middle age setting in.’ See? Midlands/middle age. The connections made at the verbal level are nothing short of lethal.

* * *

The following Saturday we get in the car to head for Mansfield and the Northern propaganda begins even before we’re out of London. The motorway signpost at Archway roundabout immediately announces ‘THE NORTH’ in block capitals – if you take the M1, you must be going to the North, it tells you. Note that it doesn’t just say ‘North’ – a direction – but The North, a destination. The message is repeated, in the same bold typography, all the way up the motorway, next to each and every place name. Watford? ‘The NORTH.’ Luton? ‘The NORTH.’ Only when you get to the edge of Milton Keynes – where the region actually begins: there’s no advance warning – does ‘The MIDLANDS’ finally get a mention. And then, as suddenly as it appeared, the word vanishes again, so that the names of all the major towns and cities of the East Midlands – Northampton, Leicester, Nottingham – are unerringly accompanied by the words ‘The NORTH’. No wonder a lot of Southerners think the North begins as soon as you leave London: that’s what the road signs tell you.

I’m not put off, though. We’ve come to discover what it means to be a Midlander and we’re darn well going to find out, good or bad.

Neil Young’s ‘Everyone Knows This Is Nowhere’ is playing on the car stereo as we finally cross the border into Northamptonshire. I give a loud cheer.

‘Is Dad all right?’ Hector asks his mother, who raises a quizzical eyebrow in my direction.

‘I was cheering,’ I explain, ‘to indicate that we are home. Well, I am home. We are in the Midlands, my ancient homeland. We are now surrounded’ – I wave an arm airily to left and right, trying not to lose control of the car as I do so – ‘by my tribespeople.’

That quizzical Parisian eyebrow stays raised. ‘I didn’t realise you had such a sense of cultural belonging. We’ve been married thirteen years and you’ve never mentioned your tribespeople before,’ my wife says.

‘Let’s just say I’m rediscovering who I really am,’ I sniff.

* * *

‘What is civilisation?’ asked the great art historian Kenneth Clark (not to be confused with the great Midland politician Ken Clarke) in the opening moments of his famous 1960s BBC arts series Civilisation. ‘I don’t know … But I think I can recognise it when I see it; and I am looking at it now.’ Clark, standing with Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris peering over his left shoulder, wasn’t taking much of a chance when he made this statement. But would he have been able to say the same if he’d been plonked in the middle of Mansfield market square one Saturday afternoon in autumn?

Probably not. Mansfield has recently been subjected to a gruelling bout of ‘regeneration’, with results that are largely indistinguishable from ruination. Most of the big commercial operations have relocated to the retail parks dotted around the ring road, leaving much of the town centre boarded up. Pubs (‘Gerrem in!’ is an essential item of local dialect), pawnbrokers and betting shops dominate the historic market square, which is so run-down that even the Poundshop has closed down, or so it appears. (There’s a Pound World that’s still open around the corner, mind, not to mention Savers, another budget store.) The most characterful shop here is Eden Mobility: mobility scooters are enormously popular in Mansfield. If you don’t watch where you’re going, you’re likely to get mown down by one in the market square.