Полная версия

Collins Tracing Your Family History

A FEW FACTS

The only dates in the oral history were for Mbari, who was chief of his tribe from 1795 to 1797, and Katowa, who was chief 1450-97. The earliest ancestor, Mukunti-Muora, supposedly lived 4000 years ago. One thousand would be more realistic, and to get back from 1795 to 1450 in five generations is stretching it. There may, then, be some omissions of generations, or misremembered facts, but that makes this no different to the earliest oral pedigrees of the British Isles, which stretch back to Arthur, Brutus of Troy and the god Woden. This does not detract from their immense value because they undoubtedly do record the names of ancestors who really lived, and who are not recorded in any other fashion. Lose the oral history and these ancient memories will vanish irrevocably.

Such traditions should be treated with the greatest respect, but it is unrealistic to imagine that they can be strictly accurate. When using oral history as the basis for original, record-based research, you mustn’t be surprised if you find names, dates or places are given slightly (or sometimes wildly) inaccurately. I sometimes get my own age wrong by a year (I certainly can’t remember my telephone number all the time), so you should be prepared for this and, if you do not find what you are looking for under Thompson in 1897, see if what you want isn’t listed under Thomson in 1898 instead.

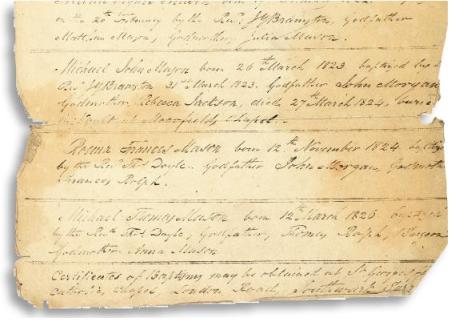

Family papers: lists of children’s dates of birth and baptism were often kept by families, especially before the start of General Registration in 1837.

In fact, you can’t trace a record-based family tree properly without developing a healthy scepticism for anything you are told, or indeed anything you read. There are deceptions and lies, of course. One family I helped, who were called Newman, discovered their ancestor had faked his own suicide and started a new life – as a ‘new man’, his original name having been something completely different. More often, though, discrepancies and inaccuracies arise through simple mistakes or lapses of memory. ‘Granny would never lie,’ said one client of mine, ‘so that birth certificate must be wrong.’ No, Granny didn’t lie, she just got her age slightly wrong. There’s a real difference.

Indeed, recording oral history often relies on interviewing the elderly. Sometimes, it’s the only time very old people have any proper attention paid to them, so be indulgent if they don’t reel out exactly what you want in ten minutes flat. Letter, telephone and email can all help you gain valuable information from your relatives, but if you can visit them, so much the better. It may seem a bind, but it’s often worth it and will become part of your store of memories to pass on to later generations. I once went all the way to Tours in France to visit Lydia Renault, a cousin of my mother’s. I arrived at 11am and, whereas her English relations would have offered me tea and some ghastly old biscuits, Lydia suggested whisky and Coca-Cola, which we drank on her balcony, overlooking the Loire, while she regaled me with tales of her family at the start of the 20th century.

ELICITING THE PAST

That was an exception. If you get tea and stale biscuits, receive them with as great a semblance of delight as you can muster. If you are approaching someone you haven’t met before, make every effort to write and telephone in advance and make it absolutely clear you are after their invaluable knowledge, rather than their (usually less valuable) purse. Write down (or tape record) everything they say, as the seemingly irrelevant may later turn out to be the main clue that cracks the case. If they have difficulty remembering facts, ask them to talk you through any old photographs they may have – that often stimulates the synapses – and sometimes you may get more from them if you allow them to contradict you.

FOR EXAMPLE:

‘What was your grandfather’s mother called?’

‘Oh, I don’t know.’

‘I think it was Doris.’

‘No, no, Doris was his sister. His mother was Milly!’

Another tip: if they can’t remember a date of, say, when someone died, try to get them to narrow down the period in which it could have happened.

‘When did your great-grandmother die?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Well, do you remember her?’

‘Oh yes, she was at my wedding.’

‘So she was alive in 1935. And was she at your first child’s christening in 1937?’

‘Oh no, she died before then.’

Be sensitive, too, to changing social attitudes. Fascinating though it may be to you, the very elderly may not want to talk about their parents’ bigamous marriage, so if you want any information from them you must tread very carefully. One man’s black sheep, after all, is another’s hero.

THE POWER OF PAPER

Don’t forget, though, that younger relations of yours may have been told things by much older relations who are now dead. Equally – and here we leave the realms of oral history and move on a step – they, like the elderly, may have family papers and heirlooms. These come in so many forms: letters, school reports, memorial cards, passports, vaccination and ration cards, and so on, all crowned by the queen of all family papers, the family bible.

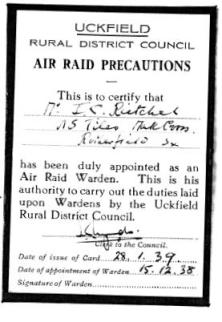

My grandfather’s air raid warden card. Note that he had been appointed before the war, in 1938.

Some bibles can be centuries old, faithfully recording the births, marriages and deaths of each member of the family. The tip to finding family bibles is to trace down the female-to-female line of the family, as they are often passed from mother to daughter. Lost or unwanted ones (how can anybody not want a family bible?) often end up at car boot sales and genealogical magazines have been known to publish letters from well wishers who have found such a bible, describing its contents and volunteering to return it to the right family.

Whether it’s a family bible or a 70-year-old funeral bill, write down all the salient details (or, better still, photocopy everything) because such papers may contain clues that will only become useful to you long afterwards. Ignore such advice at your peril and, if you have to go back all the way to Wigan to have another look at your cousin’s grandmother’s address book you didn’t bother with ten years ago, don’t blame me.

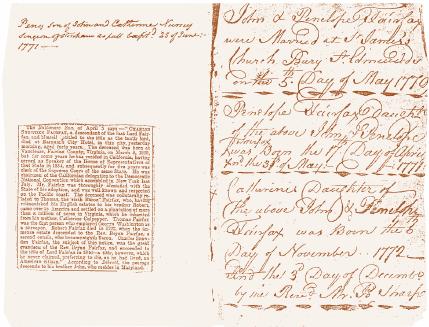

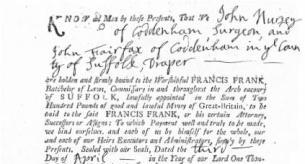

Pages from the Fairfax family bible, which even includes an extra newspaper cutting.

Actually, the real prize transcends even that, because sometimes you will find that an ancestor will already have tried to trace the family tree. One of the things that really encouraged me to pursue my own was being given a Harrods’ carrier bag full of ‘the family papers’, which turned out to be my great-great grandmother’s notes, showing her attempts to trace her family tree between 1880 and 1920. Sadly there was no sign of her finished family trees – if there ever were any – and nor have they ever turned up. However, the bag did include replies to letters she had written to her second and third cousins, thus filling out my own family tree before I had ever set foot outside my front door.

Family reunions: a family photograph showing the Adolph, Mitchiner and Gale families celebrating the 80th birthday of my grandfather Joseph Adolph in 1990.

AN OUTLINE OF THE MAIN SOURCES

PRELIMINARY RESEARCH

BASIC RESEARCH

MORE IN-DEPTH RESEARCH

AND, IF ALL GOES EXCEPTIONALLY WELL …

CHAPTER TWO WRITING IT ALL DOWN

The rest of this book is about how to trace your ancestry, but this chapter focuses on how to record your findings, from getting all your notes written down on computer or paper and moving onto understanding the family tree conventions.

Your Family Tree and Family History Monthly genealogical magazines.

Some people can get bogged down in choosing computer packages, filing systems and so on. Frankly, if you enjoy computer programs, then you’ll love family history, as there is a vast array to chose from, reviewed and advertised in the genealogical magazines like Your Family Tree and Family History Monthly, with an excellent comparative chart at www.Myhistory.co.uk. Everyone has a preference. Personally, I don’t rate very highly the packages that invite you to fill in forms about all your ancestors. I feel it de-humanises them and encourages some people to become obsessed simply with the act of form filling with completing forms that can’t be. Me? I keep a cardboard file for each family I am tracing, containing photographs, documents, notes and so on, and a rough family tree on paper, and then maintain a narrative pedigree on my word processor. Once I feel satisfied with what I have done, I may also write up a summarised version of the family story, including the best pictures and documents, either to circulate among the family or to submit to a relevant family history journal (see here).

GETTING IT ON PAPER

The main point at this stage is to write everything down. Be they oral or written, quote your sources precisly. Later, you can interpret the sources, but if you do this initially and discard the original information, and then find that your interpretation of the sources had been wrong, you (or someone else trying to help you – and, believe me, I’ve been there!) may have a terrible time disentangling what is correct from what is not. This applies just as much to interviewing people as to record-based research. In addition, always write down exactly what records you were searching, for what periods and for what you searched. If you do, and later you find that you are stuck, you may rely on your notes to tell you, say, that you looked under Thompson and also Thomson, thus potentially saving yourself a repeat journey to a record office to perform a search you had, in fact, already carried out but forgotten about.

THE BASIC FAMILY TREE

CRANE PRINTS

OLD FAMILY TREES were drawn with the names of parents in circles and their children radiating out below them. This arrangement was thought to resemble the footprints of Cranes in the soft mud of river banks, hence their name ‘Crane’s foot’ – ‘pied de Cru’ – pedigree!

There are several different types of family tree. These are:

‘Family trees’ and ‘pedigrees’, sometimes prefixed with the term ‘dropline’ (a chart with the earliest ancestor at the top and each subsequent generation connected by dropping lines), are one and the same – charts depicting a line or lines of ancestry.

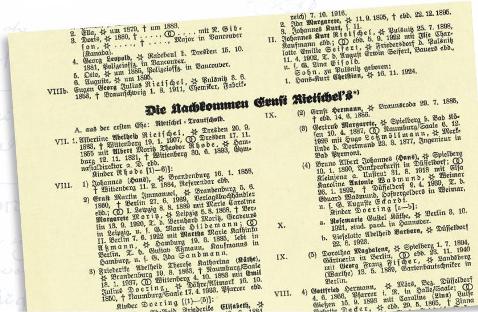

‘Narrative pedigrees’, which are family trees written down in paragraphs, a style that is used by Burke’s Peerage and which is a highly effective way of recording a lot of information in a small space, but which isn’t so good for easily seeing who’s related to who. It is not much use for conducting original research, when only a family tree will make everything clear.

Seize quartiers, which spread out either like trees or in concentric circles, to show both parents, all four grandparents, the eight great-grandparents and – if you can manage it – all 16 great-greats. The original purpose of seize quartiers was snobbish, as you had to prove that all 16 were noble if you wanted to join foreign orders of knighthood like the Golden Fleece. Now, however, they are a good way of showing you have traced your family exhaustively. But don’t feel obliged and become exhausted, this is supposed to be fun and you can aim to trace as much or as little as you want.

Part of my mother’s family tree, showing how Germans Printed pedigrees in the 1930s.

CHARTING CONVENTIONS

= Indicates a marriage, accompanied by ‘m.’ and the date and place

— Solid lines indicate definite connections

… Dotted lines indicate probable but unproven ones

– – Loops are used if two unconnected lines need to cross over

Equally, there are no rules about what you can or can’t include on a family tree. Put in as much or as little as you want and include as many families as you want, though beware of cluttering. I would recommend a minimum of full names, dates of birth or baptism, marriage and death or burial, where those events took place, and occupations. If your chart lacks any of these, it will be of little use to other researchers and, more importantly, it will be boring. If you know someone was crushed to death by a bear or invented the casserole dish, for goodness sake put it on the chart!

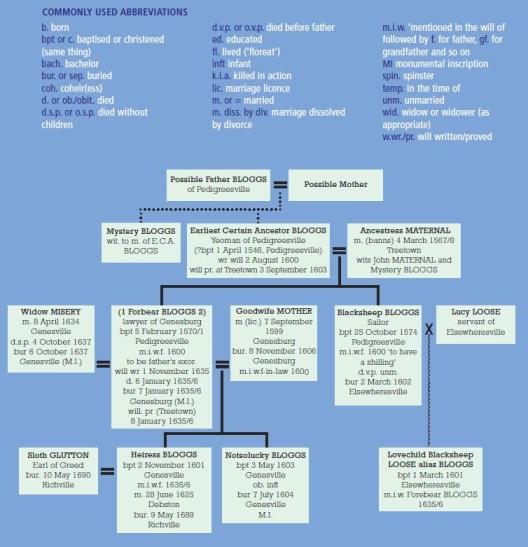

There are some sensible conventions and abbreviations, which you’ll need to know both for compiling your own charts and understanding other peoples’. These have been outlined above.

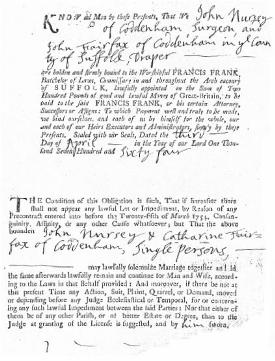

Marriage bond for John Nursey, surgeon of Coddenham, Suffolk.

EXPANDING ON THE BASICS

When it comes to writing up the family history, you can, again, decide what to say and how to say it, and you can get ideas from the examples in this book and the many published family histories and articles in family history journals and magazines.

It’s a good idea to try to relate the events in the family to the world around them:

This is a valuable exercise, which might actually help you find out more about them, or highlight inaccuracies or even mistakes in the family tree. It is also a good reminder that these were real, breathing people who existed in the world, not as pale shadows on old, dusty records. Indeed, if you think your ancestors only existed within the confines of parish register entries and, now, the forms generated by genealogical computer programs, it’s unlikely you will gain very much from family history, or that other people will enjoy and benefit from your hard work. The more you can think of and convey the idea of your ancestors as real human beings, the more fun – and success – you’re likely to have.

PRESENTING YOUR RESULTS

HERE IS THE SAME information about the Fairfax family, presented as a narrative pedigree, a prose account and a traditional family tree.

NARRATIVE PEDIGREE

John Fairfax, born about 1710, married Mary Hayward on 16 September 1735 at Framlingham, Suffolk. He was a draper and grocer of Coddenham and wrote his will in 1751, naming his executors as his wife Mary and brother-in-law John Hayward. It was proved 2 June 1758 (Suffolk Record Office IC/AA1/184/49). His children (details of which are recorded in the family bible) included:

1. Frances, born 24 May 1736, baptised 25 May and died 31 May, Stowmarket.

2. Mary, born 9 June 1738, baptised 26 June at Stowmarket.

3. John Fairfax, born 30 June 1739, died 15 weeks old, buried at Stowmarket.

4. John Fairfax, born 30 August 1741. Left a watch by his father. Married Penelope Wright at St James’s, Bury St Edmund’s, on 5 May 1770. Elected freeman of Bury St Edmunds, 1802. Death recorded in Gentleman’s Magazine as being in a fit on 12 February 1805 while visiting ‘a friend [sic], Mr P. Nursey, at Little Bealings’. He had two children: