Полная версия

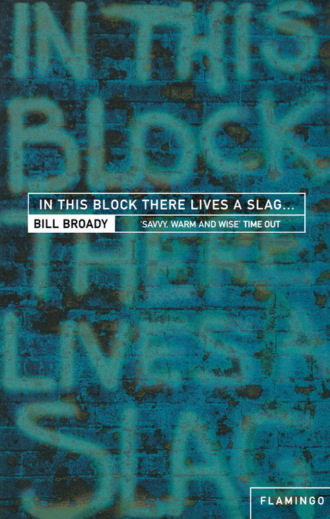

In This Block There Lives a Slag…: And Other Yorkshire Fables

In This Block There Lives a Slag…

And other Yorkshire fables

Bill Broady

To Jane Metcalfe

‘There are angels!

There are angels!

Dwelling within and without the city.

Guarding and watching.

Permitting and limiting

Powers, principalities and thrones’

– Sun Ra, ‘The Magic City’

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Epigraph

Wrestling Jacob

In This Block There Lives A Slag…

Songs that Won the War

My Hard Friend

Mr Personality in the Fields of Poses

Coddock

Tony Harrison

The Hands Reveal

The Kingfishers…The Distances

A Short Cut Through the Sun

Bouncing Back

The Tale of the Golden Bath-Taps

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Wrestling Jacob

‘…For we wrestle not against flesh and blood,’ St Paul wrote, ‘but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.’ I don’t know whether the Ephesians paid any attention to such exhortations but the only thing I ever wrestled with was Jacob.

I remember the pains and pleasures of our strivings…How the ground seemed to buck like a ship’s deck beneath my planted feet, while a pressure built in my chest as if a second, internal adversary was trying to force his way out through my sternum…How I tried to stifle my gasps for fear of having to acknowledge some repressed sexual imperative…How my head reeled from my opponent’s mephitic breath, with his flaring nostrils suggesting that he found mine equally repulsive…I remember the soft rustling and sudden stench as he chose, mid-combat, to void his bladder and bowels, and the dead clack of horn against bone, as if there was no mediation of flesh or fleece…

To wrestle spiritual wickedness, principalities and powers would, I imagine, seem a breeze after freestyle grappling with a Swaledale ram.

When I first met Jacob he was about nine months old – a wether hogg, running with the yard-dogs. A wall-eyed liver-and-white collie, a fulminating black hellhound and a grey-masked sheep: they looked so frightening that you knew they just had to be safe. He’d copy their leaps and bounds, trampolining on his front legs with an Elvis-style snarl, simulating a tail-wag by withershins rotation of his white stub and even managing a feeble bark – like my college tutor clearing his throat before demolishing my drug-addled thesis on ‘Beauty and The Sublime’.

His mother had died nameless in a snowdrift: his sister, Jessica, nannygoat-fostered, had long since slipped meekly back into the flock. It had been unusual to house-rear and bottle-feed a ram – ’But there was always something special about him,’ said the farmer’s wife, vigorously scratching Jacob – his eyes shuttering in ecstasy – behind the ears. ‘Do you believe in reincarnation?’ she asked. ‘He sometimes reminds me of my granddad.’ She struck me as unusually sentimental for a farmer’s wife. Her tabby cats had evidently taught Jacob to bury his own shit and to spittle his inner forelegs to wipe-wash his face. He could climb, too – regularly breaking his kennel chain and scrambling back through the pantry window. ‘He misses the telly,’ she told me, ‘But you can’t house-train a sheep. Mind you, we can’t even house-train the kids.’ With a pitted slab of toad-grey tongue Jacob licked her hand. ‘He’s unusually loving,’ she said, giving me a sharp, sideways look. ‘Especially for a male.’

On those late summer evenings I’d leave work sick with shame – as if this latest Exclusive Estate was something we’d half-demolished, rather than half-built – and I’d drive like the devil up the valley towards the fells. How I hated those silent, roofless houses, like emptied cereal packets, each supposedly ‘individuated by their unique window shapes and dispositions’ – insane shufflings of portholes, dormers and bays. I didn’t like to think of the lives people were going to have in them: I lived – unindividuated – in one myself. Exclusive, like Auschwitz: I was having those silly concentration camp dreams again. Only when I’d climbed to the heather line could I breathe properly: my mind stopped racing and I accepted that my dad was dead and Pam would never come back, that my novel was rubbish and that all my aches and ailments were psychosomatic and all my railings against the world mere self-pity.

Beyond the farm, up the beckside, along the crinkled ridges then, in the gloom, back down the steepest of the disused smelters’ tracks: I never tired of this habitual walk. The light, the wind, the shadows were always different: angles and distances seemed to change – landmarks shifted position so that one day I’d be unable to locate a familiar cup-marked rock but the next would go straight to it. The dogs soon stopped barking and ignored me but Jacob always greeted me with obvious delight. He’d launch himself, legs extending sideways to control and accelerate his progress down the shifting scree, like double sculls over water…then my hand would cup his chilly muzzle – he’d picked up purring from the cats but was able to simultaneously sound up to four discrete trills and rattles. I’d given up on even the possibility of affection from any source, so this enthusiasm meant a lot to me. I’d long suspected that while we only ever see in other people that which we desire or fear, animals can calmly scan and judge – from aura to essence – the whole of us.

That winter they moved Jacob to the big field, building him a stone-flagged log shelter, wired and tarpaulined to keep out the rain: I wondered if there was a television in there. He’d sit on his threshold, as if fronting the essentials of life, like Thoreau at Walden. His co-tenants – three doomed, embittered geese – periodically assaulted him: he’d just stand still, unblinking, lost in the transcendental, while they pecked themselves out, to finally collapse, exhausted and choking, their beaks wadded with fluff Sometimes he’d jump the wall and, unhefted, move about the hirsels, wrecking the grazing systems, even reaching the Herdwicks beyond the hause. Mandibles clicking like a power loom, he passed over the grass like a blight, leaving not so much as a green stain. No one seemed to mind, although the other sheep avoided him – more out of respect than aversion, slipping away if he dowsed towards them. The farmer and his wife bore oblations: Waldorf salad seemed to be Jacob’s staple diet. Where would it end? Suppose they were to anthropomorphize their entire stock?

Jacob would roll his eyes sarcastically if I joined the weekend procession of red and yellow hooded figures trudging into the mist but then follow to share my sandwiches and crop around me when I stopped to read. Sometimes the farmer joined us: once he told me that the only book he remembered reading was Papillon. He said it was wonderful but that he’d only got seventy pages in: what with the weather, the seasons, the animals and their births and deaths, his world must have seemed already fully-stocked with wonders. Jacob would always walk me back to the car park, often even trotting a few hundred yards down the lane in pursuit…In the driving mirror I’d see him gradually slow, stop, then turn away in apparent desolation.

The wrestling began one afternoon as we sat by the side of the summit tarn. I was lost in the epicene, exquisite world of Firbank’s Vainglory, absently patting Jacob whenever he nudged my arm. At last, with a hurt and derisory snort, he moved away. Then there was a pause – ‘just long enough,’ as Firbank puts it, ‘for an angel to pass, flying slowly.’ What happened next I had to piece together later: at the time it felt as if I’d been struck by lightning. He must have retreated for a considerable distance, like a fast bowler pacing out his run-up, then turned and charged into my back, tumbling me, legs still crossed, for what seemed a full half-dozen revolutions. As I struggled to my feet he was dancing around like a boxer, head jerking back with an evil, equine grin of triumph. I grabbed his horns like bicycle handlebars and twisted as if I was trying to unscrew his head. Then he reared up on his back legs and pushed – I pushed back. Then he pulled and I pulled and we fell on to all fours, then rose up again. And so we proceeded, in a stately to-and-fro waltz, to circle the water, until the ridiculousness, the sheer delight of it hit me and I collapsed, helpless with laughter. Jacob was trying to laugh too but a series of explosive sneezes was the best he could do. My copy of Vainglory had been trampled, well-pulped in the process: I wondered how aesthetic Ronald would have got on against Jacob – OK, probably, better than the Hemingways and Mailers.

The next morning my face and neck were scarlet-rashed from friction with that coarse fleece, more kemp than wool. In the following months my body was mapped with bruises, their colours shifting through the spectrum, as if I was turning into a chameleon. My shins were the worst: Jacob’s pipe cleaner legs kicked like steel-capped Docs. These welts didn’t hurt – they seemed, strangely, to have taken my previous pains away. Every Sunday morning we’d wrestle. Sometimes he’d stop fighting and suddenly become dead weight, sheer mass, toppling on to me like an oak wardrobe…At others he’d abruptly break my hold, as if my fingers had been cobwebs, then amble off, cropping…But usually I’d force him down and press one horn to the ground for a three-count. I was under no illusions, though: he was letting me win – he could have decked me any time he liked. Once, as we were locked in close combat, I lost my balance and rolled him over in an inadvertent Kamikaze Krash, stunning him. I saw something like respect in his glazed, refocusing eyes before he laid me low with a butt to the breadbasket. He’d imparted an extra twist to his horns that left my spleen twanging – for the next two days I was pissing blood. I realized that all these animals bred to slaughter for our covering and food could turn and crush us in an instant. The terrible goose-strikes absorbed by Jacob’s coat would have broken my arm or leg: a well-organized herd of Friesians could devastate a town – I liked to imagine them, rampaging through the Vista View Estate.

Whenever Jacob rushed towards me – like a fist-shaped, fast-blown cloud – I felt a residual flicker of fear. Suppose this was a different sheep, an evil cousin on a family visit? Or suppose he’d forgotten me? When I dive into water I always wonder if I’ll still be able to swim and when I get into my car I fear that I won’t remember how to drive – or, rather, I fear that the water or the machinery will have forgotten that I’m supposed to be – however notionally – in charge. I didn’t drown, I didn’t crash and Jacob kept letting me win. Sometimes the farmer and his wife would watch – he’d offer tips as an ex-Cumberland wrestler, she’d suggest that we do a novelty act at Grasmere Sports – or passing tourists took photographs, leaving lines of small denomination coins on top of the field gate; but mostly we fought unobserved, under the shadows of the domed, silent mountains, like decrepit titans who’d long ago fallen asleep or died.

Our wrestling reminded me of something I’d read or heard about – maybe archetypal, out of anima mundi? – but I could find no sources in the legends of Greece or Rome, The Golden Bough or Joseph Campbell. Maybe I was a new god, making my own mythology from scratch? There was only the British Museum’s beautiful sandstone relief of Khnum of Elephantine, the ram-headed god who created first the sun, then the pantheon of other divinities, then at last, out of Nilotic silt, formed Man on a potter’s wheel. Perhaps the dust in me was raging at its creator, all my constituent atoms striving to return to their previous carefree existence as motes? Or were they embracing him in thanks, celebrating by mock contention his gift of life? Khnum: Lord Of The Two Lands, Weaver Of Light, Governor Of The House Of Sweet Life, Guide And Director Of All Men – I tried these titles out on Jacob but he either didn’t or pretended not to recognize them.

Not only had I entered a second, blissful childhood – with a best friend who was always ready to play out – but the next three years were also my golden time of bewildering sexual success and potency. Although Jacob was gelded, maybe I’d picked up some residual pheromones in our rollings? Younger girls wanted to learn about life, while older women wanted help to forget what they already knew. To teach or divert, to reveal or conceal, to disturb or console? – luckily, these two contrary roles involved my saying and doing the same things, in roughly the same order. For that second, crucial assignation I’d always suggest a nice country stroll: taking them to meet Jacob was like a rite of passage. I’d put on my paint-stained jeans, well-holed sweater and ancient Barbour jacket, crusted with lanolin and suint, impacted with boluses of mud. One girl asked me if we were going potholing, another – sniffing – if I was a fan of Charles Bukowski.

They never seemed to wonder why I’d begin shouting when we got out of the car. Jacob, on hearing my voice, would run towards us. We could feel the earth shake, hear his hooves thudding like tymps: the air seemed to shimmer, and there was a malevolent hissing sound like expelling steam – I suspected that he’d been taking lessons from the stud bulls in the next valley. Eyes bugging, swollen to twice his normal size – awful personification of rapacious nature and patriarchal lust – he’d arrow towards his victim, the maiden sacrifice…but then, with a great wordless cry, I’d throw myself upon him and we’d grapple. Curiously, none of my companions ever screamed after his initial appearance, never ran for safety or assistance, never even tried to help me with so much as a prod of a dainty foot. They’d just drape themselves, Andromeda-style, over the badger-shaped boulder to watch the show. Maybe mine was a common ploy and they were thinking oh no, here comes that old tame sheep routine again? Whatever, they obviously soon realized that the monster was harmless…When I finally turned towards them – with the dragon slain, or at least pin-failed – I’d always see laughter transfiguring their features and glimpse for an instant, behind all their masks, the same woman’s face. No one I recognized…it certainly wasn’t Pam or Mum. Then she’d chuck the parchment-like folds under Jacob’s chin as he, nuzzling, gave out his full polyphonal hum. Then she’d kiss me – long and deep – and I’d tell her my secret lover’s name: nothing occult or sentimental, just what was on my birth certificate, but unshortened, undiminished.

Jacob’s particular favourite was Marianne: hair sun-bleached to white, I think he took her for some goddess or perhaps just another sheep. He let her ride him round the field: I wanted so much to, there and then, couple with her, like the incestuous Phrixus and Helle on the back of their magic golden ram…There was Jan the artist who put in her contact lenses to study him: she said that his fleece reminded her of some Manzoni achromes in the Herning Kunstmuseum. She clapped her hands with joy to see nature so sedulously imitating art: that night, the same transformative enthusiasm was able to perceive my scanty, rufous pubic hair as Titianesque…And there was Janine, who took the best photo of Jacob – just-sheared to designer stubble, in my homburg and shades: she said he looked like Bruce Willis and that she fancied him more than me…The only one who wouldn’t touch him was Helen, who walked the winter mountains bare-midriffed, with lacy halter-top, leopard-print stretch leggings and open-toed silver sandals: but who still beat me to the summit…Jane fed him mangetout peas, posing like Louise De Kerouaille – decollété, her raw nipples burning white-hot…Caro spent hours plaiting his wool into dreadlocks and epigonic hippie Sara decked him in fantastical garlands, like Bottom…‘It’s like in Genesis,’ said Bernie, lapsed Catholic and mild masochist. ‘If you’re wrestling with Jacob then you must be an angel.’ Which was the exact opposite of what she was calling me a mere seventeen days later.

Within a month they all lost their various illusions: no longer wanting to explore or hide, seek or find, make love or fuck – at least not with me – they went their separate ways. They tired of me at about the same moment that I tired of them, but the farewell messages left on my answerphone or scrawled in Alma-Tadema greetings cards were oddly bitter. In what way had I been using them? – I’d never once mentioned the future or, indeed, the past…Whenever I turned up alone Jacob didn’t want to wrestle. He’d shake his head, wobbling his overshot jaw: ‘I can get you women OK,’ that look said, ‘But you just can’t keep them’. I told him how I only wanted to keep that first smile, first kiss, first night…how I wanted someone I’d never get used to, that intimacy would render yet more and more unfathomable and who would, finally, make me a stranger – ever stranger – to myself. Jacob just sighed and returned to his cropping. He didn’t get it, but then in certain matters he was still very much a sheep.

That final winter was the best time of all. Everything thrilled me: I’d sleep three hours a night but arise full of energy. I had life taped: I felt as if, after thirty-four years, I’d at last got up the courage to be young. Being on the fells was like an acid trip: I was really seeing things – not just the sweeps of peak and scarp but also every insect, every tiny blade of grass and flower beneath my feet…all the details, but God, not The Devil, seemed to be in them. Everything kept going pointilliste, as if my gaze was penetrating through to that dust from which Khnum had created the world. I wondered if I’d somehow learnt this from Jacob: was it a mystical vision or just a sheep’s-eye view? I was worried about him: some days he wouldn’t come out at all – from the shadows of his cabin I could sense a baleful stare. Perhaps while I’d contracted his blitheness he’d been taking on my fears and guilts?

I no longer endured work but actively enjoyed it. The houses seemed to vanish into their components – a whirl of bricks and mortar, of glass, scaffolding and rances gleaming in the January sun. Vista View and the Parthenon were both ultimately just piles of stones. As Sally the macrobioticist told me: ‘Everything is edible if you chop it up small enough.’ My relationships were getting shorter and shorter, as if my lovers were also perfectly content with intensity and evanescence: although I was slightly perturbed when the two I liked best both sat down the instant they got home – after the first, unforgettable night – to write that they never wanted to see me again. Both ended with the same phrase: ‘I’m sorry I can’t share your feelings’. I didn’t understand what this meant: maybe there were husbands or other lovers in the picture? I hoped that I hadn’t somehow made them afraid of me.

One Sunday the traffic was heavier than usual. We crawled up the valley: Easter. A charity fun run was assembling. Every car was full of nuns and spacemen, ballerinas and demons. The sheep fled in panic from pantomime cows and horses. My companion was annoying me. She said her name was Miki – ‘Short for what?’ I asked – ’Short for nothing,’ she replied. Thirteen years younger than me – a third-year music student at York – she didn’t seem to realize that I was supposed to be telling her things. I’d never heard of her favourite writer – Broch – or her favourite composer – Barraqué. She talked about performing the latter’s setting of the former’s Death Of Virgil, in which, apparently, the dying Nolan, embittered, contemplates destroying ‘The Aeneid’. I suspected a trap: perhaps she’d made them both up so that I’d either feel ignorant or – if I did claim some distant familiarity – run the risk of revealing myself to be a fake? She started singing: ‘Il sera possible de traverser la porte corne de la terreur pour atteindre a l‘existence’…To enter being through the horned gates of terror: I thought of the waiting Jacob’s baroque crown and smiled…

As we passed the farm he still hadn’t appeared: I could only see, at the bottom of the field, a motionless human figure. It appeared to be contemplating, in the lee of the wall, a last remaining snowdrift. The summoning shout died in my throat: by the time its echoes had finished rolling round the cliffs I had almost reached him. The farmer, looking up, scissored his dangling arms across his thighs, like a cricket umpire signalling dead ball. He’d taken off his cap, holding it folded and crushed in his fist: his scarlet scalp was dappled with greenish patches of hair, like moss. Two long creases had appeared in his face, conduiting the tears past his pillar box mouth to drop off his chin and on to the still mound of Jacob, lying collapsed on his stomach. The legs seemed to have disappeared, as if the dust had already begun to consume the god that had moulded it. I knelt and touched him: he was stiff, immovably heavy – harder and colder than the Badger Stone, as if he’d never been alive. A chill wind had begun stripping his fleece like a dandelion clock. I looked up and met Miki’s eyes – uncomprehending, hard, young…as she watched two middle-aged men sobbing inexplicably over a pile of dirty wool. And I knew that now Jacob – metasheep, laughing wrestler, Lord Of The House Of Sweet Life – was gone, no one – not for a few days or hours, not even for a second – was ever going to love me again.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.