Полная версия

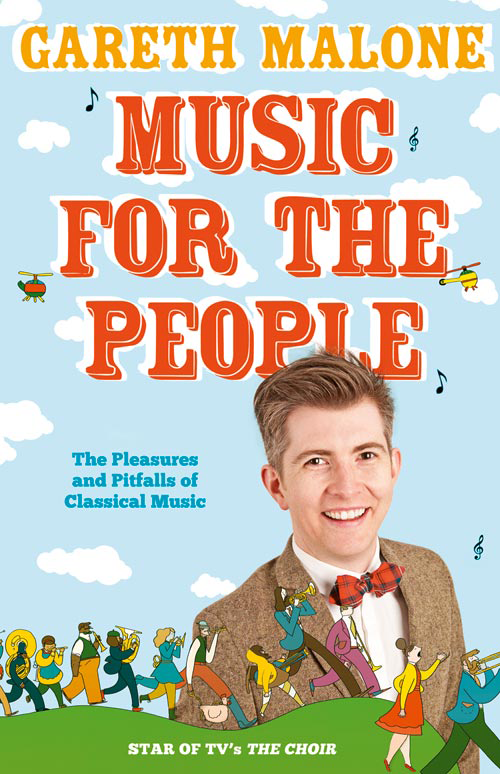

Gareth Malone’s Guide to Classical Music: The Perfect Introduction to Classical Music

Gareth Malone

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE

The Pleasures

and Pitfalls of

Classical Music

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

Part 1: LISTENING

1 You Love Classical Music – Yes, You Do!

2 Why, Why, Why?

3 How to Listen

4 A Hot Date with Music

5 Exploding the Canon

Part 2: DISCOVERING

6 The Secret of Melody

7 The Magic of Harmony

8 Style and the Orchestra

9 Grand Designs: The Structure of Music

Part 3: PERFORMING AND SURVIVING

10 The Singers not the Songs

11 Taking Up the Baton: Conductors

12 How to Survive a Concert

Coda

Part 4: APPENDICES

1 Musical ‘Starting Points’

2 Useful Information

3 Suggestions for Further Listening

4 Bibliography

5 Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dedication

For Becky and Esther

Epigraph

“There are a million things in music I know nothing about. I just want to narrow down that figure.”

ANDRÉ PREVIN (1972)

“Why does everyone else in the office think you’re from Mars if you ever go to the opera?”

MY MATE CHRIS (2010)

Introduction

I’ve always listened to classical music because my parents carefully indoctrinated me from birth. As a baby I would go to sleep to This is the Record of John by Orlando Gibbons (think men in ruffs singing in high voices). As a young child I felt that classical music was more interesting that popular music; I remember clearly, aged eight, being very disappointed when a girl told me that she only liked pop music. The relationship would never have worked. Over the intervening 27 years I’ve dabbled in all sorts, including pop, rock and acidjazzfunk. I’m always excited when I hear something that I haven’t heard before. Music knits together the tapestry of my life; it reflects my mood and it offers me nourishment. I love to read about it, to perform it but most especially to listen to it.

Next to my CD player I have a pile of music that I’m currently listening to: Stile Antico singing Tudor Christmas music; Muse’s The Resistance; and Verklärte Nacht by Schoenberg. In my office I have the music that I listen to less regularly: Nicolai Gedda singing opera arias; ‘Living Toys’ by Thomas Adès; and almost the complete works of Bach. In the loft is a huge box of music I don’t need to listen to again for a very long time (mostly from my teenage years): the KLF back catalogue, six versions of Progen by The Shamen and all my Janet Jackson records. I’ve always been obsessive and when I get my teeth into a piece it can be a year before I relegate it to the dustier sections of my CD rack.

If you are just coming to classical music for the first time, then it might seem as impenetrable as fine wine, learning Greek or taking up mountaineering. It’s true that there is a mountain of music to listen to and if I started listening now I’m sure it would take me the rest of my life to work my way through the back catalogue of recordings stocked in my local classical CD shop (HMV on Oxford Street, as regretfully the small independent stores are now few and far between, thanks to internet downloads). But it isn’t necessary to sample every piece to feel that you are getting a handle on this amazing music. When you know a couple of works well and understand how they fit into the general picture of music, you will quickly overcome your initial trepidation.

This book isn’t comprehensive – it’s a tour guide and a personal ramble through music based on my own interests and discoveries. The intention is to spark connections and points of departure for you. I will take you through the history of music later in the book, but this isn’t a lesson, it’s an impassioned plea to give this music a chance and a pocket guide (if you’ve got big pockets) to help you when you need assistance. Let us forage together.

Part 1 LISTENING

Chapter 1

You Love Classical Music – Yes, You Do!

Before we start let’s get a few things straight:

1 There is so much to know about music that a lifetime’s study couldn’t hope to tell you everything.

2 There are so many hidden alleyways, nooks and crannies in music that it’s quite possible to get stuck in just one area and neglect all the other music. There is much to challenge you, expand your horizons and generally give your musical taste a spring clean.

3 You are in control of what you listen to, where you start and where you finish. Only you know what you like and what you don’t like. It’s fine to admit that you simply don’t ‘get’ a piece – sometimes music takes time to get to know, or sometimes you’ll just never be friends.

4 There is no one correct way to listen to classical music or any other kind of music because it’s an intensely personal business.

Discovery

‘Discovery’ is the name given to the London Symphony Orchestra education and outreach department by its founder Richard McNicol, my mentor and music education guru. He chose this name because for him that’s the best way for people to connect with music: when they make the discovery themselves. This is your guide to discovering music.

Richard told me a story which illustrates the importance of feeling that music belongs to you. He encouraged a group of children to create music based loosely on ideas taken from a piece for full orchestra by the great Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. The children worked on these pieces for weeks before performing them to their schoolmates. At the end of the project the schoolchildren attended a concert of Stravinsky’s work. After the concert a young boy spoke to Richard and asked him ‘Here, mister, how did that Stravinsky know our music?’

I was lucky enough to work closely with Richard for two years at the LSO, watching how he brought people to music and not the other way round. An overly didactic approach often fails with music because I can’t make you like something. I can only point you in the direction of it and hope that you hear what I hear. I also hope that through using this book you will come to feel that music does indeed belong to everyone and that much of this wonderful repertoire can be yours. There’s no instant answer to understanding or knowing about classical music; the first step is building a positive relationship with the music.

Inexplicably, certain works have a hold on me and refuse to let go. I could listen to Bach’s Mass in B Minor every day without growing tired, whereas some pieces, although fascinating, don’t put down roots in the way that a truly great work does. What appeals to me might not appeal to you and although I do make recommendations in this book I’m aware that my evangelism for a piece may fall on stony ground. This book is not a prescriptive list of works that you should appreciate. The purpose is to give you the tools to make your own discoveries.

Most people struggle with pieces that are too complex or simply not tuneful enough for their taste. Length and complexity are factors in limiting appreciation of music but there is much to recommend on the musical nursery slopes before you tackle the great summits.

Music appreciation is as subjective as any other artistic discipline because our brains are changed by any musical experience we have during our lives and that in turn affects how we listen to new pieces. Although I make a case for the importance of a little background research in Chapter 4 there is no right way to listen to Mozart and there never will be. You should not feel that Mozart is somehow superhuman and therefore beyond your comprehension.

I have seen time and time again how anyone can learn to appreciate music. During my years working for English National Opera’s Baylis Programme (their community and education wing) I was sent to schools in deprived areas of London. From Hackney to the less salubrious parts of Ealing, if there was a school whose pupils knew nothing of opera then I’d be sent there, armed only with a score, an opera singer and a répétiteur (official term for an opera rehearsal pianist). What I observed was the dramatic effect these workshops had on students’ attitudes towards opera.

One of the most striking examples of the success of this practical approach to learning about music was working with some young homeless people at St Martin-in-the-Fields. We brought a singer from the ENO Chorus to sing ‘Vissi d’Arte’ (‘I lived for art’) from Verdi’s Tosca. For most people it’s rare to get so intimate with a voice that has been trained to fill every corner of an opera house. It’s like standing next to a jumbo jet on a runway (though it does sound a bit better). Huddled round in their slightly shabby canteen, drinking strong, sugary tea from polystyrene cups, these young people were profoundly affected by the physical presence of a large operatic voice: they couldn’t believe it. The voice didn’t belong in that space and it transported us all. We explored the story of Tosca – a bleak and violent opera – and I genuinely believe that their opinion of the art-form was transformed. They spoke with the singer, they heard from us about production at ENO and most importantly they took part by singing sections of the opera.

I’m not saying that they all became opera fans, but it was clear that until then they had completely the wrong impression of opera: ‘fat ladies screaming’. It’s interesting how many people can carry a vivid – and sometimes prejudiced – impression of what opera is like, having only experienced it from those adverts for ‘Go compare’ or ‘Just one Cornetto’. Within a few hours we started to recalibrate that popular misconception, using a little knowledge of the story, a basic understanding of how some of the music was composed and the unforgettable experience of hearing an opera singer in the flesh. Given this sort of preparation the most unlikely children can sit through up to three hours of opera, something many adults struggle with.

For me these workshops were a baptism of fire, because in order to prepare I would often be sent the music just a few days in advance and I’d have precious little time to get to know a new opera before being sent into a school as an evangelical advocate. The discipline of sitting with a score (the written musical notes), reading the synopsis (the plot), digging out the programme (if I could find one), reading the director’s production notes (if they’d written any) and living with the music for a few days before being hurled into a school was an excellent cramming course. The job gave me the opportunity to talk to singers from the production, to grapple with the themes during workshops – and finally after all that I’d go to see the opera for the first time. If they’d known then how little I knew about opera, and how much study I was having to do, perhaps they’d have employed someone else. It proved an excellent training for opera appreciation.

So sometimes, in order to appreciate music, a little homework is required. My dad’s school motto was ‘nil sine labore’ – ‘Nothing without work’ (how I loathed it when he stood over my piano practice quoting this aphorism). I’m afraid it applies here, but it needn’t be a chore. Of course I understand that by some definitions music that requires ‘work’ is an anathema – surely we should love a great piece of music at first listening? But think how often you meet someone and fall in love at first sight – once in a lifetime? Many pieces of music take time to get to know.

I’m assuming if you’ve bought this book about classical music then you are ready to apply yourself. So let’s move on.

You know more than you think you do

Whether you notice it or not, classical music is everywhere, keeping teenagers at bay in train stations,1 persuading you to buy wine on TV adverts and pulling no punches in film soundtracks. I believe it is the ultimate destination for all true music lovers. Once the sheen has rubbed off lesser forms, the gems of classical music shine even brighter.

If you’re reading this book, then it probably means that you already feel that you know a little something about classical music. Maybe you’d like to know more. Or perhaps, like Socrates, you know enough to know that you don’t know anything. Hopefully you have been enticed to dip into this strange and wonderful world. This book is intended to build on your tentative enthusiasms; I’m here to help. If, as I hope, you have enjoyed any classical music, there will be something in this book for you. Once you discover an area of music that you like, given the number of composers and over 500 years of Western musical history, there are hundreds of discoveries to be made.

Don’t panic

You’ll never get to know every piece of music because there’s just too much out there and you may not like everything you hear, but that doesn’t mean you don’t like classical music. There are pieces of music I haven’t got my head round – either they are too sickly sweet or too bitter, too angular and modern or not modern enough. I think it’s important not to feel that if you don’t like a piece you should give up on it straight away. Having said that, I gave up on Bruckner a few years ago after a spectacularly tiresome concert experience, but who knows, perhaps I’ll grow back into it. And it’s important not to feel overwhelmed by how much music there is to listen to.

The chief difficulty in learning about any art-form is the ‘emperor’s new clothes’ effect. We’ve all been there – a friend eulogises about a piece of music. ‘You’ve got to hear this! It’s amazing! Listen to that cymbal crash!’ Their face is terrifyingly alive. Their hair is standing on end. They are in the throes of what can only be described as a personal moment. Meanwhile, you are wondering what all the fuss is about. Everybody experiences music differently. Several factors can affect this: the context, how much you know about the piece and how often you have heard it before.

Try listening to a piece of classical music that you know well in a variety of contexts: (1) while washing up; (2) while looking at cherished photographs; (3) while keeping an eye on the sports result as your favourite team loses/wins. You’ll find that the atmosphere of the piece changes and affects the activity as much as the activity affects the music.

Technical language

In this book I will tell you what I consider helpful in understanding how melody, harmony and the structure of music work but without turning this into an A-Level textbook. Terms such as staccato and legato may be alien to you but the concepts they signify will be familiar (they mean ‘short/detached’ and ‘smooth’, respectively). Getting to grips with how music works is a technical business and unwrapping a technical term reveals yet more layers of technical terms underneath, like an endless game of pass the parcel. Technical terms can be daunting but I make no apologies for taking you through the first few layers and teaching the basics that you need to enhance your understanding. You need them because they stand for concepts for which there is no other word: harmony, melody, sonata, symphony, concerto, etc. But wherever possible I will explain any terms, avoid overly technical language and use everyday alternatives where they exist.

There are many books available which attempt to explain everything there is to know about how music functions but which for the beginner are utterly bewildering in their depth and density of language: it’s not necessary to be a mechanic to drive a car. Music is at once incredibly simple – a child can appreciate and perform it – and also complex – philosophers, scientists and musicians are still perplexed by many of the mysteries of music; for example, why exactly are we moved by certain pieces and not others? Why exactly do some people love Bach while others cannot abide him? Despite years of study and masses of knowledge, these are still matters for debate. Some technical aspects of music can be left unexplained without impairing your appreciation.

Over-familiarity breeds contempt

These days I wouldn’t choose to go to a concert of Ravel’s Boléro despite it having a terrific melody and for many years being one of my favourites. I first heard it when it was about seven years old when Torvill and Dean were at the Olympics: I thought it was very stirring. It was then used on television programmes for the next ten years, almost on a loop; when I got to secondary school we studied it for GSCE; when I started to work at the LSO it was part of an education concert to show the different sections of the orchestra. It’s a pretty simple piece: the melody repeats itself around the entire band before building to a grand finale for full orchestra. Ravel issued a warning about the piece before its first performance: ‘a piece lasting seventeen minutes and consisting wholly of orchestral tissue without music … There are no contrasts, and there is practically no invention except in the plan and the manner of execution.’2 I still feel that it’s a great piece of music, but I just can’t listen to it any more because not only is the Boléro itself repetitive but I’ve also heard it repeated everywhere from lifts to restaurants.

If pressed, most experts will acknowledge that such familiar pieces are in many ways wondrous compositions; it’s just that they wouldn’t pay money to hear them again because over-familiarity has set in and hardened minds. I am guilty of this attitude because I’ve been listening to classical music for most of my life, and I think that regardless of the musical genre people take a similar position towards music they think of as less complicated or lower-brow. It’s a matter of perspective: after listening to heavy rock music, pop-rock might seem rather tame; likewise if you’ve just been listening to a Mahler symphony, which may have a profoundly intense and emotional effect on you, then a waltz by Johann Strauss may feel light and frivolous and less than satisfying.

Making a discovery of a piece of music is a very personal business. The first time you hear a melody and it connects with you can be highly significant; I can recall the first hearing of all my favourite music with startling immediacy. It’s extremely discouraging to discover that a piece you have fallen in love with is not considered ‘great’. For example my friend Aaron when he was about twenty had one piece of ‘serious’ (i.e. classical) music in his collection: Má Vlast by Smetana. It’s a glorious piece of music whose second movement describes the River Vltava from its early springs to the confluence of the river as it flows towards Prague. The structure is simple but effective, the melody (based on a folksong) is appealing and the orchestration is stirring, plus it was a piece he liked.

We sat in our university halls and listened to it, and I found it incredibly moving, not having heard the piece for many years (my primary school music teacher Mr Naylor played it to me in 1986). However, Aaron was humiliated when speaking to a music student of ‘serious classical music’ about Smetana, who somewhat sniffily said they ‘considered Má Vlast to be rather lowbrow’. I can imagine the avant-garde music that this music student was being exposed to in music college and I suppose that Aaron’s Smetana CD must have seemed naïve by comparison.

Don’t let this put you off. If you like a piece then that’s just fine. Perhaps by the time you have listened to The 100 Greatest Classical Hits in the Universe … Ever a few times you’ll be screaming for something different. Until that time, just enjoy.

Film scores

If you watch films then you probably know more classical music than you think you do. Many directors edit their films to existing works. The most famous example of this was Stanley Kubrick, who was a musical magpie. 2001: A Space Odyssey, Eyes Wide Shut, The Shining, Barry Lyndon and A Clockwork Orange, among others, contain classical music used to piercing effect. Nevertheless many composers have created original works for the cinema and great composers of the twentieth century took up the challenge of composing for film.

However, composing for film is a very different business. Film composers are not in charge of their own work; the director is the boss. In 1948 the Englishman Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote the score for Scott of the Antarctic. In a salutary lesson to all students of film composition, he wrote the music before seeing the film. The result was that much of the music never made it on to the screen because the film that the director had made did not require all of the music that Vaughan Williams had written. But no matter, because Vaughan Williams used it to create his Seventh Symphony, Sinfonia Antarctica.

Despite music playing second fiddle (pun intended) to the drama, some scores have become well known in their own right, and are written by composers who have made careers out of writing for film and neglecting concert music. The scores for Psycho and Cape Fear by Bernard Hermann, Batman by Danny Elfman, The Great Escape by Elmer Bernstein, Jerry Goldsmith’s stridently modern Planet of the Apes and the many scores of John Williams can compete with music written for the concert platform. Many ‘straight’ or ‘legit’ composers have also been drawn to the world of film, especially in its early days. The 1938 score for Alexander Nevsky by the Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev is a great example of a piece that transcends the constrictions of the genre. In the 1990s the film score was performed in a concert version with the film projected behind the orchestra. This sort of meeting of the film world and the orchestral world is a mark of their mutual respect, although a more cynical view would be that orchestral musicians like film work because it pays well and film directors like orchestras because they elevate banal stories.

Because of the technical demands of film composition it has now become a separate discipline requiring pinpoint timing and an understanding of how music and image combine to create cinema. Too much scoring can overpower a scene; not enough and the scene can lack meaning. For a film score to earn the respect of classical musicians it must stand up to the same scrutiny as concert music which does not have the benefit of a moving image and must hold the audience’s attention on purely musical grounds. But there are examples of pieces that have stood out from the film and had me whistling for weeks after leaving the cinema.