Полная версия

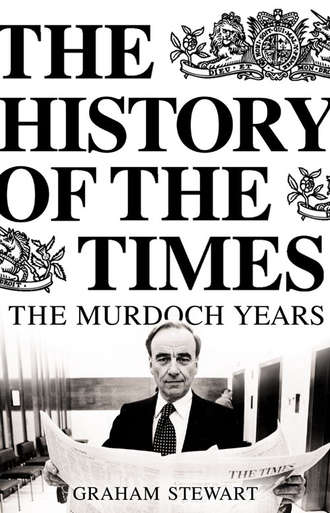

The History of the Times: The Murdoch Years

In fact, Murdoch had already scented blood. Back in September, he had bumped into Lord Thomson in the Concorde departure lounge at JFK and gained from him, however obliquely, the impression that TNL would not remain within the Thomson empire for much longer. Murdoch, indeed, had greater forewarning that The Times would be up for sale than had its editor. But whether the owner of predominately tabloid titles, a man who gave little impression of wanting to join the British Establishment, could be persuaded to take the bait and rescue The Times still remained far from clear.

Whichever projection was favoured, The Times was not on any rapid course to profitability. Although it had edged into the black during the early 1950s and for one tantalizing moment in 1977, it had been losing money for the vast majority of the twentieth century. A paper with such a track record would have been shut down long ago had it not been for its reputation and the manner in which being the proprietor of The Times conveyed a position in public life that had a value of its own. Gavin Astor, who became (alongside his father) proprietor in 1964, described the newspaper as ‘a peculiar property in that service to what it believes are the best interests of the nation is placed before the personal and financial gains of its Proprietors’.[25] But a proprietor’s belief in his role as a national custodian was not necessarily appreciated by less sentimentally minded shareholders. When Roy Thomson bought The Times in 1966 he recognized that it would not be a cash cow and, in order not to trouble shareholders’ consciences with it, opted to fund it out of his own exceptionally deep pocket. In 1974 this decision was reversed when the Thomson Organisation’s portfolio diversified further into other interests, including North Sea oil, whose profitability dwarfed TNL’s losses. The only commercial argument for retaining The Times was that as a globally recognized quality brand, it (at least psychologically) added value as the glittering flagship of the Thomson Line. Unfortunately, in becoming a byword for unseaworthiness, it risked very publicly bringing down Thomson’s reputation for business savvy and managerial skill. From that moment on, it became a matter of floating it out into the ocean and abandoning ship.

When it came to the announcement of sale, the Thomson board maintained that although they had failed, a new management team might be able to turn the paper around. This was a predictable statement – The Times could not easily be sold by asserting it had no viable future whoever owned it. But no serious forecaster believed it could be turned around quickly. Could supposedly ‘short-termist’ shareholders be expected to understand a new owner’s perseverance? In this respect Murdoch offered more hope than some potential bidders because he and his family owned a controlling share of his company, News International Limited. Thus, so long as Murdoch saw a future for the paper, News International could carry The Times through a long period of disappointing revenue without its survival in the company being frequently challenged by angry shareholders. And given the profitability of the other stallions in the stable, the Sun and the News of the World, there was every reason to expect that the banks would continue to regard News International as creditworthy.

On the other hand, appearing to have an excess of available money also threatened The Times. Journalists and print workers who regarded their paper as a rich man’s toy could be expected to want to joy ride with it. This had been part of the problem with the Thomson ownership of TNL. Roy Thomson was the son of a Toronto barber who described purchasing The Times when he was aged seventy-two as ‘the summit of a lifetime’s work’. An Anglophile, he renounced his Canadian citizenship in order to accept a British peerage (as the future Canadian proprietor of the Daily Telegraph, Conrad Black, would later do). He took as his title Lord Thomson of Fleet – the closest a peerage could decorously go towards being named after a busy street. Not only did he describe owning The Times as ‘the greatest privilege of my life’ he announced that in acquiring it, the paper’s ‘special position in the world will now be safeguarded for all time’.[26] This was a hostage to fortune. Owning STV (Scottish Television) had provided much of the financial base for his British acquisitions and he had once famously described owning a British commercial television station as ‘like having your own licence to print money’. He appeared to accept that owning The Times was a licence to lose it.

II

Fleet Street, whose pundits were paid daily to indict others for failing to put the world to rights, was noticeably incompetent in managing its own backyard. For those proprietors already ensconced, there was at least the compensation that this created a cartel-like environment. The huge costs of producing national newspapers caused by print unions’ ability to retain superfluous jobs and resist cost-saving innovation acted to ward off all but the most determined and rich competitors from cracking into the market. Competition from foreign newspapers was, for obvious reasons, all but nonexistent. The attempts through the Newspaper Publishers’ Association to act collectively against union demands were frequently half-hearted. No sooner had the respective managements returned to their papers’ headquarters than new and deadline-threatening disputes would lead them to cobble together individual peace deals that cut across the whole strategy of collective resistance. During the 1970s, it was widely understood that one of the major newspaper groups had resorted to paying sweeteners to specific union officials who might otherwise disrupt the evening print run.

By 1980, Fleet Street’s newspapers were the only manufacturing industry left in the heart of London. The print workers came predominantly from the East End, passing on their jobs from father to son (never to daughter) with a degree of reverence for the hereditary principle rarely seen outside Burke’s Peerage or a Newmarket stud farm. They were members of one of two types of union. The craft unions, of which the National Graphical Association (NGA) was to the fore, operated the museum-worthy Linotype machines that produced the type in hot metal and set the paper. The non-craft unions, in particular NATSOPA (later amalgamated into SOGAT), did what were considered the less skilful parts of the operation and included clerical workers, cleaners and other ancillary staff. Almost any suggested change to the working practice or the evening shift would result in a complicated negotiation procedure in which management was not only at loggerheads with union officials but the officials were equally anxious to maintain or enhance whatever differential existed with their rival union prior to any change. The balance of power was summed up in a revealing and justly famous exchange. Once Roy Thomson, visiting the Sunday Times, got into a lift at Gray’s Inn Road and introduced himself to a sun-tanned employee standing next to him. ‘Hello, I’m Roy Thomson, I own this paper,’ the proprietor good-naturedly announced. The Sunday Times NATSOPA machine room official replied, ‘I’m Reg Brady and I run this paper.’[27] In 1978, the company’s management discovered that this was true.

The print unions operating at Times Newspapers, as at other Fleet Street titles, were subdivided into chapels, individual bargaining units intent on maintaining their restrictive advantage. The union shop steward at the head of each chapel was known as the father. He, rather than anyone in middle management, had far more direct involvement in print workers’ daily routines. The father was effectively their commanding officer in the field. The military metaphor was a pertinent one for, although the position of father was an ancient one, the Second World War had certainly helped to adapt a new generation to its requirements. Non-commissioned officers who, on returning to civvy street, were not taken into management positions often found the parallel chain of command in the chapel system to their liking.

At Times Newspapers there were fifty-four chapels in existence, almost any one of which was capable of calling a halt to the evening’s print run. TNL management’s attempt to enforce a system in which a disruption by one chapel would cause the loss of pay to all others consequently left idle had been quashed. And chapels often had equally scant regard for the diktats of their national union officials. When in 1976 the unions’ national executives got together with Fleet Street’s senior management to thrash out a ‘Programme for Action’ in which a change in work practices would be accepted so long as there were no compulsory redundancies, the chapels – accepting the latter but not the former – scuppered the deal.[28]

It was not only those paying the bills who despaired of this state of affairs. Many journalists, by no means right wing by political inclination, became resentful. Skilled Linotype operators earned salaries far in excess of some of the most seasoned and respected journalists upstairs. As Tim Austin, who worked at The Times continuously between 1968 and 2003 put it, ‘We couldn’t stand the print unions. They’d been screwing the paper for years. You didn’t know if the paper was going to come out at night. You would work on it for ten hours and then they would pull the plug and you had wasted ten hours of your life.’ The composing room was certainly not a forum of enlightened values. When Cathy James once popped her head round to check that a detail had been rendered correctly she was flatly told where a woman could go.[29]

Relations had not always been this bad. The Times had been printed for 170 years before it was silenced by industrial action, the month-long dispute of March to April 1955 ensuring a break in the paper’s production (and thereby missing Churchill’s resignation as Prime Minister) that even a direct hit on its offices from the Luftwaffe during the Blitz had failed to achieve. But the 1965 strike had affected all Fleet Street’s national titles. Times print workers had not enjoyed a reputation for militancy until the summer of 1975 when the paper’s historic Blackfriars site in Printing House Square was put up for sale and the paper, printers and journalists alike transferred to Gray’s Inn Road as the next-door neighbours of Thomson’s other major title, the Sunday Times. The decision to move had been taken as a cost-cutting measure – although the savings proved to be largely illusory. The consequence of bringing Times print workers into the orbit of those producing the Sunday Times was far more easily discernable. Even in the context of Fleet Street, Sunday Times printers had a reputation for truculence. Partly this was attributed to the fact that they were largely casuals who worked for other newspapers (or had different jobs like taxi driving) during the week and were not burdened by any sense of loyalty to the Sunday Times. Industrial muscle was flexed not merely through strike action but by a myriad minor acts designed to demonstrate whose hand was on the stop button. Paper jams occurred with a regularity that management found suspicious. Such jams could take forty minutes to sort out and result in the newspaper missing the trains upon which its provincial circulation depended. But from the print workers point of view, paper jams meant extra overtime pay. Newsagents began referring to the newspaper as the Sunday Some Times.[30]

More important than industrial action or sabotage was the effect the print union chapels had on blocking innovation. Muirhead Data Communications had developed a system of transmitting pages by facsimile for the Guardian back in 1953 but, because of union hostility, no national newspaper had dared use the technique until the Financial Times gritted its teeth and pressed ahead in 1979.[31] By then, The Times – in common with all other national newspapers – was still being set on Linotype machines (a technology that dated from 1889). Molten metal was dripped into the Linotype machine, a hefty piece of equipment that resembled a Heath Robinson contraption. As it passed through, the operator seated by it typed the text on an attached keyboard. Out the other end appeared a ‘slug’ of metal text which, once it had cooled, was fitted into a grid. It would then be copy checked for mistakes. If errors were spotted, a new ‘slug’ would be typed. Once the copy was finally approved, it would proceed to ‘the stone’. There, it would be encased in a metal frame. This was the page layout stage, from which it was ready to be taken to the printing machines. It was an antiquated and occasionally dangerous (the hot metal could spatter the operator) method of producing a newspaper, not least because most of the rest of the world – including the Third World – had long since abandoned Linotype machines for computers. Thomson had purchased the computer equipment but had to store it unused in Gray’s Inn Road pending union agreement to operate it. Using computer word processors to create the newspaper text for setting out was a far less skilled task than operating the old linotype machines. In 1980, journalists were still using typewriters. Their typed pages were then taken to the Linotype operator who would retype in hot metal. But with computerized input, journalists could type their own stories directly into the system, negating the need for NGA members to retype anything. This was part of the problem – it would make redundant most of the Linotype operators and, if followed up by other Fleet Street newspapers, would soon threaten the very existence of a skilled craft union like the NGA. Thus the union officials at TNL refused to allow the journalists to type into a computerized system unless their own union members typed the final version of it. In other words, if journalists and advertising staff typed up their text on their own computer screens, NGA members would have to type it up all over again on computer screens for their exclusive use. This was known as ‘double-key stroking’ and negated any real saving in introducing computer technology.

Management’s attempt to break the NGA’s monopoly on keying in text in favour of journalists having the powers of direct input was one of the causes of the shutdown of The Times for just short of a year between November 1978 and November 1979. Led into battle by TNL’s chief executive, Marmaduke Hussey, management attempted to force the print unions to conclude new deals that would pave the way for the computer technology’s introduction. When no comprehensive deal emerged, management shut down the papers in the hope of bringing the unions back to the negotiating table. As a strategy it proved a miserable failure. It cost Thomson £1 million a week to keep its printing machines idle and to have a nonexistent revenue from sales or advertising. The fear that The Times’s best journalists would be poached by rival newspapers ensured that all the journalists were kept on on full pay to do nothing. This was a clear signal to the print unions that there was no intention to shut down The Times permanently. Furthermore, they could also see that, buckling under the costs, the management were increasingly desperate to resume publication. By sitting it out, the printers could drive a harder bargain.

Management did attempt one daring breakout. It was often alleged that it would be cheaper to print the newspaper abroad and airfreight it into Britain than print it under the restrictive practices of Fleet Street. What was certainly the case was that 36 per cent of advertising revenue in The Times came from overseas. So it was decided to print a Europe-only edition that would at least show that the paper was alive and could feasibly be produced elsewhere. A newspaper plant in Frankfurt agreed to undertake the task. This proved most illuminating. In Fleet Street, NGA compositors doing ‘piece work’ managed to type around 3500 characters an hour. They defended their high salaries by pointing to this level of expertise. But the German compositors in Frankfurt – women (all but barred by the Fleet Street compositors) working in a language that was not their own – managed 12,500 characters an hour (in their own language they could set 18,500).[32] Such statistics told their own story.

But if a point was proved by the exercise, it was the value of brute force. The British print unions persuaded their German brothers to picket the plant. With ugly scenes outside, the German police discussed tactics with Rees-Mogg who was at the Frankfurt site for the launch. They offered to use water cannon on the crowd in order to clear a path for the lorries to transport the first edition out of the plant but they could not guarantee subsequent nights if the situation deteriorated further. Meanwhile, inside the plant, various sabotage attempts were being detected, including petrol-soaked blankets that had been placed near the compressor – potentially capable of causing a massive explosion, which, as Hussey put it ‘might have blown the whole plant and everyone in it sky high’.[33] Reluctantly, Rees-Mogg gave the order to abandon production. Once again, management’s attempts to circumvent their unions had been humiliatingly defeated.

In November 1979, the TNL management formally climbed down and called off the shutdown. They had failed to secure direct input for journalists or to get the print workers to agree legally binding guarantees of continuous production. The only upside to this humiliation was that management was prevented from installing what would actually have been the wrong typesetting system (a disastrous discovery Hussey made late in the dispute when he visited the offices of The Economist and realized his mistake).[34] The shutdown meant that The Times, which had long claimed to be Britain’s journal of record, had reported nothing for almost a year. Among the events it was unable to comment upon was Margaret Thatcher’s coming to power. The total cost to Thomson exceeded £40 million. The unions’ concession was that – already obsolete – computer typesetting would be introduced in stages but that NGA operatives would ‘double-key stroke’ all text.

That The Times returned at all after a stoppage of such duration was impressive. That it returned with circulation figures similar to those it had enjoyed before the shutdown was an extraordinary testament to the quality of the product and the extent to which its readers had mourned its absence. Indeed, such was the economics to which Fleet Street was reduced that the eleven-month shutdown left little enduring advantage to The Times’s competitors. The Times’s absence had increased their market opportunity. The Daily Telegraph, in particular, made gains. But gains involved pushing up production levels and this was only achieved at a cost that met the increase in sales revenue. When The Times returned, its rivals had to scale production down again but, thanks to union muscle, they were unable to cut back the escalating cost that had been forced upon them in the meantime.[35]

It might have been imagined that the journalists’ frustration at the print workers would have bonded them more closely with management in ensuring that The Times saw off its tormentors, but the failed shutdown strategy made many of them equally critical of TNL executives.[36] Indeed, the success of the print workers in defending their corner emboldened some of the more militant Times journalists to see what would happen if they too pushed at a door that was not only ajar but loudly banging back and forth in the wind.

During the 1970s, salaries for Times journalists had lagged behind the spiralling inflationary settlements of the period. But during the shutdown, Thomson had kept faith with its Gray’s Inn Road journalists by continuing to pay their full salaries during the eleven months they were not actually doing anything. Furthermore, they were given a 45 per cent pay increase in 1979 to make up for previous shortfalls.[37] Despite this, in August 1980 the journalists went on strike when TNL offered a further 18 per cent pay increase instead of the expected 21 per cent.

Of the 329 members of the paper’s editorial staff, about 280 were members of the National Union of Journalists (NUJ). The union meeting at which the decision to strike was made took place when many were away and – although it represented a majority of those who turned up to the meeting – only eighty-three actually voted for industrial action. They were responding to the call of The Times NUJ’s father of the chapel, Jake Ecclestone, who argued that it was a matter of principle: an independent arbitrator had suggested 21 per cent and in offering only 18 per cent TNL had refused to be bound by independent arbitration. That the NUJ chapel had also refused to be bound by it was glossed over.[38]

While the independent arbitrator had concentrated upon what he thought was the rate for the job, TNL had to deal with a law of the market: what they could reasonably afford. The difference between the two pay offers amounted to £350 a journalist but, if the knock-on effect of subsequent negotiations with the print workers was factored in, then TNL maintained the difference was £1.2 million. There was certainly collusion between print and journalist union officials in calling the strike. Although many journalists crossed the picket line, the NUJ had taken the precaution of getting the NGA to agree to go on strike too if management attempted to get the paper out.

Management had long come to accept that dealing with those who printed the paper was a war of attrition against a tenacious and well-organized opponent. But the attitude now displayed by some who actually wrote the paper was too much to endure in silence. The strike ended after a week but it destroyed the will of the existing management to persevere. When The Times returned on 30 August, its famous letters page was dominated by readers of long standing who had loyally waited for their paper’s return during the eleven-month shutdown but who now felt utterly betrayed. ‘It is impossible to believe in the sense, judgment or integrity of your journalists any longer’ was one typically bitter accusation. Subscriptions were cancelled, sometimes in sadness but frequently in anger at the fact that ‘you and your staff can have no feeling for your advertisers and readers. Other newspapers do not get into these situations. Your ineptitude beggars belief.’[39] But the most important lecture came not from disgusted of Tunbridge Wells but in the day’s leader column, written by Rees-Mogg himself. ‘How to Kill a Newspaper’ ran the length of the page. It washed the paper’s dirty linen in public and some staff disliked the idea that their editor was writing a leader chastising the actions of many of his own colleagues. Jake Ecclestone, ‘gifted but difficult’, was even named in the sermon that laid out before readers exactly the scale of journalists’ pay increases over the previous two years and contrasted it with the extent of the newspaper’s losses. Rees-Mogg pulled no punches, claiming that there could be no such thing as dual loyalty, for a journalist ‘is either a Times man first or an NUJ man first … if the strikers do not give their priority in loyalty to The Times … why should they expect that the readers, or indeed the proprietor, of The Times should continue to be loyal to the paper?’[40]

This was very much to the point, for the Thomson board had been meeting to debate that very question. Although it was denied at the time, it was the NUJ strike that tipped the balance in convincing Thomson executives to dispose of The Times and, with it, the other TNL titles.[41] Sir Gordon Brunton had called senior colleagues to his beautiful country house near Godalming, Surrey, and it was there that the decision was taken. This was then ratified by the Thomson British Holdings board and, over the telephone, confirmed with Lord Thomson of Fleet. Preferring to live most of his time in Canada, Ken Thomson had taken over the family empire on the death of Roy, his father, in 1976. He felt little of his Anglophile father’s obvious pride in owning The Times. In the end, the ultimate proprietor did not take much persuading although, naturally, in the press release he stated, ‘it grieves me greatly’.[42] It was Harold Evans, editor of the Sunday Times, who put it succinctly: ‘One can’t blame Lord Thomson … the poor sucker has been pouring millions into the company and has been signing agreements which have been torn up in his face.’[43] Roy Thomson’s dream of securing The Times’s future forever had ended after only fourteen years and at a cost of £70 million. The Spectator’s media pundit, the historian Paul Johnson, summed up the situation: