Полная версия

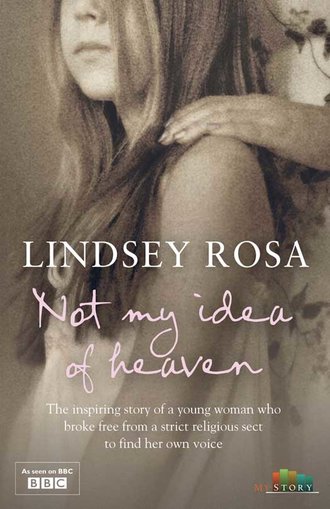

Not My Idea of Heaven

‘Hi, Lindsey,’ Gareth said.

I had never seen a boy with his trousers undone, and I revelled in my good fortune. The real ambition of a Fellowship girl was to get married and have loads of Fellowship children, and Gareth was the boy I’d already decided I’d marry when I was grown up. Now I could be certain.

That night when I said my prayers I thanked God for letting me see Gareth’s willy. He certainly worked in mysterious ways.

Chapter Four

The Carpenter, the Dreamer, the Romantic and Me

When I was little, I shared a room with my sisters, Alice and Samantha. Our beds were lined up side by side, mine being the small one in the middle. There was just enough room to squeeze between them, but I didn’t mind that it was cramped: I felt safe, flanked by my two big sisters. No bogeymen would come and get me in the night.

Our room had a very posh-looking set of fitted wardrobes covering one wall, but in the middle there was a recess to accommodate a little dressing table and its mirror. It was there that Alice sat to prepare herself for bed every night, but Samantha and I were rarely awake to see her. Being older, she attended the evening meetings, and Samantha and I had usually fallen asleep by the time she returned home.

One evening I awoke and saw her, lit by the little pull-string light above the dressing table, peering intently at herself in the mirror. I spied on her from beneath my blankets, hoping she wouldn’t notice me. She was talking to herself gently, slowly plaiting her long hair. I watched her carefully secure two plaits with hair bands. Then came the part I remember most clearly. She opened the dressing table drawer and took out several curlers. These were not the old-fashioned tubes, but plastic clasps, covered in foam. Taking the tassel of hair that hung below her hair bands, she wrapped it around the curlers and fastened them. I shivered with excitement. How daring my big sister was! We were not supposed to try to make ourselves look pretty in any way. I wondered how she managed to sleep with those hard lumps on her pillow, but I guessed it must be worth it.

Alice really wanted to look her best because she was madly in love. She had met the man of her dreams – another Fellowship member. They had eyed each other during meetings, and, despite the seating plan, a Fellowship courtship had ensued. As far as anyone knew, Alice and Mike had never kissed or as much as held hands, but they did speak on the telephone. They spent hours talking each evening.

Young adults in the Fellowship typically met future spouses during a special three-day meeting that could take place in any country where Fellowship disciples were found. The Fellowship made no secret of the purpose of these events, which were a unique opportunity to widen the gene pool. Fellowship women were required to follow their husbands, which meant that as a woman you could end up living almost anywhere in the world. In Alice’s case, she struck it lucky: her beau lived just around the corner!

Alice was so busy with her love affair that she failed to notice that everyone else her age was doing their GCE O-Levels and ended up leaving school with barely any qualifications. As it happens, this wasn’t much of a problem.

Fellowship women were not expected to have careers, just a short stint working in a local office, as Alice did, and then on with the business of marriage. Their job was to reproduce and look after the household. The men were encouraged to gain skills as apprentices at Fellowship firms. University was out of the question, as it was seen as a place where subversive ideas circulated.

The biggest ambition we were expected to have was to get into Heaven. That was the dream.

If Alice was the romantic, Samantha was the dreamer. Actually, she was a romantic too. I can’t say how she got on at school, being six years younger than she was, but academia was never her strong point. Still, if there was a qualification for fantasizing about romance and other lives, she’d probably score even better than I would.

I can only assume that Samantha’s teachers gave her a hard time for doing badly in class, because that is what she gave me when we played teachers and pupils in one of our favourite games. Well, it didn’t remain one of my favourites for very long, but she certainly liked it. It always seemed to revolve around her telling me off, saying I hadn’t done my maths properly. Samantha’s persona took the form of an extremely strict teacher who frequently made me cry. I was an easy target, of course – I hadn’t even started school yet!

When we played shops, we’d take tins out of Mum’s kitchen cupboards, and tubes of toothpaste from the bathroom, balancing all of our stock on top of a wicker linen basket. It lived on the landing at the top of the stairs, where it was ideally placed for receiving reluctant customers on their way to the toilet. On top of the basket we’d place a plastic till, which we were both desperate to operate. Whoever got to the shower cap first could transform themselves into the shopkeeper by pulling it over their head. This shop uniform made us feel very professional!

Samantha and I didn’t play together for as many years as I’d have liked, simply because she was six years older than I, and soon tired of my childish antics. But what really brought the whole thing to a premature end was something I did to her, which I still feel bad about even now. I stole her only worldly friend away from her. Natalie had been a lifeline for Samantha, connecting her to the world outside of the Fellowship. For many of us, those links kept us sane. I think it broke her heart, and I don’t think she ever forgave me for that.

From then on, I felt as if I were the only child in the house. While she became more reserved, I busied myself with my worldly friends. My brother and sisters were growing up fast, but I still had a lot of playing to do.

There’s a lot I don’t know about my brother, Victor. He’d spent twelve years finding his feet in the male-dominated world of the Fellowship even before I was born. He was two years old when the Fellowship split into opposing subgroups, Mum and Dad ending up in the more extreme of the two, and my mum’s parents totally cut off from us in the other. Victor lived through all that, growing up in the 1970s. I know it all affected him greatly, but it didn’t stop him loving and treating me like his baby. And those twelve years that separated us might as well have been twelve minutes for all the difference they made to our relationship.

I really loved my big brother. I followed him everywhere and couldn’t wait for him to wake up in the morning. I listened out for his call for me as soon as his alarm went off and delighted in acting as his slave. On request, I brought him cups of coffee and ferried messages back and forth between him and Mum. She was much too busy to bother about my brother when he was lazing in bed, but that was OK by me.

I loved it when Victor helped me with projects. One time I designed a set of heart-shaped shelves, which he assisted me in making. Whatever I wanted, he’d find a way of incorporating it into his own woodwork projects during his apprenticeship as a carpenter. As was usual practice in the Fellowship, he left school at sixteen, skipping his A-levels and learning a practical trade.

Victor was really handy with a can of paint, and sometimes Dad entrusted him with it to touch up the rusty spots on his Fiat Panorama. Dad didn’t believe in spending money on new cars until he had run his current one into the ground. By the time he had finished with it, the bodywork would be more Polyfilla than metal. The Panorama was an estate car, which carted the six of us around, four in the front and two in the luggage compartment, hanging on for dear life. I was rather glad when the law for wearing seat belts in the backs of cars was enforced a few years later.

Victor may have been handy with a spray can, but he couldn’t really be trusted with one. It always started off all right, then, having finished the job in hand, he looked round for more things to spray. On this particular occasion it was my tricycle that he turned to. I loved that little trike and whizzed around at top speed on it, leaning around the corners with one wheel off the ground. One day I dashed into the garage to grab it and, on seeing it, burst into floods of tears. Across the front of this dear little red trike was a spray mark of blue paint. It wasn’t a big mark, about the size of my four-year-old palm, but to me the blemish was the end of the world. I had no doubt in my mind who was responsible for this horrible stain.

‘Victor,’ I howled, ‘look what you’ve done!’

He popped his head out of the shed, a sheepish look on his face. ‘Sorry, Lindsey,’ he grinned. My anguish drained away at the sight of him, and immediately I forgave him. But I could never ride that tricycle again with quite the same pride. I got used to Victor’s destructiveness, though. I had to. He didn’t think twice about cutting my doll’s hair, and once even found he had crushed some of my toy cars in the vice that lived in the shed. He claimed they had been in a car crash.

When I was about nine, I asked Victor to take me out. What I really wanted was for him to take me fishing with him. He regarded me with a funny look on his face and said he wasn’t sure. I realized then that he was embarrassed by me. I wore clothes that didn’t fit in with the other girls my age and he clearly minded this detail. I was hurt by his embarrassment, and never asked him again. As I grew older, our relationship changed, and for a time we grew apart, but eventually events would bring us closer together again.

Chapter Five

Motherly Love

In one very particular way, I was a normal child. I was inquisitive, and wanted to know ‘why?’ all the time. Unfortunately, most of my questions, which I put to my mum and dad, were met with the same unsatisfying response: ‘Let the Lord into your heart and have faith,’ they would say. In other words, don’t ask questions. They might as well have been saying, ‘Don’t be Lindsey.’

One day I was in the kitchen helping Mum bake, when a question popped into my head.

‘How is God going to win the war against the Devil if there are more worldly people than Fellowship people?’ I mumbled through a mouthful of cake mixture.

‘Trust the Lord, Lindsey, He knows what He’s doing. And it’s very naughty to question Him.’

With no further questions, I carried on licking the spoon.

I wasn’t allowed to do sponsored charity events at school, so another time I asked, ‘Mum, how come we don’t give to money to charities that help people?’

‘That’s not what God has chosen us to do,’ Mum simply said. ‘There are other people to look after the poor.’

Being told that God had all the answers and there was no point trying to work anything out for myself was supposed to stop me asking questions. The problem was that it just gave me a great idea. If God had all the answers, I could ask Him. ‘Dear God, what am I getting for my birthday this year?’ I whispered, so Mum couldn’t hear me. She was standing at the foot of the beds making sure we said our prayers properly.

‘In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, Amen.’ I waited for my answer.

As far as Mum was concerned, all my questions about the ways of the world were unimportant. The Bible dealt with those completely and that was all there was to it. As I think she probably saw it, my questioning was just a minor diversion from the really important things in life. These were practical everyday things, such as baking and knitting. In a way, she was right. We had a great time together. Mum loved to buy Family Circle, a magazine for mums, full of arts-and-crafts ideas. She’d keep the best ideas in a folder and, when she’d finished all her jobs, we’d get out the paints, glue, glitter and scissors and get to work.

Mum also kept huge bags containing scraps of material and wool, which we used to make a collage man on one occasion. She drew the outline on a huge piece of paper and I stuck on wool for hair, buttons for eyes and various patches of cloth to make the clothes. She taught me to knit and sew, and we made clothes for my dolls.

When we weren’t doing arts and crafts we were either playing board games or heading out to the shops. It might not sound exciting, but I really enjoyed shopping with Mum, especially if we passed the post office with the cakes in the window. (It’s amazing how hungry you feel after posting a letter.) Bizarrely, it had a sweet counter at one end and a bakery at the other. I wasn’t so interested in the sweets, but Mum and I would make sure that we never went home without my cream bun and her horseshoe-shaped macaroon.

Two shops down from cake heaven was the hardware shop. Mum did a lot of practical jobs around the house, so we would often pop in there for one or two items on the way to the post office. One day, while she scoured the shelves for the things on her list, I waited at the front of the shop, watching as the man behind the counter measured out nails and hooks and weighed them on his scales. I was fascinated by the huge cast-iron weighing scales, which put Mum’s home set to shame. It was then that I noticed that the television fixed on the wall was on. I had seen televisions before but I had never had the chance to see one that was switched on. I looked up curiously.

There were some strange creatures dancing around in front of a row of houses. Popping out of the dustbin next to the steps was a shaggy-looking thing that was clearly neither a human nor an animal. I had no idea what I was seeing. I’d never seen anything like it before, but even so I was far more interested in getting off home with Mum and eating cake. That, not TV, was what was missing from my life at that moment in time.

I had some really nice times with Mum.

If Mum had to go to the doctor’s, or anywhere that involved a lot of waiting around, my grandma would take care of me for a few hours. Gladys was my dad’s mum, and she and my grandpa lived just a couple of minutes away by car. They rented a large Victorian terraced house from Uncle Hubert, who was married to my dad’s sister, Meryl. We’d always have to park in the multi-storey car park built directly behind the terrace, from where we could see Grandma if she was near her kitchen window. If she was looking out, I’d wave, and she’d be waiting at the front door by the time we got there.

I’d head straight out to the shed, which took up most of the tiny back garden and was used as a sewing room. I would sit at the old Singer sewing machine that stood just inside the doorway, thumping my foot on the treadle. I liked to pretend I was making clothes the way I saw Mum and Alice do.

Sometimes I’d see the stray cats that Grandma encouraged to come into her garden by leaving bowls of milk and scraps of food for them. I thought this was pretty daring, because Fellowship members were not allowed to keep pets, just in case they came to love them more than God. Maybe that rule was created just for Grandma, because she certainly loved them. Whenever we exchanged letters, hers would always tell me about the latest cats visiting her garden, and in my letters back to her I’d try to please her by drawing pictures of the ones she described.

I’d always hand my letters directly to Grandma when I saw her at the meetings. After the meeting was over, and everyone had gone outside, I’d run along the rows of benches to where Grandma was usually sitting, waiting for me. I’d tug her long plait of white hair and she’d creak round with a big smile on her face. I was always excited to have another letter for her. I’d ask when I could visit her, hoping to get my foot pumping on that treadle again. If my cousins, Hubert’s boys, were doing something at the house, she’d say, ‘Not this week, Lindsey, I’ve got the boys in.’ She loved her boys, possibly almost as much as she loved her cats.

The same can’t be said for Grandpa, who hated cats. Maybe he was afraid she’d love them more than him. Such was his dislike of them that there was a family legend involving him, a cat and a kitchen door. We all knew the story, but the truth of it was never confirmed. Apparently, he once caught a trespassing cat inside the house, and furiously slammed the door on it as it tried to escape. It was a horrible image and I didn’t want to think of Grandpa doing that.

One of the rooms upstairs in Grandma’s house was Grandpa’s office. He was always up there doing something, so if I was visiting I’d hardly get to see him at all. I’d often go up to a back bedroom to get a book for Grandma to read to me, and would pop my head round the door as I passed Grandpa’s office. He always seemed to be sitting at his desk with his back to the door. He wasn’t one for showing much affection, but if I went in he’d always stop what he was doing and invite me to choose a coloured sticker from the top drawer of his desk. In retrospect, I think they must have been items of office stationery, but I thought they were there just for me.

I particularly liked to be allowed to stay for lunch. Grand-ma’s special was crinkle-cut oven chips with dollops of ketchup. We just had the straight kind of chips at home, so I thought the fancy-shaped ones were wonderful. When it was time for lunch it was my job to run and sound the gong that hung from the ceiling in the hallway. This was Grandpa’s cue to put his stickers away and come downstairs.

After lunch I’d go upstairs to Grandma’s room to have a sleep on her big bouncy bed. It was covered with a large green eiderdown, which was so slippery that I had a job just getting on the bed in the first place. She’d lie down together with me and we’d cuddle up. At some point in the afternoon, Mum would arrive to pick me up. Mum never hung around to chat to Grandma, and I suspect they may not have got on too well, but to me she was special.

Chapter Six

The Ministry

Every month a package would arrive, delivered by a member of the Fellowship. This contained the books that told my parents how to live their lives. These were the Ministry, and we had accumulated hundreds of them. Victor’s carpentry skills were called into action by Dad, who got him to build several enormous sets of shelves and attach them to the walls on either side of the chimney breast in our dining room. They were completely filled with the volumes of the Ministry. Red books, green books, brown books, white books … I loved looking at the colours, but I wasn’t interested in what was in them. Mum and Dad would read every word, process the information and then tell me how a Fellowship girl was expected to behave.

Sometimes I went with Dad, and a few other Fellowship men, to the High Street to do some preaching. Everyone would stand with their back to the glass front of the local Woolworth’s store, while the men took it in turn to step forward to preach. No one ever came out of Woolworth’s to tell us to ‘piss off ’, so we must have had some sort of pitch licence.

When it was Dad’s turn, he would step forward into the bustling crowd with confidence and begin to read from the Bible earnestly. The thing I loved about Dad was that he seemed completely unbothered by the crowd. His confidence gave me confidence to be there; he made it seem like something to be proud of.

Most people just ignored us, but Dad carried on as if he had a captive audience. This happened once a month on a Saturday, when the high street was busy and there were no meetings to go, and it was the only time the Fellowship spoke publicly. I’m not sure if we were supposed to be converting sinners, but, if we were, it was a dismal failure. The only attention I remember getting was from the driver of a speeding white van, who slowed down just enough to shout out a volley of blasphemous abuse at us, before whizzing off in fits of laughter. Well, at least he showed some interest.

Reading all those ministry books and endless chapters from the Bible got tedious, even for Dad, so the reading of the daily broadsheet was a real treat for him in the evenings. Before starting he made sure he had everything he’d need to sustain him throughout the evening. First, he’d carefully snip the corner off a packet of peanuts and lean it against the leg of his favourite chair where he sat, so that they were within arm’s reach. This allowed him to slide his hand down and grab the packet without taking his eyes from the page. Nearby, he’d place a glass of sherry, which could also be located without looking.

Very carefully he aligned the pages of the paper, making sure he had the large cumbersome sheets under strict control. When everything was in order, he’d settle back in the armchair and balance the newspaper on his knees. Between regular munches of peanuts and sips of sherry, he gave sharp twitches of his head and nods of approval. If he got really involved in an article, he’d let out sharp lisping noises: the sound of him muttering under his breath. Victor and I found Dad’s habits hilariously funny. Without a TV, watching Dad was our evening’s entertainment.

Sometimes, he’d let out roars of laughter, calling out, ‘Edith, have you seen this?’ to which Mum would retort sharply, while her knitting needles clattered away, ‘Of course not, Peter, I’ve been far too busy.’

Eventually, Dad’s head would slump onto his chest and he’d begin snoring. This was our chance! Very carefully, one of us would begin to slide the paper from between his fingers. As soon as he felt the precious Telegraph slipping from his grasp, his head would snap up, and he’d shout, ‘I was reading that!’ and our chance was gone. And, of course, there wasn’t a hope in hell of taking away from Dad what was his only window on the world beyond the Fellowship.

Chapter Seven

School of Thought

When I was five I started my first year at the local primary school. At long last I was a big girl. I was particularly proud to be at the very same school my dad had attended when he was a lad. What’s more, I was following in the footsteps of Alice, Victor and Samantha. I couldn’t wait to let everyone in my class know that I had a big sister in the junior school. And I felt so important, putting on my best dress and shoes.

Samantha relished her big sister role, telling me which teachers to watch out for and what I could expect to encounter.

‘You’re lucky you won’t have Mrs Cook,’ she told me, enigmatically.

I wasn’t sure why this was meant to be lucky, but I nodded gravely. I accepted that Mrs Cook was capable of terrible things.

‘Your teacher,’ Samantha revealed, ‘is called Mrs Roland.’ Samantha had heard good things about Mrs Roland. Nothing terrible, anyway.

‘I’m going to call her Roland Rat,’ I announced. I had a sticker of Roland Rat attached to the headboard of my bed, so he meant a lot to me.

‘No, Lindsey, you don’t want to do that,’ she warned.

‘Yes, I do,’ I said defiantly, but I wisely never said it to Mrs Roland’s face.

Pretty soon, though, on the first morning, I was sitting in that Welfare office on the plastic chair, with all the Asian children. No one in the family prepared me for that.

The only preparation for school I was given by my parents was intended to make sure I followed the Fellowship rules while there. How I coped with that in the school environment was left up to me.

It was when I started school that I began to realize how my life really differed from those of the rest of my friends. I didn’t want to stand out, but having to follow the Fellow-ship’s rules made it difficult not to.

One of the first friends I made at primary school was Catherine. I can’t remember much about her now, but I must have thought she was nice, because I invited her back to my house. For some reason I decided that the Fellowship rule of not having worldly people in the house wouldn’t apply on that day. I was living in the moment and it seemed right. I was only five.

Mum was busy helping Alice make her wedding dress that day and had asked Catherine’s mum if she could walk me to the corner of Albion Avenue on the way home, to make sure I arrived safely. But when it came to saying goodbye I found myself asking, ‘Can Catherine come to my house and play?’