Полная версия

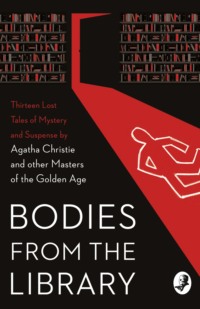

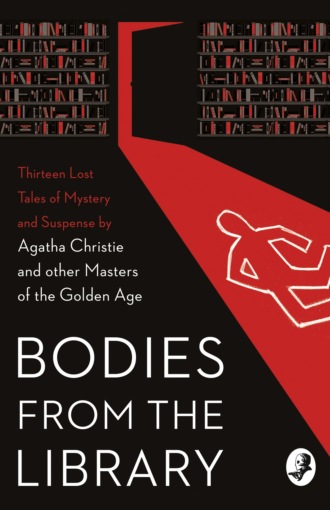

Bodies from the Library: Lost Tales of Mystery and Suspense by Agatha Christie and other Masters of the Golden Age

‘This seems explicit enough. “I leave all that I have to Nurse Sydney Eastcote, residing at Dr Prevost’s medical Institute.” I recognise the handwriting as Robin’s, and the date is in the same writing. Who are the witnesses, by the way?’

‘Two of the waiters at the hotel, I believe,’ Nurse Eastcote explained.

Wendover turned to the flimsy foreign envelope and examined the address.

‘Addressed by himself to you at the institute, I see. And the postmark is 21st September. That’s quite good confirmatory evidence, if anything of the sort were needed.’

He passed the two papers to Sir Clinton. The Chief Constable seemed to find the light insufficient where he was sitting, for he rose and walked over to a window to examine the documents. This brought him slightly behind Nurse Eastcote. Wendover noted idly that Sir Clinton stood sideways to the light while he inspected the papers in his hand.

‘Now just one point,’ Wendover continued. ‘I’d like to know something about Robin’s mental condition towards the end. Did he read to pass the time, newspapers and things like that?’

Nurse Eastcote shook her head.

‘No, he read nothing. He was too exhausted, poor boy. I used to sit by him and try to interest him in talk. But if you have any doubt about his mind at that time—I mean whether he was fit to make a will—I’m sure Dr Prevost will give a certificate that he was in full possession of his faculties and knew what he was doing.’

Sir Clinton came forward with the papers in his hand.

‘These are very important documents,’ he pointed out, addressing the nurse. ‘It’s not safe for you to be carrying them about in your bag as you’ve been doing. Leave them with us. Mr Wendover will give you a receipt and take good care of them. And to make sure there’s no mistake, I think you’d better write our name in the corner of each of them so as to identify them. Mr Harringay will agree with me that we mustn’t leave any loophole for doubt in a case like this.’

The lawyer nodded. He was a taciturn man by nature, and his pride had been slightly ruffled by the way in which he had been ignored in the conference. Nurse Eastcote, with Wendover’s fountain pen, wrote her signature on a free space of each paper. Wendover offered his guests tea before they departed, but he turned the talk into general channels and avoided any further reference to business topics.

When the lawyer and the girl had left the house, Wendover turned to Sir Clinton.

‘It seems straight enough to me,’ he said, ‘but I could see from the look you gave me behind her back when you were at the window that you aren’t satisfied. What’s wrong?’

‘If you want my opinion,’ the Chief Constable answered, ‘it’s a fake from start to finish. Certainly you can’t risk handing over a penny on that evidence. If you want it proved up to the hilt, I can do it for you, but it’ll cost something for inquiries and expert assistance. That ought to come out of the estate, and it’ll be cheaper than an action at law. Besides,’ he added with a smile, ‘I don’t suppose you want to put that girl in gaol. She’s probably only a tool in the hands of a cleverer person.’

Wendover was staggered by the Chief Constable’s tone of certainty. The girl, of course, had made no pretence that she was in love with Robin Ashby; but her story had been told as though she herself believed it.

‘Make your inquiries, certainly,’ he consented. ‘Still, on the face of it the thing sounds likely enough.’

‘I’ll give you definite proof in a fortnight or so. Better make a further appointment with that girl in, say, three weeks. But don’t drag the lawyer into it this time. It may savour too much of compounding a felony for his taste. I’ll need these papers.’

‘Here’s the concrete evidence,’ said the Chief Constable, three weeks later. ‘I may as well show it to you before she arrives, and you can amuse yourself with turning it over in the meanwhile.’

He produced the will, the envelope, and two photographs from his pocket-book as he spoke and laid them on the table, opening out the will as he put it down.

‘Now first of all, notice that the will and envelope are of very thin paper, the foreign correspondence stuff. Second, observe that the envelope is of the exact size to hold that sheet of paper if it’s folded in four—I mean folded in half and then doubled over. The sheet’s about quarto size, ten inches by eight. Now look here. There’s an extra fold in the paper. It’s been folded in four and then it’s been folded across once more. That struck me as soon as I had it in my hand. Why the extra fold, since it would fit into the envelope without that?’

Wendover inspected the sheet carefully and looked rather perplexed.

‘You’re quite right,’ he said, ‘but you can’t upset a will on the strength of a fold in it. She may have doubled it up herself, after she got it.’

‘Not when it was in the envelope that fitted it,’ Sir Clinton pointed out. ‘There’s no corresponding doubling of the envelope. However, let’s go on. Here’s a photograph of the envelope, taken with the light falling sideways. You see the postal erasing stamp has made an impression?’

‘Yes, I can read it, and the date’s 21st September right enough.’ He paused for a moment and then added in surprise, ‘But where’s the postage stamp? It hasn’t come out in the photo.’

‘No, because that’s a photo of the impression on the back half of the envelope. The stamp came down hard and not only cancelled the stamp but impressed the second side of the envelope as well. The impression comes out quite clearly when it’s illuminated from the side. That’s worth thinking over. And, finally, here’s another print. It was made before the envelope was slit to get at the stamp impression. All we did was to put the envelope into a printing-frame with a bit of photographic printing paper behind it and expose it to light for a while. Now you’ll notice that the gummed portions of the envelope show up in white, like a sort of St Andrew’s Cross. But if you look carefully, you’ll see a couple of darker patches on the part of the white strip which corresponds to the flap of the envelope that one sticks down. Just think out what they imply, Squire. There are the facts for you, and it’s not too difficult to put an interpretation on them if you think for a minute or two. And I’ll add just one further bit of information. The two waiters who acted as witnesses to that will were given tickets for South America, and a certain sum of money each to keep them from feeling homesick … But here’s your visitor.’

Rather to Wendover’s surprise, Sir Clinton took the lead in the conversation as soon as the girl arrived.

‘Before we turn to business, Miss Eastcote,’ he said, ‘I’d like to tell you a little anecdote. It may be of use to you. May I?’

Nurse Eastcote nodded politely and Wendover, looking her over, noticed a ring on her engagement finger which he had not seen on her last visit.

‘This is a case which came to my knowledge lately,’ Sir Clinton went on, ‘and it resembles your own so closely that I’m sure it will suggest something. A young man of twenty, in an almost dying state, was induced to enter a nursing home by the doctor in charge. If he lived to come of age, he could make a will and leave a very large fortune to anyone he choose: but it was the merest gamble whether he would live to come of age.’

Nurse Eastcote’s figure stiffened and her eyes widened at this beginning, but she merely nodded as though asking Sir Clinton to continue.

‘The boy fell in love with one of the nurses, who happened to be under the influence of the doctor,’ Sir Clinton went on. ‘If he lived to make a will, there was little doubt that he would leave the fortune to the nurse. A considerable temptation for any girl, I think you’ll agree.

‘The boy’s birthday was very near, only a few days off; but it looked as though he would not live to see it. He was very far gone. He had no interest in the newspapers and he had long lapses of unconsciousness, so that he had no idea of what the actual date was. It was easy enough to tell him, on a given day, that he had come of age, though actually two days were still to run. Misled by the doctor, he imagined that he could make a valid will, being now twenty-one; and he wrote with his own hand a short document leaving everything to the nurse.’

Miss Eastcote cleared her throat with an effort.

‘Yes?’ she said.

‘This fraudulent will,’ Sir Clinton continued, ‘was witnessed by two waiters of the hotel to which the boy had been removed; and soon after, these waiters were packed off abroad and provided with some cash in addition to their fares. Then it occurred to the doctor that an extra bit of confirmatory evidence might be supplied. The boy had put the will into an envelope which he had addressed to the nurse. While the gum was still wet, the doctor opened the flap and took out the “will”, which he then folded smaller in order to get the paper into an ordinary business-size envelope. He then addressed this to the nurse and posted the will to her in it. The original large envelope, addressed by the boy, he retained. But in pulling it open, the doctor had slightly torn the inner side of the flap where the gum lies; and that little defect shows up when one exposes the envelope over a sheet of photographic paper. Here’s an example of what I mean.’

He passed over to Nurse Eastcote the print which he had shown Wendover and drew her attention to the spots on the St Andrew’s Cross.

‘As it chanced, the boy died next morning, a day before he came of age. The doctor concealed the death for a day, which was easy enough in the circumstances. Then, on the afternoon of the crucial date—did I mention that it was September 21st?—he closed the empty envelope, stamped it, and put it into the post, thus securing a postmark of the proper date. Unfortunately for this plan, the defacement stamp of the post office came down hard enough to impress its image on both the sheets of the thin paper envelope, so that by opening up the envelope and photographing it by a sideways illumination the embossing of the stamp showed up—like this.’

He handed the girl the second photograph.

‘Now if the “will” had been in that envelope, the “will” itself would have borne that stamp. But it did not; and that proves that the “will” was not in the envelope when it passed through the post. A clever woman like yourself, Miss Eastcote, will see the point at once.’

‘And what happened after that?’ asked the girl huskily.

‘It’s difficult to tell you,’ Sir Clinton pursued. ‘If it had come before me officially—I’m Chief Constable of the county, you know—I should probably have had to prosecute that unfortunate nurse for attempted fraud; and I’ve not the slightest doubt that we’d have proved the case up to the hilt. It would have meant a year or two in gaol, I expect.

‘I forgot to mention that the nurse was secretly engaged to the doctor all this while. And, by the way, that’s a very pretty ring you’re wearing, Miss Eastcote. That, of course, accounted for the way in which the doctor managed to get her to play her part in the little scheme. I think, if I were you, Miss Eastcote, I’d go back to France as soon as possible and tell Dr Prevost that … well, it hasn’t come off.’

J. J. CONNINGTON

Alfred Walter Stewart, alias J. J. Connington, was born in Glasgow in 1880. A clever child with an enquiring mind, he attended Glasgow High School and graduated in 1902 from Glasgow University with honours in chemistry, mathematics and geology. While Stewart could have pursued almost any of the sciences he decided to focus on chemistry. After completing his doctorate in 1907, he took up an appointment at Belfast University where in 1919, after spells working for the Admiralty and lecturing at the universities of London and Glasgow, he became Professor of Chemistry, occupying this chair until his retirement in 1944. He had been suffering for many years from a debilitating illness, and he died in 1947.

Stewart had begun writing novels in the 1920s, adopting the pseudonym J. J. Connington doubtless to distance what he saw as a hobby from his academic career. His first book, Nordenholt’s Millions (1923), dealt with a Wellesian apocalypse, brought about by scientific error and ended—in the Clyde valley—by scientific genius. His second, Almighty Gold (1924), was a more prosaic tale of adventure and crime in the world of high finance. Both books sold well, and were well received critically, but this was the 1920s and what John Dickson Carr would later describe as ‘the lure of detective fiction’ was too great. For his first detective story, Death at Swaythling Court (1926), Stewart wrote an entertaining village mystery in which a blackmailing butterfly collector is poisoned and stabbed. This was quickly followed by The Dangerfield Talisman (1926), an ‘old dark house’ mystery with many characters and almost as many clues.

For Murder in the Maze (1927), Stewart created his first recurring character, Sir Clinton Driffield, an atypically misanthropic policeman who would appear in seventeen novel-length mysteries. Driffield is generally aided, and sometimes hindered, by his Watsonian friend Squire Wendover, a local landowner in the county where Driffield is the chief constable. Driffield is a far more active chief constable than is customary in fiction—or in real life—and, while he can tend to be didactic, he is one of only a handful of detectives in the Golden Age willing to admit, occasionally, that he is unable to explain every aspect of a case. And Driffield can also proceed in unorthodox ways, never more so than in the extraordinary Nemesis at Raynham Parva (1929).

As might be expected from a scientist, Stewart’s mysteries are careful and methodically written and, while some contemporary critics felt the author could sometimes be long-winded, the majority found him adept at constructing ingenious plots, entertaining and imaginative, and above all scrupulous at playing fair with the reader. His novels often feature memorable elements, such as the sinister legend of the Green Devil in Death at Swaythling Court, the hedge maze of Murder in the Maze, the lottery tontine of The Sweepstake Murders (1931) or the ‘fairy houses’ and weaponry museum in Tragedy at Ravensthorpe (1927).

‘Before Insulin’, the only short story to feature Driffield and Wendover, was first published in the London Evening Standard on 1 September 1936 as the final story in Detective Cavalcade, a series of stories selected by Dorothy L. Sayers.

THE INVERNESS CAPE

Leo Bruce

‘You’d think I was used to violence, wouldn’t you?’ asked Sergeant Beef, rhetorically, after all the crime and horror I’ve seen. But there was one crime of violence, I remember, which shocked me more than any of your sneaking poisoners could do. It happened some years ago now. One old lady was clubbed to death in full view of her crippled sister. The most brutal case I ever had to tackle.

I knew the old ladies well; nice kind old parties who would do anyone a good turn. They lived together in a big house overlooking their own park. The only thing that anyone could have against them was that they were rich.

Miss Lucia was the older of the two and must have been over seventy. She was active, though: moved like a young woman and loved her garden, which was kept ‘just so’ by two gardeners and a lad. Miss Agatha was a few years younger and no one had ever seen her out of her invalid chair since the bad hunting accident she had as a young girl. She would be wheeled out on to the terrace on fine days and sit there watching her sister in the garden. They were very fond of one another and very happy.

Then their nephew came to live with them, young Richard Luckery, and I didn’t much take to him. It was known that he hadn’t any money of his own and he must have had a lot from the old ladies because he spent like a madman. Motor-cars, racing, racketing about—an extravagant young devil who cared only for himself.

Perhaps what I didn’t like was that he used to dress in the most extraordinary clothes; eccentric, that’s what he looked. And when he started wearing one of those Inverness capes and a deerstalker hat, like Sherlock Holmes, I thought it downright silly.

He had friends to play up to him, though, like anyone else who throws money about. One of these, Cuthbert Mireling, lived right opposite to the old ladies’ home, and another, Gilly Ponstock, had rooms at the local pub where Richard Luckery used to drink, sometimes with one of his aunt’s gardeners, Albert Giggs.

On a Saturday in June, Miss Lucia said at lunch that she was going to spend the afternoon taking cuttings of pinks and pansies in one of the borders. The gardeners would have gone home and she liked having the garden to herself. In fact, she never missed her Saturday afternoon’s gardening.

Agatha asked her nephew to wheel her out on the terrace from which she would be able to watch her sister. This he did, then went up to his own room for a sleep.

At about half-past two, in full blazing sunlight, Miss Agatha was horrified to see a man walk furtively out of the shrubbery with a heavy bar of wood and crash it down on her sister’s head. The first blow may have been enough to kill her, but he struck again and again.

Miss Agatha screamed, but it was some minutes before Katie, the only servant then in the house, came running out and a few minutes more before Richard Luckery appeared. He seemed rather dazed, and said afterwards that he had been asleep.

Miss Agatha then did something which shocked and astounded the servant. She turned to Richard in great horror and shouted, ‘Keep away from me! You killed Lucia!’

Richard protested: he had been upstairs. His aunt was hysterical, he said. He was as shocked as she was. Then he told the servant to telephone for a doctor. The old lady would not be left alone with Richard. It was some time before she became coherent enough to tell the servant exactly what had happened.

By now people began to gather. Giggs, the gardener, whose cottage was across the stable yard, appeared and Cuthbert Mireling arrived at the front door, having heard the screams from his home. A doctor was sent for and so was I, and between us we examined Miss Lucia, who was quite dead, and managed to calm her sister a little.

It was not until the evening, however, that I could get a statement from her. I had been over the ground by then and seen that the murder had happened about 200 yards from the terrace and that it was possible to reach the shrubbery from the house without being visible from where Miss Agatha had sat. Or, as I thought, to reach the house from the shrubbery for that matter.

The first thing that Miss Agatha said was that her nephew must be arrested at once.

‘I saw him do it!’ she kept repeating.

I pointed out that it was 200 yards away and asked how she could be sure.

‘I watched him. He was wearing his deerstalker hat and that cape of his.’

‘But did you see his face?’

She would not or could not give a clear answer to that question. She knew it was Richard. She could see him quite clearly. The cape … the hat … it was Richard. I was to arrest him; not leave him in the house with her. Question her as I might, I could get no more from her.

Then I tackled the nephew. Before lunch he had been in the local pub playing darts with his two friends and Giggs, the gardener. He had left his aunt on the terrace and gone upstairs to sleep. He had heard the screams and come down. He could not account for Miss Agatha’s accusations.

When I asked him about the Inverness cape he said he had found a stuffy little outfitter’s shop in London which had some old stock of things long out of fashion—spats, fancy waistcoats, Norfolk suits and these capes. He gave me the name and address. He said that he had thought it would be amusing to wear something so dated. Yes, his friends knew where he had purchased it. I asked him to go and fetch it, and he did so, but took a long time over it.

‘Katie had it,’ he explained. (Katie was the servant.) ‘She was mending a tear in it.’

There was no sign of a stain or anything unusual about the thing.

I sent for Katie and found out, as I half-expected by then, that she had taken the cape to her room after lunch that day to repair it and that it had actually been in her hands while the murder was committed.

It was easy to understand which way the case was developing now, and when I went to the little shop and found that they had sold two of these Inverness capes in the last few months I could see daylight. The shopkeeper could not help me much over the two purchasers. He remembered the first fairly well and his description fitted Richard Luckery, but about the second he was uncertain. He remembered it was a young man, but nothing much more except that he had seemed in a hurry.

Next, of course, I cross-examined the two friends, but neither of them had much of an alibi. Cuthbert Mireling had been at home reading, he said, in a deck-chair on the lawn when he had heard screams coming from the old ladies’ house. He had gone across to see what was the matter and whether he could be of any help. Gilly Ponstock had remained in his room at the inn asleep. He knew nothing about the murder till he came down to tea at half-past four and was told by the innkeeper. The gardener had been alone in his cottage.

It was a puzzler. Someone had bought one of these capes with which to impersonate Richard Luckery, had put it on in the shrubbery, murdered the old lady and made off. Giggs and Mireling had some sort of motive because each had fair-sized legacies, Giggs as an old employee, Mireling as a son of old friends. Either could have done it, but there was not a shred of real evidence against them.

My wife said that case would be the death of me. I couldn’t sleep for worrying over it. I’d tried all the ordinary things that should have provided clues—fingerprints, footprints, the weapon used, but none of them gave me an inkling. If I ever commit murder, I said, it will be like this, in the open where everyone can see me do it. Then I know I’ll never be found out.

Then suddenly I had an idea. I searched Richard Luckery’s room, then came downstairs and arrested him. He was charged, tried and, I’m glad to say, in due course hanged.

The explanation? Well, he had found what he thought was a very clever way of committing murder. A double bluff. He decided to impersonate someone impersonating him. Perhaps it was by chance that he came on that old stock of Edwardian clothes, or perhaps he was actually looking for something of the sort. He chose that Inverness cape as a garment easily distinguishable, bought another with which to impersonate himself, made a habit of wearing the first one, then waited his moment. He chose a Saturday afternoon because he knew that Miss Lucia would be gardening then, asked Katie to mend his first cape, went down to the shrubbery where he had hidden the second, put it on, murdered his aunt and returned to the house, which he entered while the servant was on the terrace. He had a perfect witness in Miss Agatha, who would swear it was him, because of the cape, and a perfect alibi in that his cape would be in Katie’s room. He knew I should soon find out about the purchase of the second cape by someone who did not resemble the purchaser of the first—some simple disguise, I guessed. The more Agatha swore it was him, the more sympathy he would gain for being impersonated.

But, of course, he made his one mistake. They all do, thank heavens, or I don’t know what would become of detectives. He forgot to plan the disposal of the second cape. I found it between the mattresses on his bed.

LEO BRUCE

Rupert Croft-Cooke, who wrote detective fiction under the pen name of Leo Bruce, was born in 1903. He was brought up in south-east England, an aesthete in a family of athletes, and attended Tonbridge School and what is now known as Wrekin College in Shropshire, where he did well both academically and at the game of darts, at which he excelled.