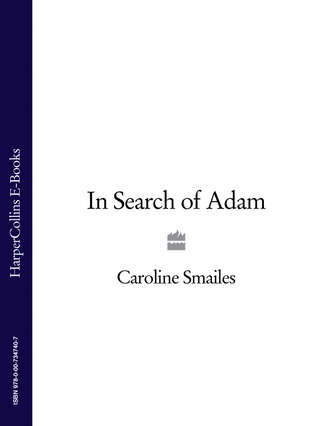

Полная версия

In Search of Adam

I stood. Blood and wee slid down to my white ankle socks. He had lit a fire inside me. My hair was matted with sand. My blue school blouse was ripped. I was seven years two months and twelve days old.

I walked out onto the beach. It was quiet. It was dark. Too dark. The lighthouse was still. No eye. No yellow eye. No green and orange little men. No one was watching. I climbed the one hundred and twenty steps. I did not touch the green handrail that wove next to the steps. I had to keep stopping. Doubled in pain. Difficult to breathe. Difficult to carry on. I walked myself over and along the main Coast Road. The lollipop lady had gone home. I walked past the Dewstep Butchers that doubled as the New Lymouth Post Office and displayed a garnished pig’s head in the window. Past New Lymouth Primary School. Past New Lymouth Library. Past Brian’s Newsagents. Stretched across 127-135 Coast Road. Past the detached homes which housed the professional types. I walked to my mother’s house. Eyes never looking left or right. I hoped that a car would hit me. I walked slowly. I had ripped clothes but my brown parka covered them. I had a single line of blood trickling down my inside thigh. Inside my brown parka. I was covered in sand. Nobody stopped me. Nobody asked me what had happened. People looked away. Neighbours called their children in from play. Nobody. Nothing.

A greedy decision. A need for shiny fifty-pence pieces. A greedy need. I was saving to buy a globe. One that lit up with the flick of a switch. Paul Hodgson (Number 2) had gotten one last Christmas. I needed fifteen pounds. That was a lot of money. A greedy need. Misguided trust. My whole life stepped onto a path. I stepped onto a path. I sometimes imagine that my palms were smooth and blank. Right up until that week. That precise week. That my palms had promise. I still had a future. That I still had exciting challenges and a glossy journey ahead of me. With my decision. With my greedy need. The lines appeared. Abracadabra. Hey presto. The lines were engraved. Tattooed. Forever. Scraped in a web of complications. My palms told of the self-destruction that lay ahead.

I never bought the globe.

Sand

In my pants.

Itchy itchy sand monster.

Sand

In my tummy.

Sand

In my head.

Nasty nasty sand monster.

Sand

Make me vomit.

Sand

Make me die.

Naughty naughty sand monster.

Never to be gone.

Dirty dirty sand monster.

I used my key. It was tied to a piece of string and fastened with a safety pin inside my brown parka. I fumbled with the pin. My hands were shaking. Sand and blood poked from the tips of my nails. I was dirty. Sand clung in between my fingers. Dirty dirty dirty. I needed to wash my hands. I needed to scrub and scrub and make my hands clean again.

I let myself in. Wiped my feet on the welcome mat and slowly climbed the ruby carpeted stairs. Each tiny footstep sent a flame up my inner thigh. Rita and my father were in the kitchen. My movements were slow. I wanted them to come out. I wanted them to see my pain. I had no voice. Eddie had stolen my voice. I could not speak. No energy. No power. Slowly. Slowly. Slowly. A tiny skulking mouse. Pain flicked with each step. My father shouted a hello and then turned his attention back to Rita. They did not come out to me. She was giggling again.

Alone in the bathroom. I took off my school uniform. Blood damp socks and ripped school shirt. I neatly folded my soiled clothes and placed them beneath the radiator. A perfect pile.

Undressed. Exposed. Naked in the centre of the small square room. Too late to cry. I did not cry. I had not cried. Big girls don’t cry. Do you hear me? Big girls don’t cry. My father and Rita had moved into the lounge. I could hear their laughter. The cackles and giggles and boom boom booming. They were drinking from their tin beer cans. Their laughter glided up the red stairs and squeezed under the locked bathroom door. Their joy rebounded between the ceiling and linoleum floor.

Bounce

bounce

bounce

bounce.

As I stood stark naked. In the centre of the bathroom.

I faced the bathroom cabinet. Focused on a perfect thumb print smeared on the bottom right hand corner of the mirror. I forced my eyes to fix on the girl who was hidden beneath that smudge. Through the smears. I stared into myself. I saw my blue eyes. My mother’s blue eyes. I stared at my matted brown hair. Dirty dirty hair. I needed the sand off me. Get off me. Get off me. Nasty nasty sand. It was everywhere. It was swallowing me up. I opened the bathroom cabinet. I took out a pair of scissors. They were sticky and blunt. I tugged at my hair.

Chop.

Chop.

Chop.

Clumps fell into the sink. A nest of hair. Grooming and nurturing collected and then plunged. Congealed feathers over onto the linoleum floor. I didn’t have my mother’s skill. Long strands clung to my gluey fingers, mingled with the knotted blood and sand. I needed to be rid of the sand. I wanted it off my skin. I wanted it out of my hair. It clung. Sticky sticky sand. I yanked. I tugged. It had climbed my hair and grafted onto my scalp. I wanted to scream. I wanted rid. Get off me. Off off off.

I turned the chrome taps. Hot and cold. I waited in the centre of the room. I climbed into the pea green bath. The water was cold. Rita had used all of the hot water. Rita liked a hot bath. The bath had not been cleaned. An orange ring clung to the slippery sides. I climbed in. I gasped. I was numbed. Pain pain go away. Pain pain go away. I lay stiff. I was rigid. Straight. Head bobbed. Ears submerged into the rising cold. Muffled reality. Frozen sounds. Arms stiff. Blue feet. I dared not move. Sand began to sink onto the bottom of the pea green bath. Floating in my sea. Sailing in my dirt. Away away for a year and a day. I drifted. I danced by the light of the moon.

The water needed to enter me. To wash away his dirt. I stung. The fire roared. I dared not move. I could not let the water in. The fire roared. And roared. And roared. Tiny white body. Flat and smooth. A swarm of bruises erupted from my veins. Gobbled up my skin. Decorated my secret places. Pain pain go away.

I heard my father calling. I sat to attention and listened. He was going to the pub with Rita. A swift half. Then they would be back. A swift half and then I would tell him all about Eddie. I had to tell him. I didn’t understand why, but I knew that it didn’t feel right. I needed my father to make everything better. He would know what to do. Too many secrets. Hush hush. My head was pounding. Whirling. Swirling. Round and round. Twirling secrets round and round. Hush hush.

Again. My father called. I wasn’t to open the door to any strangers and I could have some chocolate from the fridge. It was Rita’s chocolate, but I could have some. Just that once. Four squares. They were in a hurry to get to the pub. Meeting Mr Johnson from Number 19. Just a swift half. Don’t open the door to any strangers. Did you hear me Jude? I didn’t know what a stranger was. Surrounded by neighbours. No strangers in Disraeli Avenue. No need to fear strangers. I was alone. All alone. I was naked in the bath. I was seven years, two months and twelve days old.

My father and Rita went out. I heard the door. Slam.

He left me all alone. I needed him and he had left me. I needed someone to make me better. I needed someone to explain the pain. I needed someone to make that pain go away. Pain pain go away. This wasn’t how it was supposed to be. Slam and alone. Fear attacked the veins in my toes. I stayed upright. Bolted within the bath. Shivering. Blue. Trembling. Shuddering. I was alone. The house suddenly seemed so big. So empty. So still. Cold. So cold. I was terrified that Eddie would come back. He would be watching them leave. He would know that I was alone. He would enter my mother’s house. I was naked in the bath. I would be trapped. He would kick down the door. He would hurt me. Aunty Maggie had a spare key. He could let himself in. I wouldn’t be able to stop him. Help me. Help me. Help me.

I was sick into my bath.

Sand and sick mingled. Dirty dirty bath. I dried myself. Delicate touches made me gasp in pain. Numbness faded and my secrets flared. I dressed ready for bed. Purple pyjamas covered with cream teddy bears in purple boots. Father Christmas had left them for me on Christmas Eve. I had been on the good list. I would not go to bed. I wanted to wait for my father. I needed to wait and ask him about Eddie. Slowly, I moved down the stairs. Tiny steps caused cascades of pain to rumble in my tummy and tumble down my inner thighs. I sat on the bottom red stair.

Through the frosted glass panel on the green front door, I watched the darkness stumble down to the ground. I saw the streetlamp flame. I waited for shadows. Then. I hid in those shadows. I watched the twinkling star. In sight of the frosted panel of glass. I was a guard. A quivering sentry. I waited.

I heard my father. He was singing as he walked and Rita’s pixie boots click clacked a rhythmic beat. I heard them coming. He had had his swift half. He was happy. I had not turned the light on. I was rooted on the bottom red stair. Alone in the dark. My nails dug into my palms, but my knuckles were fixed. I concentrated through the pain. So much pain.

Spain…France…Scotland…

America…London…

Libya…

Malta…

Tibet…

Victoria…

Boston…

Greenland…

Spain…

France…

Scotland…

America…

London…

Libya…

Malta…

Tibet…

Victoria…

Boston…Greenland…Spain…France…Scotland

…America…London…Libya…

Malta…

Tibet…

Victoria…

Boston…

Greenland…

Spain…

France…

Scotland…

America…London…

Libya…Malta…

Tibet…

Victoria…

Boston…

Greenland…

What are ye doin in the dark ye silly bairn?

My father broke my journey. I didn’t say that I wanted Eddie to think that I was out. I didn’t say what Eddie had done to me in the cave. My voice had not returned. I had been waiting to tell my father about Eddie. I needed my father to explain my throbbing. I was crying. Big girls don’t cry. Only whinnying bairns cry.

My father saw my hair. He was staring at my hair. I had forgotten. I had forgotten about the nest of hair. On the linoleum floor. Rita laughed at me. Rita said it was sweet. My wanting to be a hairdresser like my dead mother. My father got angry. He said that my mother was an evil whore. He said that I was a whore’s brat and then he slapped my ear. Buzz fuzz. I was sitting on the bottom red stair. I turned and dashed up those stairs. As fast as I could caper. He caught my ankle and pulled me down. My chin counted each step. One two three four five six. He pulled down my pyjama pants and he slapped me five times. Rita was cackling. As she exhaled the room was filled with stale fumes. Invading. I could smell their swift halves. He pulled me up and twisted me over. He slapped my face. An erupting sting peaked and lingered. He yelled. Loud. In my face. In my ear. No brat o’ mine could be s’ fuckin strange. I looked down to the floor. I could still feel his palm on my cheek. Pain. More pain. I focused on a tiny swirl woven into the carpet. I had never noticed it before. Not until that moment. That precise moment. Snot and tears twirled together at the tip of my chin and gently dripped onto the ruby fitted carpet, just missing the peak of that perfect swirl. I counted six drips. Drip

drip

drip

drip

drip

drip.

The carpet absorbed them. My father went into the kitchen and Rita staggered after him.

I stayed. Feet rooted to the hallway carpet. Alone. Rita wobbled back struggling with a glass basin. Rita would fix my hair. She put the empty fruit bowl on my head. She cut around it. Her fingers never touched my hair. The scissors scratched and slashed. When she had finished, she removed the bowl. She chuckled. She said that I looked like a boy. She wasn’t my mother. She had a funny smell. She pinched my arm. It hurt. More decoration. She whispered just loud enough for me to hear. Evil brat just like ye killer of a mam. I hated Rita. She was fat and ugly. She was not like my mother. She was a nasty nasty beast. I didn’t like the way she looked at me. Her eyes were angry. Little piggy stare, with lines and lines exploding from them. Lines buried in her skin. Lines that made her look angry and sad and mean and ugly. She was never happy. She was not my mother.

My hair looked silly. I looked silly. My pain bubbled inside. I ached and I ached. I went to my room. I lay on my blue bed. Reached under my pillow. I took my mother’s blouse. I held it to my face. Her scent was gone. I held it to my chest. I slept.

Hoping.

Eddie went away. He had been a guest. How nice of him to visit. He came for a week. He ripped me. It’s oor little secret. You’re me special girlfriend. Here’s an extra fifty pence. Nobody noticed. On Monday. Three days later. I went to Aunty Maggie’s house. She was mad. She was all shouty. Eddie said I had run away on the beach. I was a rude little girl. She did not give me a fifty-pence piece. I was angry. I needed that fifty-pence piece. Saving to buy a globe that lit up with the flick of a switch. Eddie was such a nice man. A real gent and the perfect house guest. He would visit again soon. I was a naughty girl. It’s oor little secret. No one would believe a bairn like yee. Tell anyone and I’ll get yee. I didn’t say anything. Eddie had stolen my voice.

I never bought the globe.

Timothy Roberts (Number 21) was in my mother’s house. Rita was on the phone. Talking to Mrs Clark (Number 14). Rita was talking about Mrs Roberts (Number 21). Mrs Roberts had to go to the hospital. Had a woman thing wrong with her. She asked Rita to babysit Timothy. Just for a couple of hours. Timothy Roberts was two and a bit of a bugger at times. Timothy Roberts was emptying the kitchen cupboards. Banging pans onto the floor. I went to see him. Stood at the kitchen door. I listened while I watched him.

Apparently. Mrs Roberts (Number 21) had had a bit of Mr Johnson (Number 19). They lived next door to each other. Their garages joined onto each other. During the day, lazy arse Mr Johnson would nip round for a bit of how’s ya father. I didn’t understand. Apparently. Mrs Johnson was blind as a fuckin bat to what was going on right under her nose. I didn’t understand. Apparently. Mr Johnson and Mrs Roberts were taking the piss. Rita said that she’d been staring at the brat for the last twenty minutes and couldn’t figure out who the bugger was like. She reckoned that he was either Mr Dewstep the butcher’s, Mr Johnson’s or possibly Mr Scott’s (Number 25). I didn’t understand. Rita was laughing. Cackling. She thought it funny that Mr Johnson was pulling a fast one expecting to get away with fiddling on his own doorstep. She was telling Mrs Clark (Number 14) that Mr Johnson would be caught with his pants doon. I didn’t understand.

I stood in the kitchen doorway. Watching Timothy Roberts bang bang banging. I was staring and staring at him. Waiting for Mr Dewstep. Waiting for Mr Johnson. Waiting for Mr Scott. Waiting for the three men to step out of Timothy Roberts. I really didn’t understand.

Rita had changed her yackety yack yack yarning. She was talking about Karen Johnson now. A reet pretty bairn. She was telling Mrs Clark (Number 14) all about Karen’s accident. I’d seen it happen. I knew what had happened. I’d watched it from my bedroom window. Karen Johnson had been roller skating. Up and down. Up and down. Up and down the street. She had new skates. They were red and had huge rubber stoppers at the toe. I liked them. I really liked them. Anyway. Karen Johnson had fallen over. Apparently she had slipped on some crap or other that the lazy arse bin man had dropped. I didn’t know. I had seen her fall. I had watched her land on her hand.

Snappety.

Snap.

Snap.

Apparently. You could have heard her screams in Wallsend. I heard them through my bedroom window. I saw them escape from her mouth. All the neighbours came rushing and pushing to help. Emergency. Emergency. Help. Help. Help. I saw Mr Johnson. He came flying over the other neighbours. He was faster than a speeding bullet. He was faster than an aeroplane. He was faster than the wibble wobblers. Rita was telling Mrs Clark (Number 14) the story. Apparently. Mr Johnson flew in the air like fucking Superman. Mr Johnson was Superman. He had scooped Karen in his arms and ran all the way back to his house. From just outside Number 4 to Number 19. Rita was laughing again. Cackle cackle cackle. I wouldn’t mind suckin on his super power. Cackle cackle cackle. I didn’t understand.

Karen Johnson was taken to hospital. Mrs Roberts (Number 21) had given Mr Johnson and Karen a lift. Dirty buggers. Cackle cackle cackle. Apparently. Karen Johnson had been a reet bravebairn. Her wrist had snapped in two places. Snappety snap snap. Poor bairn. She had a white plaster cast on her arm. I saw her from my bedroom window. I had seen her every day for the last four. She sat on her front wall. Clutching her white plaster. Clutching it as it changed colour. One two three four days. All the neighbours stopped to talk to her. All the neighbours wrote their names. Some drew pictures. I saw the colours. I saw the squiggles. But. But I never wrote my name. Mrs Roberts (Number 21) took her sweets. Mrs Shephard (Number 15) bought her a little teddy bear. Karen Johnson kept them all with her. All her new things. Along her front dwarf wall. A reet pretty bairn. A reet brave bairn.

Timothy Roberts started screaming. Piercing. Shrilling to the ceiling. He had hurt his eye. Hit it with a wooden spoon. Rita was angry. Rita had had to end her natter. Her yackety yacking cut short. She stormed past me. Slapped my head. Sharp. Sting sting sting. Fucking useless ye are. Can’t be fucking trusted te look after a little bairn. Timothy Roberts stopped crying. He stared at me. He was sad. He was angry. I had let him be hurt.

Inside me

Thousands of your waste

Swim.

Penetrating, burrowing,

Tails wiggling,

Worming into my essence.

You forced them into me

And now I exist with part of you.

I long to turn my insides out,

To scrub,

Till blood-filled scabs replace the dirt.

I have become you.

We remain one,

Till death us do part,

Till your dirty thousands die with me.

I hurt inside. I felt sick. I had a strange feeling that was with me all the time. It made me breathe faster. It made me feel as if something bad was about to happen. In the days and then weeks following my walk with Eddie, I began to hear noises. I heard voices. I jumped with fear. I shook. I was cold. Everything was inside of me and it needed to come out. It needed to escape from me.

The neighbours weren’t always there after school. Eleven months and one day since my mother’s death and I was known to be a reet strange bairn. They said it was alright for me to be alone. They liked me to be on my own. They found me odd. She’s strange, that Jude. It was a Tuesday evening and I didn’t go to Mr Johnson’s (Number 19). I used my key instead.

Rita came to my mother’s house before my father got home from work. She cooked his tea and ironed his shirts. She wanted to marry him. She wanted to live in my mother’s house. She always came at the same time. Number 28 bus from Wallsend to Marsden. Arrived at 4.45pm or 5.15pm depending on which one she caught. I had sixty minutes. She had a key.

I went into my father’s garage. It was attached to the house, through a wooden door from the kitchen. The stone floor was cold. I felt the cold through my white ankle socks. I looked around. The walls of the garage were my father’s. Shelves of goodies and racks of tools. Half empty cans of paint. Brushes. Turpentine. Buckets. Jars of screws. Tins of nuts and bolts. Rakes. Brooms. Hammers. Screwdrivers. Saws. Spades. Never just one of a sort. I saw a tin. A pretty tin. A navy blue cylinder. It had a gold trim and EIIR in gold lettering. It was dusty. It was neglected. It was too special to be on a shelf. In my father’s cold garage. My father liked his garage. His special things were kept there.

The bricks of the garage were damp. It stank of the oil which had leaked from the bottom of my father’s yellow Mini. A pool of oil was in the centre of the stone floor. A rusting lawn mower slumped against the wall waiting to be cleaned. I was looking for something to help me. I was standing in the doorway, scanning the room for something. Something to help me.

A paintbrush. Too soft.

A spade. Too heavy.

A hammer. Just right.

I took down a hammer from my father’s tool rack. It looked very old. A thick dull metal head, with a wooden handle covered in scratches and dents. It spoke of experience. It was heavy and cold. I went back into the kitchen.

The kitchen. A rectangle that was divided into two separate areas. One where you ate. One where you cooked. When the house was empty I sat in that area where we used to eat. Special occasions. Christmas Day. Ripped-open Selection boxes. Chocolate for breakfast. A Curly Wurly poking out, waiting to be sneaked before lunch. Turkey dinner. Snapping crackers. Paper hats and funny jokes. Toon Moor night. Fish and Chips from the chippie on the seafront. Eaten straight from the newspaper parcel. Placed onto a plate. A bag of candy floss saved from the fair. Fluffy, pink and promising to be delicious. Easter Sunday. A leg of lamb, roast potatoes and lashings of mint sauce. Easter eggs lined up on the kitchen worktop. In sight and waiting.