Полная версия

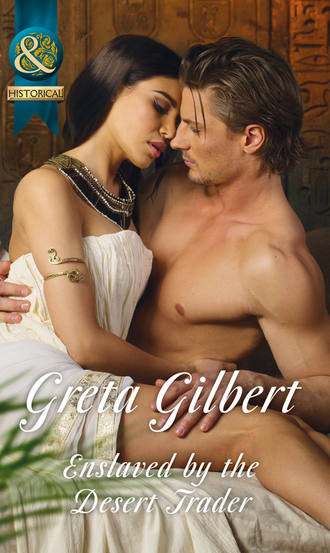

Enslaved By The Desert Trader

‘Today, the Libu tribes have taken back only a small part of what we are owed,’ he concluded.

Tahar felt the hairs on the back of his neck stand on end. What was the purpose of this tirade? They had raided the Great Pyramid of Stone and taken hundreds of lives, along with a large haul of grain and three sacred bulls. Was that not enough?

The Libu raiders raved and howled, passing the wine bags between them as the full moon rose. When a bag was finally handed to Tahar he only feigned taking a draught. He had struggled his entire life to be accepted as Libu, but as he watched the men rally behind their bloodthirsty Chief he realised that he did not want to be. Nor did he have to be—thanks to the woman who stood silently in the shadows, pretending to watch the moon.

Chapter Six

It felt almost pleasurable, at first—that flick of a tongue across her thigh. That cool, soft skin pressing against her calf. She tried not to move, tried not to breathe. Perhaps this was only a dream.

Then she heard it—a soft, almost imperceptible hiss, like the sound of fire consuming grass. She worked to free her hands, but she could not. Tahar had tied them before she had fallen asleep. Nor could she jump up—he had bound her ankles too. She felt the movement of the creature’s skin on her leg. This was no dream. This was the certainty of death, twisting up her body like a rope.

Another serpent.

Kiya lifted her head. There was Thoth, the Moon God, his face round and full. In his powerful light she could see all the men. They sprawled around the dying embers of the fire, sated with wine. Their cacophony of contented snores burned Kiya’s ears and filled her body with hatred.

Thieves. They did not deserve to rest so well—not with so many innocent lives on their hands. Yet as she watched the serpent disappear under her wrap, it seemed that it was Kiya whom the Gods wished to be punished.

This was not an accident, as she had believed the viper to be. This was her mother’s prophesy unfolding. Beware the three serpents, she had warned Kiya, so long ago.

If the viper had been the first serpent, then this asp was surely the second. Or was it? A water snake had swum by them in the oasis pool. It had veered towards her, then veered away, deterred by a brush of Tahar’s hand. If the water snake had been the second serpent, then this asp was the third. Perhaps this was not the continuance of her mother’s prophesy, but the fulfilment of it.

But why? Why did the Gods wish Kiya dead?

Suddenly it came to her. The tomb. She should have never heeded King Khufu’s call to service. She should have never gone to labour upon his Great Pyramid of Stone. Instead she should have listened to the priests, whose message was clear: no female should ever set foot upon a tomb. She had broken the taboo. Now the Gods were merely exacting their punishment upon her.

Kiya resolved not to fight the asp. She would face her death bravely, for it was the Gods’ will. She took the part of her headdress that she had placed under her head and stuffed it into her mouth. To cry out would mean to wake her captors, and she refused to give them the pleasure of witnessing her death. She slowed her breathing and braced herself for agony.

Then she felt it—the sting of two sharp fangs in the tenderest part of her thigh. The exquisite pain crackled through her body, followed by a kind of squeezing inside her that made her breath grow short. She studied Thoth’s pocked white face, which seemed to grow larger, closer.

Her strength drained away and the needling pain in her thigh grew. She had failed her people, who asked only that she revere the Gods, that she heed their simple rules. Soon she would face Osiris, the King’s heavenly father, in his Hall of Judgement—though she probably would not even make it that far. She had no papyrus to tell her the names of the doorkeepers, nor any priest to say the spells. She did not even have any gold with which to pay the boatman.

Not that any of it mattered. She had sinned against the Gods. She was doomed to wander for all eternity in the labyrinths of the Underworld, lost as she had always been, among strangers.

Now the serpent’s figure slid into view, profiled against Thoth’s blurring face. The creature had climbed the entire length of her. Its hood expanded, it hovered above her, as if considering her transgressions. She would go now, willingly. She let her eyelids close.

But behind her eyes she found only darkness. She did not hear the howls of the jackals, who guarded the gates of the Underworld. Instead, she heard the sound of footsteps in the sand.

She could no longer feel her limbs, and the world began to spin. She heard a sharp hiss, and the rough scuffing of feet upon the ground. Then something else—a soft, wet noise, like the suckling of a babe at its mother’s breast. There was a strange tugging sensation at the site of the wound.

Was someone attempting to suck out the venom? Yes, it did feel as if there were a mouth tugging at her thigh. There was no time for reflection, for soon an acute pain ripped through the numbness in her leg. She had never felt such agony—not even when she had been pierced by the Libu blade. She opened her mouth to scream and felt a large hand over it.

‘Stay silent,’ the trader’s voice growled.

She bit down hard on the cloth again. The feeling of suction at the site of the bite returned, then ceased.

‘Tahar,’ sneered the Chief. He muttered something in the Libu tongue, then bent over Kiya and switched to Khemetian. ‘What is wrong, slave?’ he asked.

Kiya felt the fabric of her headdress being arranged to cover her face.

‘The boy will not answer you,’ explained Tahar. ‘He has suffered the bite of an asp. He is all but dead.’

‘Are you alive, boy?’ asked the Chief, ignoring Tahar. Kiya stayed silent. ‘Let me see you.’ Kiya could feel the fabric of her headdress being tugged.

‘There is no need to look at the site,’ the trader explained steadily. ‘It is already too late to stop the poison.’ His voice was like the edge of a blade.

‘There is enough moonlight to at least see the mark,’ said the Chief. ‘Or would you deny my will?’

Kiya felt the cover come briskly off her face. She smelled the Chief’s strong, sour breath. ‘The boy still breathes,’ the Chief said. ‘If I can save him, Tahar, he is mine, for you have clearly forsaken him.’

Kiya felt her wrap being folded back, then a sudden sharp pain as the Chief’s finger probed the tender site where the asp’s fangs had penetrated her thigh. He pushed his hand further up, and she drew a breath when she felt Chief’s bony fingers discover her woman’s mound.

‘What is this?’ the Chief exclaimed. ‘Not a boy at all!’ The Chief yanked his arm from beneath Kiya’s wrap. ‘You have lied to us, Tahar.’

Kiya opened her eyes, but could see only shadows all around her. Her body was limp with exhaustion, but she felt a small tingling sensation returning to her legs, and the tightness in her chest had diminished. She saw the shapes of slumbering men stirring upon the ground. They growled and moaned, still heavy with the effects of the wine. The shadowy figures of two men stood above her, motionless.

‘If you give her to me now I will forgive you,’ whispered the smaller shadow—the Chief.

‘Never. She is mine.’

‘She is ours,’ the Chief said, his voice growing louder. ‘She is a spoil of the raid. She belongs to every man here.’

‘Nay, she belongs to me and me alone.’

What happened next Kiya wasn’t entirely sure. She felt her limp body being scooped into the trader’s strong arms. She was placed atop the horse and felt the trader’s large, warm body slide behind hers. He gripped her tightly by the waist.

‘Do not fight me,’ he whispered with hot breath. ‘Not now.’

As they rode away she heard the frantic sound of the Chief’s shouts. Though she did not speak the Libu tongue, she could imagine what he was saying.

‘Why do you delay, you drunken fools? Get her! She is ours!’

Chapter Seven

‘I am yours, My King. You may take me if you wish,’ breathed the young woman. She had draped herself across King Khufu’s lap, as she had been instructed, though she could not bring herself to relax her limbs.

‘I wish you would get off my legs,’ said the King. ‘You are stiffer than a mummy.’

The woman scrambled to the floor and waited obediently upon her knees.

‘Just rub my feet, woman,’ the King bristled.

The King’s newest concubine took his soft right foot in her hand and began to knead. ‘You are the handsomest, most magnificent king who has ever lived,’ she said as she worked, for concubines were trained to flatter the King in such ways.

‘Indeed?’ answered King Khufu, bemused. He plucked a grape from the fruit basket on the table and stared out at the brown rooftops of Memphis.

‘And the most intelligent and the most powerful and...’ The woman paused.

‘And?’ asked the King.

‘And the most accomplished.’

‘Ah! Accomplished. Did you hear that, Imhoter?’ The King pointed a shrivelled date at his elderly advisor, who was kneeling at the foot of the King’s divan.

‘Yes, My King,’ said Imhoter, keeping his head bowed.

Of course the holy man had heard it. He had been kneeling with his head bowed for some time, waiting for the King to release him from his obeisance.

‘Do you think she refers to my ossuary, Imhoter?’ asked the King. ‘You know—that little building I made?’

‘Yes, Majesty,’ Imhoter intoned, studying the lapis tiles beneath his knees. ‘That is the structure to which I believe she refers.’

‘Is that it, coddled one?’ the King asked his concubine. ‘You refer to my heavenly catapult?’

The beautiful young woman ceased rubbing his foot, utterly confused. After several moments the King’s lips narrowed into an angry line. He pointed his royal finger north.

‘Oh!’ the woman exclaimed. ‘Yes, My Lord, the Great Pyramid of Stone. Yes, yes. That is the accomplishment to which I was referring. It is truly...awe-inspiring. Future generations will look upon it with...awe.’

The King wrenched his foot from the woman’s hands. ‘You bore me, young blossom.’ He turned to the priest. ‘Imhoter, remind me to send a teacher to the Royal Harem. A historian, and perhaps a scribe versed in the embellishments of language. These new concubines are as thick as palm trunks.’

‘Yes, Majesty,’ said Imhoter, keeping his gaze upon the floor.

‘Well, get up, then, Imhoter!’ the King said finally. ‘Or am I surrounded by fools?’

Imhoter stood slowly, glancing sidelong at the young woman. Her eyes had been kohled with an elegant, swirling design, but tears now threatened to smudge the lovely black circles.

The King levelled an icy stare at the woman. ‘And get a special tutor for this one. This...’ The King paused. ‘Pray, what is your name?’

‘Iset, My King,’ said the woman.

The setting sun shot a golden ray across the terrace and lit up her ochre-red lips, which trembled like a child’s.

‘Iset,’ Khufu said. ‘Even the name is dull.’

A single tear traced a path down the woman’s powdered cheek. Imhoter knew that the woman had been preparing her entire life for this—her first encounter with a Living God. As his concubine she would share his bed, would bear his bastards, yet up until this moment he had not even bothered to learn her name.

Imhoter watched the woman wither beneath the King’s gaze. The King did not know her name, and neither would any man, for the life of a concubine was foremost the life of a loyal servant. She would live out her days in the seclusion and isolation of the harem—available for the King whenever he wanted her, alone and lonely when he did not.

This was the fate of all concubines—glorious and terrible. Imhoter could not understand why women went so eagerly towards it. In his fifty years of service to the King, and the King’s father before him, there had been only one concubine who had resisted that fate. Imhoter’s heart squeezed and he pushed the memory from his mind.

Now Iset wiped her tear and gestured meekly towards the King’s foot. ‘Shall I continue, My King?’ she asked.

‘Tsst!’ the King hissed, brushing her away.

If only Imhoter could tell the poor woman that the King no longer welcomed any woman’s touch. Indeed, it was well known amongst King Khufu’s priests and advisors that he hadn’t taken either of his wives nor any of his concubines to his bedchamber in many, many moons.

‘Leave me now,’ the King spat at the woman. ‘Go!’

She jumped up and rushed across the expanse of the terrace, the train of her long white tunic dragging behind her like a sail unable to catch the wind. Imhoter could hear her sobs as she disappeared behind a distant column.

It was another ill omen, for the mark of a king was his virility—his ability to fertilise the land of Khemet with his seed, which he was expected to plant in as many concubines as possible. In that particular function King Khufu had lately begun to falter. The younger priests were already scandalised by the King’s behaviour. They whispered among themselves like harem girls. Has Horus Incarnate lost his virility? That was the question on their minds, for the King’s body was Khemet’s body, and for two years Khemet had been suffering a drought.

‘Do not condemn me, priest,’ the King growled, reading Imhoter’s thoughts. ‘Am I not the Living God? Can I not do what I please, my actions reflecting the will of Horus, God of Order and Protector of both Upper and Lower Khemet?’

The King lifted his empty goblet, and a slave boy holding a large pitcher emerged from the shadows and filled it.

‘Of course, Majesty,’ Imhoter said.

‘Then open your mouth, eunuch,’ the King commanded, reminding the former priest of his debased status, ‘and tell me why you have come.’

A rush of shame pinched Imhoter’s chest, but he did not show it. Instead he reminded himself of his duty to Khemet. He had faithfully advised King Khufu’s father, Sneferu, and now he served Khufu himself.

He took a deep breath and began. ‘Keeper of Khemet, I had a most compelling vision as I slept this morning. It involved your House of Eternity, the Great Pyramid of Stone.’

Khufu nodded, squinting at the glowing white pyramid at the horizon’s edge. To reach it required a day’s journey from Memphis, but even at this great distance the building appeared powerful, impermeable, eternal.

Still, Imhoter could not help but feel a growing sense of dread. It had been two years now since Hapi, the life-giving flood, had blessed the land of Khemet with its waters. And now akhet, the season of the flood, was almost over. If Hapi did not arrive soon there would be no crops again this year. Without any reserves left, the people of Khemet would slowly begin to starve.

‘Tell me, Imhoter. What did you see in your vision?’ the King asked.

‘I saw an army of men clad in violet and blue. They seemed to be bursting out of the sun itself. Some ran; others rode donkeys. They were running towards the Great Pyramid of Stone.’

‘Libu?’

‘Aye. It appeared to be a raid, though I did not see more than what I have said...’ The priest paused.

‘What else, Imhoter?’

‘Nothing, Majesty.’

‘I know there is something else,’ Khufu said, and His Majesty was right. The King read Imhoter like a scroll. ‘Tell me, Seer, for the Gods speak to me through you.’

‘As you wish—but this part of the vision confuses me,’ continued Imhoter. ‘I also saw a woman. She was a beautiful woman, as splendid as the Goddess of Love and Abundance herself. Two black serpents hung from her temples. They touched her collarbone like strands of hair. You commanded that she be sacrificed.’

‘Sacrificed? It is not since the time of Zoser and the Seven-Year Drought that a human has been sacrificed.’

‘That is why I do not understand the vision. I know that Your Majesty would never return to that barbarous ancient practice.’ Imhoter swallowed hard. In his haste to placate the King he had divulged too much of his vision. Now he could see Khufu turning the idea over in his mind.

‘What did she wear, this sacrifice?’

‘She wore golden serpents on each of her arms and legs.’

‘Did you see anything more in your vision? Did you see Hapi, our precious flood? Is it coming at last?’

‘No, I am afraid I saw nothing to do with Hapi.’

‘Nothing at all?’

‘Nothing at all. Just a legion of Libu...and a lady of serpents.’

Just then a King’s Guardsman appeared at the far end of the terrace. The Royal Chamberlain announced the man’s arrival as he strode the length of the space and prostrated himself at the foot of the King’s divan.

‘I bring urgent news for the ears of the Living God.’

‘Speak,’ commanded the King.

‘Your Majesty, I was sent by Hemiunu, Chief Vizier and Overseer of the Great Pyramid, just before he perished.’

‘Perished?’ The King’s goblet made a loud clang as it fell upon the tiles.

‘Yes, My King, along with most of the King’s Guard. A Libu horde attacked the grain queue early this morning. Lord Hemiunu bade me tell you. It was his dying wish.’

‘And the grain?’

‘It is all gone—stolen by the Libu filth.’

The King cast an awestruck gaze at Imhoter, then sat back.

Imhoter could not believe the guardsman’s words. The grain tent had contained the last of the royal grain stores. Now the tomb workers would have nothing to help them see their families through the drought.

‘The lady of serpents,’ muttered the King vacantly.

‘Your Majesty?’ said the guardsman.

‘A woman wearing golden serpents upon her wrists,’ the King said, ‘did you see her?’

‘No, My King, I am sorry. There were no women at the raid.’

The King sank back into his cushions and it appeared to Imhoter as if he had shrunk to half his size. ‘And Hapi, our magnificent flood?’ the King muttered, the colour draining from his face. ‘When will it arrive? When?’

Chapter Eight

There was and there was not. That was how Kiya began all her tales. It was the traditional way, the way of the entertainer. It was the way her mother had taught her, for concubines were expected to provide diversions for kings, and stories were one of them.

Kiya remembered few details from her mother’s tales, but she remembered how her heart had swelled as her mother had described worlds beyond Kiya’s wildest dreams—worlds in which animals talked and people did magic and everything came in threes, including wishes.

After she’d lost her mother and gone to live on the streets of Memphis, Kiya had often loitered outside the taverns, where men told tales for money and fame. Her aim had not merely been diversion: there had often been food to be had, as well. Kiya would huddle undetected under the kitchen windows behind the taverns, hoping to filch a half-eaten honey cake to fill her stomach and catch a story to sustain her.

There was and there was not, the storytellers would begin, and she would strain to hear their fantastic falsehoods—stories of giant crocodiles and shipwrecked sailors and men who lived for hundreds of years. The storytellers’ words would transport her to places far beyond the dusty streets of Memphis, and for a short time she’d feel worldly. Not an orphan, but a traveller. Not a street beggar, but a princess. The storytellers carried harps and, for the right amount of beer they would sing and play. Kiya always smiled when they sang her favorite song, ‘The Laundry Woman’s Choice,’ about a poor laundry woman who must choose between two suitors. ‘I will wear the shirt I love best, no matter how it fits’ went the chorus, and Kiya would quietly sing along.

She was fascinated by the bond the storytellers called love. She longed to feel it. She had searched the faces of the young men in the marketplaces, and as her womanhood had begun to bloom they had searched her face in return. But they had always looked away.

Slowly, Kiya had begun to realise that she was not desirable to young men. And why should she be? She had no family or property—not even a proper tunic or wig. She clad herself in rags and grew her own hair, which hung in tangled ropes that smelled vaguely of the docks.

One day Kiya had been digging for clams in the shallows of the Great River when an old man had approached her. His gait had been crooked, and Kiya had been able to smell the sour, vinegary aroma of wine upon his breath.

He’d grabbed her by the arm. ‘You are mine now, little mouse,’ he had slurred.

He had already torn away most of her ragged wrap by the time her teeth sank into his flesh.

She’d bitten down hard, unaware that it would be the first of many such bites. As she’d run away she had remembered her mother’s words: Stay away from men, Kiya! They only mean to possess you, to enslave you.

How right her mother had been. As she’d got older the menace of men had only grown. She’d needed protection, and had been confronted with the choice all street girls faced: to sell herself into servitude or to sell her body in a House of Women.

Kiya had not wanted to choose. Each time she’d considered the options she had felt her ka begin to wither. She had meandered through the marketplace and splashed in the Great River, desperately clinging to her old life. She had lingered outside the taverns, listening to the storytellers’ tales, remembering the urgency of her mother’s words and trying to conceive of another way.

Finally, she had: shaving her head, concealing her curves and covering herself in rags, just like a character in a story.

Kiya had became Koi.

There was and there was not.

* * *

‘Awake!’ a deep, familiar voice commanded.

But when she opened her eyes darkness enveloped her still.

‘I have arrived in the Underworld?’ she stuttered.

There was a menacing chuckle. ‘If you consider a cave in the banks of an ancient river the Underworld, then, yes, indeed. You have arrived.’

Kiya’s head throbbed. ‘I am...alive?’

‘Yes, you are alive—though you have been sleeping the sleep of the dead for many days.’

The air around her was cool and still, and her eyes could discern nothing in the inky darkness. Layers of cloth swaddled her, but beneath them was a hard surface. She attempted to sit up, but a searing pain shot through her inner thigh and she collapsed back onto the ground with a curse.

‘Don’t forget that you have been bitten by a deadly asp,’ said the voice from somewhere close. ‘And pierced by a Libu blade.’

She touched the tender wound on her arm. Where had that come from? A confounding fog stifled Kiya’s thoughts. Where was she? And what menace stalked her now? She needed to find a weapon—a stone, even a handful of dirt would suffice. A desperate thirst seized her and she coughed.

‘Nor should you forget that you drank from an oasis pool,’ the voice added. ‘You have been vomiting for two days.’

‘And still I am not dead?’

‘Your Gods apparently wish you alive.’

‘Nay. I am certain they wish me dead.’

‘Well, you are fortunate to know me, then, for I have saved you from their will.’

‘And who are you who would thwart the Gods?’

‘You do not remember?’

‘I scarcely remember who I am,’ Kiya moaned, for she was no longer Koi, the stealthy street orphan, nor was she Mute Boy from Gang Twelve of the Haulers. She was someone else entirely—someone positively new. But who?

‘In your fever you raved of serpents,’ said the voice.

Kiya heard the sound of stones being placed upon the ground.

‘Three serpents would try to take your life, you said. One would succeed, unless you become like...’

‘Like what?’ Kiya asked.

‘That was all you said.’

‘I heard a voice in the desert,’ she remembered. ‘A prophesy.’

‘If you heard such a voice in the desert, then it was no prophesy. It was an illusion—a waking dream. Illusions occur in the Red Land when a person lingers too long in the sun.’ A ray of sunlight flooded into the cavernous space. ‘Now, let there be light.’