Полная версия

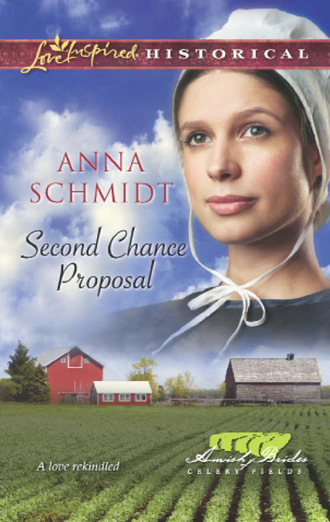

Second Chance Proposal

“Warmer today,” Roger said. “After the last spell of frosty mornings I thought we might be in for a stretch of cold weather.”

“Good for the crops that it’s passed,” replied the blacksmith, who was sipping a cup of coffee. He was a quiet man, as John had observed earlier that morning when the blacksmith handed Gertrude a box of kitchen items that Greta had gathered from her own supply to place in the rooms above his business. The idea of this silent giant of a man married to the vibrant and petite Greta made John smile.

A few minutes passed while the men discussed weather and crops and business. Then Bishop Troyer crossed the street from the dry-goods store and joined them.

“Bishop Troyer,” Roger said as he stood and offered the head of their congregation his chair. “Did you speak yet with John Amman?”

“Yah. We have spoken already twice. I am convinced that he has learned the error of his ways and come home to make amends,” the bishop replied. “Everything seems to be in order for tomorrow’s service.”

“Then I can have him working the counter come Monday.” This was not a question but something John realized his uncle had been dreading.

“Should bring you a bunch of business,” Luke said with a chuckle. “Folks will want to get a look at him after all this time. They’ll be curious about where he’s been and all.”

“They can look all they want at services. On Monday I need him to be working, although I’m not sure how we’re going to have enough business to support the three of us.”

“I seem to recall that this entire matter had its beginning in John wanting to start a business of his own,” Bishop Troyer said.

Roger let out a mirthless laugh. “With what? He has nothing. Gert had to buy him the clothes he’s wearing now and he owes a debt of gratitude to Luke here that he has a place to stay.”

“Still, he must have a skill if the plan was to open his own shop.”

“He’s a tolerable woodworker,” Roger allowed. “Clocks and furniture mostly. He built that cabinet where Gert keeps her quilting fabrics. And the clock we have in the store—that’s his work.”

John saw the bishop exchange a look with Luke. “I reckon Josef Bontrager took up that business in John’s absence,” Luke observed.

Roger stared out at the street. “You’ve got a point there. Not much call for handmade furniture these days.”

Was it John’s imagination or had his uncle raised his voice as if to make sure John heard this last bit of information? It hardly mattered. He was in no position to take up his trade. Over the past several months he had sold off his tools one by one or bartered them for a meal or a night’s lodging.

“Well, until something comes along he’s got work with you. The Lord has surely blessed him in having you and Gertrude still here,” the bishop said.

“Speaking of work I’d best get back to it,” Luke said as he drained the last of his coffee.

As the bishop took his leave and Roger walked slowly back to the hardware store, John stepped from the shadows of the storeroom into the sunlight that bathed the loading dock. There was work to be done—a pile of newly delivered lumber that his uncle had instructed him to sort and stack by size and type in the pole shed outside the store. But when he stepped into the yard he heard feminine laughter coming from the rooms above the livery.

He took a moment to enjoy the sight of the women moving in and out of the apartment, up and down the outside stairs carrying various items they seemed to think he might need. Then Lydia came out onto the tiny landing at the top of the stairs to shake out a rag rug.

She was laughing at something one of the other women had said, her head thrown back the way he remembered from when they’d been teenagers. And in that laughter he heard more clearly than any words could have expressed exactly why he had decided to return to Celery Fields. He had come back to find answers to the questions that had plagued him. He had come back to the only place where he knew there was a path to forgiveness and from there a safe haven to rest in while he found his way. He had come back because even eight long years had not erased the memory of this girl turned woman whose laughter had always had the power to stir his heart.

Chapter Three

When Lydia glanced up and saw John watching her from the loading dock, the laughter she’d been sharing with the other women died on her lips. How could she possibly have gotten so caught up in the pleasure of the work and companionship with the others that she had been able to forget that he was back in her life, whether she wanted it or not? That the place the women were scouring and setting to order was where John would live—was already living? How had she forgotten who would be eating off those mismatched dishes that she had washed and dried and stacked so precisely on the open shelf above the stove?

She had helped scrub the walls and floors and even made up the narrow bed that occupied one corner while engaged in the normal chatter. At events like this, women enjoyed catching up on news from families that had moved back north when the hard times hit, or the decision of the newest member of their cleaning party and her husband to move to Florida and start fresh after a tornado had destroyed the family’s farm in Iowa. And so the morning had passed without a single thought about John Amman. His presence in town was far too recent and their encounters had been rare enough that it was easy to lose herself in the work and the conversation. It was truly amazing how easily she had been able to simply dismiss the man from her mind.

But now seeing him standing in the back doorway of the hardware store, filling the space with his tall, lanky frame, she could not seem to stop the images of him living in that small apartment from coming. He would rinse the dishes she had washed for him at the sink as he looked out the small square window with its view of her house. He would hang his clothes on the pegs that she had wiped free of dust above the bed. He would sleep in that bed under a quilt that Greta had brought to add an extra layer to the one already there. It was a quilt that Lydia and Greta’s grandmother had made. A quilt that had once covered the bed Lydia and Greta shared when they were children.

She felt the heat rise to her cheeks as these images assailed her and John stepped closer to the edge of the dock, his bold gaze fixed directly on her. The other women went about their work, glancing shyly in his direction as their laughter and discussion dissolved into expectant silence. Lydia stood frozen on the steps, her fingers gripping the small rag rug until her knuckles went white. She felt as if her cheeks must be glowing like two polished red apples.

Greta stepped onto the porch landing next to her. “He’s watching you,” she whispered.

Hilda Yoder cleared her throat. “We have more work to do,” she instructed with a glance at John and then a lift of her eyebrows to Lydia. “Greta, take this mop bucket and get us some clean rinse water.”

“I’ll do it,” Lydia said firmly. Greta had no business hauling buckets of water up and down that steep staircase.

“I hardly think that...” Hilda began but then pressed her lips into a thin line and said no more.

Lydia handed the rag rug to Greta and took the bucket. She descended the stairs without looking at John, but she knew he was following her every move. Dumping the soapy water, she set the bucket aside and prepared to prime the pump until the faucet spit out fresh water. Above her she knew Hilda Yoder was watching with disapproval. She saw John leap down from the loading dock and walk slowly toward her. She could not help feeling a little like the sandpiper she’d once seen caught in a fisherman’s abandoned net at the beach.

She reached for the pump handle but John was there first, his fingers closing around the handle and brushing hers. “Let me,” he said softly. Lydia snatched her hand away as if she’d gotten too close to a hot stove. Then, not knowing what else she might do, she looked away while he primed the pump until the faucet squirted clear water into the pail.

Without a word he carried the full, heavy pail up the steps and set it on the landing careful to keep his eyes lowered so as not to give offense to any of the women Hilda had herded quickly inside. His delivery complete, he hurried back down the steps, past Lydia, who had waited in the yard, and back to the loading dock where he turned his back to them and began sorting through a lumber pile of mixed-size pieces.

“That man has been too much out in the world,” Hilda Yoder huffed as Lydia mounted the steps and all the women went back to their work.

“It may take him some time to settle back into the old ways,” Pleasant said with a glance at Gert, who was clearly embarrassed by her nephew’s action. “After all, he has been eight years in their world. Still, the important thing is that he has seen the error of his youthful decision and come home to us.”

There was a general murmur of agreement among the women. But Lydia had her doubts that John would ever truly return to their ways. The only reason he’d come back now was because he’d clearly had nowhere else to turn. In Celery Fields he could be assured of forgiveness and the care of the community. From what she knew of outsiders, they were not quite so generous to those who were down on their luck. No, she knew John Amman perhaps better than any of them or, at least, she had once a long time ago. It simply was not possible for a man to change so completely, was it? To have finally learned his lesson and abandoned the wanderlust of his youth? To be satisfied at last with the quiet, simple life of his Amish roots?

“Hilda, you don’t think there’s any possibility for someone to vote against him tomorrow, do you?” Greta asked, her eyes wide with worry.

“John Amman has sought his forgiveness from Bishop Troyer,” Pleasant reminded Greta. “We will wait to hear his recommendation tomorrow.”

“Nevertheless, the congregation has to be unified in its acceptance,” Hilda reminded them. Lydia saw Gert Hadwell press her fist to her mouth. She hoped, for Gert’s sake, that Hilda had not got it into her head to vote against John. Not that she would put it past the older woman. Hilda saw herself as carrying the standard for what was right in their small community. In many ways her opinion carried almost as much weight as the bishop’s.

But to Lydia’s relief Hilda positioned herself next to Gert in a gesture that could only be read as one of support as she glanced around the room. “I think we have done as best we can here.”

Gert smoothed the quilt on the bed and nodded. “It does look nice,” she said with a smile. “Perhaps,” she added wistfully, “with such nice quarters John will find his peace here.”

“Well, I’ll say one thing,” Pleasant announced. “It smells a good deal better than it did when we came in.”

All the women laughed as they gathered their supplies and trooped down the outside steps to the yard below.

All except Lydia.

She lingered to wipe the oilcloth that covered the small wooden table and glance around the room one last time. She told herself she was only making sure they had left none of their cleaning supplies behind. But she knew better.

In spite of the aroma of the strong lye soap they’d used, offset by the sweetness of the furniture wax, John’s essence filled the space. And as she closed the door behind her she recalled the scent of John—the sheer warmth of his nearness when he’d bent to take the bucket from her. A memory stirred, of him standing so close to her one time when they had gone to the beach together. That day he had smelled of the sun and the sea. And that was the day they had shared their first kiss. They had been fourteen years old.

A lifetime ago, she thought, shaking off the memory as she followed the others down the steps and into the lane where they said their goodbyes. Greta glanced back at her. “Coming to the house, sister?” she called.

“I’m a little tired,” Lydia replied. “You go on.” She was aware that John had paused in the sorting of the wood the minute she spoke. He did not turn around, but everything about his posture told her he was listening.

Greta hesitated then nodded. “All right. See you tomorrow then.”

Ah, yes, tomorrow. First, the services where John will no doubt be fully embraced back into the community. After all, forgiveness is the very foundation of our Amish faith. And later Samuel’s birthday party, Lydia thought. And John would be there for all of it. She drew in a deep breath and forced a smile. It had already been a long and difficult day but the events scheduled for Sunndaag promised to test her even further. “Yah, tomorrow,” she replied.

* * *

On Sunday morning John was awake well before dawn. He lay on the narrow bed beneath two faded hand-stitched quilts and thought about the bed he’d slept in as a boy in a room shared by his three brothers. Where were they now? Married with families of their own? And his sisters? He tried to imagine them all grown-up.

And his parents. Dat. Maemm. Did they think of him? Speak of him?

He rolled onto his side and watched the rays of sun creep through the window that looked out onto Lydia’s property, and his thoughts turned to the day before him. He was confident that the congregation would vote to accept the bishop’s recommendation of forgiveness. But what about Lydia?

So far she had given not the slightest sign that once the bann was lifted she would be willing to resume the friendship they’d once shared. If he was going to live here they would be neighbors at the very least. And, given the way the community’s population had shrunk over the years, they could hardly avoid spending time in each other’s company from time to time. There would be gatherings where they would both be present, like the birthday party for Greta and Luke’s oldest child. Maybe once the bann was lifted Lydia Goodloe would meet his eyes instead of averting her gaze. Or would she? He was certain that part of the way she’d been acting had to do with her thinking she would never see him again. And now that he was here she had no idea what to do.

Well, by this time tomorrow—in fact by later this very evening, when they all gathered at Luke and Greta’s for supper, he would have made clear that she could no longer use the excuse of his shunning for refusing to talk to him. The congregation would vote to accept Bishop Troyer’s recommendation for forgiveness and full reinstatement, for that was the way of his people. They would vote in his favor for his aunt’s sake even if they still had doubts about him. He had missed the traditions of his faith; never in all the years he was gone had he once been tempted to follow the faith of outsiders. Without question there were any number of good and pious people out there, but their ways were far too complicated for John to fully grasp. He liked the simple ways of his own people.

He had made a mistake in not coming home after he’d saved up the money that he needed. Instead, he’d allowed his business partner and friend to invest for him. He’d had no idea what a stock market was, but he had trusted his partner and been drawn in by pure greed at the prospect of doubling his savings in a short time with no work at all. Now he realized that he should have known better. The day he’d turned that money over to his friend was the day he’d realized that he had lost his way—his purpose in leaving Celery Fields in the first place.

But now he was back. He had returned for many reasons—to reconnect with his faith and his community was certainly something that had driven him as he made his way west across the state. He had missed his family, although with them moved north again there was little he could do about that for now. But he had also missed his neighbors and friends. And as hurt and upset as he had been with Liddy, he could not get her out of his mind. Every day as he made his way back to Celery Fields he had thought about her. Through pouring rain and cold, blustery nights when he had to sleep outside, he warmed himself by remembering the times they had spent together, the dreams they had shared, the plans they had made.

Now that he was back he was more confused than ever by her behavior toward him. There was the business of the white prayer kapp for one thing, and then she had barely said ten words to him. Of course, that could be explained by his being under the bann, but still as a girl Liddy had had little use for such rules if they got in the way of what she thought made more sense.

John kicked the covers off and sat up on the side of the bed. Liddy had always been stubborn. She had her opinion on almost any subject and not much tolerance for those who did not see things as she did. The two of them had always been alike in that way and it had caused them no end of arguments when their individual views on a subject differed. But seeing her these past few days since his return—being able to observe her for the most part without actually being able to talk to her—John’s impression was that she had changed. She was more like her half sister, Pleasant, than she’d been as a girl. Then she had been as light-hearted as her younger sister, Greta. But from what he’d observed she had developed the pursed lips and tense posture of their former teacher—a woman Liddy had declared she would never ever want to emulate. But then there had been moments—like when he pumped the water for her—when she had glanced at him and he’d seen the girl he’d fallen in love with, the girl for whom he’d risked everything.

Well, that girl-turned-woman had some explaining to do. And once he’d gotten through the service and then the supper at Luke and Greta’s, he fully intended to find out why Lydia Goodloe had never acknowledged his attempts to write to her.

John stood and surrendered to the wide smile that stretched across his face. He raked his fingers through his thick hair and it flopped back over his ears, reminding him that he was once again Amish. In a matter of less than a week he had cast aside the trappings of the outside world and now presented himself as every other man in Celery Fields did. He knew one thing for certain: Liddy Goodloe had always been one who wanted to know exactly what to expect at all times. She liked being in charge. That was one of the things that made her a good teacher. Well, just maybe it was time the teacher became the student. And if anyone could teach her the lessons of surviving and even thriving on the unpredictability of life, it was John Amman.

He dressed and then prepared a hearty breakfast of eggs, fried potatoes and thick slices of Pleasant’s rye bread slathered with butter and jam. He set his plate of food on the table and bowed his head, thanking God for leading him back to this place and these people.

Anxious now for the day to begin, for this life he’d come back to retrieve to begin, John gobbled down his breakfast. He set the dishes in water to soak and was out the door and on his way to meet Bishop Troyer and the second preacher before the sun was fully above the horizon.

* * *

Usually Luke, Greta and the children called for Lydia early on Sunday morning. Services were held every other week in one of the homes that made up the community. On this day the service would take place in the Yoder house behind the dry-goods store in town and, as was her habit whenever the venue was so close, Lydia planned to walk. There was one problem, though.

To walk from her place to the Yoder house she would have to pass by Luke’s shop—and the residence of John Amman. Her plan was to delay leaving her house until she had seen him go. That way there would be no possibility of running into him. And so, dressed for over an hour already, the morning chores done, her breakfast eaten and her dishes washed, dried and back on the shelf, she waited. And waited.

The clock chimed eight and still there had been no sign of life in the rooms above the livery. She would be late. Greta would be worried, perhaps send Luke to fetch her. Everyone would be talking about her, about whether or not she had decided against coming because of John, about...

“Oh, just go,” she ordered herself.

She tied the ribbons of her black bonnet and wrapped her shawl around her shoulders. The morning air was still chilly although a soft westerly wind held the promise that by the time services ended she would have no need of the shawl’s extra warmth. She picked up the basket holding the jars of pickled beets and peaches that would be her contribution to the community meal that always followed the three-hour service. Then she stood at the door and closed her eyes, praying for God’s strength to get her through this day.

By the time she reached the Yoder house her sister had indeed worked herself into a state. “I thought perhaps you weren’t coming,” she whispered as she relieved Lydia of her basket and handed it to one of the Yoder daughters. “I know how difficult this—”

“I am here,” Lydia interrupted as she saw that most of the congregation had already taken their places in the rows of black wooden benches that traveled from house to house depending on where services were scheduled. “We should sit.”

Pleasant slid closer to the women next to her, making room for Lydia and Greta. She gave Lydia a sympathetic look, as did two other women who turned to look at her. Oh, will this ever end? Lydia thought even as she manufactured a reassuring smile of greeting for each of the women.

She and Greta had barely taken their places when the first hymn began. Lydia felt the comfort of verses that had been passed down from generation to generation for centuries as she chanted the words in unison with her neighbors. There was something so powerful in the sound of many voices chorusing the same words without benefit of a pipe organ or other musical support. By the time the hymn ended twenty minutes later Lydia felt fully prepared to face whatever the day might bring.

Of course, it helped that John was nowhere in sight. No doubt, he was sequestered in one of the bedrooms where the elders and bishop had met with him before the service. Either that or he had lost his nerve and run away again in the dark of night.

That thought gave Lydia a start. What if he had done exactly that? She struggled to focus her attention on the message as Levi Harnischer, the deacon of their congregation, preached. But as he rambled from one Biblical story to another she found her thoughts, as well as her gaze, wandering.

More than once she glanced toward the hallway that she knew led to the bedrooms. Was he there waiting to be called before the congregation to make his plea for forgiveness and reinstatement once the regular service ended?

Greta nudged her as the second hymn began and gave her a strange look. Are you all right? she mouthed.

Lydia frowned and nodded but Greta continued to stare at her.

“You are quite pale, Liddy,” she whispered.

“I am fine,” Lydia assured her, forcing a gentle tone through gritted teeth.

Bishop Troyer’s sermon followed the singing, and there could be no doubt of his message. He quoted the story of the prodigal son and then focused much of his attention on the young people seated in the front two rows of benches on either side of a center aisle. For over an hour he spoke of lambs wandering away from the flock, tempted by the promise of greener pastures. He spoke of the dangers that awaited such runaways and the importance of returning to the stability of the fold.

All around her Lydia saw her neighbors sitting up very straight as they listened with rapt attention to the bishop’s words. They knew what was coming. At the meeting following the service they expected John would enter the room and face them. Did not one of them entertain the notion that he might once again have lost his nerve and run away?

The final hymn began and as each verse was sung Lydia felt her heart beat faster. She focused her gaze on Gertrude Hadwell, who clearly could barely contain her joy at having John back in her life. If he left again, Gert would be devastated.

Please let him be here, Lydia prayed silently even as she understood that life would be far easier for her if John had surrendered yet again to the temptations of the adventures he’d found in the outside world.