Полная версия

Seduction And Sacrifice

Seduction and Sacrifice

Miranda Lee

www.millsandboon.co.uk

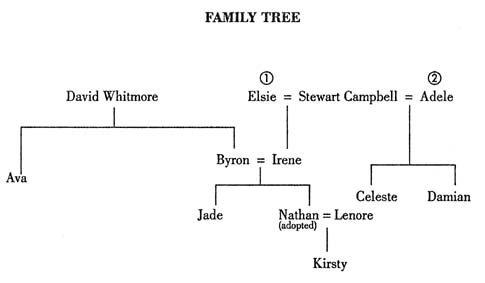

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS IN THIS BOOK

GEMMA SMITH: on her father’s death, Gemma discovers a magnificent black opal worth a small fortune and an old photograph that casts doubt on her real identity. In quest of the truth and a new life, she sets off for Sydney…

NATHAN WHITMORE: adopted son of Byron Whitmore, Nathan is acting head of Whitmore Opals and a talented screenwriter. After a troubled childhood, and a divorce, he is ruthless and utterly emotionally controlled.

LENORE LANGTRY: talented stage actress, ex-wife of Nathan Whitmore and mother of Kirsty. Lenore’s tough exterior hides her unrequited love for successful solicitor, Zachary Marsden.

KIRSTY: the wayward fourteen-year-old daughter of Nathan and Lenore has never come to terms with their divorce.

JADE WHITMORE: the spoiled, willful daughter of Byron and the late Irene Whitmore, Jade can’t have the one man she wants—her adopted brother, Nathan.

BYRON WHITMORE: recently widowed, Byron is the patriarch of the Whitmore family, and a stranger to love.

MELANIE LLOYD: housekeeper to the Whitmores, Melanie is emotionally dead since the tragic deaths of her husband and only child.

AVA WHITMORE: Byron’s much younger sister, Ava struggles with her weight, being unmarried and her fear of failure.

A NOTE TO THE READER: This novel is one of a series of six. Each novel is independent and be read on its own. It is the author’s suggestion, however, that the novels be read in the order written.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER ONE

SHE didn’t cry. Neither did anyone else attending her father’s funeral.

Not that there were many mourners standing round the grave-side that hot February morning at the Lightning Ridge Cemetery. Only the minister, Mr Gunther, Ma, and Gemma herself. The undertaker had left as soon as he’d dropped off the deceased. If you stretched a point, the grave-digger made five.

Admittedly, it was forty degrees in the shade, not the sort of day one would want to stand out in the sun for more than a few minutes unless compelled to do so out of duty. Gemma watched the coffin being lowered into the ground, but still she couldn’t cry.

The minister didn’t take long to scuttle off, she noticed bleakly, nor did Mr Gunther, leaving her to listen to that awful sound as the clods of dirt struck the lid of the coffin.

Why can’t I cry? she asked herself once more.

She jumped when Ma touched her on the shoulder. ‘Come on, love. Time to go home.’

Home...

Gemma dragged in then expelled a shuddering sigh. Had she ever thought of that ghastly dugout with its primitive dunny and dirt floors as home? Yet it had been, for as long as she could remember.

‘Do you want me to drive?’ Ma asked as they approached the rusted-out utility truck that had belonged to Jon Smith and which was now the property of his one and only child.

Gemma smiled at Ma, who was about the worst driver she had ever encountered. Her real name was Mrs Madge Walton, but she was known as Ma to the locals. She and her husband had come to try their luck in the opal fields at Lightning Ridge more than thirty years ago. When Bill Walton died, Ma had stayed on, living in a caravan and supplementing her widow’s pension by fossicking for opals and selling her finds to tourists.

She was Gemma’s neighbour and had often given Gemma sanctuary when her father had been in one of his foul moods. She was the closest thing to a mother Gemma had had, her own mother having died at her birth.

‘No, Ma,’ she said. ‘I’ll drive.’

They climbed into the cabin, which was stifling despite the windows being down. Bushflies crawled all over the windscreen.

‘What are you going to do now, love?’ Ma asked once they were under way. ‘I dare say you won’t stay in Lightning Ridge. You always fancied livin’ in the city, didn’t you?’

There was no use lying to Ma. She knew Gemma better than anybody. ‘I might go to Sydney,’ she said.

‘I came from Sydney, originally. Nasty place.’

‘In what way?’

‘Too big and too noisy.’

‘I could take a bit of noise after living out here,’ Gemma muttered.

‘What will you do with Blue?’

Blue was Gemma’s pet cattle-dog. Her father had bought him a few years back, fully grown, because he was a fierce guard-dog. He’d chained him up outside the entrance to the dugout and God help anybody who went near him. Gemma had rather enjoyed the challenge of making friends with the dog and had astounded both her father and Ma by eventually winning the animal’s total loyalty and devotion. The dog adored Gemma and she adored him. She didn’t have to think long over her answer to Ma’s question.

‘Take him with me, of course.’

‘He won’t like the city, love.’

‘He’ll like wherever I am,’ Gemma said stubbornly.

‘Aye, that he probably will. Never seen a dog so attached to a person. He still frightens the dickens out of me, though.’

‘He’s as gentle as a lamb.’

‘Only with you, love. Only with you.’

Gemma laughed.

‘That’s better,’ Ma said. ‘It’s good to hear you laugh again.’

Gemma fell silent. But I still haven’t cried, she thought. It bothered her, very much. A daughter should cry when her father died.

She frowned and fell silent. They swept back into town and out along Three Mile Road.

Both Ma and Gemma lived a few miles out of Lightning Ridge, on the opposite side to the cemetery, near a spot called Frog Hollow. It wasn’t much different from most places around the Ridge. The dry, rocky lunar landscape was pretty much the same wherever the ground had been decimated by mine shaft after mine shaft. Picturesque it was not. Nor green. The predominant colour was greyish-white.

Ma’s caravan was parked under a fairly large old iron-bark tree, but the lack of rainfall meant a meagre leafage which didn’t provide much shade from the searing summer sun. Gemma’s dugout, by comparison, was cool.

‘Come and sit in my place for a while,’ Gemma offered as they approached Ma’s caravan. ‘We’ll have a cool drink together.’

‘That’s kind of you, love. Yes, I’d like that.’

Gemma drove on past the caravan, quickly covering the short distance between it and her father’s claim. She began to frown when Blue didn’t come charging down the dirt road towards her as he always did. Scrunching up her eyes against the glare of the sun, she peered ahead and thought she made out a dark shape lying in the dust in front of the dugout. It looked ominously still.

‘Oh, no,’ she cried, and, slamming on the brakes, she dived out of the utility practically before it was stopped. ‘Blue!’ she shouted, and ran, falling to her knees in the dirt before him and scooping his motionless form into her lap. His head lolled to one side, a dried froth around his lips.

‘He’s dead!’ she gasped, and lifted horrified eyes to Ma, who was looking down at the sorry sight with pity in her big red face.

‘Yes, love. It seems so.’

‘But how?’ she moaned. ‘Why?’

‘Poisoned, by the look of it.’

‘Poisoned! But who would poison my Blue?’

‘He wasn’t a well-loved dog around here,’ Ma reminded gently. ‘There, there...’ She laid a kind hand on Gemma’s shaking shoulder. ‘Perhaps it’s all for the best. You couldn’t have taken him to Sydney with you, you know. With everyone but you he used to bite first and ask questions afterwards.’

‘But he was my friend,’ Gemma wailed, her eyes flooding with tears. ‘I loved him!’

‘Yes...yes, I know you did. I’m so sorry, love.’

The dam began to break, the one she’d been holding on to since the police came and told her that her father had fallen down an abandoned mine shaft and broken his stupid damned drunken neck.

‘Oh, Blue,’ she sobbed, and buried her head in the dog’s dusty coat. ‘Don’t leave me. Please don’t leave me. I’ll be all alone...’

‘We’re all alone, Gemma,’ was Ma’s weary advice.

Gemma’s head shot up, brown eyes bright with tears, her tear-stained face showing a depth of emotion she hadn’t inherited from her father. ‘Don’t say that, Ma. That’s terrible. Not everyone is like my father was. Most people need other people. I know I do. And you do too. One day, I’m going to find some really nice man and marry him and have a whole lot of children. Not one or two, but half a dozen, and I’m going to teach them that the most joyous wonderful thing in this world is loving one another and caring for one another, openly, with hugs and kisses and lots of laughter. Because I’m tired of loneliness and misery and meanness. I’ve had a gutful of hateful people who would poison my dog and...and...’

She couldn’t go on, everything inside her chest shaking and shaking. Once again, she buried her face in her pet’s already dulling coat and cried and cried.

Ma plonked down in the dirt beside her and kept patting her on the shoulder. ‘You’re right, love. You’re right. Have a good cry, there’s a good girl. You deserve it.’

When Gemma was done crying, she stood up, found a shovel and dug Blue a grave. Wrapping him in an old sheet, she placed him in the bottom of the dusty trench and filled it in, patting the dirt down with an odd feeling of finality. A chapter had closed in her life. Another was about to begin. She would not look back. She would go forward. These two deaths had set her free of the past, a past that had not always been happy. The future was hers to create. And by God, she hoped to make a better job of it than her father had of the last eighteen years.

‘Well, Ma,’ she said when she returned to the cool of the dugout, ‘that’s done.’

‘Yes, love.’

‘Time to make plans,’ she said, and pulled up a chair opposite Ma at the wooden slab that served as a table.

‘Plans?’

‘Yes, plans. How would you like to buy my ute and live here while I’m away?’

‘Well, I—er— How long are you going for?’

‘I’m not sure. A while. Maybe forever. I’ll keep you posted.’

‘I’ll miss you,’ Ma sighed. ‘But I understand. What must be must be. Besides...’ She grinned her old toothless grin. ‘I always had a hankerin’ to live here, especially in the summer.’

‘You could have your caravan moved here as well. Give you the best of both worlds. I won’t sell you Dad’s claim but you’re welcome to anything you can find while I’m gone.’

‘Sounds good to me.’

‘Let’s have a beer to celebrate our deal.’

‘Sounds very good to me.’

Gemma spoke and acted with positive confidence in Ma’s presence, but once she was gone, Gemma slumped across the table, her face buried in her hands. But she’d cried all the tears she was going to cry, it seemed, and soon her mind was ticking away on what money she could scrape together for her big adventure of going to Sydney.

Though a country girl of limited experience, Gemma was far from dumb or ignorant. Television at school and her classmates’ more regular homes in town had given her a pretty good idea of the world outside of Lightning Ridge. She might be a slightly rough product of the outback of Australia, living all her life with a bunch of misfits and dreamers, but she had a sharp mind and a lot of common sense. Money meant safety. She would need as much as she could get her hands on if she wanted to go to Sydney.

There were nearly three hundred dollars in her bank account, saved from her casual waitressing job, the only employment she’d been able to get since leaving school three months ago. She’d been lucky to get even that. Times were very bad around the Ridge, despite several miners reportedly having struck it rich at some new rushes out around Coocoran Lake.

Then there was Ma’s agreed five hundred dollars for the ute. That made just on eight hundred. But Gemma needed more to embark on such a journey. There would be her bus and train fare to pay for, then accommodation and food till she could find work. And she’d need some clothes. Eight hundred wasn’t enough.

Gemma’s head inevitably turned towards her father’s bed against the far wall. She’d long known about the battered old biscuit tin, hidden in a hole in the dirty wall behind the headboard, but had never dared take it out to see what was in it. She’d always suspected it contained a small hoard of opals, the ones her father cashed in whenever he wanted to go on a drinking binge. It took Gemma a few moments to accept that nothing and no one could stop her now from seeing what the failed miner had coveted so secretly.

Her heart began to pound as she drew the tin from its hiding place and brought it back to the table. Pulling up her rickety chair once more, she sat down and simply stared at it for a few moments. Logic told Gemma there couldn’t be anything of great value lying within, yet her hands were trembling slightly as they forced the metal lid upwards.

What she saw in the bottom of the tin stopped her heart for a few seconds. Could it really be what it looked like? Or was it just a worthless piece of potch?

But surely her father would not hide away something worthless!

Her hand reached into the tin to curve around the grey, oval-shaped stone. It filled her palm, its size and weight making her heart thud more heavily. My God, if this was what she thought it was...

Feeling a smooth surface underneath, she drew a nobby out and turned it over, her eyes flinging wide. A section of the rough outer layer had been sliced away to reveal the opal beneath. As Gemma gently rolled the stone back and forth to see the play of colour, she realised she was looking at a small fortune. There had to be a thousand carats here at least! And the pattern was a pinfire, if she wasn’t mistaken. Quite rare.

She blinked as the burst of red lights flashed out at her a second time, dazzling in their fiery beauty before changing to blue, then violet, then green, then back to that vivid glowing red.

My God, I’m rich, she thought.

But any shock or excitement quickly changed to confusion.

Her father had never made any decent strikes or finds in her various claims he’d worked over the years here at Lightning Ridge. Or at least...that was what he’d always told her. Clearly, however, he must have at some time uncovered this treasure, this pot of gold.

A fierce resentment welled up inside Gemma. There had been no need for them to live in this primitive dugout all these years, no need to be reduced to charity, as had often happened, no need to be pitied and talked about.

Shaking her head in dismay and bewilderment, she put the stone down on the table and stared blankly back into the tin. There remained maybe twenty or thirty small chunks of opals scattered in the corners, nothing worth more than ten, or maybe twenty dollars each at most. Her father’s drinking money, as she’d suspected.

It was when she began idly scooping the stones over into one corner to pick them up that she noticed the photograph lying underneath. It was faded and yellowed, its edges and corners very worn as though it had been handled a lot. Momentarily distracted from her ragged emotions, she picked up the small photo to frown at the man and woman in it. Both were strangers.

But as Gemma’s big brown eyes narrowed to stare at the man some more, her stomach contracted fiercely. The handsome blond giant staring back at her bore little resemblance to the bald, bedraggled, beer-bellied man she’d buried today. But his eyes were the eyes of Jon Smith—her father. They were unforgettable eyes, a very light blue, as cold and hard as arctic ice. Gemma shivered as they seemed to lock on to hers.

Her father had been a cold, hard man. She’d tried to be a good daughter to him, doing all the cooking and cleaning, putting him to bed when he came home rolling drunk, listening to his tales of misery and woe. Drink had always made him maudlin.

There were times, however, when Gemma had suspected it wasn’t love that kept her tied to her father. It was probably fear. He’d slapped her more times than she could count, as well as having a way of looking at her sometimes that chilled her right through. She recalled being on the end of one of those looks a few weeks back when she’d mentioned going to Walgett to try to find work. He’d forbidden her from going anywhere, and the steely glint in his eyes had made her comply in obedient silence.

A long, shuddering sigh puffed from Gemma’s lungs, making her aware how tightly she had been holding her breath. Her gaze focused back on the photograph, moving across to the woman her father was holding firmly to his side.

Gemma caught her breath once more. For the young woman appearing to resent her father’s hold looked pregnant. About six months.

My God, she realised, it had to be her mother!

Gemma’s heart started to race as she stared at the delicate dark-haired young woman whose body language bespoke an unwillingness to be held so closely, whose tanned slender arms were wrapped protectively around her bulging stomach, whose fingers were entwined across the mound of her unborn baby with a white-knuckled intensity.

So this was the ‘slut’ her father refused to speak of, who had died giving birth but who still lived within her daughter’s genes. Gemma’s father had told her once that she took after her mother, but other than that one snarled comment she knew nothing about the woman who’d borne her. Any curiosity about her had long been forcibly suppressed, only to burst to life now with a vengeance.

Gemma avidly studied the photograph, anxious to spot the similarities between mother and daughter. But she was disappointed to find no great resemblance, other than the dark wavy hair. Of course it was impossible to tell with the woman in the photograph wearing sunglasses. She supposed their faces were a similar shape, both being oval, and yes, they had the same pointy chin. But Gemma was taller, and much more shapely. Other than her being pregnant, this young woman had the body of a child. Or was it the shapelessness of the cheap floral dress that made her look as if she had no bust or hips?

‘Mary,’ Gemma whispered aloud, then frowned. Odd. She didn’t look like a Mary. But that had been her name on Gemma’s birth certificate. Her maiden name had been Bell and she’d been born in Sydney.

A sudden thought struck and Gemma flipped the photograph over. Written in the top left hand corner were some words. ‘Stefan and Mary. Christmas, 1973’.

The date sent Gemma’s head into a spin. If that was her mother in the photograph, pregnant with her, then she’d been born early in 1974, not September 1975! She was nearly twenty in that case, not eighteen...

Gemma was stunned, yet not for a moment did her mind refute her new age. It explained so much, really. Her shooting up in height before any other girl in her class. Her getting her periods so early, and her breasts. Then later, in high school, the way she’d always felt different from her classmates. She hadn’t been different at all. She’d simply been older!

Distress enveloped Gemma as she stared, not only at the date on the photograph, but at the Stefan part. Stefan had to be her father’s real name, not Jon. Lies, she realised. He’d told her nothing but lies. Why? What lay behind it all?

Gemma conceded she’d always suspected her father’s name of Jon Smith might be an alias. He’d been a Swede through and through, with Nordic colouring and a thick accent. But the opal fields of outback Australia was a well-known haven for runaways, mostly criminals or married men who’d deserted their wives and families, all seeking the anonymity and relative safety of isolated places. People did not ask too many questions around Lightning Ridge, not even daughters.

But the questions were very definitely tumbling through Gemma’s mind now. What other lies had her father told her? Maybe her mother hadn’t died. Maybe she was out there somewhere, alive and well. Maybe her father had stolen her as a baby, changed his name and lied about her age to hide them both from anyone searching for them. Maybe he—

Gemma pulled herself up short. She was grasping at straws, trying to make her life fit some romantic scenario like you saw on television, where a long-lost daughter found her mother after twenty years. Life was rarely like that. There was probably a host of reasons why her father had changed his name, as well as her age. He’d been a secretive man, as well as a controlling one. Maybe he’d thought he could keep his daughter under his thumb longer if she believed she was younger. Or maybe he’d simply lied to authorities about her age that time when they’d tackled him about why he hadn’t sent her to school yet.

Gemma could still remember the welfare lady coming out here to see her father. Despite her being a little girl at the time, and dreadfully shy, the visit had stuck in her mind because the lady had been so pretty and smelled so good. It was shortly after the social worker’s visit that Gemma had been sent to school. Her ‘birth certificate’ had surfaced a few years later when she had wanted to join a local netball team.

Gemma was totally absorbed in her thoughts when suddenly the sunlight that was streaming in and on to the table vanished, a large silhouette, filling the open doorway of the dugout. She froze for a second, then quickly shoved the photo and opal back and snapped the lid of the tin shut.

‘Anyone home?’ a familiar voice asked.

‘Oh, it’s only you, Ma,’ Gemma said, sighing as she stood up and walked forward across the dirt floor.

Her relief was unnervingly intense. For a split second, she’d been afraid her unexpected visitor might have been someone else. Which was silly, really. It had been six years and he hadn’t come near her, hadn’t even spoken to her when they’d passed on the street. There again, her father was no longer around to act as a deterrent.

And neither was Blue, she realised with a sickening lurch in her stomach. Oh, my God, was that who had poisoned her dog?

‘Come in and sit down, Ma,’ Gemma offered, trying to keep her steady voice while her insides were churning. ‘You’re just the person I need to see.’

‘Really? What about?’ Ma bulldozed her bulk over to the table and plonked down in a chair, which protested noisily.

‘I was wondering if you’d mind if I slept in your caravan tonight. I feel a bit nervous staying here on my own.’ Which was a huge understatement at this moment.

‘Do you know, that’s exactly what I came over here to see you about? I was thinking to myself that Gemma’s too good-looking a girl to be stayin’ way out here on her own. There are some none too scrupulous men living around these parts.’

Gemma shuddered, her mind whisking to one particular man, a big brute of a miner who had large gnarled hands and had always smelled of body odour and cheap whisky.

‘Well, I wouldn’t say I’m God’s gift to men, Ma, and I could certainly lose a pound or two, but, as you say, some men aren’t fussy.’

‘Lose a pound or two?’ Ma spluttered. ‘Why, girl, have you looked at yourself in the mirror lately? Maybe a few months ago you might have had a layer of puppy fat on you, but you’ve trimmed down this summer to a fine figure of a woman, believe me. And you’ve always had the prettiest face, though you should start usin’ some sunscreen on it. Mediterranean brown is all right for legs and arms but not for faces. You don’t want to wrinkle up that lovely clear skin of yours, do you?’