Полная версия

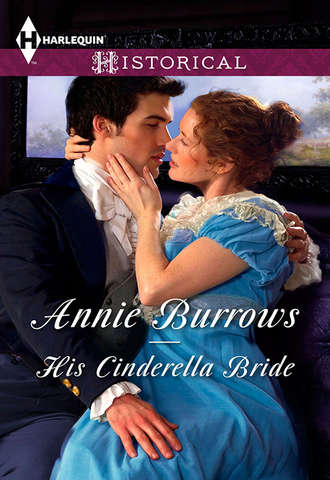

His Cinderella Bride

‘I thought you were the housekeeper,’ he grated.

Her head jerked up. For a second they looked straight into each other’s eyes, his contemptuous look heating her own anger to flash point.

‘And that excuses it all, does it?’ she snapped.

Feeling her uncle stir uncomfortably, she clamped her teeth on the rest of the home truths she would dearly love to spit at the vile marquis. She had no wish to embarrass her family by letting rip before they had even sat down to dinner. She contented herself by glaring at the tie pin that was directly in her line of vision. Her lip curled when she noted it was not a diamond, or a ruby, but only a semi-precious tiger’s eye. Provincial nobodies only rated the wearing of semi-precious jewels, even though he was one of the wealthiest men in England. His whole attitude demonstrated the contempt in which he held his prospective brides, from the curt tone of the letters he had written, right down to the tie pin he chose to stick in his cravat.

‘Ah, well,’ her uncle broke into the protracted silence that simmered between them, ‘Hester is of invaluable help to her aunt in the running of the house, especially when we have such a large influx of guests.’

‘I believe we have you to thank for arranging a most charming suite of rooms for us, Lady Hester,’ Stephen added gallantly.

To Lord Lensborough’s astonishment, Sir Thomas gave Lady Hester a hefty shove, which propelled her some three feet to her left, so that she was standing directly in front of Stephen Farrar while he made the introduction.

He continued to glare at her. She was angry with him, still. She had been clenching and unclenching her fists as though she would like to throw a punch at him. He conceded that she had some justification for that anger, considering he had subjected her to a couple of doses of language no well-born lady should ever have to hear, but he would never forgive her for snubbing him like this.

‘It is a pleasure to meet you,’ Stephen began, reaching out to take her hand. It was the opening gambit to the charm offensive he invariably launched against the fair sex, no matter what their age or condition.

Lady Hester whipped her hand behind her back before he could grasp it, never mind raise it to his lips, stepping back so abruptly she would have stumbled had not one of her cousins, Sir Thomas’s oldest married daughter, Henrietta, chosen that moment to drape her arm about her waist.

‘Come and sit by me, Hester darling,’ the heavily pregnant woman cooed. ‘You will excuse me, gentlemen? We have so much to talk about. Barny is cutting another tooth, you know.’

While the woman bore Lady Hester away in a flurry of silk skirts, Sir Thomas glared from Stephen to Lord Lensborough as though challenging them to make any comment on the extraordinary rudeness of his niece.

‘Odd kick to her gallop,’ he eventually conceded. ‘But for all that, she’s worth her weight in gold.’ He cleared his throat and changed the subject. ‘Well, now we’re all here, we can go in to dinner. You will escort my sister, Lady Valeria Moulton, of course, since she is the highest-ranking female present,’ he said to Lord Lensborough, turning to beckon the venerable lady to his side.

Stephen took the opportunity to murmur into his ear. ‘This just keeps getting better and better. We’re staying in a decaying labyrinth, populated by a family of genuine eccentrics—and to think I was afraid I was going to be bored while you clinched this very sensible match you claim to have arranged.’

‘And I never dreamed,’ Lensborough growled in retaliation, ‘to see a female back off in horror when confronted by one of your waistcoats.’

‘Ah, no. You have that quite wrong.’ Stephen ran a hand over the cherry-striped silk. ‘It was coming face to face with a genuine marquis that did for Lady Hester. She began to shake the minute she set foot in the room and you raised your left eyebrow at her.’

The Great Hall, to which the entire assembly then trooped, was, according to Lady Moulton, the Saxon thane’s hall around which successive generations of Gregorys had built their home. It certainly looked as though it could have been around before the Norman invasion. The exposed roof beams of what reminded him forcefully of a barn were black with age, the stone flags were uneven, and the massive oak door looked as though it could withstand an invading army. Mullioned windows were flanked by dented suits of armour, and he couldn’t help noticing that every single child that sat down at the refectory-style table was gazing round eyed at the impressive array of antiquated weaponry, from broad swords to chipped battle axes, which hung upon the walls.

Lady Moulton guided him to a seat near the head of the table, rather closer to the fire than he would have liked. In the event, he need not have worried about being excessively hot. Though the fire was large enough to roast an ox whole, and had probably done so on numerous occasions, the heat that emanated from it was tempered by the vast quantities of freezing air whistling in through cracked window panes and gaps under the doors. The faded banners that hung from the minstrel’s gallery fairly fluttered in the ensuing breeze.

Both Julia and Phoebe, who were seated opposite him, one on either side of Stephen, broke out in rashes of extremely unattractive goose pimples. Even he, in his silk shirt and coat of superfine, was grateful for the warming effect of the fragrant onion soup that comprised the first course. As footmen cleared the bowls away, he grudgingly revised his opinion of Lady Hester’s gown. Seated as she was at the far end of the table, among the children and nursery maids, it now looked like an eminently practical choice, given the arctic conditions that must prevail so far from the ox-roasting furnace. While he watched, she absentmindedly hitched a toning green woollen shawl around her shoulders, knotting the ends around a waist that appeared hardly thicker than his thigh.

‘Marvellous with children,’ Lady Moulton commented, noting the direction of his gaze. ‘Which makes it such a shame.’

‘A shame? What do you mean?’ For the first time since being partnered with the voluble dowager, he felt mildly interested in what she was saying.

‘Why, that she is so unlikely ever to have any of her own, of course.’ She addressed him as though he were a simpleton.

He quirked one eyebrow the merest fraction, which was all the encouragement Lady Moulton needed to elaborate. Once the footmen had loaded the board with a variety of roast meats, raised pies and seasonal vegetables, she continued, ‘You must have wondered about her when she was introduced to you and your charming young friend. Nobody could help wonder at such behaviour.’ She clucked her tongue as he helped her to a slice of raised mutton pie. ‘Always the same around unattached gentlemen. Crippled by shyness. Her Season was a disaster, of course.’

He dropped his knife into a dish of bechamel sauce. Shy? That hoyden was not shy. She had erupted from that ditch, her hair like so much molten lava, screaming abuse at the hapless groom he had sent to help her while he single-handedly calmed his nervously plunging horses by forcing them into a maneouvre that distracted them from their stress at having a woman dive between their legs while they had been galloping flat out. He had never seen a woman exhibit such fury. It was anger that had made her quiver in silence before him in the saloon. Anger, and bad manners.

‘She came out the same season as Sir Thomas’s oldest girl, my niece Henrietta.’ Lady Moulton waved her fork in the direction of the pregnant lady. ‘To save expense, you know. Henrietta became Mrs. Davenport—’ she indicated the ruddy-cheeked young man sitting beside her ‘—but Hester disgraced herself…’ She leaned towards him, lowering her voice. ‘Ran out of Lady Jesborough’s ball in floods of tears, with everyone laughing at her. She stayed on in London, but very much in the background. Got involved in—’ Lady Moulton shuddered ‘—charitable works. Since she has come back to Yorkshire she has made herself useful to her aunt Susan, I can vouch for that. But she will never return to London in search of a husband. Poor girl.’

Poor girl, my foot! Lady Hester was clearly one of those creatures that hang on the fringes of even the best of families, a poor relation. It all added up. The shabby clothes she wore, her role as a sort of unpaid housekeeper—for all that she had a title, she relied on the generosity of her aunt and uncle. And how did she repay them? When they brought her out, even though she could not fund a Season for herself, she had wasted the opportunity by throwing temper tantrums. Just as she abused their trust today by wandering about the countryside when she should have been attending to the comfort of her family’s guests.

‘You are frowning at her, my lord,’ Lady Moulton observed. ‘I do hope her odd manners have not put you off her cousins. They do not have the same failings, I promise you.’

No, he mused, flicking an idle glance in their direction, causing them both to dimple hopefully. Though it was highly unlikely they would ever become leaders of fashion, he was confident his mother could make either of them presentable with minimal effort.

Lady Hester, on the other hand, would never be presentable. Socially she was a disaster, was ungrateful to the family that had taken her in. He shrugged. No point in dwelling on a female he would be unlikely to see much of this week. Sir Thomas had stressed that it was only this one night, the first night of the house party, that egalitarian principles held sway. He turned to glare at her, just as she was shooting him a withering look. Face reddening, she turned to cut up a portion of the veal for a golden-haired moppet who was sitting beside her.

As he reflected with satisfaction that, come the morrow, servants, poor relations and children would be kept well out of sight, in the background where they belonged, a freckle-faced boy on her other side piped up, ‘Tell us about the pike, Aunt Hetty.’

‘Oh, dear,’ said Lady Moulton, reaching for her wine glass.

‘Yes, the pike, the pike,’ two more boys began to chant, bouncing up and down on the bench.

Lady Hester looked to her uncle, who raised his glass to signal his permission for the telling of the tale.

‘Well,’ she began, ‘there was once a man at arms, who served Sir Mortimer Gregory, in fourteen hundred and eighty-five…’

Lady Moulton turned to Sir Thomas. ‘Must we have these gory tales while we are eating, Tom? It quite puts me off my food.’

Perhaps she heard the complaint, for Lady Hester lowered her voice, causing the children to crane eagerly towards her, their little bottoms lifting from the bench in determination to catch every single word.

‘Family history, Valeria,’ Sir Thomas barked. ‘The young ones should know that the weapons hung about these walls are not merely for show. Every last one of ’em has seen action, my lord.’ He turned to address Lord Lensborough. ‘The Gregorys have been landowners in these parts through troublesome times. Had to defend our home and our womenfolk against a host of threats, rebels and traitors, and down through all the centuries—’

‘Never fought on the wrong side!’ Half a dozen voices from along the table chorused, raising their glasses towards Sir Thomas, who laughed in response to their teasing. Hester’s sibilant murmuring was drowned out by a collective groan of gleeful horror from the children. The tale of the pike had evidently come to its conclusion.

The golden-haired moppet crawled into Lady Hester’s lap, her blue eyes wide. As she curled an arm protectively about her, Lord Lensborough found himself saying, ‘Do you think it appropriate to scare such a young child with tales of that nature?’

He had not heard one word of the story, but from what others had told him, he judged it was as inappropriate as all the rest of her behaviour.

An uneasy silence descended upon the gathered diners when Lady Hester turned and met his accusing stare with narrowed eyes.

‘A girl is never too young,’ she declared, ‘to be taught what vile creatures men can be.’

Chapter Three

When the ladies and children withdrew, Lord Lensborough sank into gloomy introspection over his port.

Captain Fawley, a man who never minced his words, had told him to his face that he was a fool to be offended by the hunting instinct of single females who scented that, with Bertram dead, he would have to find a wife swiftly to secure the succession.

‘Women are mercenaries, Lensborough. The same shrinking violets that shudder at the sight of my face would steel themselves to smile upon a hunchbacked dwarf if he had money, leave alone a title. You are deluding yourself if you think you will ever find one who ain’t.’

It was depressing to accept that if he were to treat the Gregory females to the sort of language he had vented on the prickly Lady Hester, they would still fawn over him for the sake of getting their greedy little hands on his title. They were the same as all the rest. It appeared to be his destiny to marry a woman he could not respect.

He tossed back the rest of his port, reflecting that however much a man might kick against his fate, he was powerless to alter the final outcome. All he could do was bear himself with dignity.

So far today, he had not done so. His reckless mood had almost resulted in a woman being killed. True, she was not a pleasant woman, but he ought not to have let her make him forget he was a gentleman. When he had thought she was a beggar maid he had determined to ease her want with generous financial compensation. Now that he knew she was gently born, did he owe her any less?

Her position was one of dependence. Life for a poor relation could be well-nigh intolerable. She was vulnerable, and men of his station routinely abused such. Whatever she may have done, he needed to make her understand he was not of that fraternity. In short, he would have to make some form of apology, and it rankled.

* * *

There was precious little respite, Hester found, from the malign influence of the Marquis of Lensborough in the drawing room with the ladies. He was the prime topic of conversation, at the forefront of everyone’s thoughts. Even her own, she reluctantly admitted.

She had been all too painfully aware of his gaze boring malevolently into her throughout dinner, even though she managed to maintain a cheerful demeanour for the sake of the children.

He had sat at the head of the table, garbed head to toe in unrelieved black like some great carrion crow, waiting to pick over the shredded remains of her dignity.

She shuddered, trying to shake off such a fanciful notion. The marquis could not possibly know where she had been, or with whom, that afternoon. He disapproved of her, that was all, and why should he not? She had given him enough cause to despise her without him knowing the whole truth. Hadn’t she been out, unchaperoned? Hadn’t she physically assaulted his groom and shrieked at him like a fishwife?

Still, she huffed, he had never inquired how she was, never mind who she was. And he had the nerve to look down his nose at her?

She forced herself to smile and look interested as Henrietta chattered merrily away. How she wished she had the courage to flout convention and tell him to his face what a blackguard he was. But of course she hadn’t. Besides, she had to consider the repercussions. Firstly, she would make herself look like a hysterical ill-bred creature, while he, no doubt, would remain in full control. Perhaps just raising that left eyebrow in disdain, but that would be all.

Secondly, her aunt and cousins had already made up their minds to welcome him into the family, so eventually she would have to deal with him as a cousin by marriage. She had no wish to be barred from any of his homes. If he was as bad as she guessed, whichever of her cousins married him would soon find herself in need of moral support and she fully intended to provide it.

‘Of course, I can tell you don’t like him.’

Hester forced herself to pay attention. Henrietta could only be referring to Lord Lensborough.

‘No, I do not.’

Henrietta rapped her wrist playfully with her fan. ‘I shan’t take any notice of that. You have disliked every eligible male you have ever been introduced to. In fact, during our come-out, I used to think some of them quite terrified you.’

‘Some of them did,’ Hester admitted. ‘Most of their mothers did too.’

‘Oh, weren’t some of the patronesses dragons?’ Henrietta agreed with feeling. ‘And so cruel about your looks, as if there is anything wrong with having freckles and red hair. I do wish you could have found some nice, kind man who could have restored your confidence. You are not unattractive, you know, when you forget to be shy. If only you could have refrained from blushing quite so much, or stammering whenever a man asked you to dance.’

‘Or managed to control the trembling so that I could have got through a dance without tripping over my feet, I know. But I could not. And I would rather not hark back to that particular episode in my life. Altogether too painful. Besides, I am happy living here with your mama and papa. I don’t feel I am missing anything by not being married. In fact, on the whole, I would much rather stay single for the remainder of my days.’

‘You won’t let your shyness with them keep you away from us this week though, will you? Peter and I, and the children, would all be sorry if you hid yourself away altogether.’

‘I cannot even if I would.’ Hester sighed. ‘Your mama has strictly forbidden me to skulk, and your papa has backed her up.’

‘Quite right too.’

The door opened and the first of the gentlemen began to saunter into the drawing room. Phoebe and Julia scurried to the piano, hastily arranging the music they had been practising for this evening’s entertainment.

‘Oh, my. They’re doing it,’ Henrietta squealed, stuffing a handkerchief to her mouth.

‘Who is doing what?’

‘Lord Lensborough and Mr Farrar.’ Henrietta leaned closer and lowered her voice. ‘Harry told me how they are known for entering fashionable drawing rooms arm in arm, just as they are doing now, and of the stir it creates among the ladies present.’

Hester cast a withering look at her cousin Harry Moulton, who, as usual, had slouched to a chair at the farthest end of the room from where his rather faded-looking wife was sitting.

‘They call them Mars and Apollo,’ Henrietta continued. ‘The one broodingly dark, and the other sublimely fair, and both possessed of immense fortunes. Harry says the combined effect is such that he has known ladies to faint dead away.’

That was exactly the sort of tall story Harry would tell the impressionable Henrietta. Hester’s lip curled as she looked from one to the other as they lounged in the doorway, gazing complacently upon the assembled company. The arrogant black-hearted peer and the self-satisfied golden dandy.

She turned her head away abruptly as Lord Lensborough’s hard black gaze came to rest upon her.

‘Oh, my,’ Henrietta breathed. ‘Lord Lensborough is looking straight at you. With such a peculiar expression on his face. As if you’ve displeased him…oh, I expect it was the way you answered him back at the dinner table. You know, you really should not have spoken so sharply—whatever possessed you?’

‘I couldn’t seem to help myself,’ Hester confessed. ‘He just…’

Henrietta collapsed against her in a fit of giggles as Hester struggled for a reasonable explanation.

‘He brings out the worst in you—my, you really don’t like him, do you?’

* * *

Lord Lensborough gritted his teeth as he strolled towards the vacant seat beside his hostess. The ensuing conversation with Lady Susan hardly exercised his mind at all, leaving him free to wonder what Hester had just said, after looking at him with her lip curled so contemptuously, to make her companion collapse with laughter.

He managed to commend the accuracy of Julia’s playing, and compliment the sweet tenor of Phoebe’s singing voice whilst reflecting with annoyance that, while they were doing their utmost to impress him, it was their red-headed cousin that was uppermost in his mind. So intense was his irritation with her that he began to feel as if he was bound to her by some invisible chain. Whenever she moved, she yanked on that chain, drawing his attention to whatever she was doing. And she was always on the move, flitting from one group of chairs to another, seeing to the needs of the guests while their hostess lounged indolently beside him.

He took a deep, calming breath, taking himself to task. Wasn’t it a guiding principle for any horseman to get over heavy ground as lightly as possible? The woman was impossible, ill mannered, shrewish, all that was true. But it behooved him as a gentleman to apologise for his own part in their unfortunate first meeting. He would explain that he had initiated proceedings to reimburse her for her losses. Then it was up to her whether to accept a truce or continue hostilities.

When Sir Thomas called for some card games, Hester went to a side table and began to rummage through its drawers. Lensborough took the opportunity to get the thing over with, crossing the room in half a dozen purposeful strides.

He cleared his throat. She jumped, as if truly startled to find him standing so close behind her. For some reason the gesture seemed like the height of impertinence. Women usually fell over themselves to attract his attention. How dare she be impervious to him, when he was gratingly aware of her every move?

‘Do you mean to stand there glowering at me all night, or is there something specific you wished to say?’

Hester’s head was still bowed over the packs of cards she was laying out on the table top.

A smile tugged at the corner of his lip. She might keep her head averted, but she was as aware of him as he was of her.

‘Vixen,’ he murmured, reassured. ‘You just cannot help yourself, can you? I suppose it is on account of your red hair.’

It was not a true red, though. Standing this close, in flickering candlelight, he could see strands amidst the copper that were almost black. The effect was of flames flickering over hot coals. The fire was spreading to her cheeks, too, a tide of heat sweeping down her neck. She turned suddenly, glaring directly up into his face.

‘I…you…’ she stammered, her fists clenching and unclenching in pure frustration. Hadn’t he already done enough? Sworn at her, abandoned her in her sopping clothes at the side of the roadside, and lastly provoking her to retaliating, in the most unladylike manner, to his jibe at the dining table, causing the shocked eyes of her entire family to turn in her direction. It hadn’t helped that Phoebe had promptly dissolved in a fit of the giggles, drawing a scathing glance for her own lack of self-control.

‘We must talk, you and I,’ he purred. ‘This matter between us needs to be addressed.’

They had nothing to talk about. Every time they got anywhere near each other disaster struck. She could not see that changing when everything about him infuriated her. The only way to avoid further clashes was to stay as far from him as possible.

She took a hasty step backward, preparing to dodge away. ‘I would far rather we simply not speak of it again.’

‘I can well believe that,’ he drawled. ‘However, I, at least, feel the need to explain my lapse of good manners.’

She gasped. How dare he imply her manners needed explaining? Even if they did, it was certainly not his place to say so.

She stepped smartly to one side, intending to get right away from him. He mirrored her movement so that they remained in the same relative position. He was determined that she should understand the cause of the language he had subjected her ears to, at least.

‘The way you were dressed, the fact you were on a public highway unescorted, led me to believe you were—’

‘A woman of no account,’ she flashed, her eyes blazing. ‘Yes, I had already come to that conclusion for myself.’ She drew herself up to her full height. ‘I suppose you are one of those imbeciles who think that if a lady of good birth goes visiting the poor she should do so in a carriage, attended by footmen, flaunting her wealth in the face of their poverty and making everyone ten times more wretched in the process.’