Полная версия

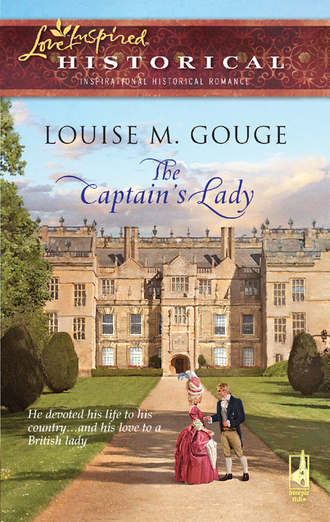

The Captain's Lady

After she and Mama left Papa and Jamie, it had been all she could do to keep from pleading for her mother’s support for that love, especially since Mama seemed reconciled to Frederick’s marriage. But Mama had excused herself to attend to household matters, leaving Marianne to languish outside Papa’s study in hopes of seeing Jamie again. That is, until her brother’s missive began to burn in her hand. Here was her ally in the family. Frederick would support her love for Jamie, of that she was certain.

Seated now in her bedchamber in her favorite place to read, Marianne broke the seal on Frederick’s letter and unfolded the vellum page. A small, folded piece fell out, so she quickly perused the first one, which repeated the information he’d written to Papa. The details about his dear wife assured Marianne that she would love Rachel and call her “sister” the moment they met.

Wishing that meeting might happen soon, she opened the smaller page—and gasped at the first words. “You must not think to do as I have done, dear sister. For reasons I cannot now explain, other than to say it is for your own happiness and written because I am devoted to you, you must release our mutual friend from the premature vows you traded with him on his last visit to London. To continue this ill-advised alliance will bring only heartache to you both. While he is a man of blameless character, he will not make a suitable husband for the daughter of a peer of the realm. I cannot say more except that you must, you must heed my advice, my beloved sister.”

Scalding tears raced down Marianne’s cheeks. Never had she expected such a betrayal from Frederick. Had they not been the closest of friends all their lives? Had she not frequently stood beside him against their three older brothers, the sons of Papa’s first wife, when they sought to bully him? Why did he not wish for her the same happiness he had claimed for himself?

Trembling with anger and disappointment, she resisted the urge to crumple the entire letter. Frederick had signed the first page as if it were the only one, no doubt knowing she would share its contents with Mama. But she reread the second one just to be certain she had not mistaken his cruel intentions. No, she had not. So Marianne ripped the page to shreds and fed the pieces to the hearth flames, then watched as the fire’s ravenous tongues eagerly devoured them.

Childhood memories of Frederick’s devotion sprang to mind. His comfort when she fell and scraped her chin. Their forays into Papa’s chambers to spy on guests. His gentle teasing, edged with pride, when she emerged from the schoolroom and entered society. Why would he abandon her now? She knelt beside her cold bed and offered up a tearful prayer that she might understand why God would let her fall in love with Jamie and then deny them their happiness.

The response came as surely as if the Lord had spoken to her aloud. Be at peace. This is the man you will marry.

“Lord, if this is Your voice, then guide my every step.”

Joy flooded her heart—and kept her awake into the early morning hours, planning how she would bring God’s will to pass.

Following an afternoon visit to an elderly pensioner who had served the Moberly family for many years, Marianne sat at supper wondering at the different opinions people held about Papa. The old servant had extolled Papa’s generosity and kindness, calling him a saint. Yet across the table from Marianne, Robert practically reclined in his chair, his usual protest against Papa’s nightly berating. Beside him sat Jamie, in the place where the ranking son should sit, his admiration of Papa obvious in his genial nods and agreeable words to everything Papa said. Doubtless Jamie had no idea that Robert should be sitting to Papa’s left. Of course Mama, as always, gazed down the length of the table at Papa with the purest devotion, a sentiment Marianne felt as deeply as a daughter could while still seeing his flaws.

Tonight the topic was the Americans and their foolish rebellion against His Majesty. Some anonymous colonist had written a pamphlet entitled “Common Sense,” which was causing considerable stir in London, and Papa seemed unable to contain his outrage.

“Common nonsense,” he huffed as he stabbed a forkful of fish and devoured it. “What do these colonists understand about the responsibilities of government?”

While he fussed between bites about His Majesty’s God-given duties to rule, and the Americans as recalcitrant children, Marianne glanced directly across the table at Jamie, whose thoughtful frown conveyed his sympathies for Papa’s remarks. Eager to turn the conversation to more pleasant topics, Marianne patted her father’s arm.

“But, dearest, if these colonies are so much trouble, why does His Majesty not simply break with them?”

From the corner of her eye, Marianne could see Jamie’s own eyes widen for an instant, but she turned her full attention to Papa. He returned a touch to her arm, along with a paternal smile.

“Ah, my dear, such innocence. You had best leave governing to the Crown and Parliament.”

Any other time, this response might have soothed Marianne. But for some odd reason, irritation scratched at her mind. She was not a child who should have no opinions, nor should she fail to seek information to enlighten her judgments. She knew of some ladies who expressed their political opinions without censure, including Mama’s acquaintance, the duchess of Devonshire.

“I agree with Marianne.” Robert’s voice lacked its usual indolence, a sign that he had not yet succumbed to his wine. “Let the colonies fend for themselves for a while without the Crown’s protection. Then when they’re attacked and plundered by every greedy country on the Continent, they’ll come crawling back under His Majesty’s rule.”

Marianne sensed the bitterness in his wily wording. His break with Papa had lasted less than three weeks before he came “crawling back.”

Papa regarded Robert for an instant, then dismissed his words with a snort and a wave of his hand. “Templeton, what do you think of this rebellion?”

While her heart ached for her brother, Marianne could now study Jamie’s well-formed face without fear of who might notice her staring at him. A sun-kissed curl had escaped from his queue and draped near his high, well-tanned left cheekbone. His straight nose bore a pale, jagged scar down one side that added character rather than disfigurement. She wondered what adventure had marked him thus, and would ask him at the first opportunity.

“I find it a great annoyance, milord.” Jamie’s brown eyes burned with indignation. “East Florida is prospering and should soon prove to be the most profitable of England’s American colonies. But shipping goods back and forth from London has become difficult since King George declared the wayward thirteen colonies to be in open rebellion. I cannot sail five hundred leagues without one of His Majesty’s men-of-war stopping me to be sure I have no contraband.”

“Hmm.” Papa leaned back in his chair and rubbed his chin. “Have my flag and my letter of passage been helpful?”

“Yes, sir. They have saved me more times than I can count. But every time I am forced to heave to—no less than four times on this last voyage—especially when I’m ordered to change my course for whatever reason the captain might have, it delays shipments. This isn’t a problem when I carry nonperishable goods. But our orange and lemon cargos can spoil if not delivered in a timely fashion.” Jamie bent his head toward the fragrant bowl of fruit gracing the table. “We barely managed to reach London with these still edible.”

As he spoke, Papa’s smile broadened. “That’s what I like about you, Templeton. No interest in politics. Just business. If those thirteen guilty colonies were of the same mind, there would be no rebellion.”

Marianne enjoyed the modest smile Jamie returned to Papa, but Jamie did not look at her. While the two men continued to talk, she cast about for some way to gain his attention. When the perfect scheme came to mind, she knew the Lord was continuing to lead her.

“Papa, may we discuss something other than business and the war?”

His wiry white eyebrows arched in surprise. “Forgive me, my dear. I believe your mother is of the same mind.” He bowed his head toward Mama, who had sent more than one disapproving frown his way during the meal. “What would you like to discuss?”

“Why, I wonder if you recall that Mama and I plan to visit St. Ann’s Orphan Asylum for Girls tomorrow.” She could not keep her gaze from straying to Jamie, who seemed to be particularly interested in the aromatic roast beef the footman had just set before him. “Would you like to make a small contribution to our efforts?”

“Of course, my dear. I shall see to it before I leave for Parliament tomorrow.” He cut into the meat before him, but paused with a bite halfway to his lips. “Why do you not take Templeton with you? I’m certain he would enjoy seeing more of London, and I would feel more at ease if you had the protection of his presence.”

Jamie coughed and grabbed his water goblet, swallowing with a gulp. Marianne did not know whether to laugh or offer sympathy. But as long as her plan worked…

“I say, Merry.” Robert sat up and leaned across his plate, his cravat nearly touching the sauce on his meat. “My tailor is coming tomorrow to fit Templeton’s new wardrobe. You know how petulant these Dutch tailors can be if one misses an appointment, which, I might add, I had a deuce of a time arranging so quickly. Can you not take Blevins or a footman or someone else on your little excursion?”

“It is not an excursion, brother dear. It is ministry.” Marianne knew she must continue talking before Papa began to berate Robert, for she could hear Papa’s warning growl that always preceded such scolding. “In fact, I do believe you would enjoy it, too. Why not join us? I am certain Mama will not mind waiting until Captain Templeton has been measured. All of us could go.” For the life of her—and even to save Robert’s dignity—she could not think of another thing to say.

“Just the thing, Moberly.” Jamie appeared to be taking up the cause, and Marianne’s heart lilted over his kindness. “Let’s accompany the ladies. I still don’t have my land legs, so the walking’ll do me good.”

Robert’s eyes shifted in confusion, and he blinked several times before his gaze steadied. “Rather, my good man. A splendid plan.” His grin convinced Marianne he knew they had saved him. But now mischief played across his face in a lopsided smirk. “Shall we not ride, then? You did agree to riding, you know.”

Marianne saw the dread in Jamie’s faint grimace. One day she herself would see to his riding lessons, for her brother would be merciless in the task. “But, Robert,” she said, “you know Mama and I must take our carriage, for we have many items to carry.”

“No doubt too many items to leave room for Templeton and me.” Robert nudged Jamie. “Do you not agree?”

Jamie’s jaw clenched briefly. “I thank you, Lady Marianne, but tomorrow is none too soon to begin my acquaintance with a saddle.”

She could not stop a soft gasp. Would he deliberately avoid her? Somehow she managed a careless smile. “Of course, Captain Templeton. Whatever you prefer.”

The footman behind her removed her half-eaten meat course and replaced it with a bowl of fruit. Marianne glanced at Papa, who was absorbed in his own bowl. Once again she had deflected his anger and thus defended one of her brothers.

But who would work in her defense? Who would see that her dreams were accomplished? Despite the verse in her morning reading, “Be still and know that I am God,” her heart and her faith dipped low with disappointment.

Jamie had thought his heart was settled in the matter of Lady Marianne, especially after his first session with Reverend Bentley, who’d expounded on the nature of British social structures and everyone’s place in it. As he’d left the good curate, Jamie had felt certain he’d conquered his emotions. But this supper turned everything upside down. The impossible choice set before him demanded an instant decision, and he could see how his words had wounded her. Ah, to be able to comfort her. Yet there could be no compromise, even though by choosing Moberly’s invitation, he was now forced to risk his neck to keep his distance from her. Jamie could not bear the closeness that a carriage would afford, even with her mother present.

He’d never had cause to trust or not trust Moberly. But youthful experiences had taught him that privileged gentlemen found great amusement in putting other men through the worst possible trials to test their mettle. In truth, he’d suffered the same treatment as a cabin boy, and inflicted the same on youths under his command. How else did one become a man?

But did his latest trial have to be on horseback?

Chapter Five

Jamie had always dressed himself, and Quince employed his own manservant, who had remained on his farm in Massachusetts. So it was a challenge for both men to go through the motions of acting as master and valet. But they each put on their best performance for Jamie’s fitting with Moberly’s tailor.

Soon, however, the tall, finicky man irritated Jamie to the extreme as he roughly measured him, tossed about colorful fabrics and barked orders at his harassed assistant, a dark-skinned boy of no more than thirteen. Other than his helper, the man spoke only to Moberly and only in his native tongue—French—clearly regarding Jamie as less than worthy of being addressed. Just as clearly, the tailor had no idea Jamie was fluent in his language and was having difficulty not responding to his insults.

When he turned at the wrong moment, the slender thread of a man lifted his hand as if to cuff him, but Jamie warned him off with a dark scowl.

“I thought you said he’s Dutch,” he said to Moberly through clenched teeth.

Sprawled out on the chaise longue in Jamie’s suite, Moberly gave the remark a dismissive wave. “If Bennington knew I used a French tailor, the old boy would have apoplexy. All that unpleasantness with the Frogs, you know.”

At his words, Jamie’s crossness softened. Moberly had a deep need in his life, yet how could Jamie speak to him of God’s grace while spying on his father? He lifted a silent prayer that somehow Lady Marianne might deliver the message of God’s love her brother needed to hear.

Jamie ducked to avoid the long pin the tailor wielded like a rapier to emphasize his ranting. Used to homespun woolen and linen, Jamie chafed at the idea of wearing silk, satin and lace, but he’d decided to tolerate Moberly’s choice of fabrics and styles. That is, until the tailor unrolled some oddly colored satin and draped it across Jamie’s shoulder. What a ghastly green, like the color of the sea before a lightning storm. He would not wear it, no matter what anyone said.

As if reading his mind, Moberly rested a finger along his jawline in a thoughtful pose. “No, no, not that, François. It reminds me of a dead toad. Use the periwinkle. It will drive the ladies mad.”

“Mais non, Monsieur Moberly.” François sniffed. “That glorious couleur I save for you, not this…this rustique.” He snapped his fingers to punctuate the insult.

“That’s it.” Jamie snatched off the fabric and flung it away, ignoring the derisive snort from Quince, who observed the whole thing from across the room. “My own clothes will do.”

Moberly exhaled a long sigh. “Now, François, look what you’ve done. I shall have to find another tailor.”

The middle-aged tailor gasped. “But, Monsieur—”

“No, no.” Moberly stood and walked toward the door. “I shall not have you insult Lord Bennington’s business partner and my good friend.”

The man paled. “Lord Bennington’s business partner?” Now his face flushed with color. “But, Monsieur Moberly, why did you not say so?” He turned to Jamie, his eyes ablaze with an odd fervor. “Ah, Monsieur, eh, Capitaine Templeton, for such a well-favored gentleman, oui, we must have the periwinkle.” He snapped his fingers at his assistant. “L’apportes à moi, tout de suite.”

The boy brought forth the muted blue fabric, a dandy’s color if ever Jamie saw one. When François draped it over his shoulder, Quince moved up beside Jamie and stared into the long mirror with him.

“Aye, sir, that’ll grab the ladies’ attention, no mistake.” The smirk on his face almost earned him Jamie’s fist.

“Bad news about your ship, Templeton.” Moberly’s comment surprised Jamie. “What’s all this about repairs?” Perhaps he’d noticed Jamie’s difficulty in restraining himself throughout this ordeal. Indeed, Jamie knew the report about the Fair Winds had set him back, for it meant he and Quince would be in London for an unknown length of time instead of just a month.

“The hull requires scraping and recaulking.” Jamie stuck out his arm so François could fit a sleeve pattern. “And the storm damage to the mast was worse than I thought. ’Twill take some time to fix it all.”

“Ah, well.” Moberly’s grin held a bit of mischief. “Once we finish the charity bits with Marianne and Lady Bennington, we’ll find ways to fill your time.”

In the mirror, Jamie traded a look with Quince. When his first mate, Saunders, arrived early that morning with disappointing news about the sloop, Quince reminded him of their prayers for this mission. God wasn’t hiding when the Fair Winds received storm damage, and He’d brought them safely to port. The Almighty still had this venture safely in His hands. All the more time to secure important information, Jamie and Quince agreed, but too much time for Jamie to be in Lady Marianne’s beguiling presence.

Once the torturous fitting session ended, the now-fawning tailor withdrew, and Jamie gripped his emotions for the coming events. After their midday repast, he and Moberly joined Lady Bennington and Lady Marianne for their visit to the orphan asylum. Yet, other than the brief quickening of his pulse at seeing Lady Marianne—dressed modestly in brown, as was her mother—he had only to deal with riding.

To his surprise, Moberly chose for him a large but gentle mare that followed Lady Bennington’s landau like an obedient pup. Jamie began to feel comfortable in the saddle. Moberly also furnished him with a pistol and sword to keep at hand lest unsavory elements be roaming the streets.

The trip across town, however, passed with unexpected ease and some pleasant sightseeing under a bright spring sky. Although the cool March breeze carried the rancid odors of the city waste and horseflesh, making Jamie long for a fresh ocean wind, he did notice some of London’s finer points. Upon catching a glimpse of the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral, he decided he must visit its fabled interior. Then some shops along the way caught his eye as possible sources of gifts for loved ones back home or, at the least, ideas for items to export to East Florida.

The carriage and riders entered the wide front courtyard of the asylum as though passing through a palace’s gates…or a prison’s. The wrought-iron fence’s seven-foot pickets were set no more than four inches apart, giving the three-story gray brick building a foreboding appearance, a sad place for children to grow up, in Jamie’s way of thinking. Not a scrap of trash littered the grassy yard, which still wore its winter brown, and not a single pebble lay on the paved front walkway. No doubt the denizens of St. Ann’s had swept the path with care for the expected visitors. Dismounting with only a little trouble, he saw with gratitude a stone mounting block near the building’s entrance. He would have no trouble remounting. Perhaps this horse riding would not be so bad, after all.

Robert assisted his stepmother’s descent from the carriage and looped his arm in hers. Jamie had no choice but to offer the same assistance to Lady Marianne. Taking his arm, she gave him a warm smile that tightened when her mother glanced over her shoulder. But the lady’s attention was on John the footman, who balanced several large boxes in his arms as he followed them. She gave the man a nod and turned back toward the door. Lady Marianne squeezed Jamie’s arm, and a pleasant shiver shot up to his neck. He tried to shake it off, to no avail. Wafting up from her hair came the faint scent of roses, compounding his battle to distance his feelings from her.

“Mama takes such delight in these visits,” Lady Marianne whispered as she leaned against his arm. “She loves the children dearly.”

He permitted himself to gaze at her for an instant, and his heart paid for it with a painful tug. “It seems you do, too, my lady.” Indeed, her eyes shone with an affection far different from the loving glances she’d sent his way. How he longed to learn of all her charitable interests. But that could not be.

“Oh, yes.” Her strong tone affirmed her conviction. “They do such fine work here, rearing these girls and teaching them useful skills. My own Emma came from this school.”

“Ah, I see.” Jamie was glad they reached the massive double front doors before he was required to comment further. He had yet to discover just how deeply Quince cared for Lady Marianne’s little maid, but he knew his friend would not play her false. Still, both men would likely end up sailing home with broken hearts.

As the group moved through the doors and into the large entrance hall, which smelled freshly scrubbed with lye soap, the soft thunder of running feet met them. Some hundred and fifty girls of all sizes hastened to assemble into lines, the taller ones in the back ranks, with descending heights down to the twenty or so tiny moppets in front. Each girl wore a gray serge uniform and a plain white pinafore bearing a number.

Jamie swallowed away a wave of sentiment. An orphan himself, he, too, might have been a nameless child raised with a number on his chest, had his uncle not taken him in.

A middle-aged matron in a matching uniform inspected the lines, her plain thin face betraying no emotion as she turned and offered a deep curtsy to their guests. As one, the girls followed suit.

“Welcome, Lady Bennington, Lady Marianne.” Another matron, gray-haired and in a black dress, stepped forward. Authority emanated from her such as Jamie had witnessed in the sternest of sea captains, but he also noted a hint of warmth as she addressed the countess.

“Mrs. Martin.” Lady Bennington’s countenance glowed as she grasped the woman’s hands. “How good to see you.” Her gaze swept over the assembly. “Good afternoon, my dear, dear girls.”

Mrs. Martin lifted one hand to direct the children in a chorus of “Good afternoon, Lady Bennington, Lady Marianne.” One and all, their faces beamed with affection for their patronesses.

While the countess made some remarks, Jamie noticed Lady Marianne leaning toward the little ones as if she wished to go to them. The countess then gestured to John the footman, who brought forth one of the boxes. Jamie followed Moberly’s lead and moved back against the wall while the two ladies disbursed knitted mittens, scarves and caps they and their friends had made. The children’s joy and gratitude punctured Jamie’s self-containment, and he tried to grip his emotions. Still, breathing became more difficult as the scene progressed.

When Lady Marianne knelt on the well-scrubbed wooden floor among the smallest orphans, gathering in her arms a wee brown-haired tot to show her how to don her mittens, Jamie’s last defenses fell away, and a shattering ache filled his chest.

Lord, forgive me. I love this good lady beyond all sense, beyond all wisdom. Only through Your guidance can I walk away from her. Yet if, in Your great goodness, You could grant us happiness—

Jamie could not permit himself to complete the prayer. He would neither request nor expect the only answer that would give him personal joy. Not when there was a revolution to be fought and a fourteenth colony to draw into the mighty fray. If he must lose at love, so be it.

But he must not lose at war, for in that there was so much more at stake—nothing less than the destiny of a newborn nation.

Chapter Six

“Captain Templeton looks quite presentable in his new riding clothes, do you not think, Grace?” Marianne sat in the open carriage beside Mama’s companion, whom she had borrowed for today’s outing to Hyde Park. “Robert approves, or he would not have agreed to bring the American with us.” She herself had been stunned when Jamie walked into the drawing room just an hour ago, for the cut of his brown wool coat over his broad shoulders and the close lines of his tan breeches over his strong legs emphasized his superior masculine form. Why, if not for his colonial speech, he could pass for a peer of the realm.