Полная версия

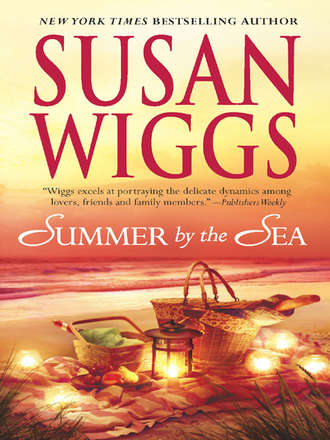

Summer By The Sea

The cool water brought relief as she submerged herself. The places she’d been stung were instantly soothed by the silky mud on the bottom. She broke the surface and saw a few bees still hovering around, so she sat in the shallow water, waving her arms and legs, stirring up brown clouds. She didn’t know how long she sat there, letting the mud cool the stings. She could detect six of them, maybe more, mostly on her legs.

“What in heaven’s holy name is going on?” demanded a sharp voice. A woman rushed out of the house and down the back stairs.

Rosa almost didn’t recognize Mrs. Carmichael in her starched housekeeper’s uniform. The Carmichaels lived down the street from the Capolettis, and usually Rosa only saw her in her housedress and slippers, standing on the porch and calling her boys in to dinner. Everything was different in this neighborhood of big houses overlooking the sea. Everything was cleaner and neater, even the people.

Except Rosa herself. As she slogged to the edge of the pond, feeling the smooth mud squish between her toes, she knew with every cell in her body that she didn’t belong here. Muddy and barefoot, soaked to the skin, bee-stung and bruised, she belonged anywhere but here.

She waited, dripping on the lawn as Mrs. Carmichael bustled toward her. “I can explain—”

“What are we going to do with you, Rosa Capoletti?” Mrs. Carmichael demanded. She was on the verge of being mad, but she was holding her temper back. Rosa could tell. People tried to be extra patient with her, on account of her mother had died on Valentine’s Day. Even Sister Baptista tried to be a little nicer.

“I can get cleaned off in the garden hose,” Rosa suggested.

“Good idea. I hope you didn’t do in any of the koi.”

“The what?”

“The fish.”

“I didn’t mean to.”

Mrs. Carmichael shook her head. “Let’s go.”

As she followed Mrs. Carmichael across the lawn, Rosa glanced at the house and saw a ghost in the window. A small, pale person with a round Charlie Brown head stood staring out at her, veiled by lace curtains. She looked again and saw that the ghost was gone, shy as a hummingbird zipping out of sight.

“Holy moly,” she muttered.

“What’s that?” Mrs. Carmichael cranked opened the spigot.

“Oh, nothing.” It was kind of interesting, seeing a ghost. Sometimes she saw Mamma, but she didn’t tell anyone. People would think she was lying, but she wasn’t.

“Stand right there.” Mrs. Carmichael indicated a sunny spot. The grass was as soft as brand-new shag carpet. “Hold out your arms.”

Rosa’s shadow fell over the grass, a skinny cruciform with stringy hair. An arc of fresh water from the hose drenched her. “Yikes, that’s cold,” she said.

“Hold still and I’ll be quick.”

She couldn’t hold still. The water was too cold, which felt good on the beestings but chilled the rest of her. She jumped up and down as though stomping grapes, like Pop said they used to do in the Old Country.

The ghost came to the window again.

“Who is that?” Rosa asked through chattering teeth.

“He’s Mrs. Montgomery’s boy.”

“Is he all alone in there?”

“He is. Put your head back,” Mrs. Carmichael instructed. “His sister went away to summer camp.”

“I bet he’s lonely. Maybe I could play with him.”

Mrs. Carmichael gave a dry laugh. “I don’t think so, dear.”

“Is he shy?” Rosa persisted.

“No. He’s a Montgomery. Now, turn around and I’ll finish up.”

Rosa squirmed under the impact of the cold stream of water. When the torture stopped, Mrs. Carmichael told her to wait on the back porch. She disappeared into the house, carefully closing the door behind her. She returned with a stack of towels and a white terry-cloth bathrobe. “Put this on, and I’ll throw your clothes in the dryer.”

As Rosa peeled off her wet clothes, Mrs. Carmichael stared at her legs. “Mother of God, what happened to you?”

Rosa surveyed the welts on her feet and legs. “Bee-stings,” she said. “I kicked a hive. It was an accident, I swear—”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

Rosa thought it would be rude to point out that she had already tried to explain.

“Heavenly days,” said Mrs. Carmichael, wrapping a towel around her. “You must be made of steel, child. Doesn’t it hurt like hellfire?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“It’s all right to cry, you know.”

“Yes, ma’am, but it won’t make me feel any better. The mud helped, though. And the cold water.”

“Let me find the tweezers and get those stingers out. We might need to call a doctor.”

“No. I mean, no, thank you.” Rosa hoped she sounded firm, not impolite. While Mamma was sick, the whole family had had their fill of doctors. “I don’t need a doctor.”

“You sit tight, then. I’ll get the tweezers.”

A few minutes later, she returned with a blue-and-white first-aid kit and used the tweezers to pluck out at least seven stingers. “Hmm,” Mrs. Carmichael mused, “maybe it wasn’t such a bad idea, jumping in the pond. I think it’ll keep the swelling down.” She gently pressed the palm of her hand to Rosa’s forehead, and then to her cheek.

Rosa closed her eyes. She had forgotten how good it felt when someone checked you for fever. It had to be done by a woman. A mother had a way of touching you just so. It was one of the zillion things she missed about Mamma.

“No fever,” Mrs. Carmichael declared. “You’re lucky. You’re not allergic to beestings.”

“I’m not allergic to anything.”

Mrs. Carmichael treated the stings with baking soda and gave Rosa a grape Popsicle. “You’re very brave,” she said.

“Thank you.” Rosa didn’t feel brave. The beestings hurt plenty, like little licks of fire all over, but after what happened with Mamma, Rosa had a different idea about what was worth crying about.

Mrs. Carmichael got a comb and tugged it through Rosa’s long, thick, curly hair. Rosa endured it in silence, biting her lip to keep from crying out. “This is a mass of tangles,” Mrs. Carmichael said. “Honestly, doesn’t your father—”

“I do it myself,” Rosa said, forcing bright pride into her tone. “Pop doesn’t know how to do hair.”

“I see.”

Rosa pressed her lips together hard and stared at the painted planks on the porch floor. “Mamma taught me how to make a braid. When she was sick, she used to let me get in bed with her, and she’d do my hair.” Rosa didn’t tell Mrs. Carmichael that by the end, Mamma was too weak to do anything; she couldn’t even hold a brush. She didn’t tell her that the sickness that had taken Mamma took some of Rosa, too, the part that was easy laughter and feeling safe in the dark at night, the security of living in a house that smelled of baking bread and simmering sauce.

“Dear? Are you all right?”

Rosa tucked the memories away. “Mamma said every girl should know how to make a braid. But it’s hard to do on your own head.”

Mrs. Carmichael surprised her by holding her close, stroking her damp head. “I guess it is hard, kiddo.”

“I’ll keep practicing.”

“You do that.” Like all grown-up women, Mrs. Carmichael was a champ at braiding hair. She made a fat, perfect braid down Rosa’s back. “I’ll put these things in the dryer. Wait here, and try to stay out of mischief.”

Six

The housekeeper disappeared again and Rosa tried to be patient. Waiting was the pits. It was totally boring, and you never knew when it would end. She fiddled with the long tie that cinched in the waist of the thick terry robe. It was way too big for her, the sleeves and hem practically dragging.

Somewhere far away, the phone rang three times. Mrs. Carmichael’s voice drifted through the house. Rosa couldn’t hear the conversation, but Mrs. Carmichael laughed and talked on and on. She probably forgot all about Rosa.

The door to the kitchen was slightly ajar. Rosa pushed it with her foot and, almost all by itself, it swung open. She gasped softly at what she saw. Everything was white and steel, polished until it shone. There were miles of countertops, and Rosa figured the Montgomerys owned every tool and utensil that had ever been invented—strainers and oddly shaped spoons, gleaming pots hanging from a rack, a huge collection of knives, baking pans in several shapes, timers and stacks of snow-white tea towels.

Boy, thought Rosa, Mamma would love this. She was the world’s best cook. Every night, she used to sing “Funiculi” while she fixed supper—puttanesca sauce, homemade bread, pasta she made every Wednesday. Rosa had loved nothing better than working side by side with her in the bright scrubbed kitchen in the house on Prospect Street, turning out fresh pasta, baking a calzone on a winter afternoon, adding a pinch of basil or fennel to the sauce. Most of all, Rosa could picture, like an indelible snapshot in her mind, Mamma standing at the sink and looking out the window, a soft, slightly mysterious smile on her face. Her “Mona Lisa smile,” Pop used to call it. Rosa didn’t know about that. She had seen a postcard of the Mona Lisa and thought Mamma was way prettier.

Rosa walked through the strange high-ceilinged kitchen, running her finger along the edge of the counter. She stood on tiptoe to peer out the window over the sink. It framed a view of the sea. Her mother would’ve gone nuts for this kitchen.

But it didn’t smell like anything, just faintly of cleanser. Mamma’s kitchen always smelled like roasting chicken or baking pizza or freshly squeezed lemons.

Rosa finished her Popsicle and put the stick in a shiny, bullet-shaped trash can. She tried to keep still, she really did, but curiosity poked at her. She knew it was wrong, but she was going to snoop. She had always wondered about these great big houses. She’d seen them from the outside, painted giants with white scrollwork trim, shiny cars in the circular drives and yards where people in summer hats and starched white shirts held garden parties.

She walked down a hallway, her bare feet soundless on the polished wood floor, the hem of the robe dragging. Her hand stole inside the bathrobe to clutch at the shiny new key Pop had given her. She was old enough to have a house key now, and he told her never to lose it.

She could hear snatches of Mrs. Carmichael’s phone conversation, and when she realized it was about her, she froze right under a big painting of a sailboat in a rustic frame.

“…know what to do with that poor little girl all summer. Pete wasn’t gone five minutes and she got in trouble.”

Pete was Pop. It seemed like every woman who knew him was waiting for him to mess up now that he didn’t have a wife anymore.

“Oh…no idea,” Mrs. Carmichael was saying. “The kindest thing he can do for that child is remarry. She needs a mother.”

No, thank you. Rosa buried her face in the overly long sleeves of the bathrobe to stifle a snort. She absolutely did not need a mother. She had the best mother in the world, and just because she wasn’t around anymore didn’t mean she was gone. She belonged to Rosa in a special way. That’s what Father Dominic said, and everyone knew priests didn’t lie.

I still talk to you, don’t I, Mamma? She thought the words as hard as she could.

“At least Pete’s got his work,” Mrs. Carmichael went on. “He’s happy when he works. He’s like a different person.” She gave a gentle laugh. “Hmm. I know. And with those looks of his…”

Rosa got bored with eavesdropping. Everyone was always saying how Pop was still young and good-looking, and that he ought to find another wife. Why did people think you could replace someone, like she was a lost schoolbook and all you had to do was bring a check to the office and they’d give you another?

She continued her silent exploration of the house, feeling as though she had stepped into an enchanted castle. The front room was all white and lemony-yellow, with white furniture and a seashell collection in a jar. Photographs in silver frames pictured people in white clothes without wrinkles, just like in a magazine ad. There was a huge bouquet of cut flowers, probably from the garden Pop took care of. The glass-topped coffee table displayed an important-looking scrimshaw collection. The mantel had a crystal candelabrum with long white tapers that had never been lit.

This wasn’t like going over to Linda’s house to play. Everything was so big and so incredibly quiet. The flowers made it smell like the funeral home where they took Rosa’s mother.

She backed out of the room and tiptoed down the hall. Tall double doors with glass panes framed a room that had more books than the Redwood Library in Newport.

Rosa loved books. When Mamma got too sick to do anything else, and couldn’t even braid hair anymore, Rosa used to get in bed with her and read and read and read—The Indian in the Cupboard, Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing, Charlotte’s Web and poems from A Light in the Attic. And of course, Goodnight Moon, which Mamma used to read to Rosa every night when she was tiny.

She stepped into the room and inhaled the musty sunshine smell of books. She walked over to the lace-paneled windows and discovered a view of the garden and pond. Rosa caught her breath. The ghostly boy had stood right there, at the window, watching her run from attacking bees.

She wanted to browse through the books on the shelves, but she became aware of a hissing-gurgling-sucking sound. A creepy chill slipped over her skin. This was a haunted library.

She spun away from the window and saw the ghost on the couch.

Rosa had to push both fists against her mouth to keep from screaming. He was doing a terrible thing, sucking steam from a snaky plastic tube into his mouth. The tube was attached to a box, which emitted the hissing sounds.

Finally she found her voice. “What are you doing?”

He pulled the tube away from his mouth. “This helps me breathe,” he said. “It’s a portable bronchodilator.”

She edged a little closer, but still felt wary. He was very skinny, lying on a leather sofa with a sailboat quilt covering him up. He wore wire-rimmed glasses and had a nice face, nicer than you’d expect for a ghost boy. Pale yellow hair, pale blue eyes, pale white skin.

“You need help breathing?” she asked.

“Sometimes.” He set aside the tube, hooking it into a holder on the side of the machine. A wisp of steam coughed from the mouthpiece. “I have asthma.”

“Can you get rid of it?” Rosa tensed up, wishing she hadn’t asked. Sometimes a person got sick and there was no way to get better.

“No one can tell,” he said. “It can be controlled, and maybe it’ll improve when I get bigger and my lungs grow. What’s your name?”

“Rosina Angelica Capoletti, and everyone calls me Rosa. What’s yours?”

“Alexander Montgomery.”

“Does everyone call you Alex?”

He offered a mild, sweet smile. “No one calls me that.”

“Then I think I will.”

They verified that they were just a year apart in age, but in the same grade. Alex had started kindergarten a year late on account of having trouble with his asthma. He admitted that he disliked school, and she got the impression that he got bullied a lot. She declared that she, too, despised school.

“I know I have to go,” she lamented. “It’s the only way to get ahead.”

“Ahead of what?” he asked.

She laughed. “I don’t know. My brothers were in ROTC and joined the U.S. Navy for their education.”

“You go to college to get an education,” he said with a frown.

“If you go in the navy first, then the navy pays for it,” she explained patiently. “I thought everybody knew that.” She indicated the book that lay open across his lap. “What are you reading?”

He picked it up and showed her the spine. “Bulfinch’s Mythology. It’s a collection of Greek myths. This one is about Icarus. There’s a picture.”

Rosa sat beside him on the sofa and scooted over to see. Alex thoughtfully put half the book on her lap. “He’s flying,” she said.

“Yes.”

“He doesn’t look like he’s having much fun.”

“Well, he’s in pain.”

“Why would he fly if it hurts him?”

“Because he’s flying,” Alex said as if that explained everything.

Rosa stuck out her bare foot. The beestings formed red dots on her ankle and shin. “I tried flying, and trust me, it’s not worth the pain.”

“I saw you,” he said. “I was watching from the window.”

“I know. I saw you watching me.”

“I was going to come and help, but I didn’t know what to do.”

“That’s all right. Mrs. Carmichael came straightaway when she heard me yelling.”

He nodded gravely, studying her with such total absorption that she felt like the only person on the planet. “Do the beestings hurt?”

“Not anymore. Mrs. Carmichael put baking soda on them. She said I’m lucky I’m not allergic.”

“You are lucky,” he said with a funny, dreamy look on his face. “You get to be outside and do whatever you want.”

She thought about telling him just how unlucky she was. She was a girl without a mother. But she didn’t want to say anything. Not just yet. It might be too scary for him, this sick boy, to hear about a sick person who had died.

“You mean you’re not allowed outside?”

He pushed his glasses up the bridge of his nose. “Not without supervision. I might have an asthma attack.”

“Going outside causes an attack?”

“Sometimes.”

She’d heard of a heart attack. An attack of nerves. But not an asthma attack. “What’s it feel like?”

“It’s like…drowning. But in air instead of water.”

Rosa had some knowledge of the sensation. More than once, while swimming, she’d gone out too far and under too deep, and she’d experienced the momentary panic of needing air. The feeling was horrifying. “Then you’d better not go outside.”

He stared down at Icarus, whose mouth was twisted in agony as he flew too close to the sun. Then he looked up at Rosa, and there was a new light in his blue eyes. “Let’s go anyway.”

“Really?”

“My lungs were twitchy this morning, but I’m better now. I’ll be okay.”

She looked at him very closely. There were no lies in that face of his. She could just tell. “I have to get my clothes. Mrs. Carmichael put them in the dryer.”

“I think that might be in the utility room.”

As she followed him through the house, she marveled that he didn’t know for sure where the dryer was. At her house, everyone knew, because laundry was everyone’s business. He opened a painted door in the kitchen to reveal a dim, cavernous room dusty with dryer lint. “It’s in there.”

“You wait here.”

“Are you sure?”

“I have to change. I sure don’t need any help doing that.” The room smelled of must and dryer lint, and a hissing sound came from the water heater. Her clothes were still damp, but she put them on anyway—undies, cutoffs and a T-shirt from Mario’s Flying Pizza. The sun would finish the job of drying them. She left the bathrobe on top of the dryer and hurried back to the kitchen.

There, she found Alex and Mrs. Carmichael locked in a staredown. “I’m going,” he said to the housekeeper.

She sniffed. “You’re not to leave the house.”

“That was this morning. I’m better now. I have my inhaler and my epi-pin, see?” He took a plastic thing in a yellow tube from the pocket of his shorts.

“I’ll watch him,” Rosa blurted out. “I will, Mrs. Carmichael. If he starts looking sick, I’ll make him come right back inside.”

The housekeeper kept her hands planted on her hips, though her eyes softened and there was a barely perceptible easing of her shoulders. Mothers were like that. They gave in with their eyes and their posture before saying okay out loud. “You will, will you?” she asked.

“Yes, ma’am. I got my things from the dryer. Thank you, Mrs. Carmichael.”

“You’re very welcome.” She looked from Alex to Rosa. “Try to keep your noses clean, all right?”

“Yes, Mrs. Carmichael,” they said together, trying not to look too gleeful.

Out in the sunlight, Rosa noticed that Alex’s eyes were ocean-blue, and they crinkled when he grinned at her. She vowed to be on her best behavior, just like Mrs. C had admonished them. If she got in trouble, Pop wouldn’t let her come to work with him anymore. He’d make her stay with that dreadful Mrs. Schmidt, the widow with the mustache, whom Rosa likened to a circling buzzard. Even before Mamma died, Mrs. Schmidt had started coming around the house, bringing covered dishes and making eyes at Pop, which of course he never even noticed.

“Here. Have a cookie.” As they headed for the door, Mrs. Carmichael held out a white jar in the shape of a sandcastle.

“Thank you.” They each took one and stepped out into the sunshine. Rosa nibbled on the cookie as she grinned at Alex.

It was a store-bought sugar cookie. Not as good as Mamma’s, of course. Mamma made hers with a secret ingredient—ricotta cheese—and thick, sweet icing. Now that was a cookie.

Ricotta Cheese Sugar Cookies

1 cup softened butter

2 cups sugar

1 carton full-fat ricotta cheese

2 eggs

3 teaspoons vanilla (the kind from Mexico is best)

½ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon grated lemon zest

4 cups flour

For the glaze:

1 cup powdered sugar

2-4 Tablespoons milk

2 drops almond extract (optional)

sprinkles

Preheat oven to 350° F. Mix cookie ingredients to form a sticky dough. Drop by teaspoonfuls on an ungreased cookie sheet. Bake 10 minutes or until the bottoms turn golden brown (the tops will stay white). Transfer to wire racks to cool. To make the glaze, stir milk a few drops at a time, along with the almond extract if desired, into the powdered sugar in a saucepan. Stir over low heat to create a glaze. Drizzle over cooled cookies and top with colored sprinkles. Makes 3-4 dozen cookies.

Seven

“Too bad about the rope swing,” Alex said, eyeing the rope that still hung from the tree branch.

“I took it from that shed behind the—what is that building, anyway? It’s too big to be a garage,” Rosa said, stopping to put on her flip-flops. The tall building was painted and trimmed to match the house. It had old-fashioned sliding wooden doors like a barn, an upper story at one end with a row of dormer windows facing the sea and a cupola with a wind vane on top.

“My mother parks her car there. She calls it the carriage house even though there’s no carriage in it.”

Sunlight glinted off the windows at the top of the house. “I knew it was way too fancy to be called a garage. Does somebody live there?”

“No, but somebody used to. In the olden days, a caretaker lived upstairs.”

“What did he take care of?”

“The horses. And carriages, I guess, but that was a long time ago. My grandfather used it as an observatory. He showed me how to spot the Copernicus Crater with a telescope.”

He sure did seem smart. Rosa nodded appreciatively, as though she knew what the Copernicus Crater was.

“My grandfather was teaching me about the stars, but he died when I was in first grade.”

Rosa didn’t quite know what to say about that, so she followed him across the property to the carriage house. The front doors were stuck, but they struggled together to push them along the rusted runners. Inside was a maze of spiderwebs, old tools and some sort of car under a fitted cover. “My mother’s car,” Alex said. “She calls it her beach car. It’s a Ford Galaxy. She hardly ever drives it, though.”

“My mother didn’t like driving, either.”

He shot her a quick look, and Rosa realized that now was her chance to tell him, because she’d said “didn’t” instead of “doesn’t.” But she decided not to say anything. Not yet. She might later, though. She’d already decided he was that kind of friend.

Before he could question her, she ran up the stairs. Sure enough, there was a whole house up there, flooded with dusty sunshine. Alex sneezed, and she turned to him. “Is this going to cause an as—” She couldn’t remember the word. “An attack?”