Полная версия

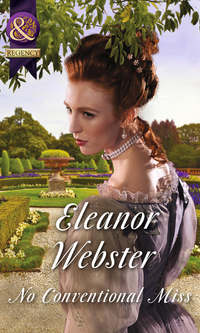

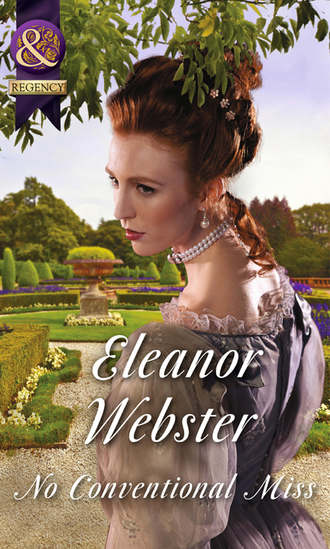

No Conventional Miss

Of course, it was that vision. It was the sight of that rain-spattered lake.

No, it was the man also—his dark good looks, that feeling of sadness which seemed a part of him and the way he made all else dwindle to unimportance.

Rilla picked up her mother’s rosebud cup. She ran her finger across its rim. The gilt had worn off and the china was so fragile as to be translucent.

It would have been better if Imogene had met him. She had poise and would not be scrabbling up trees—

Imogene!

Rilla gulped. She’d quite forgotten her younger sister. She put down the cup, hurrying to the staircase that led to the bedchambers upstairs.

‘Imogene! The viscount’s here!’

Imogene flung open her door with unaccustomed haste. The scent of rose water spilled from the room as she stepped on to the hall landing. ‘The viscount? Lord Wyburn? Here? What’s he like?’

‘Judgemental and unhappy.’

Imogene started, her blue eyes widening. ‘He said so?’

Rilla wished she hadn’t spoken. ‘No,’ she admitted after pause.

‘Then why do think he is unhappy?’

Rilla hesitated. She rubbed her hands unnecessarily across the fabric of her gown. ‘I—um—felt it.’

‘Felt? No.’ Imogene’s voice was high with strain. ‘It has been years almost.’

Eleven months.

‘It was nothing. I am making too much of it, honestly,’ Rilla said, hating to see her sister’s worry. ‘It was my imagination. And I’m quite well now.’

‘You’re still pale.’

‘From my fall, I’m sure.’

‘You fell? Are you hurt?’ Imogene’s voice rose again, threaded with anxiety as she noticed a pink scratch on Rilla’s forearm.

Rilla followed her gaze. ‘It’s nothing. Look, you go and charm him. Convince him that we are not hoydens while I make tea.’

‘And you’ll not dwell on—on feelings?’

‘I will concentrate entirely on the tea. You go. The gentlemen are in the study.’

‘You couldn’t lure Father out to the drawing room?’ Imogene asked as they started back down the stairs.

‘I didn’t even try.’

Halfway down, they heard the kitchen door open. Mrs Marriot must be back. The housekeeper always visited her sister every Thursday.

‘Good,’ Imogene said. ‘Let her make tea while you tidy yourself.’

Instinctively, Rilla touched her unmanageable hair. She’d never liked red hair. Witch hair. That is what the village children had called it.

She nodded, returning upstairs without comment. She cared nothing for beauty. The last thing she wanted was to attract a man.

But she must look sane. Above all else, she must look sane.

Chapter Two

Rilla entered the study anxiously, but everyone seemed congenial. Imogene sat ensconced in the window seat. Their father had pulled his chair from behind the desk and was discussing the antiquities. The viscount, who had risen at her entrance, was smiling and not, at present, asking anyone pointed questions about the cost of a London début.

‘Refreshments will be here shortly,’ she said, a little breathlessly.

Her father nodded. ‘Good, good. Make yourself comfy, m’dear. I was relating an anecdote from my most recent translation.’

He waved the papers in his hand and dust motes sparkled, dancing in a shaft of light.

The only vacant seat was on the sofa beside Lord Wyburn. Rilla hesitated. She caught his eye, but found his expression unreadable.

She swallowed and stared fixedly at the brocade upholstery. Her father waved the papers with an agitated motion. ‘Do sit, m’dear.’

Rilla sat. The viscount sat. The cushioning creaked. She had ample room and yet she felt conscious of his nearness—his muscled thighs, his fingers splayed across the worsted cloth of his trousers, even the heat of his body.

This was irrational. Several inches separated them. It was, therefore, scientifically impossible to detect warmth, except perhaps in the event of a raging fever.

Generally, scientific analysis comforted her mind. Today it proved useless.

Gracious, his legs were long. His feet stretched almost to the hearth. And muscular. Although she’d best forget his legs and attend to the conversation unless she wanted to seem a complete ninny.

They were discussing antiquities, naturally. Her father seldom participated in conversations on any other subject.

‘I travelled to Athens last year,’ Lord Wyburn said.

‘Aha!’ Sir George pulled his chair forward with a scrape of its legs. ‘And what, sir, is your opinion of Lord Elgin’s decision to remove the marbles from Greece and bring them to England, eh?’

‘It was wrong,’ the viscount answered easily.

‘But,’ Rilla blurted because she could not help it, ‘if he had not, the marbles would have been destroyed!’

The viscount shifted, turning towards her and, in so doing, narrowed the gap between them. ‘Indeed, Miss Gibson, but was it not a crime to take them from Greece? To do business with the Turks and bring them here?’

Their gazes met. Again, Rilla had a disconcerting feeling that all else in the room had shrunk, diminishing and fading to unimportance.

She had thought his eyes a dark, opaque brown and now realised they weren’t. Their colour was hazel, flecked with gold and green.

‘A lesser crime than to do nothing and allow their destruction,’ she said, with effort.

‘So it is right to preserve beauty from the past and undermine a country’s sovereignty in the present?’

‘I—’ She frowned because she had not thought of it like this and could see validity in his argument. ‘Yes, I think so. The marbles are our heritage. They are the heritage not only of one country, but of mankind. We hold them in trust for future generations. The politics of today are transient.’

‘I am not certain if the Greeks would agree. You are an individual with strong opinions.’

She flushed. ‘A trait not generally admired.’

‘I admire your honesty, but you may need to exercise discretion if you expect to do well in London society.’

‘Oh, I don’t,’ she said.

The straight eyebrows rose. ‘Then you are indeed unusual. To what do you aspire in London?’

‘Well, to see the London Museum, the Rosetta Stone and—’

Rilla left the sentence unfinished, catching Imogene’s look.

‘It appears you do not share the dreams common to most young ladies,’ Wyburn said.

‘Not for myself,’ she said, then stopped.

She had revealed more than she had intended.

Thankfully, Imogene interrupted the slight pause. ‘You said London, Lord Wyburn. Does that mean you will not oppose Lady Wyburn’s plan?’

‘It means, Miss Imogene, that your début will afford my stepmother amusement and I seldom deny her pleasure.’

‘We are much obliged.’

‘Quite so.’ The viscount turned his gaze to Rilla. ‘It would seem, Miss Gibson, that I will have the pleasure of hearing more about your singular opinions in London.’

* * *

Rilla, Imogene and Lady Wyburn had arrived at the capital within the fortnight. They spent the first week shopping, drinking tea and allowing a bossy French maid to style their hair into any number of styles.

Actually, Heloise appeared to be the only member of Lady Wyburn’s staff under the age of seventy. Her butler, Merryweather, was so bent and wizened that Rilla longed to take the tray and bid him sit. She didn’t, however, fearing to insult his dignity.

As for Wyburn, they did not see him at all as he had gone to his estate.

‘Which he hates,’ Lady Wyburn explained. ‘It always makes him dreadfully grumpy.’

The viscount’s absence filled Rilla with both relief and irrational disappointment.

‘He made me feel like I had a smudge on my face,’ she explained to Imogene. ‘I want to prove that I am not always like that, but have adequate social graces.’

‘Except you usually do have a smudge on your face. Although I suppose it is a step forward that you actually care about your smudges.’

Rilla stiffened. Imogene was right. She usually didn’t care. She frowned. She was sitting on Imogene’s bedroom floor beside her churn and she ran her fingers along its smooth wood, twisting the waterwheel so that it moved with a clunk...clunk...

‘But,’ Imogene added with a nod towards this apparatus, ‘if you do now care about smudges, you’d best stay away from that contraption.’

‘It is a perfect reproduction of my churn made precisely to a quarter-scale. Besides you are quite right, I have never cared about dirt or oil before and I see no reason to start now.’

‘I didn’t mean—’

But Rilla was leaning over the churn as though in an embrace, absorbed in both altering the trough’s angle and moving the wheel with a continued rhythmic clunk.

* * *

Lord Wyburn had announced his return with an invitation to the British Museum.

‘Which is an odd choice for an excursion,’ Lady Wyburn stated after reading the missive. ‘Indeed, he is too fond of ancient things and is like to become as bad as your father.’

Despite these comments, Lady Wyburn quickly wrote back their acceptance and announced that the excursion would prove a pleasant change from drinking tea which was too often as weak as dishwater.

But even with warning of his return, Rilla found the sight of him standing within the entrance hall disconcerting. She jerked to an abrupt stop on the stairs, aware of a marked change in her equilibrium without any scientific cause, given that she was neither in a boat or on carriage.

Perhaps it was his size, seemingly huge as he stood within Lady Wyburn’s hall. Or maybe he reminded her too much of her father’s gambling ‘friends’.

Indeed, that must be it, Rilla decided, glad of this explanation.

Certainly, he looked every inch the Corinthian in a well-tailored jacket, beige pantaloons and polished Hessians.

Yet, as she studied him unseen, she was conscious of sadness. It was not, thank goodness, a feeling, but rather she was aware of a shadowed bleakness in his expression, a tightness in his jaw and the sense that unpleasant topics occupied his mind.

Moreover, she realised, with a second start of surprise, that she longed to change that. She wanted to see his expression lighten with wit and interest.

‘Ah, there you are. Lovely to see you, dear boy.’ Lady Wyburn bustled into the hall.

Wyburn turned and bowed. ‘And you, my lady.’

‘Although whatever made you think of the museum, I do not know. Not that I’m not delighted, of course, but I have never truly appreciated the fascination accorded to ancient things. I mean, a jug is a jug even if it is thousands of years old. Besides, we don’t even know if it was part of someone’s second-best set. I would hate my second-best crockery to be on display.’

‘That is a novel perspective. I suggested the museum because I recalled that Miss Gibson had expressed an interest. Indeed, here she is now.’

He smiled as Rilla descended the stairs. He had a dimple, just one, set within his left cheek. Rilla hadn’t noticed it previously. Briefly that dimple fascinated. Again, she had an off-kilter, slightly breathless feeling as though climbing too high or galloping fast.

‘I could have waited.’ Her stomach also felt odd. Perhaps she had eaten insufficient breakfast.

‘But it is lovely for you to think of my sister’s interests. We are both much obliged,’ Imogene added, also descending the stairs.

They now stood in the hall. Wyburn seemed taller than ever. Rilla felt an irrational irritation both with his height and the crush. She wondered if perhaps London houses had dimensions smaller than that of their country counterparts and whether this might be suitable for scientific study.

* * *

The carriage ride through Bloomsbury fascinated Rilla. Thoughts of the museum crowded her mind, but she soon found the journey interesting on its own account. She loved the busy, bustling streets filled with vendors, newsboys, pedestrians and even stray dogs hunting for scraps. She loved also the interesting mix of carriages, high-sprung phaetons, carts and tradesmen’s vehicles.

She actually found it far pleasanter to focus on the activities outside the carriage than its interior. She knew she did not have a shy bone in her body, but somehow Lord Wyburn’s proximity or the carriage’s stuffy closeness had scattered her thoughts like so much dandelion fluff.

Indeed, only by pressing her face to the window and analysing the differing designs of carriage wheels could she keep her usual composure.

When they drew to a stop at the museum, Rilla felt a moment of disappointment. The external façade looked so ordinary. It was a solid building with a slate roof and two wings jutting out for stables.

But what did she expect, statues lining the drive?

It was the inside that mattered and which had inhabited her dreams for so long. Her earliest memories were filled with stories of Greeks, Romans and Egyptians. They were her bedtime stories, her fairy tales...

After descending from the coach, the party entered the building and a short, bent gentleman ambled forward to greet the visitors. He spoke in guttural tones and nodded towards a staircase leading to the first floor.

‘We have exhibits up there as well as in our newer addition, the Townley Gallery,’ he said by way of greeting.

Imogene looked upward.

‘Gracious.’ Rilla followed her sister’s gaze. Three life-size giraffes stood at the top of the stairs. ‘They look so lifelike. I wonder how that effect is achieved.’

‘They have been specially preserved,’ Wyburn said. ‘We could enquire as to the scientific method if you’d like.’

‘That would be fascin—’ Rilla caught Imogene’s eye and stopped herself.

‘I wonder if giraffes ever get neck aches,’ Lady Wyburn said with one of her typical rapid-fire bursts of speech. ‘I recall my great-aunt Sarah used to have dreadful aches, particularly when it rained. And a giraffe would have such a lot of neck to ache. Perhaps that is why giraffes live in sunny climes.’

‘Perhaps,’ said Lord Wyburn.

Rilla saw the amused tolerance in his glance and felt herself warm to him.

I could almost like him. The thought flickered unbidden through her mind. She pushed it away. He was a viscount and one who, no doubt, still considered her likely to waste his stepmother’s money while swinging from trees or chandeliers.

Besides, he was too intelligent, too observant...the last sort of person with whom she should strike up an acquaintance. With this thought, she chose not to follow her relatives upstairs, but walked briskly towards the entrance of the new gallery which she had read contained the classical collection.

‘I believe the antiquities are unlikely to change in any marked degree within the next few moments.’ Lord Wyburn’s amused voice sounded from behind her. ‘Do you ever walk slowly or, perhaps, saunter?’

‘I don’t like to waste time. Besides, this is the Townley Gallery and I’ve heard wonderful things about it.’

The gallery was a long, rectangular room with large windows and fascinating circular roof lights providing an airy, spacious feeling. Despite her haste, Rilla paused on its threshold, surveying the statues and glass cases, instinctively savouring a delicious anticipation, an almost goosebumpy feeling of delight.

‘When I stood at the Parthenon, I thought I could hear the voices of the ancients. In here, I hear their echoes,’ Lord Wyburn said softly.

‘You really do love the antiquities,’ Rilla said.

She glanced at him. His chiselled features reflected his awe, wonder and curiosity. She had known no one, except her father, to understand or share such feelings.

‘I have always been fascinated.’

‘Have you visited Italy as well as Greece?’

‘And Egypt.’

‘You saw the pyramids?’ she asked, breathlessly.

‘Yes, they are as magnificent as ever, despite Napoleon.’

‘You are fortunate.’ She stepped towards the displays but jerked to a standstill. ‘Is—is that the Rosetta Stone?’

‘Yes, although many are disappointed...’

‘Disappointed?’ She stared at the pinkish stone. Tentatively she leaned towards it, pressing a gloved finger against the glass as though to feel its contours and trace the intricate inscriptions. ‘Don’t they understand? It is the key! The most exciting discovery. It may unlock the meaning of hieroglyphs and a whole culture from the past—’

She stopped and felt the heat rushing into her cheeks.

‘Passionate.’ He spoke so softly, she barely heard the word.

He stood beside her. She no longer resented his intrusion. Indeed, it felt as though they were removed from the outside world, just the two of them, and had found a kinship amid these past treasures.

She smelled the faint lingering scent of tobacco and heard the infinitesimal rustle of his linen shirt as it shifted against his skin. Even the air stilled, as though trapped like a fly in amber.

She swallowed, shifting, wanting to both hold on to this moment and, conversely, end it.

‘My father wanted to translate the Rosetta Stone,’ she said at last.

He straightened. She instantly felt his withdrawal as he stepped back and was conscious of her own conflicting sense of regret and relief.

‘I am not surprised. It is one of the most important discoveries in modern times. Has he been to the museum since it arrived?’ he asked.

‘No, I—he—’ London was not a good place for him, but she could not say that.

‘His responsibilities have been too great at home,’ the viscount said gently as though understanding that which she’d left unspoken.

‘Yes.’

And then it happened—without warning—without the usual feeling of dread or oppression. The present diminished. The man, the Rosetta Stone, the display cases, even the long windows dwarfed into minutia as though viewed through the wrong end of Father’s old telescope.

She felt cold, a deep internal cold that started from her core and spread into her limbs.

A child—a boy—appeared to her. She saw him so clearly that she lifted her hand as though to push aside the wet strands of hair that hung into tawny, leonine eyes. He stared at her, his gaze stricken with a dry-eyed grief.

She recognised those eyes. ‘I— What’s wrong?’

‘Miss Gibson?’ the viscount spoke.

She blinked, the boy still remaining clearer than the man or the museum.

‘Miss Gibson,’ the viscount said again.

‘You were so young—’

‘What?’ He thrust the word at her, a harsh blast of sound.

‘When she died.’

The boy vanished.

‘Who died?’ Lord Wyburn asked as the present sharpened again into crisp-edged reality.

His eyes bore into her, his jaw tight and expression harsh. She dropped her gaze from his face, focusing instead on the intricate folds of his neck cloth.

What had she said? What had she revealed?

‘Has my stepmother been speaking about me?’ A twitch flickered under the skin of his cheek.

‘No, we didn’t, I—’ she said, then stopped.

‘I will not be the subject of gossip and you will not do well in London if you cannot be appropriate in word and deed.’

A welcome surge of anger flashed through her. ‘I am visiting a museum, that is scarcely inappropriate.’

‘Discussions of a personal nature are unseemly.’

‘Then I will endeavour to discuss only the weather or hair ribbons.’

‘Good.’

He made no other comment and the silence lengthened, no longer easy. She wanted to speak, to cover this awkwardness but, after that momentary anger, lassitude filled her.

This often happened. Exhaustion leadened her limbs only to be replaced later by a need to run, to jump, to ride. None of which she would do here, of course.

‘Wonderful! There you are!’ Lady Wyburn’s sing-song tones rang out.

Rilla turned gratefully as Lady Wyburn and Imogene appeared at the doorway.

‘No doubt you are both entranced with these ancient objects, but I admit I am done with them,’ Lady Wyburn announced.

‘Indeed, let’s go.’ The wonders of the Rosetta Stone had dissipated and Rilla longed for her own company.

As they walked through the corridor and into the entrance way, she could feel Lord Wyburn’s silent scrutiny and her sister’s concerned gaze.

Only Lady Wyburn seemed impervious to any discord and happily related a discussion with Lady Alice Fainsborough. Apparently, they had met Lady Alice while admiring the giraffe on the second floor.

‘A lovely girl,’ Lady Wyburn said as the wizened caretaker pushed open the oak door. ‘Although unfortunately she resembles her mother with her propensity for chins. Still, it is good to know a few people prior to your début and one cannot hold her chins against her.’

The door creaked closed as they exited into the dampness of the London spring. Rilla exhaled with relief as if leaving the museum made her less vulnerable.

The rain had stopped, but the cobblestones gleamed with damp and raindrops clung to twigs of grass, glittering as weak sunlight peeked through still-heavy clouds.

But the smell—it was the smell she noted.

Earlier, the courtyard had smelled of fresh grass, mixed with the less pleasant odour of horse manure or sewage from the Thames. Now it smelled of neither. Instead, it was sweet, cloying and strangely old-fashioned.

She wrinkled her nose. ‘Lavender. I smell lavender.’

Lord Wyburn stopped. She felt the jerk of his body beside her.

‘I hate lavender,’ he said.

* * *

Even hours later, Paul could feel his bad humour as he sat astride his mount. Ironically, his own ill temper irritated. There was no sensible reason for it and he had no tolerance for moods. Rotten Row was pleasant and unusually quiet and while the clouds looked dark, it had not rained.

He rolled his shoulders. They felt tight as bands of steel. Amaryllis Gibson had unnerved him. The way she’d looked at him or through him as though seeing too much or not seeing at all. And her change from vivacious interest to unnatural stillness.

And lavender.

Why had she smelled lavender? No one smelled lavender on a London street.

His fingers tightened on the reins. Responsive to the movement, Stalwart shook his head with a metallic jangle.

Paul had hoped a pleasant ride and fresh air would calm him. It hadn’t.

All this nonsense about a début. He should have put a stop to the business. Now, he could only hope that his stepmother got both girls married off expeditiously so that he would have little reason to spend time in their company.

A sudden thundering of hooves grabbed his attention. He swung about as a horse going much too fast cut obliquely across his path. Stalwart snorted, stamping his hooves and shifting in a nervous sideways dance.

Instinctively, Paul soothed his mount, even as he tracked the other horse. Some crazy pup, no doubt. Thank goodness the park was unusually empty.

Except—the rider rode side-saddle.

‘Blast!’

Paul spurred Stalwart ahead, but the other animal had the advantage of several seconds and Stalwart was already winded. Hunkering close to his animal’s neck, Paul pushed the horse as fast as he dared and, squinting, discerned a woman’s form, her turquoise habit bright against the horse’s flank. Her hair had loosened, falling over her shoulders in a brilliant red-gold mass.

Paul gripped the reins tighter still. He knew only one woman with hair like that.

Irritation and a deeper, more primitive emotion clawed at him. Sweat dampened his palms. He was gaining ground. He’d be able to grab her reins soon enough.

He must be careful not to startle her animal. For a moment he imagined her thrown, her face smashed or her body crippled.

Half-standing in the stirrups, he leaned forward, his thighs clamped hard around the horse’s chest.

Then, without warning, her horse slowed.