Полная версия

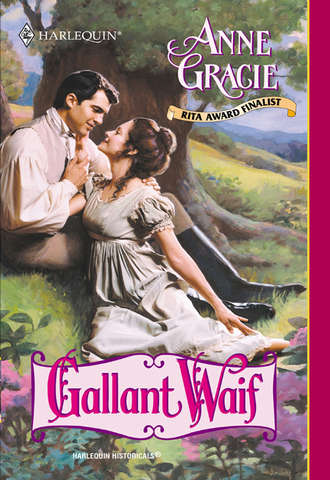

Gallant Waif

Squaring her shoulders, Kate took a deep breath and opened the door. Before her stood an imperious little old lady clad in sumptuous furs, staring at her with unnervingly bright blue eyes. Behind her was a stylish travelling coach.

“Can I help you?” Kate said, politely hiding her surprise. Nothing in Mrs Midgely’s letter had led her to expect that her new employer would be so wealthy and aristocratic, or that she would collect Kate herself.

The old lady ignored her. With complete disregard for any of the usual social niceties, she surveyed Kate intently.

The girl was too thin to have any claim to beauty, Lady Cahill decided, but there was definitely something about the child that recalled her beautiful mother. Perhaps it was the bone structure and the almost translucent complexion. Certainly she had her mother’s eyes. As for the rest…Lady Cahill frowned disparagingly. Her hair was medium brown, with not a hint of gold or bronze or red to lift it from the ordinary. At present it was tied back in a plain knot, unadorned by ringlets or curls or ribands, as was the fashion. Indeed, nothing about her indicated the slightest acquaintance with fashion, her black clothes being drab and dowdy, though spotlessly clean. They hung loosely upon a slight frame.

Kate flushed slightly under the beady blue gaze and put her chin up proudly. Was the old lady deaf? “Can I help you?” she repeated more loudly, a slight edge to her husky, boyish voice.

“Ha! Boot’s on the other foot, more like!”

Kate stared at her in astonishment, trying to make sense of this peculiar greeting.

“Well, gel, don’t keep me waiting here on the step for rustics and village idiots to gawp at! I’m not a fairground attraction, you know. Invite me in. Tush! The manners of this generation. I don’t know what your mother would have said to it!”

Lady Cahill pushed past Kate and made her way into the front room. She looked around her, taking in the lack of furniture, the brighter patches on the wall where paintings had once hung, the shabby fittings and the lack of a fire which at this time of year should have been crackling in the grate.

Kate swallowed. It was going to be harder than she thought, learning humility in the face of such rudeness. But she could not afford to alienate her new employer, the only one who had seemed interested.

“I collect that I have the honour of addressing Mrs Midgely.”

The old lady snorted.

Kate, unsure of the exact meaning of the sound, decided it was an affirmative. “I assume, since you’ve come in person, that you find me suitable for the post, ma’am.”

“Humph! What experience do you have of such work?”

“A little, ma’am. I can dress hair and stitch a neat seam.” Neat? What a lie! Kate shrugged her conscience aside. Her stitchery was haphazard, true, but a good pressing with a hot flatiron soon hid most deficiencies. And she needed this job. She was sure she could be neat if she really, really tried.

“Your previous employer?”

“Until lately I kept house for my father and brothers. As you can see…” she gestured to her black clothes “…I am recently bereaved.”

“But what of the rest of your family?”

This old woman was so arrogant and intrusive, she would doubtless be an extremely demanding employer. Kate gritted her teeth. This was her only alternative. She must endure the prying.

“I have no other family, ma’am.”

“Hah! You seem an educated, genteel sort of girl. Why have you not applied for a post as companion or governess?”

“I am not correctly educated to be a governess.” I am barely educated at all.

The old lady snorted again, then echoed Kate’s thought uncannily. “Most governesses I have known could barely call themselves educated at all. A smattering of French or Italian, a little embroidery, the ability to dabble in watercolours and to tinkle a tune on a pianoforte or harp is all it takes. Don’t tell me you can’t manage that. Why, your father was a scholar!”

Yes, but I was just a girl and not worth educating in his eyes. In her efforts to control the anger at the cross-questioning she was receiving, it did not occur to Kate to wonder how the old woman would know of her father’s scholarship. If Mrs Midgely wished Kate to be educated, Kate would not disappoint her. Some women enjoyed having an educated person in a menial position, thinking it added to their consequence.

“I know a little Greek and Latin from my brothers—” the rude expressions “—and I am acquainted with the rudiments of mathematics…” I can haggle over the price of a chicken with the wiliest Portuguese peasant. It suddenly occurred to Kate that perhaps Mrs Midgely had grandchildren she wished Kate to teach. Hurriedly Kate reverted to the truth. It would not do to be found out so easily.

“But I cannot imagine anyone offering a tutor’s position to a female. I have no skill with paints and have never learnt to play a musical instrument…” No, the Vicar’s unwanted daughter had been left to run wild as a weed and never learned to be a lady.

“I do speak a little French, Spanish and Portuguese.”

“Why did you not seek work as a companion, then?”

Kate had tried and tried to find a position, writing letter after letter in answer to advertisements. But she had no one to vouch for her, no references. Someone from Lisbon had written to one of her female neighbours and suddenly she was persona non grata to people who had known her most of her life. It hadn’t helped that the girl they remembered had been a wild hoyden, either. There were many who had predicted that the Vicar’s daughter would come to a bad end. And they were right.

Life in service wouldn’t be so bad, she told herself. As one of a number of servants in a big house, she would have companionship at least. A servant’s life would be hard, harder than that of a companion, but it was not hard work Kate was afraid of—it was loneliness. And she was lonely. More lonely than she had ever thought possible.

Besides, a companion might be forced to socialise, and Kate had no desire to meet up with anyone from her previous life. She might be recognised, and that would be too painful, too humiliating. She had no wish to go through that again, but none of this could she explain to this autocratic old lady.

“I know of no one who would take on a companion or governess without a character from a previous employer, ma’am.”

“But surely your father had friends who would furnish you with such?”

“Possibly, ma’am. However, my father and I lived abroad for the last three years and I have no notion how to contact any of them, for all his papers were lost when…when he died.”

“Abroad!” the old lady exclaimed in horror. “Good God! With Bonaparte ravaging the land! How could your foolish father have taken such a risk? Although I suppose it was Greece or Mesopotamia or some outlandish classical site that you went to, and not the Continent?”

Kate’s eyes glittered. Old harridan! She did not respond to the question, but returned to the main issue. “So, do I have the position, ma’am?”

“As my maid? No, certainly not. I never heard of anything so ridiculous.”

Kate was stupefied.

“I never did need a maid anyway, or any other servant,” the old lady continued. “That’s not what I came here for at all.”

“Then…then are you not Mrs Midgely, ma’am?” Kate’s fine features were lit by a rising flush and her eyes glittered with burgeoning indignation.

The old lady snorted again. “No, most decidedly I am not.”

“Then, ma’am, may I ask who you are and by what right you have entered this house and questioned me in this most irregular fashion?” Kate didn’t bother to hide her anger.

Lady Cahill smiled. “The right of a godmother, my dear.”

Kate did not return the smile. “My godmother died when I was a small child.”

“I am Lady Cahill, child. Your mother was my goddaughter.” She reached up and took the girl’s chin in her hand. “You look remarkably like your mother at this age, especially around the eyes. They were her best feature, too. Only I don’t like to see those dark shadows under yours. And you’re far too thin. We’ll have to do something about that.”

Lady Cahill released Kate’s chin and looked around her again. “Are you going to offer me a seat or not, young woman?”

This old lady knew her mother? It was more than Kate did. The subject had been forbidden in the Vicarage.

“I’m sorry, Lady Cahill, you took me by surprise. Please take a seat.” Kate gestured to the worn settee. “I’m afraid I can’t offer you any refresh—”

“Never mind about that. I didn’t come here for refreshments,” said the old lady briskly. “I’m travelling and I can’t abide food when I’m travelling.”

“Why did you come here, ma’am?” Kate asked. “You’ve had little contact with my family for a great many years. I am sure it cannot be chance that has brought you here just now.”

Shrewd blue eyes appraised her. “Hmm. You don’t beat around the bush, do you, young woman? But I like a bit of plain speaking myself, so I’ll put it to you directly. You need my help, my girl.”

The grey-green eyes flashed, but Kate said quietly enough, “What makes you think that, Lady Cahill?”

“Don’t be foolish, girl, for I can’t abide it! It’s clear as the nose on your face that you haven’t a farthing to call your own. You’re dressed in a gown I wouldn’t let my maid use as a duster. This house is empty of any comfort, you can’t offer me refreshment—No, sit down, girl!”

Kate jumped to her feet, her eyes blazing. “Thank you for your visit, Lady Cahill. I have no need to hear any more of this. You have no claim on me and no right to push your way into my home and speak to me in this grossly insulting way. I will thank you to leave!”

“Sit down, I said!” The diminutive old lady spoke with freezing authority, her eyes snapping with anger. For a few moments they glared at each other. Slowly Kate sat, her thin body rigid with fury.

“I will listen to what you have to say, Lady Cahill, but only because good manners leave me no alternative. Since you refuse to leave, I must endure your company, it being unfitting for a girl of my years to lay hands on a woman so much my elder!”

The old lady glared back at her for a minute then, to Kate’s astonishment, she burst into laughter, chuckling until the tears ran down her withered, carefully painted face.

“Oh, my dear, you’ve inherited you mother’s temper as well as her eyes.” Lady Cahill groped in her reticule, and found a delicate lace-edged wisp which she patted against her eyes, still chuckling.

The rigidity died out of Kate’s pose, but she continued to watch her visitor rather stonily. Kate hated her eyes. She knew they were just like her mother’s. Her father had taught her that…her father, whose daughter reminded him only that his beloved wife had died giving birth to a baby—a baby with grey-green eyes.

“Now, my child, don’t be so stiff-necked and silly,” Lady Cahill began. “I know all about the fix you are in—”

“May I ask how, ma’am?”

“I received a letter from a Martha Betts, informing me in a roundabout and illiterate fashion that you were orphaned, destitute and without prospects.”

Kate’s knuckles whitened. Her chin rose proudly. “You’ve been misinformed, ma’am. Martha means well, ma’am, but she doesn’t know the whole story.”

Lady Cahill eyed her shrewdly. “So you are not, in fact, orphaned, destitute and without prospects.”

“I am indeed orphaned, ma’am, my father having died abroad several months since. My two brothers also died close to that time.” Kate looked away, blinking fiercely to hide the sheen of tears.

“Accept my condolences, child.” Lady Cahill leaned forward and gently patted her knee.

Kate nodded. “But I am not without prospects, ma’am, so I thank you for your kind concern and bid you farewell.”

“I think not,” said Lady Cahill softly. “I would hear more of your circumstances.”

Kate’s head came up at this. “By what right do you concern yourself in my private affairs?”

“By right of a promise I made to your mother.”

Kate paused. Her mother. The mother whose life Kate had stolen. The mother who had taken her husband’s heart to the grave with her…For a moment it seemed that Kate would argue, then she inclined her head in grudging acquiescence. “I suppose I must accept that, then.”

“You are most gracious,” said Lady Cahill dryly.

“Lady Cahill, it is really no concern of yours. I am well able to look after myself—”

“Pah! Mrs Midgely!”

“Yes, but—”

“Now, don’t eat me, child!” said Lady Cahill. “I know I’m an outspoken old woman, but when one is my age one becomes accustomed to having one’s own way. Child, try to use the brains God gave you. It is obvious to the meanest intelligence that any position offered by a Mrs Midgely is no suitable choice for Maria Farleigh’s daughter. A maidservant, indeed! Faugh! It’s not to be thought of. There’s no help for it. You must come and live with me.”

Come and live with an aristocratic old lady? Who from all appearances moved in the upper echelons of the ton? Who would take her to balls, masquerades, the opera—it had long been a dream, a dream for the old Kate…

It was the new Kate’s nightmare.

For the offer to come now, when it was too late—it was a painful irony in a life she had already found too full of both pain and irony.

“I thank you for your kind offer, Lady Cahill, but I would not dream of so incommoding you.”

“Foolish child! What maggot has got into your head? It’s not an invitation you should throw back in my face without thought. Consider what such a proposal would involve. You will have a life appropriate to your birth and take your rightful position in society. I am not offering you a life of servitude and drudgery.”

“I realise that, ma’am,” said Kate in a low voice. Her rightful position in society was forfeited long ago, in Spain. “None the less, though I thank you for your concern, I cannot accept your very generous invitation.”

“Don’t you realise what I am offering you, you stupid girl?”

“Charity,” said Kate baldly.

“Ah, tush!” said the old lady, angrily waving her hand. “What is charity but a foolish word?”

“Whether we name it or not, ma’am, the act remains the same,” said the girl with quiet dignity. “I prefer to be beholden to no one. I will earn my own living, but I thank you for your offer.”

Lady Cahill shook her head in disgust. “Gels of good family earnin’ their own living, indeed! What rubbish! In my day, a gel did what her parents told her and not a peep out of her—and a demmed good whipping if there was!”

“But, Lady Cahill, you are not my parent. I don’t have to listen to you.”

“No, you don’t, do you?” Lady Cahill’s eyes narrowed thoughtfully. “Ah, well then, help me to stand, child. My bones are stiff from being jolted along those shockin’ tracks that pass for roads in these parts.”

Kate, surprised but relieved at the old lady’s sudden capitulation, darted forward. She helped Lady Cahill to her feet and solicitously began to lead her to the door.

“Thank you, my dear.” Lady Cahill stepped outside. “Where does that lead?” she asked, pointing to a well-worn pathway.

“To the woods, ma’am, and also to the stream.”

“Very pleasant, very rural, no doubt, if you like that sort of thing,” said the born city-dweller.

“Yes, ma’am, I do,” said Kate. “I dearly love a walk through the woods, particularly in the early morning when the dew is still on the leaves and grass and the sun catches it.”

Lady Cahill stared. “Astonishing,” she murmured. “Well, that’s enough of that. It’s demmed cold out here, almost as cold as in that poky little cottage of yours. We’ll resume our discussion in my coach. At least there I can rest my feet on hot bricks.”

Kate dropped her arm in surprise. “But I thought…”

The blue eyes twinkled beadily. “You thought you’d made yourself clear?”

Kate nodded.

“And so you did, my dear. So you did. I heard every word you said. Now, don’t argue with me, girl. The discussion is finished when I say it is and not before. Follow me!”

Gesturing imperiously, she led the way to the coach and allowed the waiting footman to help her up the steps. Swathed in furs, she supervised as Kate was similarly tucked up with a luxurious fur travelling rug around her, her feet resting snugly on a hot brick. Kate sighed. It seemed ridiculous, sitting in a coach like this, to discuss a proposal she had no intention of accepting, but there was no denying it—the coach was much warmer than the cottage.

“Comfortable?”

“Yes, I thank you,” Kate responded politely. “Lady Cah—”

The old lady thumped on the roof of the coach with her cane. With a sudden lurch, the coach moved off.

“What on earth—?” Kate glanced wildly around as the cottage slipped past. For a moment it occurred to her to fling herself from the coach, but a second’s reflection convinced her it was moving too fast for that.

“What are you doing? Where are you taking me? Who are you?”

The old woman laughed. “I am indeed Lady Cahill, child. You are in no danger, my dear.”

“But what are you doing?” demanded Kate in bewilderment and anger.

“Isn’t it obvious?” Lady Cahill beamed. “I’ve kidnapped you!”

Chapter Two

“But this is outrageous!” Kate gasped. “How dare you?”

The old lady shrugged. “Child, I can see you’re as stubborn as your dear mother and, to be perfectly frank, I haven’t the time to waste convincing you to come and stay with me instead of hiring yourself out as a maid or whatever nonsense you were about. I intend to reach my grandson’s house in Leicestershire tonight and, as it is, we won’t reach it until well after dark. Now, be a good girl, sit back, be quiet and let me sleep. Travelling is enough of a trial without having a foolish girl nattering at me.” She pulled the furs more closely around her and, as if there was nothing more to be said, closed her eyes.

“But my house…my things…Martha…” Kate began.

One heavy-lidded eye opened and regarded her balefully. “Martha knows my intentions towards you. She was most relieved to hear that you would, in future, make your home with me until such time as a suitable husband is found for you. A footman is locking up your house and will convey the keys to Martha.”

Kate opened her mouth to speak, but the blue eyes had closed implacably. She sat there, annoyed by the ease with which she had been tricked, and humiliated by the old lady’s discovery of her desperate straits. She sighed. It was no use fighting. She would have to go wherever she was taken, and then see what could be done. The old lady meant well; she did not know how ill-placed her kindness was.

…until such time as a suitable husband is found for you. No. No decent man would have her now. Not even the man who’d said he loved her to distraction wanted her now. She stared out at the scenery, seeing none of it, only Harry, turning away from her, unable to conceal the revulsion and contempt in his eyes.

Harry, whom she’d loved for as long as she could remember. She’d been nine years old when she first met him, a tall, arrogant sixteen-year-old, surprisingly tolerant of the little tomboy tagging devotedly along at his heels, fetching and carrying for him and his best friend, her brother Jeremy. And when Kate was seventeen he’d proposed to her in the orchard just before he’d left to go to the wars, and laid his firm warm lips on hers.

But a few months ago it had been a totally different Harry, staring at her with the cold hard eyes of a stranger. Like all the others, he’d turned his back.

Kate bit her lip and tried to prevent the familiar surge of bitter misery rising to her throat. Never, ever would she put herself in that position again. It was simply too painful to love a man, when his love could simply disappear overnight and be replaced with cold disdain…

The coach hit a deep rut and the passengers lurched and bounced and clung to their straps. Kate glanced at Lady Cahill, but the old lady remained silently huddled in her furs, her eyes closed, her face dead white beneath the cosmetics. Kate returned to her reflections.

So she would never marry. So what? Many women never married and they managed to lead perfectly happy and useful lives. Kate would be one of them. All she needed was the chance to do so, and she would make that chance; she was determined. Maybe Lady Cahill would help her to get started…

Bright moonlight lit the way by the time the travelling chaise pulled into a long driveway leading to a large, gloomy house. No welcoming lights were visible.

In a dark, second-floor window a shadowy figure stood staring moodily. Jack Carstairs lifted a glass to his lips. He was in a foul temper. He knew full well that his grandmother would be exhausted. He couldn’t turn her away. And she knew it, the manipulative old tartar, which was, of course, why she had sent her dresser on ahead to make things ready and timed her own arrival to darkness. Jack, in retaliation, had restricted his grandmother’s retinue to her dresser, sending the rest off to stay in the village inn. That, if nothing else, would keep her visit short. His grandmother liked her comfort.

The chaise drew to a halt in front of a short flight of stairs. The front door opened and two servants, a man and a woman, came running. Before the coachman could dismount, the woman tugged down the steps and flung open the door. “Here you are at last, my lady. I’ve been in a terrible way, worrying about you.”

Lady Cahill tottered unsteadily on her feet, looking utterly exhausted. Kate felt a sharp twinge of guilt. The old lady clearly wasn’t a good traveller, but Kate’s attempts to make her more comfortable had been shrugged aside with so little civility that, for most of the journey, Kate had ignored her.

Kate moved to help but the maidservant snapped, “Leave her be. I will take care of milady. I know just what needs to be done!” Scolding softly, she gently shepherded the old lady inside, the manservant assisting.

The chaise jerked as it moved off and Kate almost fell as she hastily scrambled out of it. She took a few wavering steps but, to her horror, her head began to swim and she swirled into blackness.

The man watching from the window observed her fall impassively and waited uninterestedly for her to scramble to her feet. No doubt this was another blasted maid of his grandmother’s. Jack took another drink.

Damned fool that he was, he’d clearly mishandled his sister, refusing to see her. He’d been heavily disguised at the time, of course. Even drunker than he was now. Good thing his grandmother hadn’t asked to see him tonight. He’d have refused her too. Jack continued staring sourly out of the window, then leaned forward, intent. The small, crumpled figure remained motionless on the hard cold gravel.

What was wrong with the girl? Had she hurt herself? It was damned cold out there. Any more time on the damp ground and she’d take more than just a chill. Swearing, he moved away from the window and limped downstairs. There was no sign of anyone about. He heard the sound of voices upstairs—his grandmother was being tended to by the only available help. Jack strode into the night and bent awkwardly over the small, still figure.

“Are you all right?” He laid his hand lightly on the cold cheek. She was unconscious. He had to get her out of the cold. Bending his stiff leg with difficulty, he scooped her against his chest. At least his arms still had their strength.

Good God! The girl weighed less than a bird. He cradled her more gently. Nothing but a bundle of bones!

Jack carried her into the sitting-room and laid her carefully on a settee. He lit a brace of candles and held them close to her face. She was pale and apparently lifeless. A faint, elusive fragrance hovered around her, clean and fresh. He laid a finger on her parted lips and waited. A soft flutter of warm breath caused his taut face to relax. His hands hovered over her, hesitating. What the deuce did you do with fainting females? His hands dropped. Ten to one she’d wake up and find him loosening her stays and set up some demented shrieking!