Полная версия

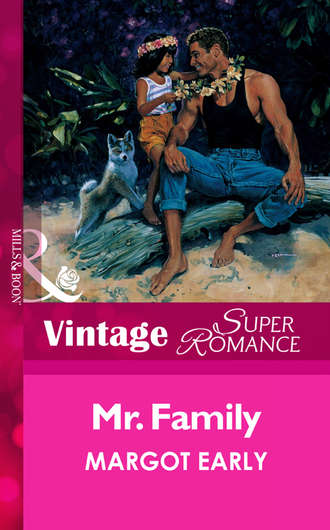

Mr. Family

The script was small and lightly etched, the letters running almost straight up and down.

Dear Mr. Ohana,

As Kurt Vonnegut says, “There’s only one rule that I know of—” It applies to child rearing as to anything.

“Damn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

Sincerely,

Ms. Aloha

“So what do you think?”

Kal hadn’t known Danny was paying attention. Even now, he was swinging Hiialo back to an upright position, his eyes on his niece.

Kal stuffed the card back into its envelope—another mainland address—tossed it on the stack with the rest and stood up. Taking Hiialo from Danny and feeling the comfort of her small slender arms circling his neck, Kal told his brother-in-law, “I think this was a stupid idea.”

“What was stupid?” asked Hiialo. Then, seeing Jakka emerge from the hallway, she said, “What was that song you were playing, Jakka?”

Danny burst out laughing, and Jakka approached Hiialo, threatening to tickle. “You didn’t like my song?”

Hiialo grinned, and Jakka ruffled her hair affectionately. He met Kal’s eyes, his own apologizing for his earlier remark. “I miss our band.”

Kal thought, I miss her. He’d lost all his music in one bad night.

“Laydahs, yeah?” Jakka squeezed Kal’s shoulder briefly, then wandered out onto the lanai, down the steps and into the rain.

As Jakka crossed the tiny lawn to stand beside the zebra-striped door of his cousin’s lavender-and-green VW bus, Danny lingered on the porch. “You got to be kind,” he mused. Swiftly he executed a ka hola, four bent-legged steps to one side and back to the other, his hands and muscular arms saying aloha. “I like Ms. Aloha.” With a last tug on Hiialo’s hair, he turned and leapt down off the porch and into the rain.

“Danny!” In Kal’s arms, Hiialo perfectly and gracefully imitated her uncle’s aloha, eliciting approving laughter from Danny and Jakka. Stirring useless pangs in Kal’s heart.

Wish you could see her, Maka…

As his friends climbed into the Volkswagen and the bus backed out and disappeared down the wet driveway, Hiialo pulled the sleeve of Kal’s T-shirt. “Can we go to the gas station and get shave ice? Eduardo’s hungry.”

“That mo’o is going to eat up my last dollar on shave ice.”

“Please?” Hiialo smiled at him from her eyes, from ear to ear, from her heart. “And can we stop and see Grandma and Grandpa at the gallery? I have a picture for them.”

Her grin made him grin, too. So much like someone else’s smile…Kal asked, “You know who has the best smile on this whole island?”

Hiialo kissed him. “My daddy.” She slid down, starting for her bedroom, knowing they would go get shave ice.

“Put on a shirt,” he called after her.

“I know,” she said, as though he were so tiresome. “I have to dress like a girl.”

DAMN IT, YOU’VE GOT to be kind.

Kal turned again on his mattress, trying to quiet his mind—and ease the burning in his gut. But the moon outside was too bright, and tonight he couldn’t make his breath match the rhythm of the waves hitting the shore just two hundred yards away. He shifted his chest against the bottom sheet, wishing he could sleep. His fingers spread on the mattress, and he remembered touching something more.

But this bed, the captain’s bed he’d built of koa just to fit his small room, this bed was only wide enough for him and then some—Hiialo when she bounced up beside him with a book in the mornings, wanting him to read to her.

Hiialo…Shave ice…His eyes closed, and his mind, drifting off, played music. His own. Chords. Finger-picking…

He opened his eyes and stared without focus at a groove in the paneling beside his bed. Sitting up, Kal grabbed a pair of loose cotton drawstring shorts beside the bed and pulled them on.

He put his bare feet on the floor and reached past his two packed bookshelves, filled with humidity-warped paperbacks, music books, lives of musicians. His fingers grasped the neck of the Gibson L-50, familiar as the limb of a lover, and he pulled it from its hanger on the wall. As he slipped out of the room, he passed the other instrument still hanging, the shiny chrome National etched with palms and plumeria, and those in cases on the floor, the Stratocaster and the Les Paul. The guitars saved him each night. Companions in the emptiness of forever. Loyal as dogs.

In the dark, he went into the narrow front room and pushed aside the hanging curtain to look in on Hiialo. She slept in one of his puka T-shirts—full of holes. Her mouth was open, her legs uncovered. Kal drew the quilt back over her.

“Thank you, Daddy,” she murmured in her sleep.

“I love you, keiki.” She made no response, and Kal headed out onto the lanai through the open front door.

He inhaled the ocean and the flowers, the jasmine crawling up the wood rails, and as he sank down on the tired porch swing and stared at the plants in the moonlight, he felt the water hanging everywhere in the air.

A sprawling blue house with an oriental roof, a vacation rental owned by his parents, stood between the bungalow and the beach. No view from his place, but Kal could hear the ocean and the insects, the bugs of the wet season. He saw the gray shape of a gecko doing push-ups on the porch. Watching it, he reached for the unseen with his mind and his soul.

Nothing.

Where are you? he thought. I need you.

It was one of those nights.

She was dead.

He strummed his guitar, tuned up in the moonlight. A flat, F minor, B flat seven…“The Giant was sleeping by the highway/winds called pangs of love brewed on the sea…” The words were symbols of Kauai and of his life—with her and without her. “Why didn’t you wake up, Giant?/Why didn’t you wake up and save me?”

He sang into the night, the act of singing easing tension in his abdomen, and he didn’t hear the sound of feet. But he noticed the small body climbing up onto the swing beside him.

Fingers still, he stopped singing. “I’m sorry, Hiialo. Did I wake you?”

She shook her head, her lips closed tight, middle-of-thenight tears-for-no-reason nearby.

Kal rested the old archtop in the swing, the neck cradled in a scooped-out place in the arm. It was a system he often used—for holding a guitar so that he could hold Hiialo at the same time. He lifted her into his lap and cuddled her against him.

“I don’t like that song,” she said. “It’s sad.”

That was true. And the song was true. Mountains didn’t rise up to stop fate. Kal hadn’t been able to, either. Not the accident. Or Iniki, the hurricane.

It wasn’t a truth for children.

“Want to hear ‘Puff’?” Kal had played “Puff the Magic Dragon” too many times in bars in Hanalei to consider it anything but agonizing. Still, it was Hiialo’s favorite, and maybe Puff could wipe that teary sound out of her voice.

But Hiialo shook her head, snuggling closer against his chest.

Five seconds, and she’d say, Wait here, and dash off to get her blanket and a stuffed thing called Pincushion that Kal couldn’t remember where or when she’d gotten. Whenever she tried that trick, he’d get her back into bed, instead. If allowed, she would stay up all night.

Like him.

Hiialo whispered, “I wish you weren’t sad.”

Something shook in Kal’s chest. He opened his mouth to say, I’m not sad. But he never lied to her.

He hadn’t known he seemed sad.

“You make me happy, Hiialo. The best part of my day is seeing you after work and finding out what you’ve been doing.”

Hiialo’s little fingers touched the few dark golden hairs on his chest. “Will you tell me a story about my mommy?”

Kal winced.

“Tell me about when you were in the band in Waikiki and Mommy—”

“How about not?” He kept his voice light. “But I’ll play ‘Puff.’”

She shook her head. He took a breath and watched the trade winds make some nearby heliconia, silver under the full moon, wave back and forth like dancers. Maka had moved like that.

Gone.

In a weary tone of resignation, Hiialo said, “I’ll hear ‘Puff.’”

“What an enthusiastic audience we have tonight.” Kal set her on the swing beside him, then picked up his guitar. As he started to play and sing about the dragon, he thought, I’m not the only one who’s sad.

Hiialo couldn’t remember. But she felt the void.

Later, after he’d tucked her in with Pincushion and the invisible Eduardo, Kal went to get his guitar and hang it up in his room, and on the way he noticed the paper grocery bag into which he’d stuffed the letters to Mr. Ohana.

Damn it, you’ve got to be kind.

Yes, he thought. Be kind to my daughter.

He put away the Gibson, and then returned to the front room that was kitchen and dining room and living room crammed into a hundred square feet. He grabbed the grocery sack, took it to the boat-size chamber where he slept, turned on his reading light and dumped out the letters on his bed.

He had to push them into a heap to make a place to sit, and then he read them and dropped them, one by one, back into the paper bag on the floor. He’d work up a form reply to the letters. Thank you for responding to my ad in Island Voice…Good luck in life and love. Sincerely, Mr. Ohana.

Only one note he laid aside, without taking the card from the envelope. He could cut out the picture of the girl and the dolphin and give it to Hiialo to tack on the wall of her room.

Damn it, you’ve got to be kind.

Finally he took an old spiral notebook and a pen from his desk drawer, and he lay on his bed and wrote a letter he didn’t intend to send to a woman he’d never met. The bag of letters on the floor seemed pathetic—answers from a sad but hopeful world to an even more pitiable plea. But their collective refusal to despair gave him a fleeting, moonlight-made hope. And after he signed the letter, “Sincerely, Kalahiki Johnson,” he got up and pulled open another drawer, the big bottom drawer, and drew out the shoe box full of photos.

Pushing aside the cassette case that lay on top, cached among things he loved, he flipped through the snapshots, careful of fingerprints. Careful of his own eyes. Pictures still hurt.

The photo Christmas card showing the three of them was near the top. It seemed right. Stealthily, not wanting to wake Hiialo, not wanting his actions to be known in the light of day, he went out to the kitchen to find scissors and finally picked up Hiialo’s green-handled little-kid scissors from the floor by the couch. Biting closed his lips, his eyes blurring in the ghostly gray dark, he cut apart the photo.

Maka’s arm still showed, stretched across his waist as she touched Hiialo, and for a moment Kal pondered how to remove it. But at last he left it, because then Ms. Aloha would understand what he’d tried to say with words.

CHAPTER TWO

Santa Barbara

ERIKA COMMITTED HERSELF to overcoming fear of risk. In the days after she answered Mr. Ohana’s ad, she photographed scenes on the streets of Santa Barbara. A pink poodle outside Neiman-Marcus. Children giving away kittens in front of the supermarket. She spent as much time petting the poor dyed dog as photographing it, and she wanted to adopt a kitten. Instead, she developed the pictures and painted from them, telling herself this was the kind of gamble she’d promised to take. These were not women by the sea.

But what would Adele say? Would she say that Erika might lose her following? If her art stopped selling, if she had to get another job, she would die. Flower without water. Painting was all she had.

Erika’s reaction to the possibility was detachment; she tried to feel equally aloof about the other risk she’d taken. Answering a personal ad.

So when she pulled bills and catalogs out of her post-office box and saw a number 10 envelope hand-addressed to Ms. Aloha, she muted her feelings. The response had come from K. Johnson, Box J, Haena, Kauai.

K. Johnson.

Mr. Ohana.

She didn’t open the letter in the post office or when she reached the Karmann Ghia parked at the curb. Instead, she set her mail in the seat beside her and drove down State Street toward the harbor. She parked in the marina lot, in Jake Donahue’s space. Jake was her brother’s business partner and sometimes first mate on his ship. Jake was going to be in Greenland with David until June, and Erika was boat-sitting his Chinese junk, the Lien Hua. It was a usual sort of living arrangement for her.

Temporary.

Erika collected the mail and her shoulder bag and crossed the boardwalk, pausing at a gate in the twenty-foot chain link fence outside Marina C. She used Jake’s key card to open the lock and made her way down the creaking dock. Erika was painfully familiar with the harbor. It was where she had lived with her brother and his son on David’s old ship, the Skye. It was where she had lived During.

That was over, she reminded herself again. This was After.

Memories of that earlier time would always be with her. Some things shouldn’t be forgotten. Some things couldn’t be.

She reached the Lien Hua’s berth. Walking alongside the junk to its stern, she caught her muted grayish reflection in the dingy glass windows. Tall. Rayon import dress. Hair that fell several inches below her shoulders, neither smooth nor curly, brown nor blond, but simply nondescript.

Erika unlocked the cabin of the junk and ducked through the hatch, descending into the two-room space that contained all her worldly goods and most of Jake Donahue’s. Her art supplies lay on the fold-out kitchenette table. Unfinished watercolors covered the meager wall space in places where the sunlight wouldn’t fade them.

She tossed her mail on the narrow bunk where she slept. K. Johnson’s letter was on top, but Erika resisted picking it up, tearing it open. Restraint was possible through routine.

She opened the overhead hatch, then dropped down a companionway to the unlit galley. In the gloom, the light on Jake’s answering machine glowed steadily. No messages. From the small icebox run on dockside electricity, she took a bottle of fresh carrot juice. Erika removed the lid and sipped at it.

Suddenly she could wait no longer. She capped the juice, put it back in the refrigerator and returned to the salon and her mail.

She took K. Johnson’s letter topside, where the air smelled of beach tar, and settled in a wooden deck chair in the shade of the mast. The closest sailboats were deserted, covered. Opening the letter, Erika was glad of the solitude, glad her brother was faraway across a continent and an ocean, glad Adele was across another, glad no one could know that she’d done this insane thing. That she, a thirty-six-year-old woman, had answered a personal ad involving a celibate marriage.

And a four-year-old girl.

As she withdrew the letter and unfolded it, something dropped into her lap. A photo, upside down. Erika didn’t look. She put her hand against it, protecting it from the breeze, and turned to the page. The letter was written in black ballpoint pen on warped paper torn from a spiral notebook. Neat male handwriting.

Dear Ms. Aloha,

My name is Kalahiki Johnson, though you know me as Mr. Ohana, who placed a personal ad in Island Voice. I am thirty years old, and I was born and raised on the island of Kauai, where my father’s family has lived for six generations and where I work as a tour guide on the Na Pali Coast.

My four-year-old daughter is named Hiialo, pronounced Hee-AH-lo, which means “a beloved child borne in the arms.” Soon Hiialo will be too big to carry, but she will always be the most precious thing in my life.

Hiialo’s mother was my wife, Maka. Maka was a hula dancer and chanter who won competitions in hula kahiko, traditional hula, and also in hula auana, modern hula, both of which tell stories. She was a kind and graceful human being in every way, and we loved each other deeply. Three years ago, driving back from a hotel where she’d been dancing, she was killed in a head-on collision.

Erika set down the letter, biting her lip, unable to read on.

She’d thought that he was some yogi who’d taken a vow of abstinence. Or maybe that he was impotent or burned out on relationships. She’d wondered about Mr. Ohana’s reasons for wanting a celibate marriage, but she hadn’t expected anything like this. Though she should have.

Why was it affecting her this way? And she was affected, her eyes hot and blurry, her heart racing with horror, as though she’d just learned of the death of someone she loved.

And he was only thirty.

Since then I have raised Hiialo alone, but I work long hours, and it’s hard on her. I wish there was someone who could do what Maka would have done for our daughter and who would love Hiialo as she did.

If you are still interested in Hiialo and me, please write back. But understand that even if a permanent domestic arrangement is possible, your relationship with me would be platonic. Maka and I were married for seven years, and no one can replace her in my heart. I want no other lover, and I would prefer to live alone, if not for Hiialo. Please understand this, because, as you said, we all need to be kind.

Sincerely,

Kalahiki Johnson

Erika put the heel of her hand against her mouth, pressed her lips together. In her mind, she heard an echo of the past, and she couldn’t shut it out. One word repeated itself.

David.

Her brother.

For the three years after his first wife’s death, Erika had lived with him. For three years, she had been a mother figure to his son, Christian. That had been the best experience of her life, though it had begun out of duty. There had been much entangled pain—David’s and her own, both caused by the same woman.

But this situation was different. So different.

Talk about risk.

The winter breeze pushed at her hair, and Erika reached for the photo in her lap, so that it wouldn’t blow away. She turned it over, and her breath caught when she saw him.

He was a beautiful man.

Light brown hair, still damp from a swim, stood out in short uncombed spikes, as though he’d just come out of the water and shaken it. His lean muscular chest and arms were tanned the color of oak. The child’s skin, the skin of the almost-toddler in his arms, was a shade darker. And darker yet was the rounded well-toned female arm brushing his body, the hand touching the baby.

Maka. He’d cropped her from the shot, all but her arm.

Erika absorbed every detail of the picture. The sea. The man’s smile. His grin came from sensuous lips and slitted dark-lashed eyes of uncertain color and, clearly, from his heart. Anyone could see he held the baby often. Erika saw gentleness and love between the child in her green swimsuit and the man who held her in front of him, feet out to face the camera. Somehow the baby had been coaxed into a dimply laugh, and Erika wondered if her father’s fingers cupped under one small bare foot were responsible.

The picture was like a book, and when she read it she cried.

Erika heard the dock creak and saw a couple who owned a sloop two berths down approaching. Not wanting to talk, she stood up and limped to the cabin door, slipped inside. The junk rocked gently. She listened to the lapping of water, to some wind chimes outside. The monotonous music of solitude.

Her heart felt simultaneously fearful and excited.

He had answered her letter. From however many replies he’d received, Kalahiki Johnson had chosen hers. His answer had contained no proposal of marriage, no promises. Just an invitation to write back.

She lay down on her bunk and read it again.

Twice.

Three times.

The light faded outside, and she turned on the lamp over the bunk and studied the photograph and the letter, memorizing the words, especially the last paragraph.

A sensible part of her, the part that was the older sister of a man who’d lost his wife, wanted to step back and say, “Oh, Kalahiki, you’re young. You’ll fall in love again.”

But the photograph won a debate words would have lost. And Erika resisted admitting even to herself that he did not seem a man destined to live out his life in celibacy.

I have to tell him.

She would have to tell him about herself. Reveal her past to a stranger and hazard rejection because of it. It would be unconscionable not to tell him, but the prospect was horrible.

Erika found comfort where she could.

I don’t have to tell him everything.

Haena, Kauai

KAL PEDALED HARD through the rain to the post office to collect his mail. The transmission on his car had given out, so that morning he’d cycled to the office of Na Pali Sea Adventures in Hanalei in the rain. He would get home the same way, in the dark, on one-lane roads and bridges, veering into the brush and mud when headlights approached. Raindrops clattered against the wide green leaves all around him as he pulled up outside the small building of the Haena post office. It was after five, so the counter was closed, but Kal could still go inside and open box J.

“Please, Mr. Postman…” He thought in music all his waking hours. He dreamed music in his sleep.

Rain dripped from him onto the stack of bills and flyers he drew from the box. The letter from Santa Barbara was on top. The return address sticker read “Erika Blade” and had a logo of an artist’s palette beside it. Alone in the office, he tossed the rest of his mail on a bench, sat down and opened the envelope, his curiosity stronger than his embarrassment over the letter he should never have mailed.

To Ms. Aloha.

Erika Blade.

She had sent another card. Same artist, different picture. A very old woman sitting in the sand, gazing out to sea. The ocean really looked like the ocean.

As Kal opened the card, the photo dropped out faceup.

A good-looking brunette in cutoffs and a faded T-shirt sat against the side of a weathered wooden building with a drawing board against her knees and a paintbrush in her hand. She had long muscular legs and a laughing smile.

A good smile.

But sunglasses hid her eyes.

Reflexively fishing for an antacid from a bottle in his pack, Kal studied every detail, down to the shape of her toes, before he turned to her small delicate handwriting, which covered the whole inside of the card and continued on the back. She had a lot to say, and as he chewed on a tablet, he read with curiosity, not with hope.

Dear Kalahiki,

Thank you for answering my note. Reading of your terrible loss made my heart ache. I am so sorry about your wife’s death, and I wish there were something I could do to ease your grief.

My conscience dictates that I precede this whole reply with the advice that you not marry anyone at this time. Despite the things you said in your letter, I believe there is more love in store for you. You should find it before marrying again—for your daughter’s sake and your own.

This is what I believe, but I can’t know your heart. Leaving your choices to you, I’ll introduce myself.

My name is Erika Blade. I am thirty-six years old and a watercolor artist. But probably, if my last name is familiar, it’s because my father was the undersea explorer Christopher Blade. My brother, David, and I grew up on his ship, the Siren, and accompanied him and my mother all over the world on scientific expeditions until I entered art school in Australia and began to make art my career. While I was at school, the Siren sank and my parents were killed. My brother continued my father’s work, and I have helped him some.