Полная версия

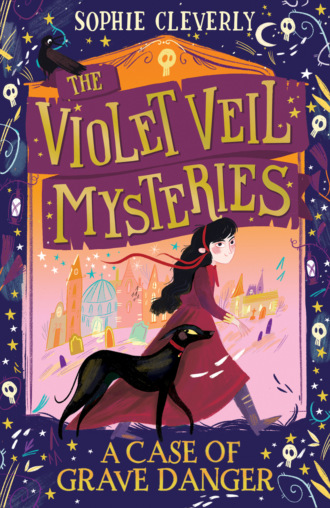

A Case of Grave Danger

Now Bones batted at the back door, whining. It was open a crack. Someone had come inside.

Or gone out.

After a deep breath, I pulled the door back a little and peered through. I could see nothing but rain. A lantern, I thought. That was what I needed. Father often kept one by the back door.

I snuck into the tiny cloakroom by the porch and pulled out a black overcoat that was a little too big for me, buttoning it on over my nightgown. Soft leather boots that were now old and battered went on over my feet – they felt odd without any stockings.

The glass lantern was on a hook next to the door, almost too high for me to reach, but I managed it on tiptoes. There was a white candle stub inside, so I found a box of matches and lit it. Then I took a deep breath. It was time for a very unwise decision.

I stepped outside.

The rain fell around me in waves, immediately sticking strands of my hair to my forehead. Gooseflesh rose on my legs in seconds as the wind bit into them. The light from the lantern illuminated only a mere few feet in front of my eyes. Bones quivered in the cold, before striding ahead into the dark.

There were fresh footprints in the mud, leading away from the house. Human footprints. Footprints that were just a little larger than mine.

Definitely an unwise decision.

As I went through our back gate, the footprints disappeared as the grass of the cemetery took over.

I began to walk through the graves. I knew them well. I passed John Beckington and steadied myself on the headstone. I passed Annie Arkwright and Mr and Mrs Jones and Jeremiah Heap. I stopped for breath by the O’Neill family crypt and leaned against the cold wall. The vast tomb gave a little shelter, at least.

If I listened hard enough, I could hear their whispers.

Keep going.

You’re close.

They sensed something that I could not. So far I had seen nothing but the faint grey shadows of the ghosts, which shifted and changed like wisps of fog. I had heard no movement in the grass or trees, no sounds of footsteps or heavy breathing. But it was so dark and so loud out there that I began to wonder if I wasn’t being totally foolish. Perhaps I had just imagined the footprints, the way they looked. Perhaps they had belonged to Thomas from earlier in the day, and I just hadn’t noticed them before.

The only way I would know if someone was there was if they jumped out at me, and that wasn’t an idea I relished. Bones was still moving forward, as if he had caught a scent.

I shivered. I was sure to catch a chill in this weather. ‘Who’s there?’ I whispered, blinking through the rain at the iron clouds and the few stars that dappled the empty space between. I wondered if I might hear a ghostly answer, but whatever I sensed from the dead, it was never an answer to my burning questions.

It was time to move on – I needed to keep going. I could see Bones running on ahead, investigating the graves as he passed. I decided I would loop back on myself once I got to the far hedgerow (I longed for my bed already), but I soon realised I was getting nearer to the spot where the blond boy was to be buried.

Bones stopped at the graveside, where the freshly dug hole gaped like the mouth of Hell. Then I really could hear something. A moaning sound that seemed as though it were coming from the grave.

I was near paralysed with fear. Bones hung close to my leg, and I felt his skin rumbling as he growled.

Slowly, I dangled the lantern and peered in.

The grave was empty. Nothing but a muddy hole, rapidly filling with rainwater.

The sound reached my ears this time. It was definitely someone moaning. I bit my lip so hard that I could taste blood.

‘H-hello?’ I called into the night. ‘Is someone there?’ I blinked in the rain, in the flickering glow of the candlelight.

Something moved behind one of the gravestones. A shadow, shuffling, ungainly.

Watch out, one of the ghostly voices whispered on the breeze.

I gasped, and Bones barked into the wind. The shadow moved nearer, pushing through the grass. I stayed frozen, held out the lantern like a shield. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to see what was approaching, but I had no choice.

A figure lurched into the light, and I caught a strangled breath in my throat.

There, standing before me, was the blond boy. The boy who was supposed to be dead.

I screamed.

Alive, the deathly voices around me echoed in whispers. Not one of us. This would be the talk of the graveyard now.

The blond boy was dressed in funeral finery, the best that could be put together for a pauper from the tailor’s cast-offs, but even so – his face was as pale as the moon above us, a sliver of it peeking through the dark clouds. He was soaked with rain, dishevelled and muddy, his hair sticking up at strange angles. His skin was ashen, his eyes sunken and hollow, blinking in the light.

I finally caught my breath again. ‘Are you all right?’

The boy stumbled towards me, and I jerked backwards. Bones barked again, a warning.

The boy opened his mouth, as if not quite sure how it worked. He rubbed a hand against the back of his head. ‘Where … am I?’ he asked, the words coming slowly like they were rising up through treacle.

I shushed Bones and held on to his collar. ‘You’re in the graveyard,’ I said. ‘Um, well, Seven Gates Cemetery, to be precise.’ I realised that I was going to have to step a little nearer, but my legs were fighting against me. I ignored them and moved closer to the boy so he could hear me.

‘Are you a ghost? Am I … dead?’ the blond boy asked, his dark eyes wide with terror.

I paused, a little taken aback by his humanity. Perhaps he wasn’t some terrifying creature of the night after all.

‘I’m certainly not a ghost!’ I said. ‘Ghosts are more …’ I looked down at myself. ‘See-through. And you certainly don’t look dead,’ I admitted. ‘In fact, you seem rather upright.’

The boy suddenly stumbled sideways, falling into the mud beside the grave. Bones pulled away from me and began to lick his face.

‘Violet! Violet! Are you there?’

It was Father! I had never been so thankful in my entire life. ‘Father! Come quick, please!’

He dashed through the darkness towards me, his hand shielding his eyes. ‘What on earth …’ he shouted as the water drummed on the stones around us. Bones pressed a wet nose against his trousers. My father was wearing nightclothes under an overcoat, like myself.

I watched as Father slowly took in the sight before him – the pouring rain, his daughter looking like a drowned rat, and the blond boy slumped against a stone cross, chest heaving with the breath of life.

‘Oh my …’ Father said, as though hardly able to believe his own eyes. He looked at me desperately. ‘What’s going on here?’

‘I don’t know!’ I said breathlessly. ‘I heard a noise, so I went downstairs, and I found his coffin empty! The door was open, and there were footprints …’

Father pulled me into his arms. There was a brief moment of warmth and shelter, before he released me. ‘You should have fetched me immediately! There could have been grave robbers about!’ His words were cut short as he looked at the boy again. I didn’t know how Father could see a thing – his spectacles were steamed up and splattered with rain. ‘How could this have happened?’ His face had gone as pale as the boy’s.

The boy shook his head as if trying to regain his senses, and shivered in the cold. He looked up at us, and finally spoke again. ‘W-what’s … happened to me?’

* * *

The blond boy was dead. He had been dead. Hadn’t he? He’d been sent to us to be buried – I’d seen it with my own two eyes. And yet, whatever he had been, he was very much alive now and firmly back in the land of the living.

Father held a shaking hand out to the boy. The boy took it, but it took several attempts to lift him up – his weakened legs kept buckling beneath him. When he was finally standing, he seemed to be capable of staying up. I wanted to take his hand so badly, to give him comfort in any way that I could, but Mother’s voice in the back of my head whispered that it would be improper.

He moaned again, and tried to bat the light away.

‘He’s delirious,’ Father said.

I gulped. ‘It’s all right,’ I said to the boy, trying my best to soothe his quick breaths. ‘Please, stay calm. We need to get you inside. Can you walk?’

‘I think so,’ he said, but his voice was barely a whisper, and I wasn’t sure whether I’d truly heard or only seen his lips move.

Father tentatively put his hands on the boy’s shoulders. ‘I’ll run for Doctor Lane. Violet will help you back to the house, if you can make it.’

The boy nodded again, silently, and I couldn’t help but shudder. I knew he was alive, but at the same time still felt as though he were a dead man walking. Like Frankenstein’s monster.

In the lamplight, I could see that he was covered with mud and damp grass. Bones gently licked him.

Then Father was running, and Bones shot away after him with a sudden burst of greyhound speed. They darted through the headstones like minnow through a stream – they knew them as well as I did.

The blond boy staggered again, and I ducked underneath his arm to try to bear him up. To heck with improper, I thought. He needs me. And I couldn’t keep calling him ‘the blond boy’. ‘What’s your name, master?’ I asked.

‘Oliver,’ he replied, and then he began coughing violently.

When the coughing subsided, I spoke again. ‘Can you walk? We’ll need to get you back to the house. You’ll catch your de—’ I stopped myself. ‘Sorry.’

He didn’t seem to notice my faux pas. He began to stumble forward, and together we walked back through the rain-washed graveyard, the mud and sodden grass threatening to pull our shoes from our feet. I tried to steer him around the graves, but at one point he tripped on Nathaniel Partridge’s broken headstone and nearly brought us both down.

It seemed like it took an age, the two of us walking in silence under the black sky. The ghosts’ voices were mere tingling whispers now – I fancied they were talking amongst themselves, not to me, about the evening’s excitement. The barrier between living and dead was a hard one to cross, like shouting underwater.

As the clouds began to melt away, I glimpsed stars beginning to twinkle. ‘Not long now,’ I kept saying. ‘Nearly there.’ Eventually it was true, and we were outside the back door.

It was wide open – Father must have run through the house.

The boy – Oliver – stopped and leaned against the wall, his breathing still rapid. One of his hands clutched his stomach, the other his head. I quickly reached inside the door and stretched to hang up the lantern on the hook, so that I had both hands free.

‘Please … Master Oliver,’ I said. ‘You’ve got to get inside.’

He looked at me, and I was suddenly struck by his eyes, which were – for all their sunkenness – a deep, dark brown like a warm cup of cocoa. So different from my own, which were storm grey.

‘I …’ he paused. ‘I don’t want to tread mud inside your house, miss.’

And then he fainted.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.