Полная версия

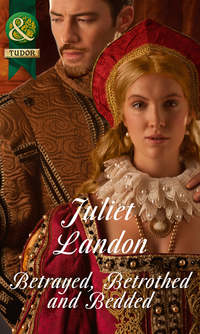

Betrayed, Betrothed and Bedded

‘Yes, otherwise you’d not have stayed at court for a month, would you? I’m talking about your lack of good manners towards me, and you know that I am. You also know why I’ve come here and there’s nothing you can do to change that. Once His Grace has decided, no woman will undecide him, so you may as well accept it and come off your high horse, lady.’

‘Or there will be penalties. I see. Well, that must be the most subtle inducement I’ve ever received. Guaranteed to succeed with disobedient hounds, hawks and horses, I suppose, but women? I’m not so sure. Me, I’m quite sure it would fail dismally. So sorry. Try again.’

Like a firework, their conversation had sparked into the antagonism lying dormant between them for weeks, Ginny’s resentment simmering beneath the surface, Sir Jon’s usual assuredness on hold, waiting for the right time. Forced into a confrontation by the king’s own needs, the right time was still some way off, and Sir Jon’s only option was to tackle the problem head-on. Subtlety was going to be of little use here, he’d decided. Bracing himself against the wall with both hands, he effectively caged her with his bulk, making it impossible for her to complete the irritable flounce away to one side. ‘No, mistress! That’s the first thing you’ll learn not to do when I’m talking to you. Stand still and listen.’

‘I shall not listen.’

‘I think you will. Your manner towards me before others will be polite and respectful at all times. I do not care what you try on in private. I can deal with that in my own way. But do not seek to chasten me by pretending I’m not there, as you have done at court.’

‘I can choose who I speak to, sir.’

‘Not anymore, you can’t. None of us can. We must be civil to everyone these days or make enemies of those who have the means to harm us. You should have learnt that by now. You’re about to enter a different world from this—’ he tipped his head towards the silver-grey garden ‘—where a harsher set of rules applies and, if you have the common sense your father tells me of, then you’ll allow yourself to be schooled by one who knows them well.’

‘Yourself, of course.’

‘That’s the king’s wish and your parents’, too.’

‘And how much is the king paying you to take on this onerous task, Sir Jon, since nothing my father could offer you three years ago was enough? How many abbeys has he promised you? Which particular titles did he bribe you with?’

There was time enough for her words to fade away on the ice-cold air before he replied, searching her eyes as if to see behind them. ‘My, you are a bittersweet little termagant, aren’t you, mistress? Is that’s what’s been eating at you for three years?’

‘How could it, sir? We have seen nothing of each other until recently.’

‘And now we have? Still resentful?’

‘I resent being commanded to wed a man who has to be enticed so openly and expensively, sir. What woman could possibly be flattered by that?’

‘Wait a minute. That’s not the answer, is it? You’ve only just found out about the king’s wish, so why the cold shoulder at court?’

‘I really don’t know what you mean. I’m not one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting, nor even one of her maids. I have not felt obliged to mingle as they do. We may be neighbours here in Hampshire, Sir Jon, but that doesn’t mean we have to like each other. You made your indifference plain from the start. Why should I not do the same?’

‘I have never been indifferent, Mistress D’Arvall. I was obliged to bide my time, that’s all.’

‘Ah, yes, of course. Biding your time. That’s done rather differently at court, I notice. A command from the king can make all the difference to one’s timing, can it not? There, I see that’s hit the nail on the head.’

His head had dropped between his powerful shoulders as she laid bare the facts about timing and, when he lifted it, she could hear how the soft laughter caught at his words, feel the warmth of his breath, and smell the male odour of skin. Standing upright to release her, he replaced the black-velvet cap on his head as a sign that their conversation must end. ‘Correct,’ he said, smiling still. ‘A king’s command is a powerful thing, but don’t forget who else stands to gain from it, mistress. Your family. All of them. Does that mean so little to you? There was a time, I believe, when you would have needed no persuading.’

Freed from his closeness, she pulled her cloak farther around her neck and faced the door, through which shouts could be heard. ‘Do try to understand me, Sir Jon, if you will. I am as set against the king’s command, and my father’s, as it is possible to be. If I could find a way out of it, I would. Persuasions are superfluous, aren’t they, when consent has been removed? It’s one thing to be noticed by the king and to have the honour of being his friend, but it’s quite another when he tells me who I should marry. It would matter little who you were, sir. My resentment would be the same.’

His arm came across her once more, preventing her first step. ‘And you should try to understand me, mistress, when I say that your reasons are far from watertight. But we’ll let that go for lack of time. Just remember what I said to you about a more respectful demeanour, for I’ll not be made to look foolish by a woman again.’ Dropping his arm, he moved away to open the garden door, and there was no time to ask what he meant by that before the king’s hounds came bounding forwards to greet them. Sir Jon was relieved by not having to find an answer to his slip of the tongue, as he was by the controversial question of penalties, for if she had asked for examples, he would not have been able to invent a single one.

* * *

No one could fail to be impressed by King Henry, for if size alone had been a measure of kingship, he would have won hands down. At forty-nine years old, his girth had expanded to enormous proportions, exaggerated by the winter bulk of padding and furs, making the whippet-like figure of Sir Walter D’Arvall look like a toy beside him. The heavy fur-lined gown was thrown back to expose a chest like a house side, encrusted, embellished, puffed, slashed, and hung with chains and pendants as big as tartlets. Everything about him was large except his prim little mouth and glittering beady eyes that darted over the top of Lady Agnes’s head as he raised her to her feet with gentle courtesy. His eyes alighted at last on Ginny, standing with the escort she had not planned to meet until much later, when it suited her. ‘Ah, there you are, Mistress D’Arvall. Are you glad to see me again?’

Ginny came forwards to make a low curtsy. ‘Indeed, Your Grace. As are we all. Welcome to our modest home,’ she said, already practised in deflecting Henry’s attention from herself to more general themes. This occasion was going to require all her wits to stay out of deep waters, and Sir Jon’s presence would hardly make things any easier. His appearance beside her was immediately remarked on.

‘Raemon! Didn’t lose much time in finding her, did you? Eh? Made any progress, or is it too soon?’

Sir Jon had expected this kind of tactlessness. It was Henry’s privilege. One either had to squirm and accept the humiliation, bluff it out with similar frankness or stand on one’s dignity. ‘Like you, sire, I made good haste,’ he said, smiling. ‘As would any man.’

Henry nodded, satisfied. ‘Your brothers are here, too,’ he said to Ginny. ‘We must have them with us at such a time. Can’t leave them out, can we?’

‘Hawking is one of their favourite pastimes, Your Grace. You have chosen a perfect time for it, while the air is clear,’ she said.

His smile became paternal as he bent his head towards her. ‘Ah, mistress,’ he said, so close that she could smell his sour breath, ‘that was not my meaning. I invited your brothers along to witness your betrothal to this fine fellow here. Surely your lady mother has told you of our wishes?’

It took every ounce of Ginny’s self-control to stifle a cry of defiance at that, having only just learned who her eventual husband was to be, and that there was no way out of it. What was the urgency? Why now? Why the indecent haste for a betrothal, as if she might run away? Forlorn hope. ‘So soon?’ she whispered.

Taking her response for maidenly reticence, Henry glanced at Ginny’s parents, unable to conceal the desire in his piggy eyes. ‘Charming,’ he said. ‘What modesty. She does you credit. Now, Lady Agnes, a glass of your Rhenish would be more than welcome after that long ride. Eh?’ Leaning heavily on the arm of a well-dressed young man, he limped away towards the porch where the warmth of the great hall would begin the slow thaw of fingers and toes.

Yet despite Sir Jon’s recent warning to her, Ginny’s glare of sheer fury could not be held back and, though it was met by the unmistakable caution in his eyes, her snarled question found its mark. ‘You knew of this, didn’t you? Am I to be the last to know what’s going on here?’

‘Later,’ he whispered. ‘We’ll talk later.’

‘I’ll be damned if I’ll talk to you,’ she muttered, ‘or him.’

‘Shh! For pity’s sake, have a care, woman. He’s not deaf.’

Fortunately for Ginny, the hum of voices covered their heated exchange while Sir Jon’s hopes of a more compliant attitude from her seemed as far away as before. Obviously it would take more than a hurried warning to make any impression on this fiery creature with a resentment as deep as a well.

For a crowd of courtiers who had ridden hard all day to reach D’Arvall Hall, they still looked remarkably fine and free from the dust that, in summer, would have covered them from head to toe. Around her, the swish and rustle of rich fabrics mingled with excited chatter as skirts were lifted, cloaks trailed, and feathers waved like so many bright birds in an overcrowded aviary. The sheen of silver and gold woven into the silks caught the mellow light from the hall, though Ginny herself would never have ridden a horse wearing such costly garments. She was glad, however, that she’d taken time to dress with care in the pink velvet with the square neckline, the loose outer sleeves edged with her mother’s honey-coloured squirrel fur, the undersleeves of pale cream brocade. To her mother she had pretended not to care that her hair was of the same paleness, but a glance in the mirror had confirmed the radiant confidence that came with looking her best, no matter how dire the situation. ‘I shall give you Mistress Molly,’ her mother had said in an attempt to thaw the frostiness between them. ‘You’ll need a maid now and Molly knows your ways better than anyone. She can dress your hair.’

Ginny had thanked her without a smile, suspecting that Mistress Molly would be well rewarded for keeping Lady Agnes informed of all that happened, or did not happen, to the new Lady Virginia Raemon. So the sensational hair had been taken into plaits at each temple, then joined at the back to lie over the top of the rest. Now she felt, as well as saw, the looks directed her way from many of the courtiers she knew and who, until now, had thought her too innocent to include in their worldly conversations.

Her mother’s efforts had paid off: gleaming silver and glass on the tables, white napery, liveried servants, musicians up on the gallery, and the delicious aroma of food wafting through the openings of the elaborate wooden screens where tapestries made a splash of colour on adjacent walls. ‘Well, little sister?’ said a familiar voice behind her. ‘You’re going to take us all up in the world, are you? Can’t say I’m surprised. You could give young Kat Howard a run for her money any day. And the Basset girl, too.’ It was Paul, her brother, wearing a doublet of brightest yellow.

Before she could reply to his typically facile remarks, Sir Jon forestalled her with a more apt put-down than she could have devised. ‘Your sister is not in competition with Mistress Howard,’ he said, ‘nor will she ever be. As for going up in the world, that rests with His Majesty alone. Better get that straight, lad, before you get any more fancy ideas.’

Paul D’Arvall’s indiscretions had landed him in trouble more than once during his year at Henry’s court where he was tolerated for a particular aptitude for mimicry that had been known to take away the pain of Henry’s badly damaged leg. Time and again he had been forgiven and excused by Henry for misdemeanours that had had others banished, locked in the Tower, or worse, and others suspected that young D’Arvall felt himself perfectly safe as long as he could keep Henry amused. No reprimand from his father had made him more circumspect, and though his mother could see no fault in him, the rest of the family felt distinctly uncomfortable whenever he was around.

His brother-in-law, Sir George Betterton, was one of the few people to whom Paul would listen, occasionally, and now he happened to be standing with Sir Jon, his neighbour. ‘Best keep your opinions under your bonnet, D’Arvall,’ he said. ‘Such loose talk can get even you seen off with your tail between your legs.’ He winked at Ginny. ‘Hello, sister-in-law,’ he said kindly. ‘Maeve’s looking for you. Been hiding?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘What would you do?’

‘Oh, I’d certainly hide from this great brute.’ He laughed. ‘Come and talk to me and your sister. We’ll tell you how to handle him.’

But Ginny had seen her other brother, Elion, and her greeting was warmer by far than it had been for Paul, the younger of the two. ‘Dear one,’ she said. ‘Can we talk?’

‘Yes, love. But not until after supper, I fear, for here comes Father with that “now you listen to me” look on his face.’ He lifted his cap as Sir Walter approached. ‘Want me to stay, Ginny?’

His question was answered for him by the quick tip of Sir Walter’s head that usually left his subordinates in no doubt about what he intended. Even Sir Jon could only watch as Ginny’s arm was taken and she was steered towards a shadowy corner away from the bustle. Foolishly, in retrospect, Ginny hoped she might be allowed to have the first word. ‘Father, I know you mean well, but I did not agree to—’

Sir Walter knew immediately what she referred to. ‘So your mother tells me, Virginia,’ he cut in brusquely. ‘But what has that to do with anything? I agreed to it. So did His Majesty the king, and so did Sir Jon. Isn’t that enough? Who else is there to ask? God’s truth, lass, if we went round the countryside asking for opinions, you’d still be unmarried by Domesday. My duty is to find you a suitable husband and I’ve been lenient with you till now. But I shall not be here for ever and the king’s offer is as good as it’s going to get. You must accept it, for all our sakes. It means everything to your mother and me.’

‘Whether I like it or not.’

‘Yes. Whether you like it or not, young lady. And no more discourtesy towards Sir Jon, if you please. I could hardly believe you and he have not spoken in this last month at court. Have you no thought to the future?’

‘Yes’, she replied, she had, she did, ‘but—’

‘But nothing!’ Sir Walter snapped. ‘There are no buts in this business, Virginia. Men make the conditions, not women of your age. Just remember that, will you?’

‘Yes, Father,’ she responded as he walked away. He did not want answers, reasons, or opinions, only blind obedience, for this was not just about her, but about all he stood to gain by it. In one way or another, a man had to fight for his own advancement by any means open to him, for Henry had grown fickle, unpredictable, and not to be relied on for his favour. Whatever he offered must be snatched up with both hands before someone else benefited; families were at each other’s throats, seeking dominance and influence with a king who wanted those around him to agree with every word, to fawn and flatter, to pander to his monstrous ego. Those who were not prepared to do this had no place at court, and no place at court meant no share of the spoils being handed out almost daily, whether positions, titles, or one of the eight hundred or so monastic properties that had been closed down over the past five years. What were the preferences of a young woman worth compared to this?

Nevertheless, it seemed to Ginny that all this fuss simply to have her near the king at court as a married woman was completely ridiculous when he could command her presence at any time, married or not, and to enjoy her company whenever he wished. As he had done since she’d been with Queen Anna, his new wife, walking in the gardens, partnering him at bowls, riding out with hawks, sharing these pastimes with others of her own age until the queen from Cleves could converse in English to his satisfaction. Was this really worth the rewards her mother had told her of? Was there something more she might be expected to do? Was she being used by her family in the same way that plain Jane Seymour had been by hers? Evidently not, for Jane had taken no husband except the king himself, and now he had ‘a new wife he didn’t care for’...and rumour had it that the dear lady was still a virgin.

The hairs along Ginny’s arms prickled. Her scalp crawled. No...no, not that! Were her parents so insensitive that they could subject her to that? With an ageing king? And Sir Jon, too? Had he agreed that, for his rewards, he would allow his wife to be used? Her head reeled with the onrush of questions. She felt nauseous as a wave of cooking smells assaulted her nostrils. Where was Elion? Maeve? They would explain.

From above her, a fanfare of trumpets blasted out across the hall to tell them that supper was about to begin, for however much the king pretended that his informal visits needed no pomp or ceremony, he would not have been impressed if his hosts had taken him at his word. It was too late for Ginny to explore the details of the matter that would affect her for the rest of her life.

Amongst those who had come with the king that day, there were few who were unaware of the coolness between Mistress D’Arvall and Sir Jon Raemon, and now some had even placed bets on how long it would take him to thaw the lady who must have some very serious reasons for her dislike. She must rate herself very highly, they thought, to place herself so far beyond his reach when he was one of the most eligible of the king’s gentlemen, wealthy, accomplished, intelligent, and devastatingly good-looking. So it was with some anticipation that the handsome couple was observed together at the table where their demeanour could be judged and the stakes raised accordingly.

But as if in unspoken accord, neither Ginny nor Sir Jon would give them the satisfaction of having anything to gossip about, and to all eyes it looked as if Ginny was prepared to accept the role being thrust upon her, whatever it was, and to be the meek and submissive daughter her father required. The truth was that she would not shame her family, or Sir Jon, in public before the king, although what she did in private would be an entirely different matter. Knowing her as they did, her family was not fooled, and nor was Sir Jon, who did not know her half so well, but had observed her more keenly than she realised. He had seen how her father had spoken to her, how she had paled and how he would not have minced his words. Having gained some idea from their brief talk together how her mind was so set against him, he was thankful, but not optimistic, about her show of obedience.

The lavish supper passed off without incident, King Henry’s occasional references to Ginny’s talents and Sir Jon’s eagerness being taken good-naturedly by them, while she raged inside at all those who sought to manipulate her life for their own selfish ends. There was a point during the banter when, under cover of the noise, Sir Jon murmured to her, ‘Well done, mistress. I know what this is costing you in restraint.’

‘Do you, Sir Jon? I very much doubt it.’

‘Believe me, I do. They’re like a dog with a bone. They’ll let it go eventually.’

Warming to his role as matchmaker, and assuming that Ginny would be of the same mind as any young woman ripe for marriage, Henry lost no time after supper in bringing the two of them together in a public manner intended to show off his great benevolence, as if his motives were entirely selfless. Upstairs, in the beautiful oak gallery, he took Ginny by the hand while beckoning Sir Jon to stand close by, past the silk-clad legs and crackling skirts, the smiling faces and nudging elbows, causing a silence to descend as he took centre stage. ‘Mistress D’Arvall,’ he said in his rasping tenor, ‘since this sluggard has not seen fit to find you for himself, I present him to you now for your approval. It is our wish, and that of your parents, that you and Sir Jon should plight your troth at some time during our visit. You, sir, are most fortunate. Mistress D’Arvall is a prize worth winning.’ He looked down at Ginny with such unconcealed lust that, for once, his next words only squeaked and had to be repeated. ‘He will...ahem...he will make you a good and honest husband, mistress. We commend him to you.’

‘I thank you, your Majesty, but...’

‘Sir Jon, you may take the lady’s hand.’

With every eye upon them, Ginny placed her fingers lightly on Sir Jon’s rock-solid palm to support her curtsy as the applause and smiles added yet another layer of finality, already too deep for her liking. She felt the net closing around her and pulling her wherever Sir Jon went and nowhere she wanted to be. Certainly not at court and certainly not anywhere near the husband of the woman she had come to admire. She would be moulded to other men’s lives, given over to their desires with all her dreams of love fading in one handclasp. He took her hand to his lips, bowing courteously, putting on a good act, Ginny thought, of being pleased by the king’s generosity. Her own eyes were downcast, her heart heavy with foreboding, for this handsome creature who had once rejected her would surely have a woman of his own somewhere, maybe one of those watching this charade. Their hearts would probably weigh as heavy as hers. Perhaps they had already planned how to deal with it.

Heavy-hearted or not, Sir Jon concealed it well as he led her through the crowd to meet well-wishers, to acknowledge smiles, slaps on the back for him, and kisses for her from those she would now have to learn to like. Drawn this way and that, parted from Sir Jon, she came face-to-face once more with her brother Paul, his friends already laughing at his witty remarks, the content of which Ginny could easily guess. She would have smiled and moved away in search of her sister, but Paul would not allow the chance to escape him and, leaning heavily against her with his lips close to her ear, he mimicked the king’s words of a moment earlier. ‘He’ll make you a good and honest husband, mistress,’ he said in the reedy royal tone. ‘And do you see that lust in my eyes, too, sweet wench? I’ll have you in my bed tonight, sweet Virginia. Sir Jon won’t mind if I have you first, eh?’ Laughing at his own adolescent jest, he swung her round by the waist in a parody of a dance until she was caught and held by Maeve, who would not share Paul’s sport at her expense.

Nor did George, her husband, whose hand held the back of Paul’s embroidered collar as if he were an ill-trained pup. ‘Go and sit down, D’Arvall,’ he said in a low angry voice. ‘The wine’s gone to your head, lad. You’ll go too far one day if you’re not more careful.’ He gave him an ungentle shove into the arms of his companions.

‘I said nothing!’ Paul protested. ‘I was only...’

Sir George turned back to the two sisters and saw by Ginny’s white face that her brother’s ‘nothing’ was far from the truth. People moved away sympathetically, leaving them to find a bench at the end of the long gallery beneath a dark portrait of their grandfather. ‘What is it, Ginny?’ Maeve said. ‘What did Paul say?’

‘He said...well, he seemed to be saying that this is all for the king’s convenience and that Sir Jon wouldn’t mind. Which is what I’d already begun to suspect. Is it true, Maeve? Is this what the king does when he takes a mistress? I’ve not been at court long enough to know how these things are done, but not for one moment did I imagine the king would already be in need of a mistress when he’s only been married a month or so. Tell me it’s not true.’

The brief glance exchanged between Maeve and her husband was loaded with anguish. ‘Listen, love,’ Maeve said, taking Ginny’s hand upon the rich green brocade of her skirt. ‘We hoped Mother would have made the position clear to you by now. And Father, too. They know how these things go.’