Полная версия

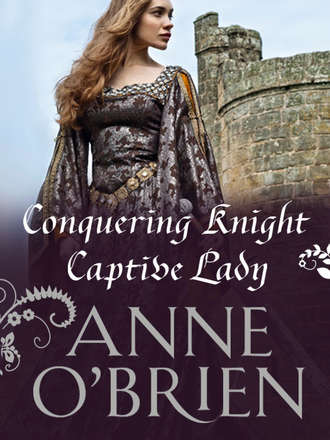

Conquering Knight, Captive Lady

Her Wild Hawk. Her Fierce Lord.

Gervase Fitz Osbern.

That one man … Some four years since now. The memory of him came easily into Rosamund’s mind, as if it had slid there before, at regular intervals, along a well-worn path. The man who had descended on Salisbury in the foulest of humours to hold a dangerously fraught interview with the Earl. She had never known exactly why. But a bucketful of bad blood had existed between Fitz Osbern and Earl William from the very beginning, obvious in the crackle in the air and the imminent threat of drawn blades as they exchanged views. And the Earl had planned to smooth the waters, to entice this enemy into an alliance. So he had offered Rosamund to him, to lure him into taking a Longspey wife.

She remembered as if it were yesterday being summoned so that the lord might look her over.

But he had not looked her over. He had barely cast an eye in her direction, after that first vicious stare when she had entered the room. He had not even done her the courtesy to appraise her merits as a bride. And after all her mother’s efforts to turn her out at her best, threading emerald ribbons through her braided hair. What an arrogant appraisal it had been before he turned his shoulder, one brief raking glance from head to foot that had all but stripped the clothes from her body. Even now at this distance she re-lived the moment that had brought a rush of unflattering colour to her cheeks and an edge to her temper. Not that he had noticed. The formidable knight was too busy refusing Earl William’s offer to consider her appearance or her feelings at being so summarily rejected. She had been dismissed almost before she had set foot in the room.

You would buy me with a Longspey woman? You’ll not succeed. There’s blood on your hands, my lord, that can’t be washed away by the gift of a simpering Longspey virgin.

The hard-held fury, the harsh menace in his voice. The shame that she had felt as if his rejection of her had been due to some fault of her own. It remained with her still, as did a clear image of the man’s face and stature. He might not have taken more than a passing acknowledgement of her but, no simpering maid at twenty years—and she doubted she had ever been known to simper!—Rosamund’s fascinated stare had been as direct and all-encompassing as his had not.

The Wild Hawk he had become in her dreams, savage and untamed, never knowing the hood or jesses, the leash of the falconer. What a pleasure he had been to look at. Tall and lean with the well-muscled body of a soldier, a lord who would ride and fight, a master of weaponry, although on this occasion he was richly dressed, with embroidered bands at hem and sleeve of his tunic. He might wear a sword, but the leather belt was gilded and jewelled. He had obviously come to make an impression. If she concentrated, even now she could imagine his dark hair, grey eyes, gold-flecked. Eagle features, she remembered. A will of tempered steel. Now, what would it have been like to wed such a man as he?

Barely polite, he had been uncomfortably forthright. I don’t seek a marriage with one of yours. One of his more discreet opinions. But then that one sweep of his hard grey eyes was an insult in itself. All I demand from you, my lord, is the return of my father’s property and recompense for the untimely death of my wife. If she had wed the Wild Hawk, he would not have let her have her own way, that’s for sure. He would order and demand and insist at every turn. Rosamund shivered at the prospect. That would be almost as bad as wedding Ralph de Morgan! Despite her own preoccupations, she found it in her heart to feel pity for the Wild Hawk’s poor dead wife.

Her breath hitched a little. At the last he had, surely against his will, touched her once. As he marched to the door, furiously disappointed, he was forced to pass within an arm’s length of her. He had stopped abruptly, thrust out his hand in command. She had placed hers there.

‘My lady!’

And he had kissed her fingers. Fleetingly. Mouth and hand as cold as his ire was hot. Yet it had burned her, the heat of it slamming her senses. She still recalled it, as if the brand were still there. Imagined in her moments of despair what it would be like to feel the insistent pressure of those lips on hers, the slick knowledge of his tongue, those hands against her breast where her heart pounded for some desired outcome of which she had no experience …

Rosamund blinked away the scene. Well, the outcome of the clash between two such strong-willed men had put paid to any such possibility of the man taking her to his bed. The Wild Hawk hadn’t got the land or the recompense he sought, Earl William had not got his alliance and she hadn’t got a husband. Her unwilling lover had stiffened, his head bent, hair curling like black silk against her wrist. Then he had dropped her hand as if it had scorched him, leaving her without a backward glance. That was the last she heard of him.

And yet, Rosamund had found those strong features haunting her thoughts. Not a handsome man, his features too harsh for pure symmetry, but an arresting one. A powerful man with a dark glamour who would draw the eyes of any woman. A man who would let nothing stand in his way of seizing what he wanted. What would it have been like to have wed that Wild Hawk, to be his and his alone? To have given up her prized virginity to a man who prowled and smouldered and demanded. Four years on and she was still in possession of that prize, and no one valued it—except the despicable Ralph. She would probably take it to her grave. What value then?

‘Rose …’

She blinked again, aware that her mother was beginning to fret under her own fierce and protracted stare. That was all long ago. Now her Hawk was probably as fat and unappetising as Ralph de Morgan, living in some cold secluded castle with a wife and children around his feet. Without doubt, he would have ridden roughshod over her just as much as the de Longspeys, which would not have been to her taste.

‘Well, Rose, if Gilbert is set on it—’ Petronilla’s voice broke in to her uneasy recollections ‘—how can we stop it?’

A glint appeared in Rosamund’s eye, which should have warned her mother. ‘I know exactly how to do so. I am going to take up my inheritance.’

‘In Clifford?’

‘Yes. It’s mine and I can live there if I wish. You can come with me or go to Lower Broadheath. Will you come?’ A little smile touched her lips as she watched Petronilla consider, knowing the outcome. Of course her mother would come. She would admit that to change Rosamund’s mind would be like trying to change the direction of the wind, and she might as well save her breath, but she was not so careless a parent as to allow her only child to journey into the wild terrain in the west unaccompanied.

‘I will come with you,’ Petronilla confirmed. ‘Of course I will. Do you need to ask?’ And then, with a sigh as reality struck, ‘But Gilbert will stop you.’

‘No, he won’t. I have a plan.’

‘But, Rose, it’s so far.’

‘Exactly! Far enough to get me out of the marriage with Ralph de Morgan. Once there, I’ll be safe. I can live as I wish.’ Rosamund’s eyes gleamed with indomitable courage and sheer excitement at the planned adventure. ‘If I flee to Clifford, rejecting all ties with Salisbury, Gilbert—and Ralph too—might just write me off as a lost cause. I doubt either of them will bother to send a force after us, to drag me back to Salisbury in chains or lock me in a dungeon until I am obedient. We shall both be free of the selfish demands of opinionated men. Which, I think, will suit both of us very well.’

Chapter Two

Fitz Osbern arrived in Hereford as the winter night closed in, rain still falling steadily. He settled his men as usual into the range of buildings that made up the Blue Boar, stayed only for a cup of ale, a platter of bread and tough meat of dubious origin, then replaced cloak and hood to begin a round of the ale houses and taverns.

Knowing the habits of his quarry, it did not take long. In the Red Lion he caught sight of just the man who would answer his needs. A thickset soldier with years of experience on his shoulders, he was in the act of raising a tankard to his lips, Fitz Osbern strode up behind him and clapped him on the back. He choked over the ale.

‘God damn it!’ The irate drinker wheeled round, tankard discarded so that it rolled wetly on the table. His hand flashed to the dagger at his waist, all the honed instincts of a hardened campaigner, until he grunted, grinned as he wiped his hand down over the front of his ale-spotted tunic. ‘Ger! I might have known. But you might value your life …’ Hugh de Mortimer swept the point of the short-bladed dagger in a menacing circle, before placing it on the table top and pushing forward a stool with one booted foot.

‘As if you could stick me with that pretty toy, before I had you on the floor under my boot.’ Gervase sat, cast off his cloak. ‘Still frequenting stews such as this for your entertainment?’ His lips curled at the rank smoke, the unpleasant mix of scents of rancid onions and sour ale, of damp and unwashed humanity. Hugh’s weathered face softened into a smile of easy camaraderie of long standing, which Gervase returned as they finally clasped hands in greeting. Hugh continued to wear his years well. There were a good dozen years between them, but they had fought side by side over those years to keep the March at peace. Grizzled, stocky, the Marcher lord enforced his authority with steely blue eyes and a common touch that made him popular and easy to approach.

‘For your information, Ger, I’m here for any news of interest,’ the Marcher lord chided gently, yet with the authority of experience and the scattering of grey in his hair. From his power base in Hereford, Hugh de Mortimer had taken it upon himself to keep his finger on the tumultuous pulse of the March in the name of the King. ‘I had a meeting with one of my informants here.’ Hugh eyed Gervase, the growth of beard, the black, rain-matted hair. ‘Thought you were in Anjou.’

‘I was. Just returned.’ Stretching out his right leg, a groan indicating a recent injury from a fall from his horse, one that still ached in cold wet weather, Gervase ran his hand over his rough chin and cheeks with distaste. ‘Some hard travelling with little time for home comforts. As for the crossing …’ His expression said it all. ‘I was bound for Monmouth. And then I heard some interesting news on the road this side of Gloucester.’

A gleam lit the keen blue eyes. ‘Salisbury?

‘Salisbury. That’s why I’m here. I thought you’d know more if there was anything to know. Your lines of communication are excellent. Tell me what’s afoot.’

‘Salisbury’s dead,’ Hugh confirmed, turning smartly to business. ‘That’s what you wanted to hear.’

‘So it’s true.’

‘And you are thinking of the future of Clifford.’

‘How would I not?’

‘That this is your chance to get it back?’

‘I don’t know. I doubt it. The son and heir has as much an iron fist as his father. The lands will be held secure. I doubt the change in ownership will make much difference. And I’m too far stretched with the Anjou possessions to engage in a major conflict, however much I might desire the castle.’

Hugh’s hand closed over the Fitz Osbern’s wrist, pulled him closer. ‘But listen, Ger. Rumour has it that the new Earl’s primary interest will not be in the March after all. That he has not inherited Clifford, or the other two border castles. Nor has his brother Walter.’

Gervase paused, ale halfway between table and lips. Blood sang through his veins, a sudden bubble of warmth to lift his spirits.

‘If not Gilbert, then who?’

‘The Earl’s daughter. A girl from his second marriage. He married Petronilla de Clare a dozen years ago. So this daughter must be young—a mere child, I think.’

‘A child?’ Gervase tapped his fingers against the cup at the new slant on affairs.

‘That’s what my sources tell me. It might be in your interest after all to spy out the land.’ A sly smile on Hugh’s face, at odds with the ingenuous open stare.

‘It might. Well, now! Clifford in the hands of a child, a girl.’

Fitz Osbern sat and thought, staring down into his ale.

Clifford. The name had been engraved on his consciousness when a small child, written there in a forceful hand by his father. By rights the little border fortress was his, part of the Fitz Osbern estates. He knew it well, had once lived there for a short period when he was first wed to Matilda de Vaughan. Urgently, he pushed that unwelcome memory away to concentrate on what he recalled of the stronghold itself. For the most part a rough-and-ready, timber-and-earth construction, with only a token rebuilding in stone to provide basic living accommodation. But that was not important. What was, was that it held a strategic position on the River Wye, where the river could be forded, and was one of the original Fitz Osbern lands granted to his ancestor after the Conquest by the grateful Conqueror. It was undeniably part of his inheritance.

But then Clifford had been filched from his father, Henry, Lord Fitz Osbern, by the Earl of Salisbury when Lord Henry was campaigning in Anjou and he, Gervase, was holding court in his father’s name in Monmouth. All was done and dusted by the time his father returned, or before he could raise his own force and march to Clifford from Monmouth. By that time Salisbury was smirking from behind the walls.

And so Clifford had become a constant thorn in the Fitz Osbern flesh, of loss and humiliation that had worn his father down. Not in the best of health, he had seen it as a disgrace, a stain on his honour. A suppurating sword wound had carried him off to his grave only twelve months after. Gervase’s frown grew heavier. Any attempt by Gervase to recover the castles by force would have had Salisbury descending on him with the weight of a full battle force backed by all his Longspey wealth and influence, not to mention King Stephen’s ear.

But now Stephen was dead, so was Salisbury. And Clifford was owned by a child …

‘Does it mean so much to you?’ Hugh had watched the play of emotions over what he could see of his friend’s features. ‘It’s small, needs total refurbishment if you mean to keep a siege at bay. I doubt there’s been much rebuilding or improvement since the first wooden tower and earth ramparts were put into place. Does it matter so much that you reclaim Clifford?’

‘Oh, yes.’ There was no mistaking the light in Gervase’s eyes. The utter conviction in his voice. ‘It means everything.’

‘Because of your father.’

‘Because of him. And family honour, I suppose.’ A pause. ‘And because of Matilda …’

‘Ah, yes. I had forgotten …’

‘I hadn’t.’ Gervase’s hands clenched round the mug. ‘I’ll never forget. She died there, and I was not there to save her.’

The flat emotion in his face dissuaded Hugh from pursuing that line. He cleared his throat. ‘So what will you do?’

‘Tomorrow I ride for Clifford. I can hardly pass up so perfect an opportunity, now can I?’

‘No. Want company?’

Gervase searched the Marcher lord’s face. What better support could he ask for when planning a raid into hostile territory? A firm sword hand and a courageous spirit. A wealth of sound advice. Of recent years he had become used to acting on his own authority. Isolated, his mother said in moments of sharp honesty. Perhaps a friendly face at his shoulder would be welcome …

‘Well?’ Hugh prompted. ‘Do you want me or not?’

Gervase noticeably relaxed, nodded. ‘I do. If you have a mind to come and see me crow over my victory—then by all means.’

‘Let’s drink to it.’

With a combined force, on the following morning the two men took the road west out of Hereford toward Clifford. The day broke with a sharp wind and bright scudding cloud. The Black Mountains now came into sharp focus, rising out of the plain before them. Their objective, the small border fortress, stood on the south bank of the Wye to the north of the main ridge.

The company rode at ease in such familiar territory. Hugh stretched his limbs in the saddle, flexed his shoulders. He might appreciate town life—soft living, Gervase had called it—but it was good to ride in congenial company again. Conversation ranged wide, but gradually they circled to more personal matters. Hugh was quite prepared to take advantage of the long family association and touch on a sensitive nerve, the nerve he had neatly avoided the previous night. He knew Gervase would resist, but in the clear light of day broached the subject anyway.

‘You, Ger, need a wife.’

‘I know.’ The reply was level enough. ‘I could say the same for you.’

Ah! So that’s the game! Feint and parry to distract the opponent. De Mortimer decided to play along. ‘No, I do not. I was married for well over twenty years. I have two fine grown sons as heirs, now with young families of their own, to carry on my name and rule the Mortimer lands. I loved Joanna dearly. I do not want another wife at my time of life. I’m too set in my ways to start to conform to the demands and needs of another woman in my home. I like my own way too much.’

‘Not even to warm your bed on a cold night?’ Gervase slid a glance at the man who still carried himself with the vibrant energy of a younger man. The grey streaks, the fine lines beside eyes and mouth, were misleading.

‘There are other ways, if that’s what I choose. Such as a very personable merchant’s widow in Hereford who would like nothing more than to be a permanent addition to my bed if I raised my hand and smiled in her direction. So, no, I don’t see myself taking the oath again. But that’s side-stepping the issue—as you well know.’ His gaze sharpened and pinned Gervase, his advice becoming brutal. ‘Imagine me in the role of your late lamented father! You have no heir and you need one. You could be killed by a stray arrow or a well-aimed sword-cut today … tomorrow. You cannot burn the flame at the fair Matilda de Vaughan’s altar for ever. How long is it since she died? Five years now? Accept it, she’s lost to you. So you must turn your thoughts elsewhere. What are you going to do about it?’

The level voice acquired a distinct edge. ‘Find another, I suppose. Matilda, I should tell you, is not an issue. I doubt I’ll ever burn a flame for any woman.’ Gervase’s lips twisted in a wry smile. ‘Far too poetic for my liking. You sound like one of those damned troubadours, Hugh!’

Hugh barked a laugh. ‘When will you find another?’

‘When I have time.’

‘Any possibilities?’ Hugh persisted. ‘I suppose you have some preferences in the woman you will wed.’

‘Yes, of course I do.’ Gervase, obviously unwilling to spar with de Mortimer and determined to put an end to the discussion, rattled them off as if compiling a list of requirements for a battle campaign. ‘What any man of sense would choose. Well born, passably attractive, of course. Biddable, obedient, well tutored in domestic affairs, an efficient chatelaine who can hold the reins of my households—you know the sort of thing.’

Hugh hid a smile. He did indeed. The milk-sop sort of wife who would present no difficulties or challenges for Gervase. Who would not question or comment or contradict, but behave with perfect compliance. Soft and malleable as a goose-down cushion. And just as smothering and dull.

‘Had any offers lately?’ he asked innocently.

‘Not of late. Unless you count the de Longspey girl.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Salisbury offered me one of his family, to tie and hobble me into a neat alliance.’

‘Well, that surprises me.’ Hugh cast about in his mind for knowledge of de Longspey females. ‘Who was it?’

‘I’ve forgotten,’ Gervase admitted, annoyed at the tinge of heat in his face at this turn in the conversation. ‘I don’t think we were actually introduced. I was not interested and so refused.’

‘So you were rude and brutal.’

‘I was honest! What I was, as I recall, was grieving for my father’s death, and not willing to be bought off.’ He paused. Huffed a breath. ‘If you want the truth—then, no, I was not temperate. I have regretted it since.’

‘Was the lady not—ah, passably attractive, biddable, obedient, then?’

Gervase smiled, laughed with genuine humour. ‘I’ve no idea.’

‘I despair of you, Ger. But don’t leave it too long,’ was all de Mortimer could find to say.

‘As soon as I have this matter of Clifford settled, I’ll turn my mind to it.’

They worked their way around a particularly water-logged stretch of road, the horses’ hooves squelching in the heavy mud. The sun vanished and the rain began again.

‘What will you do if the child is already in residence at Clifford?’ Hugh suddenly asked on a thought.

‘I don’t expect it.’ Gervase’s brows rose. It had not crossed his mind. ‘Why would she? I would expect her to remain in Salisbury until she’s old enough to be wed. Clifford is no fit place for a child—and a girl.’

‘Probably not. But it might be so.’

‘Then I shall pack her back into her travelling wagon with her nurse, her clothes and her toys and her kitten or whatever she has brought with her—and send her back to her de Longspey brothers in Salisbury. What did you expect that I would do? Consign her to a dungeon?’

‘No, Gervase.’ A hint of censure, even of warning, touched the Marcher lord’s mouth for an instant. ‘I would expect you to treat her with all honour and courtesy.’

‘Don’t doubt it. I shall do exactly that.’

With the seed inadvertently planted by Hugh in his mind, Gervase found his thoughts returning to that disastrous interview with Salisbury, remembering primarily being overwhelmed with an anger that threatened to slip beyond his control. It made uncomfortable remembering. In retrospect, with his father just dead, he should never have done it. It had always been an impossible goal, but in his grief Gervase had made an attempt to regain his rightful property by an appeal to justice. Which Earl William had refused, but had then tried to buy him off with a de Longspey bride. No, he had not been as temperate as he might have been. As if he would ever accept a woman from the murderous de Longspey stable. He recalled storming out of the luxurious rooms in the Salisbury town house with barely a thought for the unfortunate girl who had been tricked out for his inspection. No, not the best of moves. And, worst of all, it had left Clifford securely in the hands of Salisbury. But no Fitz Osbern worth his salt would commit himself to living in Salisbury’s pocket as a dependent lord. It had pleased him mightily to fling the offer of a wife back in the Earl’s self-righteous face without a moment’s thought.

As for the girl … The lasting impression was one of—well, it was difficult to bring a complete picture to mind. He had barely registered her as other than a composed young woman with pale skin. A pallor that had warmed with bright colour along her cheekbones as he had bent his disdainful eye on her. Firm lips and a direct stare, more a challenge from an opposing knight than a soft glance from a well-born maiden. That was it. She had looked at him as if he did not come anywhere near to her high-vaunting standards as a husband. As if he was a marauding brigand just emerged from the Welsh mountains. Green eyes. Too direct, he recalled, too combative. Attractive, without doubt. But biddable, obedient? He would wager not. Nothing like Matilda. Not the sort of female he would ever want as a wife, whatever her breeding, whatever her connections.

As he left the audience chamber, failure rampaging through his blood, he had found himself standing close to her. She must have used lavender to wash her hair—the scent wound though his senses as she took a step back. And he had remembered, almost before it was too late, the courtesy with which he had been raised, and, digging deep through the fury, had enough nobility to make his farewell to her. He had kissed her hand. Why could he still experience that one moment with such amazing clarity? How the light texture of her fingers had for the briefest of moments cut through the anger in his head. Cool, smooth. Delicious skin like silk against his mouth. There had been that astonishing urge to kiss more.