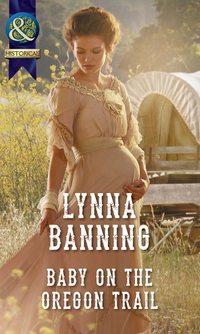

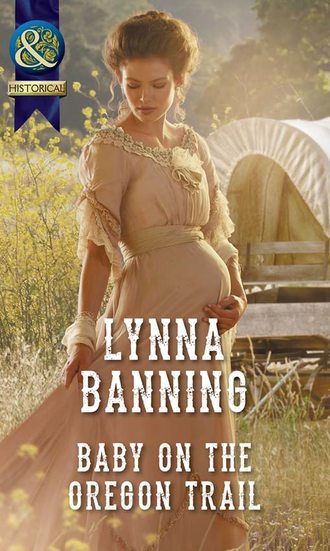

Baby On The Oregon Trail

Полная версия

Baby On The Oregon Trail

Жанр: приключениябоевики, остросюжетная литератураисторические любовные романывестернызарубежные приключениясовременная зарубежная литературакниги о приключениях

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу