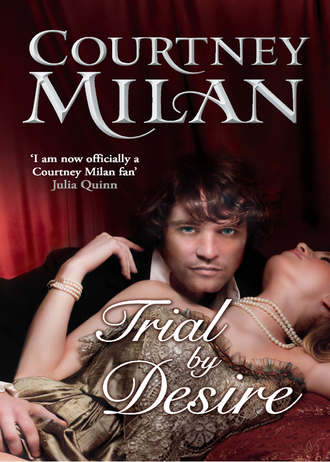

Полная версия

Trial by Desire

“Why isn’t he going?” She pitched her voice low, but even she could hear the desperation in her words.

Ned did not move his eyes from her. “I don’t know. I think he can smell the peppermints in my pocket. Here.”

He moved his hand slowly, slowly to his waistcoat pocket; then, just as agonizingly slowly, he pulled it away. His hand was close enough to brush her cheek.

He tossed another candy, throwing it far off into the grass.

She could not see the horse. She heard only its breathing. No tentative footfalls signaling its departure. Nothing. She could imagine Champion, warily scenting the wind, considering whether to put its back to its enemies.

Ned winked at Kate, and her toes curled.

“I don’t dare move,” she confessed.

“Really?” He gave her a naughty smile. “I can think of a dozen ways in which I might use that to my benefit.”

Kate swallowed. If she’d been reluctant to move before, his words rooted her in place now. Her half boots seemed to be made of thick iron. Her arms were bound at her side. Her mind filled with all the wicked things he might do to her. He might kiss her. He might run his hand down her side. He might undo those mother-of-pearl buttons at her neck and peel back the lace at her bodice.

He looked in her eyes. That old, heady desire swirled through her. A breeze eddied between their bodies, and she felt its caress as if it were his. His eyes narrowed, oh so subtly. He leaned forward.

Maybe this was why she had come here, danger or no danger, plan or no plan. She needed to assure herself that on some basic, primeval level, Edward Carhart still thought of her as his wife. To see if he would treat her as carefully, as gentlemanly, as before.

Champion moved away. Kate felt an elusive brush of wind against the nape of her neck, a wisp of air turning to nothing. Then, the clop of hooves.

“There,” Ned said. He had not dropped his gaze. Her lips tingled; her skin seemed too tight. He was going to kiss her. And foolishly, after three years of absence, she still wanted him to try. She wanted to believe he would attempt to revitalize their phantom marriage. She wanted to put her hands on the rough, wet fabric of his shirt, to feel the skin beneath. She wanted a taste of his carefree casualness, some indication that he thought of her as more than a delicate duke’s daughter. She wanted to believe he felt something for her, even if it was an emotion as evanescent and fleeting as desire. She bit her lip in an agony, waiting for him to move forward.

Instead he pulled away. “There,” he declared again. “Now you’re free to leave.”

Leave. She could leave? She stared at his profile in disbelief. After he’d practically pinned her to a fence post and joked he could use her twelve ways—after all that, he thought she could leave before he tried even one of them?

She bit her lip, hard. She could taste copper salt on her tongue. She could finally breathe now—and her breath seemed heated to fury.

“I can leave?“

He didn’t look back at her. His hands were balled at his sides.

“I can leave? And here I thought that was what you were best at.”

He flinched and looked back at her. “I was trying to be a gentleman.”

“I think,” Kate said, “you are the most obtuse man in all of Christendom.”

“Possible, but unlikely.” He gave her an apologetic shrug. “There are a great many Christians, and a good number of them are idiots. If there were not, Britain would never have gotten into a war with China over the importation of opium.”

She kicked at his boot—not hard, but enough to vent her frustration in physical form. “If I want to speak in hyperbole, I am going to do it. And don’t believe you can stop me with irrelevant political analysis. It’s neither sporting nor gentlemanly.”

“Trust me,” he said wryly, “right now, all I can think about is being a gentleman. It taxes my brain to think of anything except my gentlemanly duties.”

He swallowed and glanced down her neck. It was almost as if he’d never left, as if they were three months into their marriage. As if she were the one yearning forward, while he held himself back in polite denial.

“I retract my statement.” Her voice shook. “You are not the most obtuse man in all of Christendom.”

“No, no. You were perfectly right. The lady of the pasture always retains the right to hyperbole. Use it with my blessing.”

“There’s no need,” Kate said. “I’ve realized that I am the most obtuse woman.”

That finally brought his gaze flying from her bodice to her eyes.

She’d come out here to see if there was any substance to this marriage of theirs, to ascertain if he could accept a wife who took on unladylike pursuits. But she was still susceptible to him after all these years. And despite his informal attire, he still treated her as if he were the consummate gentleman.

“Here I am,” she continued, her voice still shaking, “practically begging you to kiss me. That you haven’t done so … well. I’m not so innocent that I miss the import of that. Men are creatures of lust, and if you haven’t given in to yours, you probably haven’t got any. At least not for me.”

His mouth dropped open.

“Just say so.” She looked up into his eyes. “Make this simple for both of us, if you will. Tell me you have no interest in me. Tell me, so I can stop standing in the middle of a field, believing you might kiss me. It’s been three years, Ned, and I am sick to death of waiting for you.”

He turned to her; his eyebrows drew down. He stared at her for a few seconds, and then he shook his head.

“Speak already.” She felt on the edge of desperation. “Tell me. What have you to fear? I can’t hurt you. And you can’t possibly hurt me more than you already have.”

“Women are the most curious creatures.” He reached out and caught a strand of her hair against her cheek.

That bare contact froze her. “Oh?”

“That’s what you think, is it? That I haven’t kissed you for lack of interest?”

“If you really wanted me, you wouldn’t be able to hold back. I understand how these things work.”

“Someone has been telling you lies. You must think all men are beasts by nature. That we see a thing, and like Champion, we charge unthinking across the field.”

He leaned toward her, and Kate moved back. The wood of the fence post pressed against her.

“You must think we have no semblance of control, that we can do nothing except obey our baser urges.”

That had rather been the import of the furtive discussions she’d conducted with her married friends. It was, after all, why men took mistresses—because they could not control their urges. So she’d been told.

“You’re half right,” he continued. “We are all beasts. And we do have base urges—deep, dark thoughts that you would shrink from, Kate, if you heard what they whispered. We have wants, and trust me, I want.“

She swallowed and looked up at him. He looked no different than before. He had that carefree, casual smile on his face, and for all that he loomed over her, his stance was easy. But she saw something in his expression—a tightening of his brow, the unbidden press of his lips—some quiet, unexplainable thing that suggested gray clouds lurked behind the casual sunrise of his smile.

“Right now,” Ned said, lifting a hand toward her, “I am thinking about taking you against that post.”

Her lungs contracted.

“Trust me when I say I am a beast.”

His fingers brushed down the rough lace at her neck. He found the line of her collarbone through the fabric. The gentleness of his touch belied the harshness of his tone; his hands were warm against her skin. He ran his finger down the seam of her bodice, down her ribs. The trail burned a line down her body. And then his palm cupped her waist and he pulled her closer. She tilted her head up to look in his face. His eyes were hot and unforgiving, and she could almost see the beast that he claimed he was reflected in them. And then his head dipped down—oh so slowly, so gently.

She might have escaped if she had simply turned her head. But she tasted the heat of his breath; she could still feel his words searing into her lips. I am thinking about taking you against that post.

In the back of her mind a voice called out in warning.

He would kiss her and be done; he might even have her against that post. It was his prerogative as her husband. And when he was done, he would walk away. As always, she would be the one left wanting upon his departure. She had to protect herself. She had to turn—

But she was already wanting, and it would serve nobody to send him away. And the truth was, women were beasts, too. She could feel the desire in her, crouched like some dark panther, ready to strike if he backed away.

He didn’t. Instead, his lips touched hers. They were gentle for only that first blessed second of searing contact. Then his hands came behind her and he lifted her up, pressing her against the post. His body imprinted itself against hers. His mouth opened, and he took the kiss she had so desperately wanted. His lips were not kind or polite or gentlemanly; his kiss was dark and deep and desperate, and Kate could have drowned in it. He tasted incongruously of peppermint. She gave back, because she wanted, and she had not stopped wanting.

She was not sure how long they kissed. It might have been a minute; it could have been an hour. But when he pulled his head away, she felt the sunshine on the back of her neck, heard a lark calling in some sad minor key from the faraway forest. Every nerve in her body had come to life; every sense was heightened.

“You see,” Ned said, “men are beasts. But the difference is, I control my beast. It doesn’t control me. Don’t think my control means anything other than … my control. Because right now the beast wants. It wants to ravage you, out here in the open where anyone can see. It wants to take you, and it will be damned if you’re not ready.”

“I’ve always been ready.” She heard the confession slip from her mouth, so clear and crystalline.

“Really?” His tone was dry. “‘I think our marriage might dry up and blow away,’” he paraphrased at her, “‘with one good gust of wind.’ Kate, you don’t even trust me. I would be a monster if I came back after a three-year absence and expected everything to resume, just like that.”

“You don’t need trust to consummate a marriage, Ned.” She shook her head. “I am nothing if not practical.” But her heart was beating in impractical little thumps.

“Would you tell me why Harcroft made you so uneasy today? I know he can sometimes be a bit exacting, a bit too perfect. But I’ve known him since the two of us were in short pants. He means well. He was—is a friend of mine, you know.”

Everyone thought Harcroft meant well. It was the hell of the situation, that anyone she told would run to Harcroft, seeking confirmation of her tale. The man seemed reasonable. Nobody would give credence to a week-old collection of bruises, not when Harcroft explained them away so capably. And besides, she’d promised Louisa to keep silent.

As for Kate’s own wants and desires—the substance of her marriage, the yearning of her flesh for his—set on the scale opposite Louisa’s life, they balanced to nothing.

Ned thought Harcroft meant well. They had been not only friends, but good friends. When Ned had asked, Harcroft had welcomed Lady Blakely into society despite her lack of provenance. His support had made the difference between a grudging acceptance and a complete denial.

He had smoothed over a situation that might otherwise have proven difficult. They all owed Harcroft. Nobody even asked whether Louisa might have been prudent to run away.

She backed away, but the post prevented her retreat. “No. You’re right. I don’t trust you, yet. If you had left your new wife to the depredations of the ton, exposed her to jokes and uncouth wagers, would you trust yourself?”

“Kate, I—”

She set her hands against his chest and shoved. She had hoped he would stagger away; instead, he moved back, gracefully, as if her push had been nothing more than a gentle reminder.

He scrubbed one hand through his drying hair, which had fallen into his eyes again. “I left England to prove something to myself. I suppose … I suppose I still have a great deal to prove to you.” He said it in a tone of surprise, as if he were somehow just discovering he had a wife and responsibilities.

Hardly reassuring. He hadn’t needed a reminder of what he owed Harcroft.

CHAPTER SIX

NED’S DAY HAD NOT improved. Supper conversation had been blighted; nobody had wanted to act as if this were a typical house party, where the men would consume a quantity of port before meeting the women for a companionable game of charades. Bare civility, it seemed, was charade enough.

Instead, after the evening meal, Ned’s houseguests had disappeared, and Ned had made his own way to the library. He’d gone there because the room seemed safe—an empty cavern of bookshelves and shadowed furniture, lit only by a lamp on a low table and the orange light of a fire.

But as he stepped inside, he realized he wasn’t alone.

“Carhart.”

Ned heard the deep voice before he made out the dark silhouette slouching in a chair before the fire. The boughs had burned almost to coal; only a dim glow came from the grate. A glass of port, filled knuckle-high, sat on a little table beside Harcroft. Knowing the man, he’d likely scarcely touched it.

“Come,” Harcroft said. “Join me in a glass.”

Not a chance. His lip curled in awkward distaste.

Even though Ned hadn’t said a word, Harcroft must have caught his meaning. The man swiveled in his chair to look Ned in the eyes. The look they exchanged was rooted in a years-old memory, dredged from their respective youths. They’d both been at Cambridge. One evening they’d shared one too many bottles of claret. It had been during one of Ned’s bad periods—just before he was sent down for sheer listlessness. The spirits he’d imbibed that night hadn’t cured whatever it was that ailed him. Instead, on that evening, he and Harcroft had ended up getting bloody drunk.

After what Ned was sure was only the fourth bottle of wine, and Harcroft insisted was the sixth, they’d engaged in an activity that no self-respecting men would ever admit to—they had talked about their feelings.

At length.

Ned still got the shivers just thinking about that night.

“A very tiny glass,” he said, holding up his fingers. “Just to hold.”

“Just so.” Harcroft’s lip quirked in understanding—and possibly in memory. He stood and walked to the decanter on the sideboard and poured Ned the barest slug of tawny liquid.

Ned took the glass and seated himself in the chair opposite Harcroft. They stared into the fire.

It was easier than looking Harcroft in the eye. Even drunk, they’d instinctively avoided direct discussion of any topics so squishy and laden with emotion as the ones that had most bothered Ned. But aside from the Marchioness of Blakely, Harcroft was the only person who knew even a hint about what ailed Ned.

That night, he’d made his veiled, maudlin confession. He had told Harcroft that he feared there was something wrong with him, something irretrievably different. Harcroft, who had been similarly drunk, had admitted the same was true for him. They’d talked around the issue, of course; even soused, Ned was not so stupid as to complain about a bewildering and inexplicable sadness that sometimes came over him. Harcroft, too, hadn’t described what happened. Instead, they’d called it a thing, an accident. That night, it had seemed a separate beast. They had drunk to its demise.

Drinking hadn’t killed it.

Instead, Ned remembered the conversation as a dim, drunken mistake. Mutual confession hadn’t brought them closer; instead, Ned had wanted to scrub all memory of that conversation from his mind. Harcroft had been a good friend, before; after, Ned had wanted to stay very, very far from the man, as if he had been the source of contagion. As if speaking about the thing that afflicted him had somehow made it more real.

The fire crackled in front of them, and Ned shook his head.

“What was it like?” Harcroft fingered his glass of port. If he’d done more than wet his lips tonight, the level of liquid in the glass didn’t show it. Since the evening of the mawkish confessions, Harcroft, too, had scarcely touched spirits. He’d barely sipped his wedding toast.

“What was what like?” Ned asked uneasily.

“China.”

A safe enough topic. So it might have seemed, were Ned’s journey not so inextricably bound with the subject of their conversation on that night. He set his own glass aside and shut his eyes. Images flashed through his head—high green hills rising steeply out of the clear blue glass of the ocean, vegetation choking every inch of land; humid heat and the overpowering stench of human waste; the glint of water off polished steel, the sun hot overhead; and then, once he’d left Hong Kong, the delta of the Pearl River, obscured by the acrid smoke of cannon fire.

This evening, Ned had no desire to delve into those feelings. Not at any length at all.

Hot was finally the word Ned settled upon. “So hot you sweat buckets, and so damned humid those buckets never evaporate. I was wringing sweat from my coat half the time.”

“Ha. Sounds uncivilized.” Harcroft stretched out and hooked his feet on another chair, pulling it closer to use as a footrest. The fire snapped again, and a small draft brought the smell of woodsmoke to Ned. The faint scent seemed an echo of those sulfurous clouds of gunpowder in Ned’s memory.

“If civilization is waltzes and twelve-piece orchestras playing in gilt-edged drawing rooms, then, yes. It was uncivilized.” With his eyes still closed, Ned could feel the soft swell of water rising underneath his feet. A small smile played across his lips.

“What else might civilization be?” Harcroft’s voice was amused.

In Ned’s mind, a ragged breath of low mist obscured the mouth of the river—no mere cloud of water vapor, but smoke, acrid and sulfurous. Shredded remnants of cannon fire.

“I think we carry our civilization inside us,” Ned said carefully. “And our savagery. I suspect it takes very little for anyone to switch from one to the other. Whether you happen to be British or Chinese.”

“Blasphemy,” Harcroft said with very little heat. “Treason, at least.”

“Truth.” Ned opened his eyes and glanced at Harcroft.

The man had folded his hands around his glass. He stared into the liquid, as if he could discern all civilization in its golden depths. When he finally spoke, his voice was low. “Is your savagery so close to the surface, then?”

This was coming rather too close to that drunken conversation.

As for savagery … Before he’d trekked halfway round the world, the word savage had connoted all kinds of strange and different things: cannibalism and half-clothed women. After, he thought more of Captain Adams. Or that acrid bank of mist, rising over rubble. Or the dens where the opium-eaters retreated, to escape a world they did not dare remember.

“My savagery?” Ned asked. “That’s rather the wrong word for it.” Savagery also entailed action, and for Ned, the dark times that visited him were quite the opposite of action. He’d never wanted to eat anyone’s flesh or murder anyone’s mother. At his very worst, what he’d wanted more than anything was simply to … stop. Sometimes he still wanted to stop; the only difference was, now he’d learned not to.

Ned blinked, and the firelight caught his port, the light glinting off it like steel, flashing the hot sun against water.

Harcroft simply stared into the fire. “It’s not savagery to teach someone a lesson. To show someone his rightful place in the world. Sometimes you need a show of strength to demonstrate that rules are not to be trifled with. You may call desire for order and dominance in yourself savagery, but we both know the truth. It’s the way of the world.”

“But one can go too far,” Ned interjected. “We’re the ones who continue to insist on our right to poison the Chinese with opium. We’ve killed women and children. One doesn’t need to commit savagery to show strength.”

“Sometimes these things happen by … by accident.” There was something strangely earnest about Harcroft’s tone, and he looked away, an oddly rigid set to his jaw.

“You call those things accidents?”

“Sometimes, you know—I suppose I can understand how it all starts. The beast just grabs you by the throat, and before you know it … “ Harcroft looked up and met Ned’s eyes. “Well. You know.”

Ned did know—at least, he knew how it happened for himself. But he had learned how to control his responses, how to pretend that he was like everyone else. But then, neither of them was soused enough to tell the full truth, and so Ned had no idea what Harcroft meant.

“I know that you need to be ready,” Ned said. “You need to be stronger, better than it, so that the next time it reaches out with cold fingers, you are faster than it, and it can’t touch you.”

Harcroft looked into Ned’s eyes for a very long time. Finally he looked away. “Yes,” he said. “That’s it. Of course.” The wood on the fire crackled, and a log fell. Sparks flew up.

“As we’re done talking about China, how do you find England, by comparison?”

Gray. Rainy. Even the birds sounded different. He had come home, but every aspect of that home had been rendered foreign in his absence. Even his wife. Especially his wife.

“I find England cold,” Ned finally said. “Damnably cold.”

THE NIGHT HAD BECOME even colder by the time Ned waved his valet away. After the servants left, he carefully snuffed the fire they’d started in the grate. He didn’t want the warmth. The chill kept his mind sharp.

Only a single candle on a chest of drawers cast a little light. Now yellow light fell on the door that connected his room to the room where his wife slept. Without asking, the servants had put him up in the master’s quarters; even the architecture seemed to think a marital visit was a foregone conclusion.

Any other man would not have needed to think any farther than that. Kate was his wife; and she was willing—if grudgingly so. She was also damnably arousing. There was no reason not to take her, then—no reason that would have signified for any other man.

Ned set his jaw and walked to the connecting door. He had been expecting a rusty squeak—some resistance to signify that this door had remained closed for years. But it opened easily. Some servant with no sense of the symbolic had kept the hinges well-oiled during the years of his absence, as if their marital life had merely been cast into temporary abeyance.

Her curtains were pulled back, and the moon cast a shimmery light along the floor, highlighting a path that led to her bed. Her seated silhouette was outlined in silvered clarity. Her slender limbs were drawn up in front of her; her arms were clasped about her knees. He could see the delicate arch of her foot, peeking out from underneath a white chemise.

She turned abruptly at the sound of the door. “My God, Ned. You nearly scared me out of my skin.”

Aside from that long fall of muslin, it appeared that skin was essentially all she was wearing. His mouth dried.

It had been a long time. And damn, he wanted her. He wanted to claim the curves that lay under that fabric. He wanted to cross the room in one bound and press her against the feather tick. Desire coursed through him, pounding in his ears as powerfully as a flooding river, pulling all his good intentions downstream.

She pushed her legs out in front of her, exposing a smooth curve from foot to calf. Her feet flexed, pointed, and then she stood in one graceful movement. The moonlight rendered the white stuff of her shift translucent. He could see the curve of her waist through that thin fabric. His hands yearned to touch her.