Полная версия

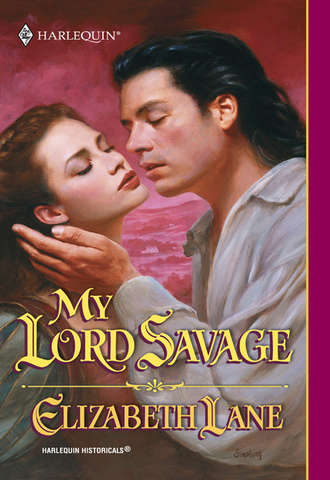

My Lord Savage

“Father!” Rowena seized his arm, gripping it so hard that the old man winced. “I beseech you in the name of humanity, don’t do this!”

“And what would you have me do instead?” Sir Christopher thrust her away from him, scowling at her over the top of his thick spectacles. “Should I let him go? Should I turn the poor devil loose to roam the countryside like a mad dog and probably end up being shot or hanged?”

Rowena exhaled slowly, knowing she had no counter to his question. “Very well, then, get me the keys to his manacles. If the man is going to live here, the least we can do is give him a good washing and some proper clothes.” She wheeled away from her father and took two strides toward the defiant prisoner.

He did not move, but the blistering rage in his black eyes stopped her like a wall. Rowena hesitated. Her hand crept to her throat as she glimpsed something else beneath that rage—a sorrow so deep and so desperate that it tore at her heart.

“No closer,” her father cautioned her from behind. “The creature is dangerous. Given his freedom, there’s no imagining what he might do, especially to a woman. You’re to keep a safe distance from him, Rowena, at all times.”

Rowena studied the prisoner across the span of a few paces. Dangerous? Yes, certainly. He was a wounded animal, maddened by pain and fear. But what if she were to reach out and touch him in gentleness, in compassion?

Her hand stirred, but even that slight motion ignited a fresh blaze of hatred in the man’s eyes. Rowena felt as if she had stepped too close to a fire and been singed from head to foot by a sudden flare.

Before she could gather her wits, her father spoke gruffly to the two servants. “Take him to the cellar and lock him into the barred room. You’ll find the key hanging on the wall behind the door. Leave him a little water and a slop bucket—pray that after two months at sea the wretch will know what to do with it.”

“How can you just shut him down there in the dark?” Rowena had found her tongue and was determined to speak. “Look at the poor creature! He needs food and warm clothing! He needs some measure of kindness in this strange place!”

“All that he will get soon enough!” Sir Christopher retorted. “But first, as with any wild beast, we must break that proud spirit of his. Only after he has learned dependence on his masters will he be docile enough to study.”

“Father, there are rats down there, and heaven only knows what else—”

“Hush, Rowena! My mind is made up! We can talk at supper.” Sir Christopher turned away from his daughter and unleashed his irritation on the servants. “What are you staring at? Get him downstairs—and watch him, mind you. I was told that the creature is uncommonly treacherous!”

The two husky Cornishmen tightened their grip on the prisoner’s arms and began dragging him toward the back door of the house. Until that moment the man had not made a sound, but as the three of them reached the stoop, he suddenly threw back his head and uttered a shattering cry—a sound so savage and primitive that it raised the fine hairs on the back of Rowena’s neck and startled a flock of jackdaws perched on the edge of the roof. The cry was not born of fear or pain—that much Rowena knew at once. No, her instincts told her, it was a warrior’s battle scream, an outburst of sheer, defiant rage.

Startled, the two servants drew back for an instant, and suddenly the dark stranger was free. He lunged across the courtyard, dragging the weight of his shackles as if they’d been made of twine. In full health, he might have made his escape, but as it was he tired swiftly. Halfway between the house and the stable, Thomas and Dickon caught up with him. A swift kick from Thomas’s boot sent the prisoner sprawling facedown in the muck. From there it was an easy matter for the two men to seize his arms and jerk him to his feet once more.

Dripping mud and manure, the savage faced his captors. Then, to everyone’s astonishment, he burst into a sudden stream of the vilest profanity known to any English sailor.

“…Son of a whoring bitch…filthy, murdering red-skinned bastard…” The phrases he spat purpled the air around him. He had learned them on the voyage from America, Rowena realized, sick with dismay. In all likelihood, they were the only English expressions he knew.

A bitter smile tugged at the corners of Sir Christopher’s mouth. “Well, well,” he said, nodding in satisfaction. “At least we know the creature is capable of learning human speech. Take him to the cellar.”

Rowena half expected the savage to strike out again, but he had exhausted his strength for the moment. He offered no more resistance as Dickon and Thomas gripped his arms and dragged him into the house.

Black Otter felt as if the great lodge had swallowed him whole, as a giant frog might swallow a fly.

His gaze darted furtively over whitewashed walls and ceilings higher than a man’s reach, over huge, ornate pictures made entirely of thread, over tables and chairs that looked as solid as the trunks of great trees. At first he had planned to memorize the way inside so he might know it when the time came for his escape. But he had long since given up. The place was a maze of corridors and chambers as complex as the inside of a termite nest. Surely, with such a lodge, the old man who had taken him from the ship must be the chief of all the white tribe.

One of the rooms he had passed through appeared to be used for nothing but cooking. The fire pit was built into one wall like a cave, and over the crackling flames, the carcass of a large animal hung roasting on a metal spit. Loaves of fresh brown bread lay on long tables. Black Otter had never seen so much food in one place. The mouthwatering aromas had made his stomach contract with hunger, but no one had offered him food or even a sip of water. He had been dragged through one immense room after another and, at last, down a long, narrow passageway that ended in a pool of darkness.

A third man, plump and pale, joined them now. He was carrying a torch made of twisted reeds dipped in pitch. The foul smoke stung Black Otter’s eyes and nostrils as they forced him downward into the black space that opened up before them. His moccasin-clad feet stumbled on the rough stone steps.

Fear closed around his heart as the clammy air, redolent with mold, filled his lungs. It was cold and damp down here, below the earth. And without the torch it would be darker than the belly of the great boat. Even if they did not kill him at once, he would die slowly in this place. He would die like a caged animal, from want of sun, air, warmth and freedom. And he would never know what had happened to his precious children.

Torchlight flickered over mildewed stone walls, then over moldering crates and barrels that looked as if they had not seen daylight in years. Black Otter heard the faint drip of water and the scurrying sound of rats.

One of the men spoke as the torchlight came to rest on a framework of rusty iron bars. A door creaked open on corroded hinges, revealing a tiny, cavelike room that looked as if it had been hacked from the living flesh of the earth. Realizing he was about to be shoved inside the terrible place, Black Otter began to struggle—a waste of strength. With a quickness that belied his size, the largest of the white men struck out with one meaty fist. Black Otter saw the blow coming, but he was powerless to dodge or counter. He felt a flash of pain as the massive knuckles crunched against his cheekbone. Then the torchlight exploded into swirling stars, and he pitched forward into darkness.

Rowena toyed with her supper, too agitated to eat. “I understand none of this!” she declared, pushing her plate to one side. “You say you paid a hundred fifty pounds for the man! A small fortune, Father, and far more than we can spare! What under heaven possessed you to do such a thing?”

Sir Christopher lifted his tankard and took a draught of ale to wash his mouth free of bread and meat. “My dear Rowena,” he answered, scowling, “I grant you, a hundred fifty pounds is a considerable sum, but you must look on it as an investment.”

“An investment?” Rowena glared at him.

“An investment in the future. Mine and your own.” He leaned forward across the long, bare table where the two of them sat. A single candle sputtered between them, etching his face with stark ridges of light and shadow. He looked old and tired.

“Listen to me, child.” His earnestness all but made her weep. “We both know my reputation as a scholar has faded over the years. I am no longer consulted by the queen or invited to lecture at Oxford. But with the new discoveries I hope to make, all that will change.”

“You talk in riddles! What new discoveries?” Rowena asked, her concern deepening. Had the great Sir Christopher slipped over the edge of reason?

“Think of it, Rowena!” The candle flame, reflecting in his spectacles, transformed his pale eyes into blazing lights. “Spain has already gained a solid foothold in the Indies. While there is time, England must seize her own piece of this bright new world. The vast country to the northwest, rich in furs and land and treasure, is ours for the taking, save one obstacle—the savages who live there!”

Rowena gazed at her father, excitement clashing with dismay. The Spanish conquistadores had long since subdued the more civilized tribes of tropical America—the Aztecs, the Mayans and, far to the south, the Incas. But the northern forest dwellers were savage brutes, rumored to be more beast than human. Their ferocity had long kept white invaders from their shores.

And now one of them was here in England, locked in the cellar of this very house.

“Think, Rowena!” Sir Christopher’s voice rasped with emotion. “Think what we might learn if we can communicate with the creature—if we can subdue him, teach him to speak, perhaps even press him to serve as a guide and interpreter!”

“He’ll serve as nothing if he dies of the cold and damp in the cellar,” Rowena snapped. “A hundred fifty pounds, indeed! You might as well have—”

Her words died in a little choking sound. She stared at her father, thunderstruck. “By my faith, you didn’t just happen across that poor wretch in Falmouth, did you? You planned this, all of it!”

“Hear me out, Rowena.” Sir Christopher could be as strong-willed as his daughter. “What I did, I did for my own good reasons.”

“How long did it take you to arrange it?” she demanded, trembling as she rose to her feet. “Six months? A year? What did you have to do to get him?”

“I put up printed notices in the taverns around the docks,” he answered with the cold stubbornness of a rock in the Narrow Seas. “The notices declared that I would pay one hundred fifty pounds for a healthy savage from North America. A messenger brought me word yesterday that a captain, newly arrived, had such a specimen—”

“A captain, indeed! A privateer, you mean! No better than a pirate!”

“In truth, I did not think to ask.” Sir Christopher had marshaled his defenses now. The set of his shoulders and the jut of his jaw declared that he had taken his position and would not be moved.

“And not a word to your own daughter!” Rowena fumed. “Indeed, why did you neglect to make me privy to your plans?”

Sir Christopher speared a morsel of beef with the point of his knife and used it to jab the air emphatically as he spoke. “Because you would have behaved exactly as you’re behaving now. And you would not have succeeded in changing my mind, Rowena. Not by a whit. The discoveries I make about this creature and his world will restore my favor with the queen. Yours, too. Perhaps you might even be offered a position at court—”

“I have no wish to wait upon the queen, Father. My life is here in this house with you.”

Sir Christopher sagged in his chair, an expression of profound sadness stealing over his once-vigorous features. “And what kind of life have I given you, child? When I pass on, you’ll be alone here. No husband, no children—”

“Let the savage go,” Rowena demanded gently. “Take him back to Falmouth and put him on a ship for the New World. I’ll pay his passage myself out of the dowry of jewels my mother left me.”

Rowena’s father shook his head. “You know as well as I do he would never survive the journey. Likely as not, the captain would take your money and throw your savage overboard at the first sign of trouble.”

“My savage?” A bitter smile tugged at the corners of Rowena’s mouth. “So now he’s my savage, is he?”

“Why not, since you seem to have taken up his cause?” Sir Christopher scowled at the tidbit of meat on the end of his knife, then brought it to his mouth and began the tedious chewing that his meager teeth allowed.

“Well, then, as long as I have claim to him, I want him out of the cellar,” Rowena said. “There are empty chambers aplenty in this house. The least we can do is lock him in a warm, dry place with ample food and bedding.”

Sir Christopher downed the remains of the meat with a swig of ale. “What? And have him leap out of a window or attack the first poor soul who comes in to feed him? No, Rowena, as long as the creature is a danger to himself and to others he will remain behind bars. As for you, you are not to go near him, nor is any other woman in this house. Leave the tending of him to Thomas and Dickon.” He pushed back from the table, his chair scraping on the stones. “And leave the breaking of him to me. I mean it.”

“Breaking?” Rowena paused in clearing away the platters, something she often did if the evening meal lingered past the time for the servants to retire. “You talk about him as if he were a wild animal!”

“That is precisely what he is.” Sir Christopher rose wearily to his feet. “I wasn’t always the doddering old fool you see before you, my dear. Just give me a little time. Believe me, I know how to break a beast—and a man.”

Black Otter gripped the iron bars, his eyes straining to see into the murky darkness that lay beyond his cell. The effort was useless. For all he could make out, he might as well have been blind.

How long would they keep him here? Time lost all meaning when the sun was gone. At least, in the belly of the great boat, he had caught occasional glimpses of light from above. He had been able to hear men moving and shouting on the decks overhead and, in time, had learned to tell day from night by the sounds they made.

Here there was nothing but darkness and bone-chilling cold. Nothing but the scurry of rats and the faint, distant drip of water. Nothing but his own burning rage to keep him from giving in to madness.

He thought of the two husky men who had dragged him through the great lodge and down the dark stairs. He pictured the pale, plump man with the torch and the old one, the chief of all the white men. He remembered the woman, tall, like a man, but with a disturbing grace about her, the skirt of her odd costume flaring around her legs like the inverted cup of a huge, dark flower. One by one he focused his anger on them, letting it burn hot in the cold darkness. Even her. Even the woman. He hated them all.

But anger would not get him out of this place, Black Otter reminded himself. For that he would need a cool head and the cunning of a fox.

He had explored his small prison from top to bottom, fingers probing the straw, the walls, the fastenings that anchored the heavy barred door. The enclosure was solid stone, with not so much as a niche that could be widened into an opening. The bars, as well, were too strong to bend and too closely spaced for even a child to squeeze through. His only chance of escape lay in seizing the instant when one of his captors opened the door. For that he would need to be on constant watch.

The iron manacles ground into his scab-encrusted wrists and ankles, raising an ooze of fresh blood as he moved into a shadowed corner and eased himself into a low crouch against the wall. He had found the water jar earlier and taken a cautious sip. It was fresh and cool, and after the foul stuff he’d been given on the boat, it had taken all his willpower to keep from gulping it to the last drop. Even now, his parched throat cried out for more. But he could not surrender to thirst. There was no way of knowing how long the water might have to last.

With a broken exhalation, he leaned back against the wall, closed his eyes and tried to rest. To take his mind off the pain of his battered body, he thought about Lenapehoken, his homeland, with its deep forests and clear-running streams; and he thought about his children. He pictured Swift Arrow bounding toward him along a mossy forest trail, his small brown face split by a reckless grin. He imagined Singing Bird kneeling beside the fire, her gaze lowered, her young features—awkwardly balanced but holding the promise of beauty—soft in the golden light. He would return to them, he vowed. Whatever the cost, if they lived he would find them. He would gather them into his arms and the three of them would be a family once more.

Whatever the cost….

Rowena lay on her bed, her hair spread in a wild tangle on the pillow. Above her the midnight moon glimmered through the leaded windowpanes. She had been tossing for hours, it seemed, turning this way and that, willing herself to sleep. But it was no use. Her body was tired but her churning mind would not grant her release.

Frustrated, she sat up, swung her legs over the edge of the bed and brushed her sweat-dampened hair back from her face. Her chamber, closed as always against the night vapors, was warm and stuffy. Rowena hesitated, then rose and strode to the window. Vapors be damned! She needed fresh air!

Flinging open the sash, she stretched on tiptoe and let the sea wind wash her face and body. She was naked beneath her shift, and the coolness through the soft, damp linen was as poignant as a caress. The curve of the crescent moon gleamed like a Saracen’s blade in the dark sky. Waves crashed and murmured against the rocks at the foot of the cliff.

Rowena’s thoughts returned once more to the savage, her savage, locked away from light and warmth and air. She remembered his eyes, the anguish she had glimpsed beneath the glaze of hatred.

What torments was he suffering down there alone in the darkness? Was he hungry? Injured? Even dying? Could she make the prudent choice and harden her heart against his need?

Or was it already too late?

Trembling, she closed the window and fastened the latch. Almost without willing it, she found herself moving to the wardrobe, slipping her light woolen dressing gown off its hook on the door. A voice in the back of her mind shrilled that she was setting out on a madwoman’s errand, risking her father’s anger and her own safety. Rowena paid it no heed. How could she rest in her soft, warm bed when a fellow being was suffering under her very roof?

Resolutely now, she gathered a wool-stuffed quilt from the foot of her bed. Then she glided across the room and opened the door into the hallway. Sir Christopher would scold her, to be sure. But she would face that unpleasantness tomorrow.

The house was dark but Rowena’s bare feet knew every knot in the cool wooden floor, every step of the long staircase that curved down into the great hall. The rushes whispered beneath her soles as she skirted the table and hurried to the kitchen. The upper floors of the house she knew by heart, but not the cellar, whose darkness was like the wet black pit of a mine. She would need a light to find her way.

Groping amid the clutter, she found a candle and lit it with a coal from the fireplace. The light glowed eerily in the cavernous kitchen, flickering over soot-blackened iron pots, shelves, cupboards and long tables. Rowena found a loaf of bread in the pantry and tucked it under her arm with the quilt. Much as she loved her father, she could not condone his plan to starve the savage into submission. Not after glimpsing the pain in those proud, black eyes.

As she made her way down the rough stone stairway, a mouse scurried across her bare foot. Rowena’s lips parted in an involuntary gasp. If only she’d thought to wear her slippers—

But there could be no going back now. If she returned to her room for the shoes, her courage would surely fail. She would shut herself in, draw the bed curtains and spend the rest of the night hidden beneath the coverlet, quaking like the coward she was.

For as long as she could remember, Rowena had harbored an unspoken terror of the cellar. Perchance something about the place had frightened her when she was too young to remember; or one of the maids had told her horrible stories to keep her from toddling down the dark stairs. Whatever the reason, her skin crawled as she descended the long passageway. She cupped a protecting hand around the candle flame, fearful that some stray draught might blow it out.

At the center of her fear lay the barred room. In Rowena’s lifetime it had been used only for storage. But it was well known that the long-ago Thornhill who’d built the great house had used it for a very different purpose. People had died in that room.

Past generations of the Thornhill family had shown a penchant for barbarism, Rowena reflected. But not Sir Christopher. Not, at least, until today. Had the dark trait surfaced at last in her own gentle father?

The damp cellar air rose around her like a miasma, smelling of mold and rot. She thought of the savage huddled alone in the darkness. Was he frightened? Angry? Would he understand that she had come to him in the spirit of kindness?

Rowena tried to imagine how he had been captured, chained and taken from his home. A man such as he would have fought like the very devil. Why hadn’t the ship’s crewmen captured someone more docile? A woman, or even a child?

The answer to her question came at once. The privateers had wanted their captive to reach England alive. They had chosen a strong man—a warrior—because he would have the best chance of surviving the miserable voyage.

Darkness, as cold and heavy as the body of a snake, pressed around her as she reached the bottom of the stairway. The candle seemed little more than a sputtering pinpoint. She inched forward, protecting the tiny flame. By its dim light she could make out a jumble of stacked boxes and barrels and, beyond them, the stark outline of iron bars.

Rowena paused, holding her breath and listening. She could hear the faint drip of water from an underground spring and a low rustling noise that could have been a rat. But even in the stillness, she heard no sound at all from the barred room.

She crept closer, the candle thrust ahead of her. Now she could see the bars clearly. She could see into the cell beyond them, all the way to the far wall.

No one was there.

Forgetting caution, she hurried forward. Had the savage escaped? Had he died on the way to his dark prison? Or had her father simply decided to put him somewhere else?

Rowena reached the bars and pressed against them, raising the candle to see into the far corners of the small room. Only then did she notice the straw piled in the shadows—a long, bumpy mound of it, the size and shape of a man’s body.

Relief swept over her as she lowered the light. Cold and weary, the savage had taken the only sensible course of action. He had burrowed into the straw like a wild animal and gone to sleep.

Rowena’s breath hissed out in a jerky release. Her errand of mercy would be easier now. She had only to push the bread and the quilt between the bars and go. When he awakened the savage would discover her gift, and if he was as intelligent as he appeared to be, he would understand that even among the English there was compassion.

Dropping to a crouch, she set the candlestick on the stone floor to free her hands. She was about to push the bread between the bars when a rustle in the shadows reminded her of the rats. An unguarded loaf would only serve as bait for the horrid creatures, drawing them by the score into the cell. The bread would be gone before the captive could wake up and drive them off.

Rowena hesitated, torn. She could call out and rouse him. But that in itself would be a heartless act. Sleep was the only blessing left to the wretched man. If, perchance, he was dreaming of his homeland and loved ones, why awaken him to misery?