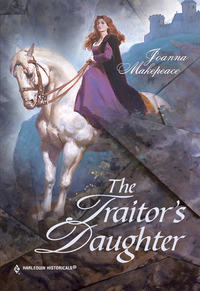

Полная версия

The Traitor's Daughter

Since Peter was engaged in mounting his lady upon her palfrey and David was still about his business in the inn, Sir Rhys lifted Philippa once more into the saddle.

“These merchant’s clothes form an excellent disguise, and were well chosen,” he remarked as he fingered the wool of her russet gown.

Angrily she flashed back at him, “These garments are no disguise, sir. We live in virtual penuary at Malines while you live in luxury on my father’s estates.”

He looked from the tip of her proudly held young head to her little booted foot resting in the stirrup. How very lovely she was, even dressed, as she was, in these dull, outmoded clothes. Her golden curls peeped provocatively from beneath her simple linen coif, for she had thrown back the hood of her travelling cloak.

He had said earlier that she possessed the same golden loveliness of her mother, but in Philippa now that beauty was enhanced by vibrant youth. Her skin glowed with health and her green-blue eyes, almost turquoise in the sunlight, sparked with angry vitality. There was a seeming childlike fragility about her in her exquisite petiteness, which he had noted when he had come to her rescue in that darkened courtyard. It had brought out a protective tenderness in him, yet now his pulses raced as he thought how much of a true woman she was. He sensed the intensity of her bitterness towards him, read it in the set of her little pointed chin, in that hauntingly elfish, heart-shaped face, in the hard-held line of her lips, despite their sensuous fullness, which now he longed to lean forward and kiss.

He had met and known many women at court, and other, more earthy voluptuous beauties who had lived on his estates and granted him favours, daughters of his tenants and servants, but none had stirred him as this woman did.

When Philippa had risen, trembling, from her attacker and he had felt her quivering fearful young body pressed against his heart, he had recognised the inner strength of her, the courageous determination to recover quickly so that she could rush to her mother to warn and protect her, her genuine concern for their squire, even under the stress of her own ordeal.

She was in fighting form now, and amused admiration for her warred within him with the sudden surge of desire which ran through him.

He chuckled inwardly. She would need to be managed—for her own safety and that of those she might imperil if she gave way to rashness brought on by her own contempt for him.

“Ah,” he murmured, his dark eyes flashing in understanding, “so that is the rub, Lady Philippa, and the direct cause of your suddenly adopted hatred for me. Your man has informed you about my estates and how my father obtained them.

“I hate no one, sir,” she said coldly. “That would be against the teaching of Holy Church. Contempt would be nearer the mark to explain my feelings towards you.”

“You think I should have refused to accept my inheritance?” He gave a little dry laugh. “I would have thought you would have gained a better knowledge of the ways of the world than that, Lady Philippa. I am quite sure your father’s many services to the late King won him the preferment he both desired and earned.”

She went white to the lips and, seeing her unwillingness to reply to that shot, he bowed and moved towards his own mount.

Lady Wroxeter had not been able to hear their conversation, but, feeling instinctively that Philippa had insulted their escort, she turned in the saddle and gave her daughter a warning look.

They travelled for the rest of the day without incident and arrived at dusk at an inn on the outskirts of Carmarthen. Sir Rhys had chosen one less fashionable but apparently clean and respectable. He arranged for a private chamber for the ladies, informing the landlord’s wife that Lady Wroxeter was a cousin of his, who was travelling with her daughter and brother to visit a sick relative who lived in the Marches. He, himself, he said cheerily, would make do with the common chamber and, as Peter Fairley announced his intention of sleeping with their horses in the stable, he ordered David, his squire, to join him there.

After a hearty meal the ladies retired and assisted each other to undress.

“Philippa,” Lady Wroxeter said, wrinkling her brow in concern, “you have not quarrelled with Sir Rhys, have you? I asked you to have a care. I thought there seemed something of an atmosphere between you after our stop for dinner. We are in enough danger as it is. Do not antagonise the man.”

Philippa shrugged irritably. “I merely made it clear to him when he passed an opinion on our state of dress that our straitened circumstances are due in part to his enrichment at our expense.”

“But that is hardly true. King Henry would have granted your father’s lands to, if not Sir Rhys’s father, then another one of his supporters after your father became a proscribed traitor.”

“But Sir Rhys’s father turned traitor to his rightful king at Redmoor,” Philippa snapped.

“I doubt if Sir Rhys was quite old enough to fight for the Tudor either at Redmoor or Stoke and can hardly be blamed for what his father did,” Cressida reminded her. “In all events, those battles were over long ago and we have your future to consider now.”

“You wish that my father was not so concerned with the Duchess Margaret’s machinations?” Philippa posed, somewhat shocked by such a suggestion.

“Like most women, I wish your father would sometimes consider the cost of his outdated allegiance and think a little more of us,” Cressida rejoined tartly. “I love your father with my whole heart and will remain loyal to him whatever he chooses to do, but I do have you to think about.”

Wearily she climbed into bed and Philippa thought it best to say nothing further.

She lay wakeful. Her fears had been thoroughly aroused in Pembroke and would not be put to rest. Her mother had not been present during that dreadful journey to the coast, four years ago, when she had been forced to flee from England with her friends, the Allards. The King’s body squire, John Hilyard, had followed them and attempted to take Philippa prisoner, to hold her hostage for her father’s compliance to King Henry’s will. It had been a hard fight when he had overtaken them and Philippa had been little more than a child then, but she had known real heartstopping fear that they would be killed. John Hilyard had paid the price and lost his life as a consequence of that encounter and his body had been thrown over a hedge. In retrospect she recalled how they had all set their teeth and struggled on, their friend, Sir Adam Westlake, severely wounded in the fight and Richard Allard still suffering from the effects of the torture he had endured as King Henry’s prisoner in the Tower of London. Report of Hilyard’s death must have reached the King. Philippa doubted if she would ever be forgiven. If she could be captured now, on this visit, how great a prize she and her mother would be if Rhys Griffith decided to hand them over. Somehow she must convince her mother of their danger and try to escape from Rhys’s clutches.

Cressida had fallen into an exhausted slumber at her side. Cautiously Philippa climbed from the bed and pulled her gown over her head, but was forced to leave it unlaced at the back. She thought it most likely that, despite his avowed intention of staying with the horses, Peter had more than probably stolen back to sleep nearer to his charges. She must seek him out and confer with him about their next move.

She looked back to see if her mother had wakened but Cressida stirred, then turned over and went back to sleep again. Philippa gave a little sigh of relief, stole to the door and carefully undid the latch. She had not dared to light a candle and found herself in total darkness on the landing when the door opened. The crack in the shutter had lightened her chamber sufficiently well for to see there, but now the blackness appeared absolute and she hesitated for moments to allow her eyes to adjust. After a second or two she could begin to see dimly in greyness and was about to step forward when she stumbled against something soft and yielding right before her feet.

“Peter,” she called softly but, before she could bend to examine the sleeping form further, her ankles were caught in a tight hold and she fell backwards into the arms of the man who had risen, cat-like, into a crouch at her advance. A hand fastened cruelly over her mouth and almost cut off her breath.

A harsh whisper came from the darkness. “God’s Wounds, mistress, what are you about? Not again! Did your previous hazardous encounter teach you nothing?”

She struggled ineffectively in her captor’s arms, realising, in fury, that she had been caught by the very man she had wished to avoid.

“If I remove my hand, will you cry out and waken everyone in the inn?” he demanded softly. “If not, shake your head and I will oblige.”

She shook her head vigorously and he released the gagging hand so that she could draw in ragged gasps of breath again. Her knees felt weak—she feared they would let her down and leaned against the door for support. He had risen to his feet fully now and was still holding her by one shoulder, then he urged her silently but imperiously down the stairs where he pushed open the door of the tap room in front of her and thrust her inside.

“We can talk more privately in here.”

She made to argue hotly but he lifted a hand impatiently to prevent her, and stood facing her, hands on his hips.

“Now, mistress, I demand to know what business brings you from your chamber half undressed.” His eyes passed insolently over her body on which her gown hung loosely and one shoulder was bared to his hard gaze. “I take it that your mother is unaware of this escapade? What are you doing, Lady Philippa? Are you in search of Master Fairley?”

She was about to agree that she was until she understood by the hard gleam in his eyes that he thought her reason for doing so was quite unacceptable. Her cheeks flamed and she went hot with embarrassment and anger that he might have so little regard for her sense of propriety.

“How dare you question me!” she snapped impatiently and turned to hasten towards the door again in order to make her escape, but he caught her by the arm again and pulled her towards him roughly.

“I have every reason to do so since I have made myself responsible for your safety.”

“No one asked you to,” she flared back.

The room was, of course, deserted and she was aware that her voice had risen and that she might well have awakened someone upstairs who might come to discover what was causing a disturbance in the night. The room seemed chilly and she turned towards the fire where the embers had been banked down but a residual warmth was still being given out. Despite the day’s summer warmth, it had been kindled to allow mulled ale and spiced wine to be produced for travellers and customers who requested it. She realised suddenly that she was quite alone with this man she regarded as an enemy and knew that her shivers were caused by something other than the chilliness of the summer night.

Tiredly she said, “Allow me, sir, to return to my chamber now. I am wearied.”

“Not too wearied to be wandering about. I will allow you to go, mistress, when you provide me with a suitable explanation for this wanton behaviour.”

“It does not concern you. I do not have to answer to you, sir.”

He did not favour that remark with an answer, but released her arm and stood dominatingly before her, feet apart, arms folded.

His very attitude and the fact that he had dispensed with the courtesy of affording her her proper title but had addressed her as “mistress”, rather than “my lady”, fired her to anger once more.

“If you must have an explanation, yes, I was, indeed, looking for Peter.”

“Why?”

The single word was uttered without any courteous preamble.

“As I have said, it is of no concern of yours. I—I—” She flailed about in her mind for an acceptable reason. She dared not give him the true one. “I—I simply wanted to talk with him—about the problems of the journey and—and did not wish to alarm my mother.”

“You are sure you have no other reason for not alarming your mother?” The question was disconcertingly blunt, so much so that she gasped aloud.

“Are you suggesting—?”

“I am suggesting nothing. The facts seem plain enough. You get up in the middle of the night, half undressed, in order to see your father’s squire. It requires little more speculation on my part.”

In sudden fury she lashed out at his cheek, but he caught her hand before it could do damage and held it in a punishing grip, so that she cried out in pain. “Little hell cat,” he murmured softly and deliberately.

She struggled to free herself. His grasp was delivering real pain and she knew there would be bruises to show for it in the morning. He released her at last and she stumbled backwards.

“How dare you!” she stuttered, very close to tears. “How dare you imply that Peter and I would—” Her breath ended in a splutter of unutterable rage. “Why, Peter, unlike you, is the soul of honour. He is totally devoted to our interests and discreet and my father trusts him with all our lives…”

“I do not doubt that, mistress,” he said grimly, “but can he trust him with his daughter’s honour? Last evening, as I recall, you were supposedly out looking for him then because you said he was late returning to you and you were worried about him.”

“That was the truth,” she retorted, sparks flying from her lovely blue-green eyes. “Perhaps you would like to question my concern for his welfare and put that down to a dishonourable reason. I imagine you are less concerned about the welfare of your own retainers.”

He was silent for a while, not rising to her taunt, watching the angry rise and fall of her breasts, the looseness of her unfastened gown more than normally revealing. Once more he marvelled at her loveliness, so exquisitely formed, like a faery sprite, more beautiful than he had remembered her mother to have been when she had captivated his boy’s heart so long ago. He felt an ungovernable anger. Philippa Telford might look like a child, but she most certainly was not. He had the evidence of that before his eyes. She was radiantly lovely, enough to seduce the whole of the male population within the Duchess Margaret’s court, he thought, yet she was here in search of her father’s squire, a man surely too old and unworthy to be her lover. Was he judging her too harshly? Was she really innocent at heart, simply anxious to talk with the man, as she had said, about the difficulties of the journey ahead? Unaccountably he found himself wanting to believe her. She was so young—sixteen, seventeen perhaps—and he believed her parents had kept her well chaperoned. Yet, the thought came to him that, beautiful as she was and well born, she had not concealed how poverty-stricken they were in exile in Burgundy. She must be fully aware of how difficult it was going to be for her father to provide her with a suitable husband. How galling that must be to her…

He sighed heavily. In her present mood he was going to find it hard to convince her that this rash behaviour was indiscreet, if not downright dangerous.

“Lady Philippa, you know, I am sure, that this is a difficult and dangerous time for your mother and you. It behoves you to be circumspect.” He lifted a hand imperiously as she made to interrupt him. “No, hear me out. I cannot imagine why you should wish to seek out your father’s squire at this hour of the night, but there must be no more of these escapades. Do you hear me?”

“I hear you,” she grated through clenched teeth. “I would like to know just why you were sleeping outside our door rather than in the common chamber where you said you would be.”

“I have already explained. I regard myself as your protector,” he returned mildly. “Though the wars are over, the times are still troubled. King’s men are everywhere and soldiers, off duty, can pose problems for vulnerable women. I am sure that I do not have to explain that to you.”

“Are you our protector or our jailer?” she said stonily and his eyes opened wide and darkened to obsidian.

Hastily she added, somewhat lamely, “I meant that—I do not understand why you should appoint yourself our guardian.”

He shrugged. “Perhaps because Fate or the Virgin cast you both before me as being in need. Is that not a good enough reason, mistress?”

Haughtily she shook her glorious hair, which lay unbound in heavy red-gold waves upon her shoulders. He felt an irresistible desire to pull her towards him and run his fingers through it. What was she doing, he thought savagely, appearing before a man in the night like that? Had she no sense of decorum? Didn’t she realise what temptations she could arouse in men? He took himself firmly in hand. She was young, vulnerable, and under his protection. He must hold himself in check.

“I am not sure,” she said icily, “whether either my mother or I are gladdened that fate decided to take such a hand in our affairs. Now, sir, will you please stand aside and allow me to return to my mother?”

He nodded slowly and stepped aside from the door so that she might move towards it unhindered. He could not allow himself to touch her, not again.

He said a trifle hoarsely, “Certainly, Lady Philippa, but be assured that I shall resume my post outside your door the moment you are settled inside.”

She did not deign to reply, but sulkily moved past him and mounted the stairs back to their chamber.

He followed and settled himself, seated with his back to their door. He was bewitched as if she had thrown faery dust before his eyes and taken possession of his very soul. How could this have happened to him and so suddenly? Not only was she so beautiful that just to look at her caused an ache within his loins, but she had spirit and courage. He could only pray that those very virtues he admired in her did not bring her into further dangers.

He pondered upon her reaction to his unvoiced accusation that she was wandering out to meet her lover. She had rejected it out of hand and with considerable indignation. Could he believe her? Would she not, if caught out like that, react in exactly that way? And had he any right to be angered by her behaviour?

He allowed himself a little secret smile. Certainly she had made no bones about admitting the fact that she despised him. Why? Simply because he was in possession of her father’s former lands? Had she expected to arrive in England and find those estates and manor houses empty and neglected? Was it not usual for the victor in any combat to hand out spoils to his supporters? At Duchess Margaret’s court, intrigue-ridden as it was, she could not be unaware of those situations.

He had recognised Lady Wroxeter on sight and on impulse offered her his protection on this journey. He knew of the distress of her parents at being so long parted from their daughter by circumstances they were powerless to alter and of the present serious illness of Sir Daniel. It had seemed reasonable and his duty to assume responsibility for the safety of his neighbour’s kin. He had not expected such a hostile reaction from Lady Philippa. He sighed. They would be thrown together for several more days. In honour he must control his growing feelings for her. He had gravely insulted her by his suggestion that she had acted wantonly. There would be time for him to discover if he were, in fact, mistaken and, if so, to attempt to repair the damage.

The darkness upon the landing was beginning to lighten to grey. He settled himself more comfortably, yet in a position to continue his nocturnal watch.

Philippa stole back to her bed, careful not to disturb her sleeping mother. Her cheeks were still hot with embarrassed fury directed at the man who was separated from her only by the thickness of the chamber door. Her plan would have to be abandoned. Rhys Griffith would not move from his post this night. She would have to try to find some other opportunity to have talk with Peter away from the man’s insufferable vigilance.

She punched the straw-filled pillow violently to relieve her feelings and wriggled down in the bed. Yet sleep evaded her. The vision of the man’s dark presence continued to dominate her thoughts. She tossed and turned restlessly. She had never before encountered a man so bluntly and insultingly spoken. No one in the Duchess’s retinue, nor even any nobleman at Queen Elizabeth’s court at Westminster, would have dared to question her so accusingly. He was hateful and she had no way of proving to him how shamefully wrong he was in his suspicions. Peter was a dear and trusted friend whom she had known from childhood. Never could she think of him as—she blushed inwardly at the thought—as a lover. Even if they had had more intimate feelings towards each other, neither would have behaved so indecorously. Peter would have regarded such desires as a blot upon the knightly honour to which he had once aspired. Knowing how vulnerable her position was at court, she had been particularly careful that she was never alone in any man’s company, since her dowerless state would have made it impossible for any man to offer her honourable marriage.

Rhys Griffith had immediately jumped to the wrong conclusion. Indignantly she asked herself what business it was of his? He had no hold over her. It was as if he were—jealous! The idea was laughable.

Once more she pounded her pillow in impotent fury. Somehow she must convince him that he had accused her falsely, but without alerting him to the true reason for her determination to meet with Peter privately for that could put them all in danger. Strangely she was most anxious that Rhys Griffith should not think ill of her, though, for the life of her, she could not understand her own reason for caring.

Chapter Three

They travelled by easy stages through the lovely Welsh countryside, through Carmarthen, Landovery and Buith Wells, and stayed at last at an inn in Leominster. The weather stayed fine. The rain, which had fallen before their arrival in Wales, had laid the dust and the roads were reasonably comfortable as a result, neither too miry or too dusty and hard ridged.

As on the stops they had made previously, the inn Sir Rhys had chosen was comfortable and clean without being luxurious or fashionable. Philippa had had no opportunity to speak with Peter Fairley privately during the journey. Though they had ridden side by side, she was conscious that Sir Rhys, riding with her mother only some yards ahead of her, could hear anything they had to say and, therefore, she had had to talk of everyday things, the comforts or disadvantages of the inns they stayed at, the beauty of the scenery, or the weather. At all times, whether he was looking at them or not, Philippa was aware that she and Peter were under close scrutiny and it irked her.

At Leominster she had an excuse at last to follow Peter down to the stables, hoping to find him alone. Her little Welsh cob, of whom she had grown very fond, was limping just a little by the time they arrived and she expressed a desire to go and ask Peter to discover, if he could, the reason and pronounce his opinion on whether she were well enough to proceed next day. Sir Rhys was absent from the eating room for the moment and Philippa’s mother nodded her agreement.

Philippa was fortunate to find Peter alone and he was, as she entered the stable, examining the cob’s right fore hoof.

He looked up, smiling, as he saw Philippa. “She has gathered a small stone. It isn’t serious. I’m removing it now.”

“Will she be able to carry me tomorrow? I don’t want to further lame her.”

“Yes, my lady, she will be fine when she’s rested.”

Philippa approached him and looked back to see that no one was near the opened doorway.

“I’ve been anxious to speak with you alone since we left Milford Haven.”

He nodded. “It has proved difficult. I would have preferred to have closer access to your mother, also, but it seemed unwise.”

“Peter, do you think we are in danger from this man?”

“Sir Rhys? I doubt it, though he is the King’s man. Had he any intention of betraying us he would have done so before now.”