Полная версия

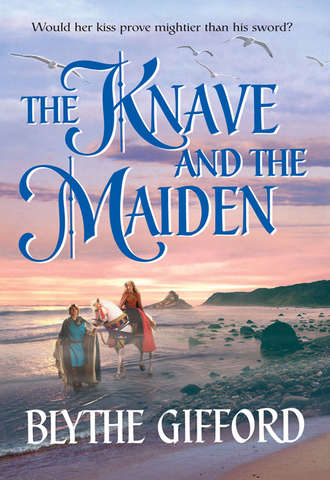

The Knave and the Maiden

He looked back at the girl, digging up the weeds. He was no knight from a romance, but he had a way with women. Camp followers across France could attest to that. Every woman had a sweet spot if you took time to look. Where would this one’s be? Her shell-like ears? The curve of her neck?

She stood and turned, smiling at him briefly and the purest blue eyes he had ever seen looked into his wretched soul. He felt as transparent as stained glass.

And for a moment, he shook with fear he had never felt before a battle with the French.

He shrugged off the feeling. There was no reason for it. She was not that remarkable. Tall. Rounded breasts. Freckles. A broad brow. Her mouth, the top lip serious, the bottom one with a sensual curve. And an overall air as if she were not quite of this earth.

She turned away and kneeled to weed the next row.

“Why?” He had asked God that question regularly without reply. He didn’t know why he expected a country Prioress to answer.

The Prioress, broad of chest and hip, did not take the question theologically. Her dangling crucifix clanked like a sword as she strode away from the window, out of hearing of the happy hum. “You think me cruel.”

“I have seen war, Mother Julian. Man’s inhumanity is no worse than God’s.” He had a sudden thought. The usual resolution to a tumble with a maid would find him married in a fortnight. “If it is a husband you need, I’m not the one. I cannot support a wife.”

I can barely support myself.

“You will not be asked to marry the girl.”

He eyed a neatly stitched patch on her faded black habit and wondered whether she had the money she promised. “Nor fined.”

“If you had any money you would not be considering my offer. No, not fined, either. God has a different plan.”

God again. The excuse for most of the ill done in the world. Hypocrites like this one had driven him from the Church. “If you do not care for my immortal soul, aren’t you concerned about hers? What will happen to her? Afterward?”

Her eyes flickered over him, as if trying to decide whether he was worthy of an answer. “Her life will go on much as before.”

He doubted that. But the money she offered would be enough for him to give William the gift of the pilgrimage. Enough and more. William would be dead soon. Garren would have no welcome under Richard’s reign. All he owned was his horse and his armor. With England and France at peace, he had no place to go.

With what she offered, and the few coins he had left from France, he might find a corner of England no one else wanted, where he and God could ignore each other.

“Can you pay me now?”

“I’m a Prioress, not a fool. You’ll get your money when you return. If you succeed. Now, will you do it?”

The girl’s happy hum still buzzed in his ear. What was one more sin to a God who punished only the righteous? Besides, the Church didn’t need this one. The Church had already taken enough.

He nodded.

“Sister Marian also goes to the shrine. She knows nothing of this. She wants the girl to fulfill her vow and return to the order.”

“And you do not.”

The Prioress crossed herself. A faint shudder ruffled the edge of her robe. “She is a foundling with the Devil’s own eyes. He can have her back.” Her smile was anything but holy. “And you will be His instrument.”

Chapter Two

“Look. There he is. The Savior.” Sister Marian’s words tickled Dominica’s ear. She whispered so no one would overhear the blasphemous nickname for the man who, like the true Savior, had raised a man from the dead.

“Where? Which one?” Dominica did not bother to whisper. The entire household had gathered in the Readington Castle courtyard to witness the blessing of God’s simple pilgrims before they left on their journey. The sounds of braying asses, snorting horses and barking dogs assaulted her ears, accustomed to convent quiet. At Sister’s feet, Innocent barked fiercely at every one of God’s four-legged creatures.

“Over there. By the big bay horse.”

She gasped. He was the man she had seen through the Prioress’s window.

He certainly did not look holy. His broad shoulders looked made to stand against the real world, not the spirit one. Dark brown curls, the color of well-worn leather, fought their way around his head and onto his cheeks, where he had begun to grow a pilgrim’s beard. His skin had lived with sun and wind.

Then he met her eyes again. Just like the first time, something called to her, as strongly as if he had spoken. Surely this must be holiness.

With an unholy bark, Innocent dashed across the courtyard, chasing a large, orange cat.

“I’ll get him,” Dominica called, too late for Sister to object. It was going to be difficult to keep Innocent safe among the temptations of the world.

Her first running steps tangled in her skirts, so she swooped them out of the way. Fresh air swirled between her legs. Laughing, she scampered around two asses, finally scooping Innocent up at the feet of a horse.

A large bay horse. With a broad-shouldered man beside it.

The Savior was taller than he looked from a distance. A soldier’s sword hung next to his pilgrim’s bowl and bag. Something hung around his neck hid beneath his tunic, not for the world to see. A private penance, perhaps.

“Good morning,” she said, bending back her neck to meet his brown, no, green eyes. “I am Dominica.”

He looked at her squarely, eyes wary and sad, as if God had given him many trials to make him worthy. “I know who you are.”

At his glance, her blood bubbled through her fingers and around her stomach in an oddly pleasant way. “Did God tell you?” If God spoke to her, He must certainly have lengthy conversations with one so holy.

He scowled. Or repressed a smile. “The Prioress told me.”

She wondered what else the Prioress had told him. The dog wriggled in her arms. She scratched his head. “This is Innocent.”

The smile broke through. “Named in honor of our Holy Father in Avignon, no doubt.”

That, she was sure, the Prioress had not told him. Dominica raced on, not giving him time to wonder whether the name honored the Pope or mocked him. “We are all grateful to you for bringing the Earl back from the dead,” she said. “Did he stinketh like Lazarus?”

“Pardon?”

“The Bible says ‘Lazarus did stinketh because he hath been dead four days.’

The corner of his mouth twitched. “You did not hear about Lazarus’s stench in one of the Abbot’s homilies.”

Best not to tell him she had read it herself. “At the noon meal, the Sisters read the Scriptures and let me listen.” She waited for a sign of anger. Could one so touched by God discern her small deception?

“The story of Lazarus hardly sounds appetizing,” he said. “But, yes, we both did stinketh by the time we got home.”

“Of course, the Earl had not been dead for four days when you brought him back to life.”

The amusement leaked away and his green eyes darkened to brown. “I did not bring him back from the dead. I simply would not let him die.”

Dominica thought this a very fine theological distinction. “But you had faith in God’s power. ‘He that believeth in me though he were dead, yet shall he live.’”

“Be careful who you believe in. Faith can be dangerous.”

His words, bleak as his eyes, seemed as simple and as complex as scripture. She remembered the end of the Lazarus story. It was after the Pharisees learned what Jesus had done that they decided he must die.

“You know my name, but I do not know yours, Sir…?”

“Garren.”

“Sir Garren of what?”

“Sir Garren of nowhere. Sir Garren with nothing.” He bowed. “As befits a simple pilgrim.”

“Have you no home?”

He stroked the horse’s neck. “I have Roucoud de Readington.”

“Readington?”

“A gift from the Earl.” He frowned.

Why would he frown at such a wonderful gift? Readington must value him highly to give him such a magnificent animal. “And you are at home on a horse?”

“I have been a mercenary, paid to fight.”

“And now?”

“And now a palmer,” he muttered, “paid for this pilgrimage.”

Dominica was not surprised to have a palmer on the journey. She was surprised that it was The Savior. “What poor dead soul left twenty sous in his will for a pilgrimage for his soul?”

“Not a dead one—yet.”

He must mean the Earl of Readington himself, she thought, relieved. The secret was in good hands, if she would only stop asking questions. “Forgive me,” she said. “Keep the secret of your holy journey in your heart.”

“I am no holy man.”

Her question seemed to irritate him. How could he deny he was touched by God? They all knew the story. Today he journeyed to the Blessed Larina’s shrine. By Michaelmas, Dominica thought, he was likely to have a shrine of his own. “God selected you as His instrument to save the Earl’s life.”

He searched her eyes for a long, silent moment. “An instrument can serve many hands. God and the Devil both make use of fire.”

She shivered.

The bell tolled and like a flock of geese, the gray cloaked pilgrims fluttered toward the chapel door. She put Innocent down and he trotted back to Sister Marian, tail straight up. Dominica tried to follow, but her legs refused to walk away.

“Please,” she whispered, “give me your blessing.”

He shrugged into his gray scleverin as if the cloak were chain mail. “Get your blessing from the Abbot with the rest of the pilgrims.”

“But you are The Sav—” She bit her tongue. “You are special.”

His eyes blazed, their mood as changeable as their color, and she felt a hint of the danger faith might bring.

“I told you,” he said, “I am nothing holy. I can give you none of God’s blessing.”

“Please.” She grabbed his large, square hands with trembling fingers. Kneeling in the dirt before him, she touched her lips to the fine dark hairs on his knuckles.

He snatched his hands away.

She grabbed them back, put his hands on her bowed head and pressed her palms over them, desperate to hold them there.

His palm stiffened. Then, slowly, his hand cupped the curve of her head and slid down to the bare skin at the back of her neck. His fingers seared her like a brand. Her chest tightened and she tried to breathe. The smell of the courtyard dust mingled with a new scent, rich and rounded. One that came from him.

The braying church bell faded, but the sense of peace she had expected did not come. Her heart beat in her ears, as if all four humours in her body were wildly out of balance.

He jerked away, waving his hand in a gesture that could have been benediction, dismissal or disgust.

“Thank you, Sir Garren of the Here and Now,” she whispered, running back to the safety of Sister and Innocent, afraid to look at him again, afraid she had already put too much of herself in his hands.

Garren’s palms burned as if he had touched fire.

God’s holy blood. She thinks I’m a saint.

He laughed at the blasphemy of it.

His body’s stiff response was a man’s, but the fall of the pilgrim’s cloak disguised that along with all his other sins.

This job would be too easy. Too pleasant. His hands ached to touch her soft curves, but he winced at taking advantage of the burning faith in her eyes. She thought him touched by God somehow. What a disappointment it would be to discover how much of a man he was.

He shook off the guilt. She had to learn eventually, just as he had. Faith was a trap for fools.

Garren turned to see the Prioress, standing before the chapel door, smiling as if she had seen the entire scene. As if she wanted to see him take the girl here in the dust of the courtyard.

The girl, with her wide-eyed faith, was no match for the Prioress. The thought angered him. Maybe he could even the odds. Maybe he would cheat the Church. Tell the Prioress he had taken the girl and take the Church’s money for a sin he did not commit. Naturally, the girl would say she remained pure, but she would be damaged just as if he had taken her. But free. She would be free from the clutches of the Church.

Smiling, Garren patted Roucoud, handed the horse’s reins to a waiting page, then joined the other pilgrims. Maids, knights, squires, cooks, pages, even the Prioress and Richard stood respectfully aside as they walked across the courtyard to the chapel. He hoped William could not see from his window as Richard usurped the rightful place of the Earl of Readington.

Aware of his fellow travelers for the first time, Garren counted the group as they walked through the church door. There were less than a dozen. A young couple holding hands. A scar-faced man with an off-center nose. A plump woman, a merchant’s wife by the weave of her cloak. Two men, brothers by the cut of their chins. A few others.

Each was adorned with a cross, either sewn into the long, gray cloak or, for the merchant’s wife, hung around her neck.

Dominica, a head taller than the little nun beside her, walked with those sea-blue eyes focused on God, ignoring the wiggling dog in her arms. The dog’s left ear flopped in time to his wagging tail, but the right one was missing, bitten off, no doubt, by a cornered fox. At the church door, she put him down and turned back three times to make him stay. Garren grinned. The dog, as least, was not reverent.

As Dominica passed into the shadow of the chapel, Richard laid his hand on her shoulder and whispered in her ear. She pulled away, hurrying ahead without even glancing at him.

Garren clenched his fist, then deliberately stretched his fingers. He needed no more reasons to hate Richard.

Richard and the Prioress turned to Garren, the only pilgrim still in the courtyard. A breathless household stood aside, lining a path for him to enter the Readington chapel.

The wooden doors seemed miles away.

He trudged past them on leaden feet, eyes on the stone peak above the door, trying to ignore their stares and whispers. His cape with its cross, stitched on at William’s insistence, the relic case around his neck, all seemed a costume borrowed from a miracle player. William’s mysterious message lay coiled against his chest.

Only his sword and the shell around his neck felt familiar. The lead shell clanking against the reliquary was a souvenir of the family snatched away by a God who had not saved them, even though they had paid His price.

“Come, Garren.” Richard never honored him with Sir. “God and the Abbot await.”

Dust motes chased themselves in the stream of late morning sun that stopped short of the altar. Garren knelt next to Dominica at the altar rail. Her eyes on the Abbot, she spared him no more of a glance than she had Richard.

The Abbot, who had traveled all the way from White Wood to give the blessing, intoned in Latin, designed to make him sound closer to God’s deaf ears than the rest of us, Garren thought.

The girl moved her lips with his words, almost as if she understood them. Her hair shimmered around her head like a halo. She was young and vulnerable and untouched by the world and he had the strangest sensation that despite it all, she was stronger than he. He suddenly wondered whether he could touch her and remain the same person.

The Abbot switched to the common tongue. “Those who have gathered to go on pilgrimage, are you ready for this journey? Have you set aside worldly goods to travel simply, as did Our Lord?”

Garren watched Dominica nod, wondering what worldly goods she owned. He had few enough. In nine years, he had amassed no more than he could carry.

“When you reach the shrine, you must make sincere confession or your journey will not find favor in the sight of God and the saints. Will you all make your confessions?”

Murmured yeses rustled like dry leaves. Garren held his tongue. He would confess to God when God returned the favor.

“And particularly Lord Richard asks that each of you pray for his beloved brother, the Earl of Readington, who was saved from death only to live in a state too near to heaven and too far from earth.”

A faint, forceful voice, William’s own, interrupted. “I thank my brother, but I shall ask for my own salvation.”

“What the—?” Richard sputtered.

Garren half rose, wanting to believe in miracles, wanting to see William standing tall and strong again. Shielding his eyes against the sun, Garren turned toward the church door. A reclining figure, almost too tall for the litter, lay silhouetted against the sunlight. William, pale and thin as a wraith, was carried on his pallet by two footmen, one holding a pewter pan in case of need.

The crowd inhaled with a single breath. Then, hands fluttered from foreheads to shoulders, making the sign of the cross against a spirit raised from the dead.

William waved his two servants forward. The crowd parted as he was carried to the altar rail, where the Prioress bent over him. Richard, with petulant lips and pitiless eyes, stood erect.

The Abbot, flustered, rolled his eyes to Heaven for guidance. There was no ceremony for this occasion. “Already God has given the Earl strength from your pure intentions.” His voice swelled. “You who take this journey, pray for a miracle!”

William lifted a hand. “Thank you for…prayers.”

Garren’s heart twisted at the sound of William’s voice. Once so strong in battle, it quavered as one twice his age.

“I have ordered,” he continued, “first day’s food for all.”

“A magnificent gesture, my Lord Readington,” the Abbot said.

Richard scowled.

William waved his hand as if brushing away a wisp of smoke. “And let it be known,” he stopped for a breath. “Garren walks for me and carries my petition to the Blessed Larina.”

William grabbed his stomach and turned, retching, just in time to hit the pewter pan. Garren closed his eyes, as if William’s pain would not exist if he did not see it. As if he could close his eyes and bring back the past.

“Let us end with a prayer for Sir Garren’s success and Lord Readington’s recovery before I bless the staffs and distribute the testimoniales,” the Abbot said, quickly.

Garren walks for me, William had said. What would they think of him now?

Dominica smiled at him, but the rest looked awestruck, as if they really saw a man of God.

Everyone except the Prioress. And Richard.

Chapter Three

Dominica pressed her forehead against the altar rail, trying to concentrate on God instead of the Earl’s sudden appearance. Completing the ceremony, the Abbot kissed her staff and placed it, solid and balanced, in her outstretched hands. She pressed her lips against the raw wood, stripped of bark, then set it in front of her.

Next, the Abbot handed her the testimoniales, the scroll with the Bishop’s magic words that made her truly a pilgrim. Her fingers tingled as she slipped it into her bag, next to her own parchment and quill. Later, when no one could see, she would compare the copyist’s letters with her own.

Bowing her head into her hands, she searched for the voice of God inside her, trying to ignore The Savior on her left. She wondered if he was watching her. He was as solid as the staff in her hands. The kind of man you could lean on. She studied him through her fingers. Clutching his staff like a weapon, he looked like a man used to standing alone, not leaning on a staff. Nor a friend. Nor even God.

Squeezing her eyes shut, she brought her mind back to the reason for her journey.

Please God, give me a sign at the shrine that I am to keep my home in your service and help spread your word.

She wanted to add “in the common tongue,” but decided not to force that point with God just yet.

She opened her eyes and peeked through her fingers past Sister Marian on her right. A servant daubed sweat from the Earl’s forehead. God had spared him nearly ten years ago at the height of the Death and taken his father instead. She still remembered weeks of mourning when the old Earl died. Sister Marian’s eyes had been red for days. But God had spared the son. Surely God had sent The Savior to protect him again.

She added a prayer for the Earl who surely deserved God’s help. And hers.

The Abbot spoke his last amen and her fellow pilgrims rose, leaning on their staffs, and filed past the Earl on their way out of the chapel, giving thanks for his gift of food.

When Sister Marian stopped before him, he thanked her for her work on the Readington psalter, clutched in his white-spotted hand.

Sister brushed the thin, blond hair from his damp brow as if he were a child. Many were afraid to touch him now. They whispered “leprosy” when they saw the mottled black-and-pink-and-white spots on his skin.

Dominica quaked a little, too, when it was her turn to bend her knees before him. But he had been so nice to her as a child. Not like Richard.

He lifted a finger to his lips. “Remember. A secret.”

She pursed her lips, nodding, and looked for Lord Richard, still talking with Mother Julian and Abbot. Make sincere confession, the Abbot had said. Did keeping a secret require the same penance as a lie? She thought not. A lie had words. Words made it real.

As she moved on, The Savior knelt beside the Earl, clasping the dying man’s shoulder in a gesture that might have been called tender. Sir Garren will hurry, she thought, relieved. We’ll be there in time for The Blessed Larina to save him.

With Sister, Dominica circled back to the altar rail, kneeling for a final blessing from the Prioress. She wanted words that would keep her company until she was safe at home again. But instead of a kiss of peace, the Prioress hissed at her, too softly for anyone else to hear. “Remember, any hint of trouble and you will have no home with us.” Then, she turned her back, murmuring to Sister Marian in Latin.

Dominica gripped her staff. A knot in the wood scraped her palm. No home at the Priory meant she had no home at all.

Her own blessing complete, Sister Marian leaned on her staff and straightened her reluctant knees. She was not more than two score years, but copying had made her body old and chanting had kept her voice young.

Dominica, still shaking from Mother Julian’s words, offered her arm. Together, she and Sister shared slow steps toward the chapel door. Cool tears blurred her fellow pilgrims into a lumpy, gray cloud in the middle of the sunny courtyard. Surely God would not let the Prioress stand in the way of His plan for her life.

As they paused in the doorway, she swiped the one tear that escaped.

“What is the matter, child?” Sister patted Dominica’s arm with stiff fingers. “Why do you cry? Have you changed your mind? Do you want to stay here?”

More than anything, she thought, forcing a smile. No reason to disturb Sister Marian with words not meant for her. She shook her head and wiped the back of her hand against the scratchy wool. “Of course I want to stay here. That’s why I am going away, so I need never leave again.”

“Outside the Priory, the world is large. Many things can happen.”

“And I plan to write about them so I can remember when I return.” She patted the sack where her precious parchment and quill lay.

“You say that now.” Weary sadness shadowed Sister’s eyes. “Perhaps you will not want to come back.”

“Of course I will.” Even the thought of being abandoned to the world made her long for the comfort of the Priory. “I know every brick in the chapel, every branch on the tree in the garden. It is where I belong.”

Sister Marian blinked as they stepped into the sunshine. She reached up, squaring the scleverin on Dominica’s shoulders. Sister Barbara had stitched the rough gray wool cloak in loving haste, since Dominica’s fingers were better at copying than stitching and Sister Marian said the cloak she wore on pilgrimage five years ago was still perfectly fine and she did not need another.

“Have you ever missed having a mother, Neeca?”